Competing and Conflicting Power Dynamics in Waqfs in Kenya, 1900-2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women and Islamic Law Christie S

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty and Deans 2008 Lifting the Veil: Women and Islamic Law Christie S. Warren William & Mary Law School, [email protected] Repository Citation Warren, Christie S., "Lifting the Veil: Women and Islamic Law" (2008). Faculty Publications. 99. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs/99 Copyright c 2008 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs LIFTING THE VEIL: WOMEN AND ISLAMIC LAW CHRISTIES. WARREN * "Treat your women well and be kind to them for they are your partners and committed helpers." From the Farewell Address of the Holy Prophet Muhammad1 I. INTRODUCTION By the end of February 632 and at the age of sixty-three, the Prophet Muhammad believed that his days on earth were coming to an end.2 He announced to his followers that he would lead the hajj, the annual pilgrimage to Mecca, himself that year.3 On March 3, the Prophet delivered his farewell sermon near Mount Arafat.4 Among the limited number of topics he chose to include in his last public speech, he encouraged his followers to deal justly with one another and treat women well. 5 In the modem era, the rights of women under Islamic law have come under heightened scrutiny. Some commentators find the Prophet's farewell speech to be inconsistent with the way women are treated in some areas of the Muslim world. In Saudi Arabia, for example, women may neither drive nor vote. -

Making Moral Worlds: Individual and Social Processes of Meaning-Making in a Somali Diaspora Anna Jacobsen Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) 1-1-2011 Making Moral Worlds: Individual and Social Processes of Meaning-Making in a Somali Diaspora Anna Jacobsen Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Recommended Citation Jacobsen, Anna, "Making Moral Worlds: Individual and Social Processes of Meaning-Making in a Somali Diaspora" (2011). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 592. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/592 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Anthropology Dissertation Examination Committee: John R. Bowen, chair Geoff Childs Carolyn Lesorogol Rebecca Lester Shanti Parikh Timothy Parsons Carolyn Sargent Making Moral Worlds: Individual and Social Processes of Meaning Making in a Somali Diaspora by Anna Lisa Jacobsen A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2011 Saint Louis, Missouri Abstract: I argue that most Somalis living in exile in the Eastleigh neighborhood of Nairobi, Kenya are deeply concerned with morality both as individually performed and proven, and as socially defined, authorized and constructed. In this dissertation, I explore various aspects of Somali morality as it is constructed, debated, and reinforced by individual women living in Eastleigh. -

Black-Thursday.Pdf

Published on Books on Islam and Muslims | Al-Islam.org (https://www.al-islam.org) Home > Black Thursday Black Thursday رزﻳﺔ ﻳﻮم اﻟﺨﻤﻴﺲ English Translation of Raziyyat Yawm al-Khamees Author(s): Muhammad al-Tijani al-Samawi [3] Publisher(s): Ansariyan Publications - Qum [4] The text authored by Muhammad Al Tijani Al Samawi presents an english translation of the famous event of Raziyyat Yawm al-Khamees, known as Black Thursday which took place in the last days before the Holy Prophet's demise. It concerns an incident during the Prophet's illness when he asked for writing materials to dictate a will, but the people present around him said that he was talking nonsense. This event is a point of controversy between the two largest sects of Islam. This book presents the reality of what happened and who was the person involved who had the audacity to cast such aspersion on the Messenger of Allah (S). Translator(s): Sayyid Maqsood Athar [5] Category: Sunni & Shi’a [6] Early Islamic History [7] Prophet Muhammad [8] Miscellaneous information: Editor: Sayyid Athar Husain S. H. Rizvi First Edition: 2009-1388-1430 ISBN: 978-964-219-089-8 Featured Category: Debates & discussions [9] Translator’s Foreword In the Name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful. Praise be to Allah, the Lord of the worlds and benedictions be upon Prophet Muhammad and his Purified Progeny. The Important role that translation plays in propagation of religion is known to all. Since most Islamic texts are in Arabic or Persian, it is only through translating them into English can we make them popular among the literate Muslim youth of today. -

