Dissonant Views on Consonance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

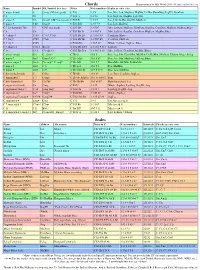

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM

Chords and Scales 30/09/18 3:21 PM Chords Charts written by Mal Webb 2014-18 http://malwebb.com Name Symbol Alt. Symbol (best first) Notes Note numbers Scales (in order of fit). C major (triad) C Cmaj, CM (not good) C E G 1 3 5 Ion, Mix, Lyd, MajPent, MajBlu, DoHar, HarmMaj, RagPD, DomPent C 6 C6 C E G A 1 3 5 6 Ion, MajPent, MajBlu, Lyd, Mix C major 7 C∆ Cmaj7, CM7 (not good) C E G B 1 3 5 7 Ion, Lyd, DoHar, RagPD, MajPent C major 9 C∆9 Cmaj9 C E G B D 1 3 5 7 9 Ion, Lyd, MajPent C 7 (or dominant 7th) C7 CM7 (not good) C E G Bb 1 3 5 b7 Mix, LyDom, PhrDom, DomPent, RagCha, ComDim, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 9 C9 C E G Bb D 1 3 5 b7 9 Mix, LyDom, RagCha, DomPent, MajPent, MajBlu, Blues C 7 sharp 9 C7#9 C7+9, C7alt. C E G Bb D# 1 3 5 b7 #9 ComDim, Blues C 7 flat 9 C7b9 C7alt. C E G Bb Db 1 3 5 b7 b9 ComDim, PhrDom C 7 flat 5 C7b5 C E Gb Bb 1 3 b5 b7 Whole, LyDom, SupLoc, Blues C 7 sharp 11 C7#11 Bb+/C C E G Bb D F# 1 3 5 b7 9 #11 LyDom C 13 C 13 C9 add 13 C E G Bb D A 1 3 5 b7 9 13 Mix, LyDom, DomPent, MajBlu, Blues C minor (triad) Cm C-, Cmin C Eb G 1 b3 5 Dor, Aeo, Phr, HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin, MinPent, Ukdom, Blues, Pelog C minor 7 Cm7 Cmin7, C-7 C Eb G Bb 1 b3 5 b7 Dor, Aeo, Phr, MinPent, UkDom, Blues C minor major 7 Cm∆ Cm maj7, C- maj7 C Eb G B 1 b3 5 7 HarmMin, MelMin, DoHarMin C minor 6 Cm6 C-6 C Eb G A 1 b3 5 6 Dor, MelMin C minor 9 Cm9 C-9 C Eb G Bb D 1 b3 5 b7 9 Dor, Aeo, MinPent C diminished (triad) Cº Cdim C Eb Gb 1 b3 b5 Loc, Dim, ComDim, SupLoc C diminished 7 Cº7 Cdim7 C Eb Gb A(Bbb) 1 b3 b5 6(bb7) Dim C half diminished Cø -

3 Manual Microtonal Organ Ruben Sverre Gjertsen 2013

3 Manual Microtonal Organ http://www.bek.no/~ruben/Research/Downloads/software.html Ruben Sverre Gjertsen 2013 An interface to existing software A motivation for creating this instrument has been an interest for gaining experience with a large range of intonation systems. This software instrument is built with Max 61, as an interface to the Fluidsynth object2. Fluidsynth offers possibilities for retuning soundfont banks (Sf2 format) to 12-tone or full-register tunings. Max 6 introduced the dictionary format, which has been useful for creating a tuning database in text format, as well as storing presets. This tuning database can naturally be expanded by users, if tunings are written in the syntax read by this instrument. The freely available Jeux organ soundfont3 has been used as a default soundfont, while any instrument in the sf2 format can be loaded. The organ interface The organ window 3 MIDI Keyboards This instrument contains 3 separate fluidsynth modules, named Manual 1-3. 3 keysliders can be played staccato by the mouse for testing, while the most musically sufficient option is performing from connected MIDI keyboards. Available inputs will be automatically recognized and can be selected from the menus. To keep some of the manuals silent, select the bottom alternative "to 2ManualMicroORGANircamSpat 1", which will not receive MIDI signal, unless another program (for instance Sibelius) is sending them. A separate menu can be used to select a foot trigger. The red toggle must be pressed for this to be active. This has been tested with Behringer FCB1010 triggers. Other devices could possibly require adjustments to the patch. -

