Try This at Home Series May 15, 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pu M Pkin Sw

Baked: Tuesdays & Thurs. Pumpkin Swirl Pumpkin 12268 Rockville Pike #A • Rockville, MD • 20852 • PH 301/770 - 8544 daily breads: Menu-Oct. 2015 Challah = 100% Whole Grain Bread Old Fashion White using hand-selected wheat, which we grind-fresh daily in our bakery. Honey Whole Wheat Dakota = >50% Whole Grain Bread Monday NE W Apple Scrapple * White Choc. Sour Cherry Swirl Cinnamon Blast * Cinnamon Chip Challah * Dakota * Popeye The perfect blend of real pumpkin, Tuesday NE W Pumpkin Swirl NE W Rosemary Garlic spices, walnuts, and streusel, hand- NEW Great Smokey Mountain * Popeye rolled into a light-wheat Loaf! Gluten Free ingredients breads—Brown Rice * Brown Rice Cinn. Chip PARVE Wednesday White Choc. Sour Cherry Swirl * Cinnamon Blast Available Daily in October. Cranberry Crunch * Parmesan Pesto NEW High-5-Fiber * Apple Scrapple Thursday NE W Pumpkin Swirl * Nine Grain Special Cherry Walnut * Cinn. Chip Challah * Cheddar Garlic * Choc. –or- Cinnamon Chip Babka Friday Cinnamon Blast Challah * Cinn. Challah * Raisin Challah White Choc. Sour Cherry Swirl NEW Woodstock Spinach Provolone * Choc. or Cinn Chip . Babka Saturday & Sunday NE W Apple Scrapple * Dakota Apple Bear Claw * Cinnamon Swirl * Spinach Provolone Choc. & Cinnamon Chip Babka Fall is a Cookie Buy individually or as a 6-pack Teacakes wonderful time Ginger Bops . .Daily Pumpkin Spice . Daily for apples!!! Choc. Chip Tollhouse . Daily Pumpkin Choc. Chip . Daily Chocolate Chip Oatmeal . .Th-Sun Chocolate Brownie . .Tues-Thu The trees are ripe Raisin Cinn. Oatmeal . .Th-Sun Jewish Apple Cake . .Thur-Sun with juicy apples Butterscotch Pecan . Sat.-Mon Muffin . Buy individually or as a 4-pack this time of year. -

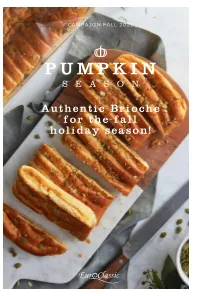

Pumpkin Season

CAMPAIGN FALL 2021 PUMPKIN SEASON Authentic Brioche for the fall holiday season! Pumpkin Brioche We were for Thanksgiving the trailblazers for Brioche is essential! in the US Key features · Our Brioche category • Authentic fillings. offers a traditional • Thaw & eat. French recipe. • Easy to handle: Fully baked retail items · It is a flavorful require no skilled labor. and tender artisan good • Artisanal appearance. Unique festive flavors that belongs to the category that consumers will be looking for in the fall. of bakery products. Fall Season • Convenient one touch product. 2021 Starts in September, · Rich and sweet, • Abundant Pumpkin pie filling and authentic Fall 2021 begins generally made on Wednesday, Pumpkin seeds Pumpkin brioche breads with eggs and butter. September 22nd and pastries perfect for entertaining during the Fall holiday season! Oct 26th · It was the croissant in 1984, Pumpkin Day then muffins, then bagels. Now, the world Oct 31st is ready for Brioche. Halloween · Brioche is perfect Nov 25th-26th compliment Thanksgiving to your dining table. Food Retail Service Ready Cross merchandise Place the products pumpkin filled together in the Brioche strudel store to create your and Pumpkin Twist own exciting fall Brioche with coffee season section. or tea to grab your consumers’ attention - an easy on-the-go breakfast. ORDER BY June 18th ASSORTMENT (Dinner Rolls until July 23rd) SOFT, SWEET & DELICIOUS!! NEW! FILLED BRIOCHE Pumpkin Filled Brioche Strudel This Thanksgiving, celebrate with our sweet, autumnal and gorgeously golden Pumpkin Strudel. 61577 Pumpkin Filled Brioche Strudel lf li life A The Pumpkin Filled Brioche Strudel is a soft brioche e fe lf h f e t S e h r full of real juicy pumpkin that will bring the wonderful aroma 16 u. -

