“Dynamic Speciation Processes in the Mediterranean Orchid Genus Ophrys L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nitrogen Containing Volatile Organic Compounds

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit Nitrogen containing Volatile Organic Compounds Verfasserin Olena Bigler angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Pharmazie (Mag.pharm.) Wien, 2012 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 996 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Pharmazie Betreuer: Univ. Prof. Mag. Dr. Gerhard Buchbauer Danksagung Vor allem lieben herzlichen Dank an meinen gütigen, optimistischen, nicht-aus-der-Ruhe-zu-bringenden Betreuer Herrn Univ. Prof. Mag. Dr. Gerhard Buchbauer ohne dessen freundlichen, fundierten Hinweisen und Ratschlägen diese Arbeit wohl niemals in der vorliegenden Form zustande gekommen wäre. Nochmals Danke, Danke, Danke. Weiteres danke ich meinen Eltern, die sich alles vom Munde abgespart haben, um mir dieses Studium der Pharmazie erst zu ermöglichen, und deren unerschütterlicher Glaube an die Fähigkeiten ihrer Tochter, mich auch dann weitermachen ließ, wenn ich mal alles hinschmeissen wollte. Auch meiner Schwester Ira gebührt Dank, auch sie war mir immer eine Stütze und Hilfe, und immer war sie da, für einen guten Rat und ein offenes Ohr. Dank auch an meinen Sohn Igor, der mit viel Verständnis akzeptierte, dass in dieser Zeit meine Prioritäten an meiner Diplomarbeit waren, und mein Zeitbudget auch für ihn eingeschränkt war. Schliesslich last, but not least - Dank auch an meinen Mann Joseph, der mich auch dann ertragen hat, wenn ich eigentlich unerträglich war. 2 Abstract This review presents a general analysis of the scienthr information about nitrogen containing volatile organic compounds (N-VOC’s) in plants. -

Charles Darwin: a Companion

CHARLES DARWIN: A COMPANION Charles Darwin aged 59. Reproduction of a photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron, original 13 x 10 inches, taken at Dumbola Lodge, Freshwater, Isle of Wight in July 1869. The original print is signed and authenticated by Mrs Cameron and also signed by Darwin. It bears Colnaghi's blind embossed registration. [page 3] CHARLES DARWIN A Companion by R. B. FREEMAN Department of Zoology University College London DAWSON [page 4] First published in 1978 © R. B. Freeman 1978 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of the publisher: Wm Dawson & Sons Ltd, Cannon House Folkestone, Kent, England Archon Books, The Shoe String Press, Inc 995 Sherman Avenue, Hamden, Connecticut 06514 USA British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Freeman, Richard Broke. Charles Darwin. 1. Darwin, Charles – Dictionaries, indexes, etc. 575′. 0092′4 QH31. D2 ISBN 0–7129–0901–X Archon ISBN 0–208–01739–9 LC 78–40928 Filmset in 11/12 pt Bembo Printed and bound in Great Britain by W & J Mackay Limited, Chatham [page 5] CONTENTS List of Illustrations 6 Introduction 7 Acknowledgements 10 Abbreviations 11 Text 17–309 [page 6] LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Charles Darwin aged 59 Frontispiece From a photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron Skeleton Pedigree of Charles Robert Darwin 66 Pedigree to show Charles Robert Darwin's Relationship to his Wife Emma 67 Wedgwood Pedigree of Robert Darwin's Children and Grandchildren 68 Arms and Crest of Robert Waring Darwin 69 Research Notes on Insectivorous Plants 1860 90 Charles Darwin's Full Signature 91 [page 7] INTRODUCTION THIS Companion is about Charles Darwin the man: it is not about evolution by natural selection, nor is it about any other of his theoretical or experimental work. -

Pollinator Attraction in a Sexually Deceptive Orchid by Means of Unconventional Chemicals Manfred Ayasse1*, Florian P

Received 19 August 2002 FirstCite Accepted 12 November 2002 e-publishing Published online Pollinator attraction in a sexually deceptive orchid by means of unconventional chemicals Manfred Ayasse1*, Florian P. Schiestl1†, Hannes F. Paulus1, Fernando Ibarra2 and Wittko Francke2 1Institute of Zoology, Department of Evolutionary Biology, University of Vienna, Althanstrasse 14, A-1090 Vienna, Austria 2Department of Organic Chemistry, Universita¨t Hamburg, Martin Luther King Platz 6, D-20146 Hamburg, Germany Ophrys flowers mimic virgin females of their pollinators, and thereby attract males for pollination. Stimu- lated by scent, the males attempt to copulate with flower labella and thereby ensure pollination. Here, we show for the first time, to our knowledge, that pollinator attraction in sexually deceptive orchids may be based on a few specific chemical compounds. Ophrys speculum flowers produce many volatiles, including trace amounts of (ω-1)-hydroxy and (ω-1)-oxo acids, especially 9-hydroxydecanoic acid. These com- pounds, which are novel in plants, prove to be the major components of the female sex pheromone in the scoliid wasp Campsoscolia ciliata, and stimulate male copulatory behaviour in this pollinator species. The specificity of the signal depends primarily on the structure and enantiomeric composition of the oxygenated acids, which is the same in wasps and in the orchids. The overall composition of the blend differs significantly between the orchid and its pollinator and is of secondary importance. 9-Hydroxyde- canoic acid is a rarely occurring compound that until now has been identified only in honeybees. Contrary to the standard hypothesis that Ophrys flowers produce only ‘second-class attractivity compounds’ and are neglected once the pollinator females are present, we show that flowers are more attractive to the males than are their own females. -