Helmholtz's Dissonance Curve

Tuning and Timbre: A Perceptual Synthesis Bill Sethares IDEA: Exploit psychoacoustic studies on the perception of consonance and dissonance. The talk begins by showing how to build a device that can measure the “sensory” consonance and/or dissonance of a sound in its musical context. Such a “dissonance meter” has implications in music theory, in synthesizer design, in the con- struction of musical scales and tunings, and in the design of musical instruments. ...the legacy of Helmholtz continues... 1 Some Observations. Why do we tune our instruments the way we do? Some tunings are easier to play in than others. Some timbres work well in certain scales, but not in others. What makes a sound easy in 19-tet but hard in 10-tet? “The timbre of an instrument strongly affects what tuning and scale sound best on that instrument.” – W. Carlos 2 What are Tuning and Timbre? 196 384 589 amplitude 787 magnitude sample: 0 10000 20000 30000 0 1000 2000 3000 4000 time: 0 0.23 0.45 0.68 frequency in Hz Tuning = pitch of the fundamental (in this case 196 Hz) Timbre involves (a) pattern of overtones (Helmholtz) (b) temporal features 3 Some intervals “harmonious” and others “discordant.” Why? X X X X 1.06:1 2:1 X X X X 1.89:1 3:2 X X X X 1.414:1 4:3 4 Theory #1:(Pythagoras ) Humans naturally like the sound of intervals de- fined by small integer ratios. small ratios imply short period of repetition short = simple = sweet Theory #2:(Helmholtz ) Partials of a sound that are close in frequency cause beats that are perceived as “roughness” or dissonance. -

Playing Music in Just Intonation: a Dynamically Adaptive Tuning Scheme

Karolin Stange,∗ Christoph Wick,† Playing Music in Just and Haye Hinrichsen∗∗ ∗Hochschule fur¨ Musik, Intonation: A Dynamically Hofstallstraße 6-8, 97070 Wurzburg,¨ Germany Adaptive Tuning Scheme †Fakultat¨ fur¨ Mathematik und Informatik ∗∗Fakultat¨ fur¨ Physik und Astronomie †∗∗Universitat¨ Wurzburg¨ Am Hubland, Campus Sud,¨ 97074 Wurzburg,¨ Germany Web: www.just-intonation.org [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract: We investigate a dynamically adaptive tuning scheme for microtonal tuning of musical instruments, allowing the performer to play music in just intonation in any key. Unlike other methods, which are based on a procedural analysis of the chordal structure, our tuning scheme continually solves a system of linear equations, rather than relying on sequences of conditional if-then clauses. In complex situations, where not all intervals of a chord can be tuned according to the frequency ratios of just intonation, the method automatically yields a tempered compromise. We outline the implementation of the algorithm in an open-source software project that we have provided to demonstrate the feasibility of the tuning method. The first attempts to mathematically characterize is particularly pronounced if m and n are small. musical intervals date back to Pythagoras, who Examples include the perfect octave (m:n = 2:1), noted that the consonance of two tones played on the perfect fifth (3:2), and the perfect fourth (4:3). a monochord can be related to simple fractions Larger values of mand n tend to correspond to more of the corresponding string lengths (for a general dissonant intervals. If a normally consonant interval introduction see, e.g., Geller 1997; White and White is sufficiently detuned from just intonation (i.e., the 2014). -

