A Gamelan Composition Portfolio with Commentary: Collaborative and Solo Processes of Composition with Reference to Javanese Karawitan and Cultural Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

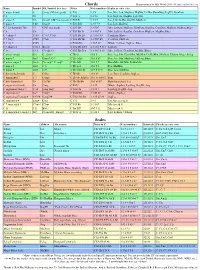

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM Chords Charts written by Mal Webb 2014-18 http://malwebb.com Name Symbol Alt. Symbol (best first) Notes Note numbers Scales (in order of fit). C major (triad) C Cmaj, CM (not good) C E G 1 3 5 Ion, Mix, Lyd, MajPent, MajBlu, DoHar, HarmMaj, RagPD, DomPent C 6 C6 C E G A 1 3 5 6 Ion, MajPent, MajBlu, Lyd, Mix C major 7 C∆ Cmaj7, CM7 (not good) C E G B 1 3 5 7 Ion, Lyd, DoHar, RagPD, MajPent C major 9 C∆9 Cmaj9 C E G B D 1 3 5 7 9 Ion, Lyd, MajPent C 7 (or dominant 7th) C7 CM7 (not good) C E G Bb 1 3 5 b7 Mix, LyDom, PhrDom, DomPent, RagCha, ComDim, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 9 C9 C E G Bb D 1 3 5 b7 9 Mix, LyDom, RagCha, DomPent, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 7 sharp 9 C7#9 C7+9, C7alt. C E G Bb D# 1 3 5 b7 #9 ComDim, Blues C 7 flat 9 C7b9 C7alt. C E G Bb Db 1 3 5 b7 b9 ComDim, PhrDom C 7 flat 5 C7b5 C E Gb Bb 1 3 b5 b7 Whole, LyDom, SupLoc, Blues C 7 sharp 11 C7#11 Bb+/C C E G Bb D F# 1 3 5 b7 9 #11 LyDom C 13 C 13 C9 add 13 C E G Bb D A 1 3 5 b7 9 13 Mix, LyDom, DomPent, MajBlu, Blues C minor (triad) Cm C-, Cmin C Eb G 1 b3 5 Dor, Aeo, Phr, HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin, MinPent, Ukdom, Blues, Pelog C minor 7 Cm7 Cmin7, C-7 C Eb G Bb 1 b3 5 b7 Dor, Aeo, Phr, MinPent, UkDom, Blues C minor major 7 Cm∆ Cm maj7, C- maj7 C Eb G B 1 b3 5 7 HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin C minor 6 Cm6 C-6 C Eb G A 1 b3 5 6 Dor, MelMin C minor 9 Cm9 C-9 C Eb G Bb D 1 b3 5 b7 9 Dor, Aeo, MinPent C diminished (triad) Cº Cdim C Eb Gb 1 b3 b5 Loc, Dim, ComDim, SupLoc C diminished 7 Cº7 Cdim7 C Eb Gb A(Bbb) 1 b3 b5 6(bb7) Dim C half diminished Cø -

3 Manual Microtonal Organ Ruben Sverre Gjertsen 2013

3 Manual Microtonal Organ http://www.bek.no/~ruben/Research/Downloads/software.html Ruben Sverre Gjertsen 2013 An interface to existing software A motivation for creating this instrument has been an interest for gaining experience with a large range of intonation systems. This software instrument is built with Max 61, as an interface to the Fluidsynth object2. Fluidsynth offers possibilities for retuning soundfont banks (Sf2 format) to 12-tone or full-register tunings. Max 6 introduced the dictionary format, which has been useful for creating a tuning database in text format, as well as storing presets. This tuning database can naturally be expanded by users, if tunings are written in the syntax read by this instrument. The freely available Jeux organ soundfont3 has been used as a default soundfont, while any instrument in the sf2 format can be loaded. The organ interface The organ window 3 MIDI Keyboards This instrument contains 3 separate fluidsynth modules, named Manual 1-3. 3 keysliders can be played staccato by the mouse for testing, while the most musically sufficient option is performing from connected MIDI keyboards. Available inputs will be automatically recognized and can be selected from the menus. To keep some of the manuals silent, select the bottom alternative "to 2ManualMicroORGANircamSpat 1", which will not receive MIDI signal, unless another program (for instance Sibelius) is sending them. A separate menu can be used to select a foot trigger. The red toggle must be pressed for this to be active. This has been tested with Behringer FCB1010 triggers. Other devices could possibly require adjustments to the patch. -

