The Integration of Chinese Opera Traditions Into New Musical Compositions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spatiotemporal Changes and the Driving Forces of Sloping Farmland Areas in the Sichuan Region

sustainability Article Spatiotemporal Changes and the Driving Forces of Sloping Farmland Areas in the Sichuan Region Meijia Xiao 1 , Qingwen Zhang 1,*, Liqin Qu 2, Hafiz Athar Hussain 1 , Yuequn Dong 1 and Li Zheng 1 1 Agricultural Clean Watershed Research Group, Institute of Environment and Sustainable Development in Agriculture, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences/Key Laboratory of Agro-Environment, Ministry of Agriculture, Beijing 100081, China; [email protected] (M.X.); [email protected] (H.A.H.); [email protected] (Y.D.); [email protected] (L.Z.) 2 State Key Laboratory of Simulation and Regulation of Water Cycle in River Basin, China Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research, Beijing 100048, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-10-82106031 Received: 12 December 2018; Accepted: 31 January 2019; Published: 11 February 2019 Abstract: Sloping farmland is an essential type of the farmland resource in China. In the Sichuan province, livelihood security and social development are particularly sensitive to changes in the sloping farmland, due to the region’s large portion of hilly territory and its over-dense population. In this study, we focused on spatiotemporal change of the sloping farmland and its driving forces in the Sichuan province. Sloping farmland areas were extracted from geographic data from digital elevation model (DEM) and land use maps, and the driving forces of the spatiotemporal change were analyzed using a principal component analysis (PCA). The results indicated that, from 2000 to 2015, sloping farmland decreased by 3263 km2 in the Sichuan province. The area of gently sloping farmland (<10◦) decreased dramatically by 1467 km2, especially in the capital city, Chengdu, and its surrounding areas. -

IE Singapore Signs MOU with Sichuan (Chengdu) Free Trade Zone to Help Singapore Companies Gain Early Mover Advantage for Business Collaboration

M E D I A RELEASE IE Singapore signs MOU with Sichuan (Chengdu) Free Trade Zone to help Singapore companies gain early mover advantage for business collaboration MR No.: 027/17 Singapore, Wednesday, 28 June 2017 1. In continuous efforts to strengthen Singapore-Sichuan economic ties, International Enterprise (IE) Singapore signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the Commission of Commerce of Chengdu today to help Singapore companies expand their presence in Sichuan (Chengdu) Free Trade Zone (FTZ), specifically in Trade and Logistics, Financial and Professional Services, and Information Technology (IT) and Innovation. IE Singapore is the first foreign government agency to partner Chengdu’s Commission of Commerce on the FTZ, following China’s announcement on its third batch of seven FTZs, which includes Sichuan (Chengdu)1. 2. This MOU is the result of IE Singapore’s close consultation with the Chengdu local authorities and further enhances the strong economic relations established by the Singapore-Sichuan Trade and Investment Committee (SSTIC) co-chaired by Minister for Education (Schools) Ng Chee Meng. Building on the SSTIC’s work over the years, the MOU will explore collaboration beyond modern services, modern living and modern manufacturing. It will also benefit the Singapore-Sichuan Hi-Tech Innovation Park (SSCIP)2, which is situated in the FTZ and focuses on hi-tech and services industries. 3. Said Mr Lee Ark Boon, Chief Executive Officer (CEO), IE Singapore, who is currently leading a Singapore business delegation on a two-day mission to Chengdu, “Singapore was Chengdu’s second largest foreign investor in 2016. IE Singapore’s FTZ partnership builds on these existing close ties with Chengdu. -

Globalization and Theater Spectacles in Asia

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 15 (2013) Issue 2 Article 22 Globalization and Theater Spectacles in Asia I-Chun Wang National Sun Yat-sen University Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the American Studies Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, Education Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, Other Film and Media Studies Commons, Reading and Language Commons, Rhetoric and Composition Commons, Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, Television Commons, and the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Wang, I-Chun. -