Course Name : Indonesian Cultural Arts – Karawitan (Seni Budaya

Course Name : Indonesian Cultural Arts – Karawitan (Seni Budaya Indonesia – Karawitan) Course Code / Credits : BDU 2303/ 3 SKS Teaching Period : January-June Semester Language Instruction : Indonesian Department : Sastra Nusantara Faculty : Faculty of Arts and Humanities (FIB) Course Description The course of Indonesian Cultural Arts (Karawitan) is a compulsory course for (regular) students of Faculty of Cultural Sciences Universitas Gadjah Mada, especially for the first and second semesters. The course is held every semester and is offered and can be taken by every student from semester 1 to 2. There are no prerequisites for Karawitan courses. The position of Indonesian Culture Arts (Karawitan) as the compulsory course serves to introduce the students to one aspect of Indonesian (or Javanese) art and culture and the practical knowledge related to the performance of traditional Javanese musical instruments, namely gamelan. This course also aims to provide both introduction and theoretical and practical understanding for the students of the Faculty of Cultural Science on gamelan instrument techniques, namely gendhing technique, that is found in Karawitan. Topics in this course include identification of Javanese gamelan instruments, exploration of tones in Javanese gamelan, gendhing instrument method and practice, as well as observation of traditional art performances. Proportionally, 30% of these courses contains briefing theoretical insights, 40% contains gamelan practice, and 30% contains provision of experience in a form of group collaboration and interaction Course Objectives The course of Indonesian Culture Arts (Karawitan) in general aims to provide theoretical and practical supplies through skill, application, and carefulness to recognize various instruments of Gamelan. Through this course, students are observant in identifying the various instruments of the gamelan and its application as instrumental and vocal art in karawitan. -

Tuning: at the Grcssroads

WendyGarloo ?O. Box1024 Tuning:At the New YorkCit, New York 10276USA Grcssroads lntrodrciion planned the construction of instruments that per- formed within the new "tunitrg of choice," and all The arena o{ musical scales and tuning has cer_ publishedpapers or books demonstretingthe supe- tainly not been a quiet place to be for the past thlee dority of their new scales in at least some way over hundred yeals. But it might iust as well have beenif €qual temperament.The tradition has continued we iudge by the results: the same 12V2 equally with Yunik and Swi{t {1980),Blackwood (1982),and temperedscale established then as the best avail- the presentauthor (Milano 1986),and shows no able tuning compromise, by J. S. Bach and many sign of slowing down despite the apparent apathy otheis lHelrnholtz 1954j Apel 1972),remains to with which the musical mainstream has regularly this day essentially the only scale heard in Westem grceted eech new proposal. music. That monopoly crossesall musical styles, of course therc's a perf€ctly reasonable explana- {rom the most contemporary of jazz and av^rf,t' tion lor the mainstream's evident preferetrce to rc- "rut-bound" gardeclassical, and musical masteeieces from the main when by now there are at least past, to the latest technopop rock with fancy s)'n- a dozen clearly better-sounding ways to tune our thesizers,and everwvherein between.Instruments scales,i{ only for at least part of the time: it re' ol the symphonyorchestra a((empr with varyirrg quires a lot of effort ol several kinds. I'm typing this deSreesof successto live up ro lhe 100-centsemi manuscript using a Dvorak keyboard (lor the ffrst tone, even though many would find it inherently far time!), and I assureyou it's not easyto unlearn the easierto do otherwise: the stdngs to "lapse" into QWERTY habits of a lifetime, even though I can Pythagoieen tuning, the brass into several keys of akeady feel the actual superiodty of this unloved lust irtonation lBarbour 1953).And th€se easily but demonstrablv better kevboard. -

Tuning Continua and Keyboard Layouts

October 4, 2007 8:34 Journal of Mathematics and Music TuningContinua-RevisedVersion Journal of Mathematics and Music Vol. 00, No. 00, March 2007, 1–15 Tuning Continua and Keyboard Layouts ANDREW MILNE∗ , WILLIAM SETHARES , and JAMES PLAMONDON † ‡ § Department of Music, P.O. Box 35, FIN-40014, University of Jyvaskyl¨ a,¨ Finland. Email: [email protected] † 1415 Engineering Drive, Dept Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI 53706 USA. ‡ Phone: 608-262-5669. Email: [email protected] CEO, Thumtronics Inc., 6911 Thistle Hill Way, Austin, TX 78754 USA. Phone: 512-363-7094. Email: § [email protected] (received April 2007) Previous work has demonstrated the existence of keyboard layouts capable of maintaining consistent fingerings across a parameterised family of tunings. This paper describes the general principles underlying layouts that are invariant in both transposition and tuning. Straightforward computational methods for determining appropriate bases for a regular temperament are given in terms of a row-reduced matrix for the temperament-mapping. A concrete description of the range over which consistent fingering can be maintained is described by the valid tuning range. Measures of the resulting keyboard layouts allowdirect comparison of the ease with which various chordal and scalic patterns can be fingered as a function of the keyboard geometry. A number of concrete examples illustrate the generality of the methods and their applicability to a wide variety of commas and temperaments, tuning continua, and keyboard layouts. Keywords: Temperament; Comma; Layout; Button-Lattice; Swathe; Isotone 2000 Mathematics Subject Classification: 15A03; 15A04 1 Introduction Some alternative keyboard designs have the property that any given interval is fingered the same in all keys. -