Helmholtz's Dissonance Curve

Tuning and Timbre: A Perceptual Synthesis Bill Sethares IDEA: Exploit psychoacoustic studies on the perception of consonance and dissonance. The talk begins by showing how to build a device that can measure the “sensory” consonance and/or dissonance of a sound in its musical context. Such a “dissonance meter” has implications in music theory, in synthesizer design, in the con- struction of musical scales and tunings, and in the design of musical instruments. ...the legacy of Helmholtz continues... 1 Some Observations. Why do we tune our instruments the way we do? Some tunings are easier to play in than others. Some timbres work well in certain scales, but not in others. What makes a sound easy in 19-tet but hard in 10-tet? “The timbre of an instrument strongly affects what tuning and scale sound best on that instrument.” – W. Carlos 2 What are Tuning and Timbre? 196 384 589 amplitude 787 magnitude sample: 0 10000 20000 30000 0 1000 2000 3000 4000 time: 0 0.23 0.45 0.68 frequency in Hz Tuning = pitch of the fundamental (in this case 196 Hz) Timbre involves (a) pattern of overtones (Helmholtz) (b) temporal features 3 Some intervals “harmonious” and others “discordant.” Why? X X X X 1.06:1 2:1 X X X X 1.89:1 3:2 X X X X 1.414:1 4:3 4 Theory #1:(Pythagoras ) Humans naturally like the sound of intervals de- fined by small integer ratios. small ratios imply short period of repetition short = simple = sweet Theory #2:(Helmholtz ) Partials of a sound that are close in frequency cause beats that are perceived as “roughness” or dissonance. -

Course Name : Indonesian Cultural Arts – Karawitan (Seni Budaya

Course Name : Indonesian Cultural Arts – Karawitan (Seni Budaya Indonesia – Karawitan) Course Code / Credits : BDU 2303/ 3 SKS Teaching Period : January-June Semester Language Instruction : Indonesian Department : Sastra Nusantara Faculty : Faculty of Arts and Humanities (FIB) Course Description The course of Indonesian Cultural Arts (Karawitan) is a compulsory course for (regular) students of Faculty of Cultural Sciences Universitas Gadjah Mada, especially for the first and second semesters. The course is held every semester and is offered and can be taken by every student from semester 1 to 2. There are no prerequisites for Karawitan courses. The position of Indonesian Culture Arts (Karawitan) as the compulsory course serves to introduce the students to one aspect of Indonesian (or Javanese) art and culture and the practical knowledge related to the performance of traditional Javanese musical instruments, namely gamelan. This course also aims to provide both introduction and theoretical and practical understanding for the students of the Faculty of Cultural Science on gamelan instrument techniques, namely gendhing technique, that is found in Karawitan. Topics in this course include identification of Javanese gamelan instruments, exploration of tones in Javanese gamelan, gendhing instrument method and practice, as well as observation of traditional art performances. Proportionally, 30% of these courses contains briefing theoretical insights, 40% contains gamelan practice, and 30% contains provision of experience in a form of group collaboration and interaction Course Objectives The course of Indonesian Culture Arts (Karawitan) in general aims to provide theoretical and practical supplies through skill, application, and carefulness to recognize various instruments of Gamelan. Through this course, students are observant in identifying the various instruments of the gamelan and its application as instrumental and vocal art in karawitan. -