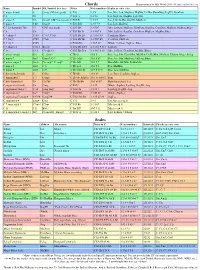

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM Chords Charts written by Mal Webb 2014-18 http://malwebb.com Name Symbol Alt. Symbol (best first) Notes Note numbers Scales (in order of fit). C major (triad) C Cmaj, CM (not good) C E G 1 3 5 Ion, Mix, Lyd, MajPent, MajBlu, DoHar, HarmMaj, RagPD, DomPent C 6 C6 C E G A 1 3 5 6 Ion, MajPent, MajBlu, Lyd, Mix C major 7 C∆ Cmaj7, CM7 (not good) C E G B 1 3 5 7 Ion, Lyd, DoHar, RagPD, MajPent C major 9 C∆9 Cmaj9 C E G B D 1 3 5 7 9 Ion, Lyd, MajPent C 7 (or dominant 7th) C7 CM7 (not good) C E G Bb 1 3 5 b7 Mix, LyDom, PhrDom, DomPent, RagCha, ComDim, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 9 C9 C E G Bb D 1 3 5 b7 9 Mix, LyDom, RagCha, DomPent, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 7 sharp 9 C7#9 C7+9, C7alt. C E G Bb D# 1 3 5 b7 #9 ComDim, Blues C 7 flat 9 C7b9 C7alt. C E G Bb Db 1 3 5 b7 b9 ComDim, PhrDom C 7 flat 5 C7b5 C E Gb Bb 1 3 b5 b7 Whole, LyDom, SupLoc, Blues C 7 sharp 11 C7#11 Bb+/C C E G Bb D F# 1 3 5 b7 9 #11 LyDom C 13 C 13 C9 add 13 C E G Bb D A 1 3 5 b7 9 13 Mix, LyDom, DomPent, MajBlu, Blues C minor (triad) Cm C-, Cmin C Eb G 1 b3 5 Dor, Aeo, Phr, HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin, MinPent, Ukdom, Blues, Pelog C minor 7 Cm7 Cmin7, C-7 C Eb G Bb 1 b3 5 b7 Dor, Aeo, Phr, MinPent, UkDom, Blues C minor major 7 Cm∆ Cm maj7, C- maj7 C Eb G B 1 b3 5 7 HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin C minor 6 Cm6 C-6 C Eb G A 1 b3 5 6 Dor, MelMin C minor 9 Cm9 C-9 C Eb G Bb D 1 b3 5 b7 9 Dor, Aeo, MinPent C diminished (triad) Cº Cdim C Eb Gb 1 b3 b5 Loc, Dim, ComDim, SupLoc C diminished 7 Cº7 Cdim7 C Eb Gb A(Bbb) 1 b3 b5 6(bb7) Dim C half diminished Cø -

SILK ROAD: the Silk Road

SILK ROAD: The Silk Road (or Silk Routes) is an extensive interconnected network of trade routes across the Asian continent connecting East, South, and Western Asia with the Mediterranean world, as well as North and Northeast Africa and Europe. FIDDLE/VIOLIN: Turkic and Mongolian horsemen from Inner Asia were probably the world’s earliest fiddlers (see below). Their two-stringed upright fiddles called morin khuur were strung with horsehair strings, played with horsehair bows, and often feature a carved horse’s head at the end of the neck. The morin khuur produces a sound that is poetically described as “expansive and unrestrained”, like a wild horse neighing, or like a breeze in the grasslands. It is believed that these instruments eventually spread to China, India, the Byzantine Empire and the Middle East, where they developed into instruments such as the Erhu, the Chinese violin or 2-stringed fiddle, was introduced to China over a thousand years ago and probably came to China from Asia to the west along the silk road. The sound box of the Ehru is covered with python skin. The erhu is almost always tuned to the interval of a fifth. The inside string (nearest to player) is generally tuned to D4 and the outside string to A4. This is the same as the two middle strings of the violin. The violin in its present form emerged in early 16th-Century Northern Italy, where the port towns of Venice and Genoa maintained extensive ties to central Asia through the trade routes of the silk road. The violin family developed during the Renaissance period in Europe (16th century) when all arts flourished. -