Invariance of Controller Fingerings Across a Continuum of Tunings

Invariance of Controller Fingerings across a Continuum of Tunings Andrew Milne∗∗, William Setharesyy, and James Plamondonzz May 26, 2007 Introduction On the standard piano-style keyboard, intervals and chords have different shapes in each key. For example, the geometric pattern of the major third C–E is different from the geometric pattern of the major third D–F]. Similarly, the major scale is fingered differently in each of the twelve keys (in this usage, fingerings are specified without regard to which digits of the hand press which keys). Other playing surfaces, such as the keyboards of [Bosanquet, 1877] and [Wicki, 1896], have the property that each interval, chord, and scale type have the same geometric shape in every key. Such keyboards are said to be transpositionally invariant [Keisler, 1988]. There are many possible ways to tune musical intervals and scales, and the introduction of computer and software synthesizers makes it possible to realize any sound in any tuning [Carlos, 1987]. Typically, however, keyboard controllers are designed to play in a single tuning, such as the familiar 12-tone equal temperament (12-TET) which divides the octave into twelve perceptually equal pieces. Is it possible to create a keyboard surface that is capable of supporting many possible tunings? Is it possible to do so in a way that analogous musical intervals are fingered the same throughout the various tunings, so that (for example) the 12-TET fifth is fingered the same as the Just fifth and as the 17-TET fifth? (Just tunings ∗∗Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] yyDepartment of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53706 USA. -

Invariant Fingering Over a Tuning Continuum

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Isomorphic controllers and Dynamic Tuning: invariant fingering over a tuning continuum Journal Item How to cite: Milne, Andrew; Sethares, William and Plamondon, James (2007). Isomorphic controllers and Dynamic Tuning: invariant fingering over a tuning continuum. Computer Music Journal, 31(4) pp. 15–32. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2007 Massachusetts Institute of Technology Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1162/comj.2007.31.4.15 http://www.mitpressjournals.org/loi/comj Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Andrew Milne,* William Sethares,** and James Isomorphic Controllers and Plamondon† *Department of Music Dynamic Tuning: Invariant University of Jyväskylä Finland Fingering over a Tuning [email protected] **Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering Continuum University of Wisconsin-Madison Madison, WI 53706 USA [email protected] †Thumtronics Inc. 6911 Thistle Hill Way Austin, TX 78754 USA [email protected] In the Western musical tradition, two pitches are all within the time-honored framework of tonality. generally considered the “same” if they have nearly Such novel musical effects are discussed briefly in equal fundamental frequencies. Likewise, two the section on dynamic tuning, but the bulk of this pitches are in the “same” pitch class if the frequency article deals with the mathematical and perceptual of one is a power-of-two multiple of the other. -