Tuning: at the Grcssroads

WendyGarloo ?O. Box1024 Tuning:At the New YorkCit, New York 10276USA Grcssroads lntrodrciion planned the construction of instruments that per- formed within the new "tunitrg of choice," and all The arena o{ musical scales and tuning has cer_ publishedpapers or books demonstretingthe supe- tainly not been a quiet place to be for the past thlee dority of their new scales in at least some way over hundred yeals. But it might iust as well have beenif €qual temperament.The tradition has continued we iudge by the results: the same 12V2 equally with Yunik and Swi{t {1980),Blackwood (1982),and temperedscale established then as the best avail- the presentauthor (Milano 1986),and shows no able tuning compromise, by J. S. Bach and many sign of slowing down despite the apparent apathy otheis lHelrnholtz 1954j Apel 1972),remains to with which the musical mainstream has regularly this day essentially the only scale heard in Westem grceted eech new proposal. music. That monopoly crossesall musical styles, of course therc's a perf€ctly reasonable explana- {rom the most contemporary of jazz and av^rf,t' tion lor the mainstream's evident preferetrce to rc- "rut-bound" gardeclassical, and musical masteeieces from the main when by now there are at least past, to the latest technopop rock with fancy s)'n- a dozen clearly better-sounding ways to tune our thesizers,and everwvherein between.Instruments scales,i{ only for at least part of the time: it re' ol the symphonyorchestra a((empr with varyirrg quires a lot of effort ol several kinds. I'm typing this deSreesof successto live up ro lhe 100-centsemi manuscript using a Dvorak keyboard (lor the ffrst tone, even though many would find it inherently far time!), and I assureyou it's not easyto unlearn the easierto do otherwise: the stdngs to "lapse" into QWERTY habits of a lifetime, even though I can Pythagoieen tuning, the brass into several keys of akeady feel the actual superiodty of this unloved lust irtonation lBarbour 1953).And th€se easily but demonstrablv better kevboard. -

![Kraig Grady [Personal Data Omitted] Kraiggrady@Anaphoria.Com](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1901/kraig-grady-personal-data-omitted-kraiggrady-anaphoria-com-2981901.webp)

Kraig Grady [Personal Data Omitted] [email protected]

Kraig Grady [personal data omitted] [email protected] EDUCATION MCA-R Visual arts. Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts, University of Wollongong, 2014. John Cage mentions in one of his books of a student who went from school to school, finding the best teachers, taking their classes and then going on to other schools. This had a great impact on my young idealist mind and led me through a nine-year excursion through the following institutions: Los Angeles City College, California State Northridge, University of California Los Angeles, and finally Immaculate Heart College. Privately, I studied briefly with composers Nicolas Slonimsky, Dorrance Stalvey and more extensively with Byong-Kon Kim. This was in conjunction with years spent in libraries (downtown and UCLA). My studies with tuning theorist Erv Wilson were the longest, investigating microtonality, both in historical and cultural contexts, as well as the potential of unique scale designs and structures. EMPLOYMENT Casual lecturer in performance, Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 2008-2011. Subjects taught: THEA390, SCMP321, SCMP322. Scenic artist for various television stations, scenic companies and movie studios in Hollywood, including ABC, PBS, KTTV, KHJ, KTLA, Professional Scenery, etc, 1974-2005. Journeyman working on films such as Francis Ford Coppola’s One From The Heart, Brian De Palma’s Body Double, as well as various PBS productions, 1982-2005. ARTISTIC ACTIVITIES Composer/Performer/Instrument-Builder/Sound Artist All my music involves various microtonal tunings, 1975-present. Shadow Theatre Director Directed, produced, wrote, and scored eight shadow plays. I also made and operated 28 puppets that run the gamut from traditional sources to original designs. -

Module 4/Melody,Harmony,Texture

Module 4- Melody, Harmony and Texture Pitch in music refers to vibrations of sound waves. These vibrations are measured in hertz (cycles per second). Therefore a musical pitch is a sound produced at a certain number of cycles per second (Wade, 2013). The faster the vibration, the higher the resulting pitch. Likewise, the slower the rate of vibration, the lower the pitch. Musical tones can be divided into two cateGories: determinate and indeterminate pitch. Musical pitches contain a mixture of sound waves. The one that dominates the sound is referred to as the “fundamental” pitch. All of the other waves that are produced by a pitch are referred to (in the music world) as overtones. When a pitch has a set of overtones that allow a fundamental note to dominate the sound it is a determinate pitch. Indeterminate pitch happens when the overtones of a note are not in aliGnment or there are conflictinG fundamentals and therefore no “one” vibration dominates the sound. Another way to think about this concept is to know that instruments that have determinate pitch play notes that are typically Given names (letter, number or solfeGe). Determinate pitch instruments include (but are not limited to): voice, piano, Guitar, marimba, woodwinds, brass, chordophones, etc.… Indeterminate pitch instruments are instruments like Gamelan GonGs, snare drums, cymbals, trianGle, etc… These instruments are Generally used to keep a rhythm, to accent, or to add color. When a pitch has a set of overtones that vibrate alonG with the fundamental in simple ratios (see Figure 2) then it makes a harmonic pitch. -