Resources for the Study of Islamic Architecture Historical Section

RESOURCES FOR THE STUDY OF ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE HISTORICAL SECTION Prepared by: Sabri Jarrar András Riedlmayer Jeffrey B. Spurr © 1994 AGA KHAN PROGRAM FOR ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE RESOURCES FOR THE STUDY OF ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE HISTORICAL SECTION BIBLIOGRAPHIC COMPONENT Historical Section, Bibliographic Component Reference Books BASIC REFERENCE TOOLS FOR THE HISTORY OF ISLAMIC ART AND ARCHITECTURE This list covers bibliographies, periodical indexes and other basic research tools; also included is a selection of monographs and surveys of architecture, with an emphasis on recent and well-illustrated works published after 1980. For an annotated guide to the most important such works published prior to that date, see Terry Allen, Islamic Architecture: An Introductory Bibliography. Cambridge, Mass., 1979 (available in photocopy from the Aga Khan Program at Harvard). For more comprehensive listings, see Creswell's Bibliography and its supplements, as well as the following subject bibliographies. GENERAL BIBLIOGRAPHIES AND PERIODICAL INDEXES Creswell, K. A. C. A Bibliography of the Architecture, Arts, and Crafts of Islam to 1st Jan. 1960 Cairo, 1961; reprt. 1978. /the largest and most comprehensive compilation of books and articles on all aspects of Islamic art and architecture (except numismatics- for titles on Islamic coins and medals see: L.A. Mayer, Bibliography of Moslem Numismatics and the periodical Numismatic Literature). Intelligently organized; incl. detailed annotations, e.g. listing buildings and objects illustrated in each of the works cited. Supplements: [1st]: 1961-1972 (Cairo, 1973); [2nd]: 1972-1980, with omissions from previous years (Cairo, 1984)./ Islamic Architecture: An Introductory Bibliography, ed. Terry Allen. Cambridge, Mass., 1979. /a selective and intelligently organized general overview of the literature to that date, with detailed and often critical annotations./ Index Islamicus 1665-1905, ed. -

Making Music, Making Muslims. a Case Study of Islamic Hip Hop And

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto Making Music, Making Muslims: A Case Study of Islamic Hip Hop and the Discursive Construction of Muslim Identities on the Internet Master’s thesis Intercultural Encounters Master’s Programme Study of Religions Faculty of Arts Inka Rantakallio October 2011 CONTENTS GLOSSARY ............................................................................................................4 I INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................5 1. Muslim hip hop as a reflection of globalization................................................5 1.1 Previous research ...................................................................................8 1.2 Research questions and the structure of the thesis.................................9 II MATERIAL, THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK AND METHOD ......................11 2. Research material ............................................................................................11 2.1 Description of research material ..........................................................11 2.2 Reflections on the research process and material ...............................14 3. Identity as a theoretical framework .................................................................16 3.1 The concept of identity........................................................................16 3.2 Religious communities, the Internet and music -

Abbreviations and Acronyms

PART II] THE GAZETTE OF PAKISTAN, EXTRA., JULY 23, 2019 1505(1) ISLAMABAD, TUESDAY, JULY 23, 2019 PART II Statutory Notifications (S. R. O.) GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTAN REVENUE DIVISION (Federal Board of Revenue) NOTIFICATIONS Islamabad, the 23rd July, 2019 (INCOME TAX) S.R.O. 829(I)/2019.—In exercise of the powers conferred by sub- section (4) of section 68 of the Income Tax Ordinance, 2001 (XLIX of 2001) and in supersession of its Notification No. S.R.O. 111(I)/2019 dated the lst February, 2019, the Federal Board of Revenue is pleased to notify the value of immoveable properties in columns (3) and (4) of the Table below in respect of areas of Abbottabad classified in column (2) thereof. (2) This notification shall come into force with effect from 24th July, 2019. 1505 (1—211) Price: Rs. 320.00 [1143(2019)/Ex.Gaz.] 1505(2) THE GAZETTE OF PAKISTAN, EXTRA., JULY 23, 2019 [PART II ABBOTTABAD Value of Commercial Value of Residential S.No. Areas property per marla property per marla (in Rs.) (in Rs.) (1) (2) (3) (4) 1 Main Bazar, Sadar Bazar, Jinnah Road, Masjid Bazar, 2,580,600 910,800 Sarafa Bazar Gardawara Gali Kutchery Road, Shop and Market. 2 Abbottabad Bazar 2,580,600 759,000 3 Iqbal Road 1,214,400 531,300 4 Mansehra Road 1,973,400 531,300 5 Jinnah Abad 2,277,000 1,062,600 6 Habibullah Colony - 1,062,600 7 Kaghan Colony 759,000 455,400 S.R.O. 830(I)/2019.—In exercise of the powers conferred by sub-section (4) of section 68 of the Income Tax Ordinance, 2001 (XLIX of 2001) and in supersession of its Notification No. -