Farmshop Bakery Product Guide 2018 Spring

bakery product guide descriptions ingredients allergens prices Spring 2018 Viennoiserie Butter Croissant FS1001 Flaky, buttery layers of laminated dough make up this traditional croissant. Using European-style butter helps make this pastry rich and delicious. Ingredients Organic Pastry Flour, Organic All-purpose Flour, Malt, Sugar, Salt, Yeast, Butter, Milk, Water, Organic Cage-free Eggs Allergens Gluten (Flour), Dairy (Butter, Milk), Eggs (Egg Wash) Price Wholesale $1.8; SRP $3.75 Almond Croissant FS1002 Using our butter croissant, we fill and cover the croissant with almond cream, sliced almonds and powdered sugar. Ingredients Croissant Organic Pastry Flour, Organic All-purpose Flour, Malt, Sugar, Salt, Yeast, Butter, Milk, Water, Organic Cage-free Eggs Almond Cream Organic Cage-free Eggs, Sugar, Almond Flour, Butter Allergens Gluten (Flour), Dairy (Butter, Milk), Eggs, Tree Nuts (Almonds) Price Wholesale $2.1; SRP $4.5 Chocolate Croissant/Pain au Chocolate FS100X Flaky croissant dough enrobing Belgian dark chocolate, hand crafted and baked until crispy. Ingredients Organic Pastry Flour, Organic All-purpose Flour, Malt, Sugar, Salt, Yeast, Butter, Milk, Water, Organic Cage-free Eggs Allergens Gluten (Flour), Dairy (Butter, Milk), Eggs (Egg Wash) Price Wholesale $1.95; SRP $4 Herb & Toma Danish FS1006 Danish dough is rolled out and topped with a blend of garlic oil, chives, chili flakes, and shredded Pt. Reyes Farmstead Toma Cheese. Ingredients Organic Pastry Flour, Organic All-purpose Flour, Malt, Sugar, Salt, Yeast, Butter, Milk, Water, Organic Cage-free Eggs, Garlic, Olive Oil, Chives, Red Pepper Flakes, Toma Cheese Allergens Gluten (Flour), Dairy (Butter, Milk), Eggs (Egg Wash), Nightshade (Red Pepper Flakes) Price Wholesale $2.1; SRP $4.5 Brioche Cinnamon Roll FS1008 Brioche dough hand rolled with cinnamon sugar pastry cream, baked and topped with crumb topping and glazed lightly with icing. -

Brunch Pastry & Croissant

BRUNCH PASTRY & CROISSANT Served daily 7am - 2pm in German Village CLASSIC CROISSANT $3 [nut-free] MUESLI & YOGURT $8 [vegetarian] Fage greek yogurt, toasted almond oat RYE CROISSANT $3 [nut-free] muesli, dried fruits (pears, cranberries, raisins & currants) & honey PAIN AU CHOCOLAT $4 [nut-free] croissant with semi-sweet chocolate batons BACON, SWISS CHARD & ONION QUICHE $11 [nut-free] pâte brisée, double smoked bacon, onion HAM & CHEESE CROISSANT $4.50 confit, swiss chard, comté cheese. served with [nut-free] with prosciutto ham & gruyère cheese dressed greens ALMOND CROISSANT $4.50 croissant soaked in a light brandy syrup, filled with almond MUSHROOM QUICHE $11 [vegetarian, nut-free] pâte brisée, crimini & shiitake frangipane mushrooms, shallots, aged emmentaler cheese, ORANGE BRIOCHE $3.50 parmigiano-reggiano. served with dressed greens [nut-free] brioche à tête with fresh orange zest CROQUE MONSIEUR $13 PAIN AUX RAISINS $4.50 [nut-free] house made brioche, smoked cottage [nut-free] danish dough with pastry cream, rum soaked raisins & ham, aged emmentaler cheese, mornay, Dijon a cinnamon glaze mustard, cornichons. served with dressed greens MAPLE PECAN TWIST $4.50 SMOKED SALMON “TARTARE” $14 danish dough, pecan frangipane, maple glaze & candied pecans [nut-free] Kendall Brook premium smoked salmon, crème fraîche, cucumber, tarragon, lemon, lime, POTATO, ONION & BLUE CHEESE GALETTE $6 shallot, cracked pepper. served with dressed greens [nut-free] puff pastry, yukon gold potato, caramelized onion & & toasted rye croissant blue cheese -