Foundations in Music Psychology

Foundations in Music Psy chol ogy Theory and Research edited by Peter Jason Rentfrow and Daniel J. Levitin The MIT Press Cambridge, Mas sa chu setts London, England © 2019 Mas sa chu setts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was set in Stone Serif by Westchester Publishing Ser vices. Printed and bound in the United States of Amer i ca. Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Rentfrow, Peter J. | Levitin, Daniel J. Title: Foundations in music psy chol ogy : theory and research / edited by Peter Jason Rentfrow and Daniel J. Levitin. Description: Cambridge, MA : The MIT Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018018401 | ISBN 9780262039277 (hardcover : alk. paper) Subjects: LCSH: Music— Psychological aspects. | Musical perception. | Musical ability. Classification: LCC ML3830 .F7 2019 | DDC 781.1/1— dc23 LC rec ord available at https:// lccn . loc . gov / 2018018401 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents I Music Perception 1 Pitch: Perception and Neural Coding 3 Andrew J. Oxenham 2 Rhythm 33 Henkjan Honing and Fleur L. Bouwer 3 Perception and Cognition of Musical Timbre 71 Stephen McAdams and Kai Siedenburg 4 Pitch Combinations and Grouping 121 Frank A. Russo 5 Musical Intervals, Scales, and Tunings: Auditory Repre sen ta tions and Neural Codes 149 Peter Cariani II Music Cognition 6 Musical Expectancy 221 Edward W. Large and Ji Chul Kim 7 Musicality across the Lifespan 265 Sandra E. -

Dissonant Views on Consonance

Dissonant Views on Consonance The Cultural Dependency of Consonance and its Reinterpretation as Euphony June 2015 MA Thesis in Arts & Culture: Musicology First supervisor: Dr. Barbara Titus Second reader: Dr. Rutger Helmers Author: Tim Ruijgrok Student number: 10633014 Date: 18-06-2015 Contents Preface ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ 2 Chapter 1 - Consonant views on consonance? ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ 4 The cultural approach ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ 5 Chapter 2 - Consonance in the Western discourse ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ 11 Introduction to the case studies ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ 17 Chapter 3 - European common-practice and tonal consonance ∙ ∙ ∙ 20 The contrapuntal concept ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ 21 The triadic/tonal concept ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ 22 The sensory concept ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ 24 Chapter 4 - North-Indian classical music and the (absence of) harmony ∙ ∙ 29 Hindustani music ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ 31 Vādī & samvādī ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ 33 The tritone ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ 37 Chapter 5 - Javanese gamelan and inharmonic sounds ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ 40 Spectrum and timbre ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ 42 Conclusion ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ 45 Bibliography ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ ∙ 47 1 Preface During the two years of enrolment at the University of Amsterdam, my view towards diverse expressions of music has broadened significantly. Attending the UvA with the intention to potentially increase my knowledge or interest in Asian music, I followed the "cultural trajectory" of Musicology. I was fortunate to study Russian popular music and North-Indian (classical) music, both of which – I can conclude – have enriched my knowledge. I could not come closer to my objective in terms of education, hence I attempted to steer my thesis in that direction… however, to no avail. Being unable to put my knowledge into practice in my main field of interest, i.e. Asian music, I had to make the ultimate sacrifice and leave this out of my scope. This thesis is the result of a long struggle between my own expectations of it and the actual possibilities I felt I had. -