Performing Shakespeare in Contemporary Taiwan

Performing Shakespeare in Contemporary Taiwan by Ya-hui Huang A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Central Lancashire Jan 2012 Abstract Since the 1980s, Taiwan has been subjected to heavy foreign and global influences, leading to a marked erosion of its traditional cultural forms. Indigenous traditions have had to struggle to hold their own and to strike out into new territory, adopt or adapt to Western models. For most theatres in Taiwan, Shakespeare has inevitably served as a model to be imitated and a touchstone of quality. Such Taiwanese Shakespeare performances prove to be much more than merely a combination of Shakespeare and Taiwan, constituting a new fusion which shows Taiwan as hospitable to foreign influences and unafraid to modify them for its own purposes. Nonetheless, Shakespeare performances in contemporary Taiwan are not only a demonstration of hybridity of Westernisation but also Sinification influences. Since the 1945 Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party, or KMT) takeover of Taiwan, the KMT’s one-party state has established Chinese identity over a Taiwan identity by imposing cultural assimilation through such practices as the Mandarin-only policy during the Chinese Cultural Renaissance in Taiwan. Both Taiwan and Mainland China are on the margin of a “metropolitan bank of Shakespeare knowledge” (Orkin, 2005, p. 1), but it is this negotiation of identity that makes the Taiwanese interpretation of Shakespeare much different from that of a Mainlanders’ approach, while they share certain commonalities that inextricably link them. This study thus examines the interrelation between Taiwan and Mainland China operatic cultural forms and how negotiation of their different identities constitutes a singular different Taiwanese Shakespeare from Chinese Shakespeare. -

3 Manual Microtonal Organ Ruben Sverre Gjertsen 2013

3 Manual Microtonal Organ http://www.bek.no/~ruben/Research/Downloads/software.html Ruben Sverre Gjertsen 2013 An interface to existing software A motivation for creating this instrument has been an interest for gaining experience with a large range of intonation systems. This software instrument is built with Max 61, as an interface to the Fluidsynth object2. Fluidsynth offers possibilities for retuning soundfont banks (Sf2 format) to 12-tone or full-register tunings. Max 6 introduced the dictionary format, which has been useful for creating a tuning database in text format, as well as storing presets. This tuning database can naturally be expanded by users, if tunings are written in the syntax read by this instrument. The freely available Jeux organ soundfont3 has been used as a default soundfont, while any instrument in the sf2 format can be loaded. The organ interface The organ window 3 MIDI Keyboards This instrument contains 3 separate fluidsynth modules, named Manual 1-3. 3 keysliders can be played staccato by the mouse for testing, while the most musically sufficient option is performing from connected MIDI keyboards. Available inputs will be automatically recognized and can be selected from the menus. To keep some of the manuals silent, select the bottom alternative "to 2ManualMicroORGANircamSpat 1", which will not receive MIDI signal, unless another program (for instance Sibelius) is sending them. A separate menu can be used to select a foot trigger. The red toggle must be pressed for this to be active. This has been tested with Behringer FCB1010 triggers. Other devices could possibly require adjustments to the patch. -