Download Catering Menu

Welcome to Croissants de France Let us introduce you to our catering department. We hope to have the privilege to work with you. www.croissantsdefrance.com 305-504-4155 [email protected] 1 Table of Contents 1- On site Brunch - page 5 2 -Outside Brunch - page 11 3- Dinner - page 15 4- Drop off trays and appetizers - page 23 5- Cakes - page 31 2 3 ON SITE BRUNCH Le Bistro Our restaurant accommodates up to 100 people, We offer complementary white linen and set up. The menus presented are flexible—See our complete Breakfast/lunch menu We have an extensive range of champagnes, mimosas, wines and beers. We also offer option for private area, white linen is included flowers upon request. 4 5 Breakfast Sample Brunch Sample OPTION ONE: A menu of six items accompanied by American coffee, OPTION ONE: A menu of six items accompanied by American coffee, tea or soda. $16.95 per person tea or soda. $15.95 per person OPTION TWO: A menu of six items accompanied by specialty coffees, OPTION TWO: A menu of six items accompanied by specialty coffees, teas, sodas and juices, plus homemade pastries and croissants upon arrival. $21.95 teas, sodas and juices, plus homemade pastries and croissants upon arrival. $20.95 Americano Bistro Breakfast Opened faced butter croissant topped with 3 scrambled eggs, dusted with paprika and scrambled eggs, cheddar, tomato, ham or Apple wood smoked bacon, scallions, served with a side of our grain mustards sauce and sautéed potatoes. served on Cuban bread or French baguette with roast potatoes Quiche Lorraine -

TBF Brochure.Pdf

1 ABOUT US ABOUT US In 1993, our founder Gail Stephens We’re still baking many of the original decided to turn back the clock on breads we baked at the beginning, industrialised baking practices and bake but we’re baking plenty of new breads bread as it used to be baked: by hand, now—as well as viennoiserie and cakes— using quality ingredients and time-worn on a daily basis too. We’re still delivering artisanal methods. to some of the best chefs and retailers in London , but we’re also now going a We’ve come a long way since those days bit further afield too. of Gail bringing together a handful of London’s best bakers. Yet the stuff that Fundamentally though, 25 years on matters – our ethos, suppliers, skill and from our founding, we still strongly our decades-old sourdough starter believe in that original mission—giving cultures – hasn’t changed. more people better access to the best- quality baked goods. This brochure shows a selection of our favourite breads, viennoiserie and cakes. If you’d like to know more about our full product range, please get in touch with your account manager or with our Customer Care team on: Phone: +44 (0)208 457 2080 Enquiries: [email protected] Our main bakery is not free from the following allergens: nuts, sesame seeds, gluten, milk, eggs and soya. However, we do have a gluten free bakery that is a separate unit and free from gluten. Our specialist gluten free range can be found at the back of this brochure. -

Apple & Raisin Brioche Pudding

APPLE & RAISIN BRIOCHE PUDDING ORIGINAL PRODUCT Bread & butter pudding is a traditional type of bread pudding, made by layering slices of (stale) buttered bread in a dish with raisins and an egg custard mixture, made with milk or cream. It is traditionally served as a hot pudding. Chef's Twist We have recreated this dessert through: Dawn Foods UK, Worcester Road, Texture – we have substituted the stale bread layers with a sweet, rich tasting brioche pastry, and also Evesham, WR11 4QU included apple pieces for an added texture dimension, to give a more indulgent dessert. Flavour – we have traded a standard egg custard filling for a more luxury creamy Crème Brulee style filling with the delicious taste of caramel, cream and vanilla. To complement this we have also included juicy Jonagold apple pieces with a sweet taste that makes for a more excellent dessert flavour. Temperature – this pudding can now be eaten cold, at room temperature, or heated – it is just as enjoyable whatever the serve! dawnfoods.com For more insights and solutions, contact us on 01386 760843 APPLE & RAISIN BRIOCHE PUDDING COMPOSITION ASSEMBLY Brioche Place some of the prepared brioche slices at the bottom of a pie dish (c.26cm). Top with 180g ® 1000g DAWN® Premium Raised Donut DAWN Delifruit Daily Apple and 20g California raisins. Pour two thirds of the crème brulee Base mix on top. 1000g Strong Bread Flour Place another layer of the brioche slices on top, 40g California raisins and top with the remaining crème brulee mix. 100g Yeast 960g Water Chill for a minimum of 2 hours, until set, and then serve. -