Review Article Conservation Status of the Family Orchidaceae in Spain Based on European, National, and Regional Catalogues of Protected Species

Hind ile Scientific Volume 2018, Article ID 7958689, 18 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/7958689 Hindawi Review Article Conservation Status of the Family Orchidaceae in Spain Based on European, National, and Regional Catalogues of Protected Species Daniel de la Torre Llorente© Biotechnology-Plant Biology Department, Higher Technical School of Agronomic, Food and Biosystems Engineering, Universidad Politecnica de Madrid, 28140 Madrid, Spain Correspondence should be addressed to Daniel de la Torre Llorente; [email protected] Received 22 June 2017; Accepted 28 December 2017; Published 30 January 2018 Academic Editor: Antonio Amorim Copyright © 2018 Daniel de la Torre Llorente. Tis is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Tis report reviews the European, National, and Regional catalogues of protected species, focusing specifcally on the Orchidaceae family to determine which species seem to be well-protected and where they are protected. Moreover, this examination highlights which species appear to be underprotected and therefore need to be included in some catalogues of protection or be catalogued under some category of protection. Te national and regional catalogues that should be implemented are shown, as well as what species should be included within them. Tis report should be a helpful guideline for environmental policies about orchids conservation in Spain, at least at the regional and national level. Around 76% of the Spanish orchid fora are listed with any fgure of protection or included in any red list, either nationally (about 12-17%) or regionally (72%). -

166. Ophrys Scolopax × Ophrys Speculum (Orchidaceae), First Record for the Iberian Flora

226 Acta Botanica Malacitana 37. 2012 166. OPHRYS SCOLOPAX × OPHRYS SPECULUM (ORCHIDACEAE), FIRST RECORD FOR THE IBERIAN FLORA. Juan PÉREZ-CONTRERAS1* & Mick RICHARDSON2 Recibido el 12 de abril de 2012, aceptado para su publicación el 13 de abril de 2012 Primera cita de Ophrys scolopax × Ophrys speculum (Orchidaceae) para la Flora Ibérica. Palabras clave. Orchidaceae, Ophrys, híbrido, Málaga, Península Ibérica, España. Key words. Orchidaceae, Ophrys, hybrid, Malaga, Iberian Peninsula, Spain. Natural hybridization is frequent within floral characters (mainly in petals, lateral Orchidaceae family, especially between labellum lobes and speculum) suggesting the members of the Ophrys L. genus (Delforge, interspecific hybridOphrys scolopax × Ophrys 2006). speculum was found in the wild in Malaga On the 19th of March 2011, a single province by the authors. The plant was growing specimen of a plant showing intermediate in the middle of a colony of its parent species, Ophrys scolopax Cav. & Ophrys speculum subsp. Link speculum, in a pine woodland area in the northwest face of Sierra de Mijas (Alhaurín el Grande). Photographs were taken (fig. 1) and the images sent to experts confirmed the correct identification (Delforge & Lowe, com. pers.). According to the literature, there is no mention of this taxon neither in the Flora Ibérica (Aedo & Herrero, 2005) nor in the Vascular Flora of Eastern Andalusia (Blanca et al., 2011). These new data represent the first record of this hybrid in the Iberian Peninsula. Ophrys scolopax × Ophrys speculum MÁLAGA: UTM 30S UF45, 340 m. Sierra de Mijas, Alhaurín el Grande, 19-III-2011. J. Pérez-Contreras & M. Richardson. REFERENCES AEDO, C. & A. HERRERO (eds.) -2005- Flora Figure 1. -