CHENGDU CHINA Go Wild at Corbett

Mumbai,Saturday,August 14,2010 06 lifestyle htcafé PHOTOS: KALPANA SUNDER CHENGDU CHINA Go wild at Corbett Mongolia ways leave every 10 minutes be throughout the year.The Beijing Q&A from Madurai bus stand. Bijrani zone will be open CHENGDU Youcan stayinGujarat from October 15 and the inbox Bhawan, which is just a main Dhikala zone will be stone’s throw away from open fortourists from No- Gulyang Nepal My familyand Iare plan- Rameshwaramtemple. vember 15.Currently,the Qning to go to Maduraifor 2 roadstoJhirna zone are Philippines days. We’regoing to sightsee in Iwouldliketoknow not in good condition and Maduraionthe first dayand go Qduring which months the thereare severalstreams Take awalk to Rameshwaramthe next day. Corbett National Park is open on the way, filled with down colourful Anytips on what needs to be fortourists. Iamplanning to water.Itwill be better for Jinli street GETTING THERE seen?Please tell us about what visit in August or September; youtovisit Corbett to avoid. will it be open then?Also, how between November and By air: Youcan flytoChengdu Raviunni will the weather be during that February as it is winter from Beijing; it takes about two Meenakshi temple in time?Will we be able to enjoy time then and the animals hours. Or takeatrain AMadurai is amust see. the safari rides or would it be usually come out to the What to see: Panda park, Jinli Madurai is the centrefor toorainyand muddy? open grasslands to keep Street, Wohou Te mple, Leshan both Rameshwaramand Sumit themselves warm. If you Buddha Kanyakumari. Don’t take Sinceyou enquired want to visit the Dhikala the tour buses as therewill Aabout the opening sea- zone,then youhavetofile be arush foreverything son of the JimCorbett park, an application with the Cor- and youwon’t be able to see Iwould liketotell youthat, bett reception at least two the placespeacefully.Buses right now, the Jhirna zone months prior,for astay PANDA ADVENTURE of the Tamil Nadu Road- of the forest is open and will inside the park. -

Study on the Ecotourism Development in Dazhou

Open Journal of Social Sciences, 2018, 6, 24-34 http://www.scirp.org/journal/jss ISSN Online: 2327-5960 ISSN Print: 2327-5952 Study on the Ecotourism Development in Dazhou Xiaomei Pu1, Lin Tian2, Zibiao Cheng3 1Research Center of Sichuan Old Revolutionary Areas Development, Sichuan University of Arts and Science, Dazhou, China 2School of Foreign Languages, Sichuan University of Arts and Science, Dazhou, China 3School of Finance and Economics Management, Sichuan University of Arts and Science, Dazhou, China How to cite this paper: Pu, X.M., Tian, L. Abstract and Cheng, Z.B. (2018) Study on the Eco- tourism Development in Dazhou. Open After comprehensive discussion of the origin of ecotourism, the concept of Journal of Social Sciences, 6, 24-34. ecotourism and the theoretical basis for ecotourism development, the paper https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2018.65002 carried out the SWOT analysis on ecotourism development in Dazhou City, Received: April 8, 2018 and then proposed development strategies. The strategies were to: enhance Accepted: May 13, 2018 the ecological awareness of the entire people and create a good atmosphere for Published: May 16, 2018 ecotourism development; break the talent bottleneck of ecotourism develop- ment by adopting the policy of “combination boxing”; make scientific and Copyright © 2018 by authors and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. feasible master plan for Dazhou’s ecotourism development; develop quality This work is licensed under the Creative ecotourism products; innovate marketing strategies for ecotourism in Dazhou. Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0). Keywords http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Open Access Dazhou, Ecotourism, Development 1. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 142 4th International Conference on Education, Language, Art and Inter-cultural Communication (ICELAIC 2017) Study on the Protection of Han Opera Master Mi Yingxian’s Opera Culture On Its Historical Contribution to the Formation of Peking Opera Yifeng Wei School of Humanities and Media Hubei University of Science and Technology Xianning, China 437100 Abstract—Mi Yingxian, native of Hubei Chongyang, was the Opera History. Obviously, his main contribution in Chinese recognized founder of Peking opera. In the periods of Qianlong opera history is the promotion of birth of Peking opera. and Jiaqing, he brought his Hubei Han tune to Beijing. He Meanwhile, he was one of key figures in the promotion of Han became the leader role of Chuntai Troupe, one of the four Hui Opera Singing Art and the maturity of its performance form. troupes. Later, the Han tune converged with Hui tune, which And he also made a crucial contribution to the spread of Han marked the formation of Peking opera. Mi Yingxian was one of tune in Beijing. the key figures in the confluence of the Han tune and Hui tune. For two hundred years he was recognized as the ancestor of elderly male characters in Peking opera circle and has enjoyed a A. Mi Yingxian's Outstanding Position in the History of high reputation in the history of Chinese opera. But Chinese Opera unfortunately, such an important artistic master with national He made great contribution to the spread of Han Opera in influence hasn’t been paid enough attention in Xianning City northern area. -