Breakfast Sandwiches Omelets

Madrone’s Curbside Brunch Menu Available from 10am‐2pm Saturday & Sunday Breakfast Sandwiches Country Ham Breakfast Sandwich – Two eggs, country ham, Tillamook aged cheddar, spicy Sriracha aioli, and arugula on a toasted brioche roll. $8.5 Avocado Breakfast Sandwich – Two eggs, Tillamook aged cheddar, smashed avocado, arugula, and spicy Sriracha aioli on a toasted brioche roll. $8.5 BLT Breakfast Sandwich – Two eggs, crispy bacon, tomato, Tillamook aged cheddar, spicy Sriracha aioli, and arugula on a toasted brioche roll. $8.5 Omelets All omelets are served with a bagel and a choice of: hash brown potatoes, spicy cheddar bacon grits, or sweet potato casserole WESTERN OMELET - Three whipped eggs, folded with sautéed onions, peppers, tomatoes & ham, with Tillamook aged cheddar. $12 GARDEN OMELET - Three whipped eggs, folded with grilled asparagus, mushrooms, baby spinach, tomato confit, and creamy brie cheese. $12 NAME YOUR OWN OMELET ‐ Make it your own with three ingredients of your choice. $12 Ingredients: Tomato Confit Cheddar Cheese Maple Turkey Green Onion Swiss Cheese Sausage Red Peppers Feta Cheese Andouille Sausage Green Pepper Goat Cheese Spicy Chorizo Onion Applewood- Shrimp $1 Mushroom Smoked Bacon Crab $3 Spinach Maple Sausage Additional Ingredient: +1 each. Breakfast Specialties Funky Monkey Bread – Pull apart sticky buns topped with cinnamon icing, caramel sauce, vanilla swirl, pecans and dusted with powdered sugar. $12 Home‐Style Breakfast – Three farm fresh eggs, hash brown potatoes, and your choice of applewood smoked bacon, sausage, or turkey sausage, and a bagel. $12 Brioche French Toast – Grilled house-made brioche bread dipped in vanilla honey batter, topped with sweet butter and dusted with powdered sugar. -

Code Des Usages De La Viennoiserie Artisanale Française

Code des usages de la viennoiserie artisanale française Code des usages viennoiserie artisanale – CNBPF / Pôle innovation INBP – Décembre 2013 1 Code des usages de la viennoiserie artisanale française Sommaire Préambule………………………………………………………………………………………………………..……p.4 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………..……p.5 Définitions et aspects réglementaires………………………………………..…………………………p.6 Note préliminaire………………………………………………………………………………………….………p.8 1. Pâtes levées……………………………………………………………………………………..…………p.9 1.1 Produits classiques en pâte levée………………………………………….………………p.9 1.1.1 Pâte à brioche………………………………………………………………………………..……p.9 Pâte à brioche, pâte à brioche fine et ses déclinaisons : brioche à tête ou parisienne ou Nanterre, brioche mousseline. Brioche feuilletée……………………………………………………………………………………...…p.12 Tresse russe………………………………………………………………………………………………..p.13 Roulé au chocolat…………………………………………………………………………………..……p.13 Roulé mixte……………………………………………………………………………………………..….p.14 1.1.2 Pâte levée sucrée……………………………………………………………..……………….p.15 Pâte levée sucrée et ses déclinaisons : couronne, tresse, boule au sucre. 1.1.2.1 Pâte à pain au lait………………………………………….…………………….p.15 Pâte à pain au lait et ses déclinaisons : pain au lait, boule, couronne, tresse et natte, animaux. 1.1.3 Cas particuliers……………………………………………………………….………………..p.17 Pain viennois et pain brioché Pâte feuilletée Beignets 1.2 Produits régionaux en pâte levée……………………………………………..…………p.18 Chinois (Alsace)………………………………………………………………………………………………..…..p.18 Gâteau au Streussel (Alsace)…………………………………………………………………………………..p.19 -