RESEARCH ARTICLE Metrics for Scales and Tunings

December 19, 2008 0:52 Journal of Mathematics and Music TuningMetric5 Journal of Mathematics and Music Vol. 00, No. 00, January 2009, 1–17 RESEARCH ARTICLE Metrics for Scales and Tunings a b Andrew J. Milne ∗ and William A. Sethares † aDepartment of Music, P.O. Box 35, FIN-40014, University of Jyvaskyl¨ a,¨ Finland; b1415 Engineering Drive, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706, USA (Received d mmmm yyyy; final version received d mmmm) yyyy We present a class of novel metrics for measuring the distance between any two pe- riodic scales whatever their precise tuning or cardinality. The metrics have some im- portant applications: (1) finding effective lower-dimensional temperaments of higher- dimensional tunings (such as just intonation); (2) finding simple scales that effectively approximate complex scales (e.g., using equally-tuned and well-formed scales to ap- proximate Fokker periodicity blocks and pairwise well-formed scales); (3) finding ways to map the notes of any arbitrary scale to a button lattice controller (a gen- eralized keyboard) so as to maximise geometrical consistency and playability; (4) comparing the distance of various scales (such as equal tunings with different num- bers of notes per octave) for analytical, maybe even compositional, purposes; (5) a generalized method to determine the similarity of different “pitch class sets” that is not dependent on the use of a low cardinality equal tunings such 12-tone, thus hinting at an approach towards a generalized theory of chord progression. Keywords: metric; tuning; scale; pitch class set; interval class vector; fourier transform; autocorrelation MCS/CCS/AMS Classification/CR Category numbers: ?????; ????? ∗Corresponding author. -

Music Theory Contents

Music theory Contents 1 Music theory 1 1.1 History of music theory ........................................ 1 1.2 Fundamentals of music ........................................ 3 1.2.1 Pitch ............................................. 3 1.2.2 Scales and modes ....................................... 4 1.2.3 Consonance and dissonance .................................. 4 1.2.4 Rhythm ............................................ 5 1.2.5 Chord ............................................. 5 1.2.6 Melody ............................................ 5 1.2.7 Harmony ........................................... 6 1.2.8 Texture ............................................ 6 1.2.9 Timbre ............................................ 6 1.2.10 Expression .......................................... 7 1.2.11 Form or structure ....................................... 7 1.2.12 Performance and style ..................................... 8 1.2.13 Music perception and cognition ................................ 8 1.2.14 Serial composition and set theory ............................... 8 1.2.15 Musical semiotics ....................................... 8 1.3 Music subjects ............................................. 8 1.3.1 Notation ............................................ 8 1.3.2 Mathematics ......................................... 8 1.3.3 Analysis ............................................ 9 1.3.4 Ear training .......................................... 9 1.4 See also ................................................ 9 1.5 Notes ................................................ -

Tarsos, a Modular Platform for Precise Pitch Analysis of Western and Non-Western Music

Tarsos, a Modular Platform for precise Pitch Analysis of Western and non-Western music Joren Six1, Olmo Cornelis1, and Marc Leman2 1University College Ghent, School of Arts Hoogpoort 64, 9000 Ghent - Belgium [email protected] [email protected] 2Ghent University, IPEM - Department of Musicology Blandijnberg 2, 9000 Ghent - Belgium [email protected] August 22, 2013 Abstract the piece under analysis. The extracted scale can be used immediately to tune a midi keyboard that can be played in the discovered scale. These features This paper presents Tarsos, a modular software plat- make Tarsos an interesting tool that can be used for form used to extract and analyze pitch organization musicological analysis, teaching and even artistic pro- in music. With Tarsos pitch estimations are gener- ductions. ated from an audio signal and those estimations are processed in order to form musicologically meaningful representations. Tarsos aims to offer a flexible sys- Keywords: Pitch Detection, Computa- tem for pitch analysis through the combination of an tional Ethnomusicology, Pitch Class His- interactive user interface, several pitch estimation al- togram, Tone Scale Extraction gorithms, filtering options, immediate auditory feed- back and data output modalities for every step. To study the most frequently used pitches, a fine-grained 1 Introduction histogram that allows up to 1200 values per octave is constructed. This allows Tarsos to analyze devi- In the past decennium, several computational tools ations in Western music, or to analyze specific tone became available for extracting pitch from audio scales that differ from the 12 tone equal tempera- recordings (Clarisse et al., 2002; Cheveign´e& Hideki, ment, common in many non-Western musics.