Paradise Under Your Feet

اَل َجنَّ ۃ تَ ْح َت اَ ْق َدا م اﻻ َّم َھا ت Paradise Under Your Feet Mother’s Handbook Paradise Under Your Feet First published in USA in September 2016 By: Lajna Ima’illah, USA (ISBN: 978-1-882494-06-4) Publisher: Lajna Ima’illah, USA 15000 Good Hope Rd Silver Spring, MD 20905-4120 Revised Edition Published in UK 2019 By: Lajna Section Markazia 22 Deer Park Road, SW19 3TL London Printed in the UK at: Raqeem Press, Farnham © Islam International Publications Ltd. No part of this book may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, copying or information storage and retrieval systems without permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-1-84880-324-4 Paradise Under Your Feet Page intentionally left blank Page intentionally left blank Copyright © 2016, Lajna Ima’illah, USA All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. All inquiries and requests for information should be sent to [email protected]. The Lajna Ima’illah (Assembly of the Maidservants of God) is an international Muslim women’s organization, established by Hazrat Khalifatul Masih II (ra), the second successor to the Promised Messiah (as), as a vital branch of the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community. The Lajna Ima’illah’s objectives are to serve the spiritual and intellectual development of Ahmadi Muslim women, to enable them to raise their children in the practice of Islam and to serve humanity through beneficial programs. -

Islam, Ritual and the Ethical Life

ISLAM, RITUAL AND THE ETHICAL LIFE DAWAT IN THE TABLIGHI JAMAAT IN PAKISTAN Arsalan Khalid Khan Charlottesville, Virginia M.A. Anthropology, University of Virginia 2011 B.A. International Relations, Beloit College 2005 A Dissertation Presented to The Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology December, 2014 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 4 2. Islam and the Colonial Configuration of Religion 46 3. Ritual Ideology: Dawat, Personhood, Purity 74 4. Piety as Ethical Relatedness 110 5. From Precarious to Certain Faith: The Making of a Spiritual Home 156 6. Dawat and Transcendence in an Islamic Nation 195 7. Conclusion: Dawat as Islamic Modernity 240 1 Acknowledgements The research for this dissertation was funded by the Wenner-Gren Foundation, The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences at the University of Virginia, and the Department of Anthropology at the University of Virginia. The faculty in the Department of Anthropology at UVa provided me with a warm and nurturing space to develop as a scholar. I am most indebted to my dissertation chair and adviser, Richard Handler, for his unwavering support and encouragement without which I may never have been able to see this task to completion. I consider my work mostly a dialogue with what I have learned from him over these many years. I also want to extend my gratitude to the members of my committee. Dan Lefkowitz’s insights into performance helped me frame key aspects of my dissertation. Peter Metcalf consistently encouraged me to ground my theoretical arguments in ethnography, which I have tried to do. -

The Provenance of Arabic Loan-Words in a Phonological and Semantic Study. Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosoph

1 The Provenance of Arabic Loan-words Hausa:in a Phonological and Semantic study. Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the UNIVERSITY OF LONDON by Mohamed Helal Ahmed Sheref El-Shazly Volume One July 1987 /" 3ISL. \ Li/NDi V ProQuest Number: 10673184 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10673184 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 VOOUMEONE 3 ABSTRACT This thesis consists of an Introduction, three Chapters, and an Appendix. The corpus was obtained from the published dictionaries of Hausa together with additional material I gathered during a research visit to Northern Nigeria. A thorough examination of Hausa dictionaries yielded a large number of words of Arabic origin. The authors had not recognized all of these, and it was in no way their purpose to indicate whether the loan was direct or indirect; the dictionaries do not always give the Arabic origin, and sometimes their indications are inaccurate. The whole of my corpus amounts to some 4000 words, which are presented as an appendix. -