Best-Performing Cities: China 2018

Best-Performing Cities CHINA 2018 THE NATION’S MOST SUCCESSFUL ECONOMIES Michael C.Y. Lin and Perry Wong MILKEN INSTITUTE | BEST-PERFORMING CITIES CHINA 2018 | 1 Acknowledgments The authors are grateful to Laura Deal Lacey, executive director of the Milken Institute Asia Center, Belinda Chng, the center’s director for policy and programs, and Ann-Marie Eu, the Institute’s senior associate for communications, for their support in developing this edition of our Best- Performing Cities series focused on China. We thank the communications team for their support in publication as well as Kevin Klowden, the executive director of the Institute’s Center for Regional Economics, Minoli Ratnatunga, director of regional economic research at the Institute, and our colleagues Jessica Jackson and Joe Lee for their constructive comments on our research. About the Milken Institute We are a nonprofit, nonpartisan think tank determined to increase global prosperity by advancing collaborative solutions that widen access to capital, create jobs, and improve health. We do this through independent, data-driven research, action-oriented meetings, and meaningful policy initiatives. About the Asia Center The Milken Institute Asia Center promotes the growth of inclusive and sustainable financial markets in Asia by addressing the region’s defining forces, developing collaborative solutions, and identifying strategic opportunities for the deployment of public, private, and philanthropic capital. Our research analyzes the demographic trends, trade relationships, and capital flows that will define the region’s future. About the Center for Regional Economics The Center for Regional Economics promotes prosperity and sustainable growth by increasing understanding of the dynamics that drive job creation and promote industry expansion. -

The Mercurian

The Mercurian : : A Theatrical Translation Review Volume 7, Number 3 (Spring 2019) Editor: Adam Versényi Editorial Assistant: Sarah Booker ISSN: 2160-3316 The Mercurian is named for Mercury who, if he had known it, was/is the patron god of theatrical translators, those intrepid souls possessed of eloquence, feats of skill, messengers not between the gods but between cultures, traders in images, nimble and dexterous linguistic thieves. Like the metal mercury, theatrical translators are capable of absorbing other metals, forming amalgams. As in ancient chemistry, the mercurian is one of the five elementary “principles” of which all material substances are compounded, otherwise known as “spirit.” The theatrical translator is sprightly, lively, potentially volatile, sometimes inconstant, witty, an ideal guide or conductor on the road. The Mercurian publishes translations of plays and performance pieces from any language into English. The Mercurian also welcomes theoretical pieces about theatrical translation, rants, manifestos, and position papers pertaining to translation for the theatre, as well as production histories of theatrical translations. Submissions should be sent to: Adam Versényi at [email protected] or by snail mail: Adam Versényi, Department of Dramatic Art, CB# 3230, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-3230. For translations of plays or performance pieces, unless the material is in the public domain, please send proof of permission to translate from the playwright or original creator of the piece. Since one of the primary objects of The Mercurian is to move translated pieces into production, no translations of plays or performance pieces will be published unless the translator can certify that he/she has had an opportunity to hear the translation performed in either a reading or another production-oriented venue.