THE GUIDE 98.7Wfmt the Member Magazine Wfmt.Com for WTTW and WFMT

wttw11 wttw Prime wttw Create wttw World wttw PBS Kids wttw.com THE GUIDE 98.7wfmt The Member Magazine wfmt.com for WTTW and WFMT A CULTURAL AND CULINARY JOURNEY ACROSS AMERICA TUNE IN OR STREAM FRI DEC 20 9 PM December 2019 ALSO INSIDE WFMT will present a new special, Whole Notes: Music of Healing and Peace, in response to America’s gun violence epidemic and related to WTTW’s FIRSTHAND: Gun Violence initiative. From the President & CEO The Guide Dear Member, The Member Magazine for WTTW and WFMT Renowned chef, restaurateur, and author Marcus Samuelsson is passionate about Renée Crown Public Media Center the cuisine of America’s diverse immigrant cultures. This month, he returns with 5400 North Saint Louis Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60625 a new season of No Passport Required, where home cooks and professional chefs around the country share how important food can be in bringing us together around the table. Join us at 9:00 pm on December 20 for Marcus’s first stop, as he explores Main Switchboard (773) 583-5000 Seattle’s Filipino culinary traditions. And, in December, WTTW will be hosting a related Member and Viewer Services food tour event and creating digital content for you to feast on. The tour event and (773) 509-1111 x 6 stories will focus on a remarkably diverse half-mile stretch of a single Chicago street (Lawrence Avenue between Western and California) with a selection of restaurants Websites owned and run by immigrants, representing a variety of cuisines: Filipino, Vietnamese, wttw.com wfmt.com Bosnian and Serbian, Venezuelan, Korean, and Greek. -

Unit: 01 Basic Ingredients

Bakery Management BHM –704DT UNIT: 01 BASIC INGREDIENTS STRUCTURE 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Objectives 1.3 Sugar 1.4 Shortenings 1.5 Eggs 1.6 Wheat and flours 1.7 Milk and milk products 1.8 Yeast 1.9 Chemical leavening agents 1.10 Salt 1.11 Spices 1.12 Flavorings 1.13 Cocoa and Chocolate 1.14 Fruits and Nuts 1.15 Professional bakery equipment and tools 1.16 Production Factors 1.17 Staling and Spoilage 1.18 Summary 1.19 Glossary 1.20 Reference/Bibliography 1.21 Suggested Readings 1.22 Terminal Questions 1.1 INTRODUCTION Bakery ingredients have been used since ancient times and are of utmost importance these days as perhaps nothing can be baked without them. They are available in wide varieties and their preferences may vary according to the regional demands. Easy access of global information and exposure of various bakery products has increased the demand for bakery ingredients. Baking ingredients offer several advantages such as reduced costs, volume enhancement, better texture, colour, and flavour enhancement. For example, ingredients such enzymes improve protein solubility and reduce bitterness in end products, making enzymes one of the most preferred ingredients in the baking industry. Every ingredient in a recipe has a specific purpose. It's also important to know how to mix or combine the ingredients properly, which is why baking is sometimes referred to as a science. There are reactions in baking that are critical to a recipe turning out correctly. Even some small amount of variation can dramatically change the result. Whether its breads or cake, each ingredient plays a part. -

Frenchtoastrecipe

5/7/2020 BEST French Toast Recipe (just 15 minutes!) - I Heart Naptime French Toast Recipe French Toast - Fluffy brioche bread dipped in a vanilla and cinnamon mixture to make perfectly golden french toast. Top with powdered sugar, fresh berries and syrup for the ultimate breakfast. Say goodbye to soggy french toast for good with this easy recipe! Prep Time Cook Time Total Time 5 mins 10 mins 15 mins 5 from 4 votes Course: Breakfast Cuisine: French Keyword: french toast Servings: 6 Calories: 285kcal Author: Jamielyn Nye Ingredients 1 cup milk 1/4 cup all-purpose flour 4 large eggs 3 Tablespoons brown sugar 1 1/2 teaspoons vanilla extract 1 teaspoon ground cinnamon 1/8 teaspoon salt 1 Tablespoon butter 12 slices thick bread (I prefer brioche) Optional toppings: berries, fresh fruit, powdered sugar, nutella, whipped cream, jam, syrup Instructions 1. Place the milk, flour, eggs, brown sugar, vanilla, cinnamon and salt in a blender. Pulse until smooth. Alternatively place in a bowl and whisk until smooth. Preheat a griddle to 350°F or a skillet over medium-high heat. Butter before placing the bread on. Dip the bread into the egg mixture and flip to evenly coat. Then place the bread on the griddle and cook 2 minutes per side (or until lightly golden brown). Whisk the egg mixture as needed. Serve immediately or place on a baking sheet in the oven at 175°F to keep it warm. Top with your favorite toppings. Nutrition Calories: 285kcal | Carbohydrates: 40g | Protein: 11g | Fat: 8g | Saturated Fat: 3g | Cholesterol: 133mg | Sodium: 422mg | Potassium: 209mg | Fiber: 2g | Sugar: 11g | Vitamin A: 305IU | Calcium: 150mg | Iron: 2.8mg French Toast Recipe by I Heart Naptime Find full recipe notes and reviews here: https://www.iheartnaptime.net/french-toast/ https://www.iheartnaptime.net/french-toast/ 1/1.