Beyond the Spectrum of Music: an Exploration

BEYOND THE SPECTRUM OF MUSIC: AN EXPLORATION THROUGH SPECTRAL ANALYSIS OF SOUND COLOR IN THE ALBAN BERG VIOLIN CONCERTO by Diego Bañuelos A written project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts (Music) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN-MADISON 2005 © Copyright by Diego Banuelos 2005 All Rights Reserved To Cathy Ann Elias ii CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . iii SOUND EXAMPLES . vi PART I: INTRODUCTION . 1 PART II: ANALYTICAL PROCEDURES. 14 Spectrum and Spectrogram . 14 Noise and Peaks . 20 Plotting Single Attributes of Sound . 27 Dimensions in Sound Color and the Purpose of Spectral Analysis. 27 Sensory Roughness (SR) . 30 Registral and Timbral Brightness (RB and TB) . 39 Peak Variance (PV) . 42 Noise to Signal Ratio (NSR) . 44 Summary . 47 PART III: SPECTRUM-BASED ANALYSIS OF ALBAN BERG’S VIOLIN CONCERTO (SECOND MOVEMENT) . 48 Micro-Structure . 53 Macro-Structure: Movement II in Continuity . 69 Conclusion . 80 APPENDIX A: SR, PV, NSR, RB, and TB graphs of the Berg Violin Concerto (movement II) . 84 APPENDIX B: Spectrograms of the Berg Violin Concerto (movement II) . 89 WORKS CITED . 110 iii ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 2.1 Spectrogram of the first six measures of Alban Berg’s Violin Concerto, movement II . 14 2.2 Spectrum of a violin open A-string analyzed over a period of 0.19 seconds 17 2.3 Stages in the construction of the spectrogram . 19 2.4 Spectrum and noise floor of a violin A-string . 22 2.5 Two spectral representations of a violin A-string. 26 2.6 Succinct representation of a Plomp and Levelt curve. -

![Kraig Grady [Personal Data Omitted] Kraiggrady@Anaphoria.Com](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1901/kraig-grady-personal-data-omitted-kraiggrady-anaphoria-com-2981901.webp)

Kraig Grady [Personal Data Omitted] [email protected]

Kraig Grady [personal data omitted] [email protected] EDUCATION MCA-R Visual arts. Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts, University of Wollongong, 2014. John Cage mentions in one of his books of a student who went from school to school, finding the best teachers, taking their classes and then going on to other schools. This had a great impact on my young idealist mind and led me through a nine-year excursion through the following institutions: Los Angeles City College, California State Northridge, University of California Los Angeles, and finally Immaculate Heart College. Privately, I studied briefly with composers Nicolas Slonimsky, Dorrance Stalvey and more extensively with Byong-Kon Kim. This was in conjunction with years spent in libraries (downtown and UCLA). My studies with tuning theorist Erv Wilson were the longest, investigating microtonality, both in historical and cultural contexts, as well as the potential of unique scale designs and structures. EMPLOYMENT Casual lecturer in performance, Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 2008-2011. Subjects taught: THEA390, SCMP321, SCMP322. Scenic artist for various television stations, scenic companies and movie studios in Hollywood, including ABC, PBS, KTTV, KHJ, KTLA, Professional Scenery, etc, 1974-2005. Journeyman working on films such as Francis Ford Coppola’s One From The Heart, Brian De Palma’s Body Double, as well as various PBS productions, 1982-2005. ARTISTIC ACTIVITIES Composer/Performer/Instrument-Builder/Sound Artist All my music involves various microtonal tunings, 1975-present. Shadow Theatre Director Directed, produced, wrote, and scored eight shadow plays. I also made and operated 28 puppets that run the gamut from traditional sources to original designs. -

Module 4/Melody,Harmony,Texture

Module 4- Melody, Harmony and Texture Pitch in music refers to vibrations of sound waves. These vibrations are measured in hertz (cycles per second). Therefore a musical pitch is a sound produced at a certain number of cycles per second (Wade, 2013). The faster the vibration, the higher the resulting pitch. Likewise, the slower the rate of vibration, the lower the pitch. Musical tones can be divided into two cateGories: determinate and indeterminate pitch. Musical pitches contain a mixture of sound waves. The one that dominates the sound is referred to as the “fundamental” pitch. All of the other waves that are produced by a pitch are referred to (in the music world) as overtones. When a pitch has a set of overtones that allow a fundamental note to dominate the sound it is a determinate pitch. Indeterminate pitch happens when the overtones of a note are not in aliGnment or there are conflictinG fundamentals and therefore no “one” vibration dominates the sound. Another way to think about this concept is to know that instruments that have determinate pitch play notes that are typically Given names (letter, number or solfeGe). Determinate pitch instruments include (but are not limited to): voice, piano, Guitar, marimba, woodwinds, brass, chordophones, etc.… Indeterminate pitch instruments are instruments like Gamelan GonGs, snare drums, cymbals, trianGle, etc… These instruments are Generally used to keep a rhythm, to accent, or to add color. When a pitch has a set of overtones that vibrate alonG with the fundamental in simple ratios (see Figure 2) then it makes a harmonic pitch.