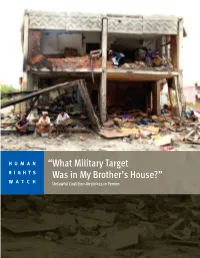

“What Military Target Was in My Brother's

H U M A N “What Military Target R I G H T S Was in My Brother’s House?” WATCH Unlawful Coalition Airstrikes in Yemen “What Military Target Was in My Brother’s House” Unlawful Coalition Airstrikes in Yemen Copyright © 2015 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-162431-33009 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org NOVEMBER 2015 978-162431-33009 “What Military Target Was in My Brother’s House” Unlawful Coalition Airstrikes in Yemen Summary ......................................................................................................................... 1 Recommendations .......................................................................................................... -

Muslim Cultural Awareness Course

Muslim Cultural Awareness Course Imam M Ismail Muslim Chaplain The University of Sheffield http://www.sheffield.ac.uk/ssid/chaplaincy/muslim/chaplain April 2017 Version Blank Page Cultural Awareness Course By M Ismail INTRODUCTION 2 THE BEGINNING OF ISLAM 4 MUSLIM BELIEFS 6 THE DUTIES OF A MUSLIM 8 JIHAD 10 THE HOLY QUR'AN 13 THE MOSQUE & MADRASAH 14 MUSLIM FAMILY LIFE 18 CARE FOR SELF 20 WOMENS HEADSCARF (HIJAB) 21 DIETARY RESTRICTIONS 26 MARRIAGE AND DIVORCE 28 DIVORCE 31 BIRTH, NAMES AND BIRTH CONTROL 33 DEATH AND BURIAL 35 MUSLIM FESTIVALS 37 MUSLIMS AND EDUCATION 38 MUSLIMS AND POLICE 41 MUSLIMS AND SOCIAL SERVICES 42 GLOSSARY TERMS COMMONLY USED BY MUSLIMS 43 1 INTRODUCTION Islam is the religion of about 1.6 billion people around the world and represents around 23% of the world's population. There are around three million Muslims in Britain, who originate from various parts of the world and some of them are of European origin. The majority of Muslims are from South Asian countries such as Pakistan, Bangladesh and India. Although, the British Muslim community varies from one group to another because of their different nationalities but they share their common beliefs with Muslims from other parts of the world. There may however, be some cultural differences and this is due to the varieties of different cultures in the life of British Muslims. The main focus of the discussion in this booklet is around the cultural and religious needs of the British Muslims. Religiously, there are two main Muslim groups in the world. -

Kukulage, Charika Samangi Perera Og Attestog, Targeir Oppgave

Mapping Extremist Forums using Text Mining Targeir Attestog, Samangi Perera Supervisor Professor Ole-Christoffer Granmo This Master’s Thesis is carried out as a part of the education at the University of Agder and is therefore approved as a part of this education. However, this does not imply that the University answers for the methods that are used or the conclusions that are drawn. University of Agder, 2013 Faculty of Engineering and Science Department of Information and Communication Technology Abstract Political opinions far from what is considered normal, a distorted view of reality, and hatred to certain other groups are spread amongst political extremists like Islamists and White Supremacists. Demonstrations and violence performed by some members of these groups are well-known from mass media and get a lot of attention. The Islamists and right-extremists exploit this benefit to spread their message to ordinary people. In online forums, young, curious people can read detailed information (or propaganda) from extremists. Which words do extremists then use to convince each other in addition to other curious readers that what they stand for is right? The goal of this thesis is to first find algorithms or techniques for how to discover characteristic vocabulary in online extremist forums and words that frequently are used in the same forum message. Then we analyse the results to find patterns of what is typical vocabulary in the different forums. Mapping the extremists’ habits of vocabulary usage can help us know better how extremists write in online extremist forums, and possibly also help us recognize them when they write on some other websites.