Actes Du 15E Colloque Sur Les Orchidées De La Société Française D’Orchidophilie

Cah. Soc. Fr. Orch., n° 7 (2010) – Actes 15e colloque de la Société Française d’Orchidophilie, Montpellier Actes du 15e colloque sur les Orchidées de la Société Française d’Orchidophilie du 30 mai au 1er juin 2009 Montpellier, Le Corum Comité d’organisation : Daniel Prat, Francis Dabonneville, Philippe Feldmann, Michel Nicole, Aline Raynal-Roques, Marc-Andre Selosse, Bertrand Schatz Coordinateurs des Actes Daniel Prat & Bertrand Schatz Affiche du Colloque : Conception : Francis Dabonneville Photographies de Francis Dabonneville & Bertrand Schatz Cahiers de la Société Française d’Orchidophilie, N° 7, Actes du 15e Colloque sur les orchidées de la Société Française d’Orchidophilie. ISSN 0750-0386 © SFO, Paris, 2010 Certificat d’inscription à la commission paritaire N° 55828 ISBN 978-2-905734-17-4 Actes du 15e colloque sur les Orchidées de la Société Française d’Orchidophilie, D. Prat et B. Schatz, Coordinateurs, SFO, Paris, 2010, 236 p. Société Française d’Orchidophilie 17 Quai de la Seine, 75019 Paris Cah. Soc. Fr. Orch., n° 7 (2010) – Actes 15e colloque de la Société Française d’Orchidophilie, Montpellier Préface Ce 15e colloque marque le 40e anniversaire de notre société, celle-ci ayant vu le jour en 1969. Notre dernier colloque se tenait il y a 10 ans à Paris en 1999, 10 ans c’est long, 10 ans c’est très loin. Il fallait que la SFO renoue avec cette traditionnelle organisation de colloques, manifestation qui a contribué à lui accorder la place prépondérante qu’elle occupe au sein des orchidophiles français et de la communauté scientifique. C’est chose faite aujourd’hui. Nombreux sont les thèmes qui font l’objet de communications par des intervenants dont les compétences dans le domaine de l’orchidologie ne sont plus à prouver. -

Five Established Orchids Ophrys Apifera Var

FIVE ESTABLISHED ORCHIDS OPHRYS APIFERA VAR. CHLORANTHA, AURITA, PURPUREA, PURPUREA. F. ALBA. AND FLAVESCENS (ORCHIDACEAE) IN LEBANON AS PART OF THE NATIVE FLORA. ADDAM K.*1, TAKKOUSH J.1, BOU-HAMDAN M.2 AND ITANI J.3 1Faculty of Business Administration, Research department, Arts, Sciences and Technology University in Lebanon, AUL 2Clinker Production Unit at Ciment De Sibline (LCF: Lebanese Cement Factory). 3Faculty of Sciences and Fine Arts, Arts, Sciences and Technology University in Lebanon, AUL *Corresponding Author: Email- [email protected] Received: November 11, 2015; Revised: November 16, 2015; Accepted: November 17, 2015 Citation: Addam K., et al., (2015) Five Established Orchids Ophrys apifera var. Chlorantha, Aurita, Purpurea, Purpurea. F. Alba. and Flavescens (Orchidaceae) in Lebanon as Part of the Native Flora. Journal of Ecology and Environmental Sciences, ISSN: 0976-9900 & E-ISSN: 0976-9919, Volume 6, Issue 2, pp.-163-169. Copyright: Copyright©2015 Addam K., et al., This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Introduction species became a total of 130. [6] Six years later (2001), he raised the number to Among all the angiosperm plants, the family of the Orchidaceae is considered to 215 species. This was the last classification set and accepted by him [4]. be the largest. It includes more than 22,000 accepted species in 880 genera. The great conflict and main problem of Orchids classification is still a worldwide Two principal large groups divide the Orchids: debate among the scientists and botanists who have dissimilar points of view in this field and without finding a solution for it till now [7]. -

Phylogenetics of Tribe Orchideae (Orchidaceae: Orchidoideae)

Annals of Botany 110: 71–90, 2012 doi:10.1093/aob/mcs083, available online at www.aob.oxfordjournals.org Phylogenetics of tribe Orchideae (Orchidaceae: Orchidoideae) based on combined DNA matrices: inferences regarding timing of diversification and evolution of pollination syndromes Luis A. Inda1,*, Manuel Pimentel2 and Mark W. Chase3 1Escuela Polite´cnica Superior de Huesca, Universidad de Zaragoza, carretera de Cuarte sn. 22071 Huesca, Spain, 2Facultade de Ciencias, Universidade da Corun˜a, Campus da Zapateira sn. 15071 A Corun˜a, Spain and 3Jodrell Laboratory, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 3DS, UK * For correspondence. E-mail [email protected] Received: 3 November 2011 Returned for revision: 9 December 2011 Accepted: 1 March 2012 Published electronically: 25 April 2012 † Background and aims Tribe Orchideae (Orchidaceae: Orchidoideae) comprises around 62 mostly terrestrial genera, which are well represented in the Northern Temperate Zone and less frequently in tropical areas of both the Old and New Worlds. Phylogenetic relationships within this tribe have been studied previously using only nuclear ribosomal DNA (nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer, nrITS). However, different parts of the phylogenetic tree in these analyses were weakly supported, and integrating information from different plant genomes is clearly necessary in orchids, where reticulate evolution events are putatively common. The aims of this study were to: (1) obtain a well-supported and dated phylogenetic hypothesis for tribe Orchideae, (ii) assess appropriateness of recent nomenclatural changes in this tribe in the last decade, (3) detect possible examples of reticulate evolution and (4) analyse in a temporal context evolutionary trends for subtribe Orchidinae with special emphasis on pollination systems. -

Orchids of Lakeland

a field guide to OrchidsLakeland Provincial Park, Provincial Recreation Area and surrounding region Written by: Patsy Cotterill Illustrated by: John Maywood Pub No: I/681 ISBN: 0-7785-0020-9 Printed 1998 Sepal Sepal Petal Petal Seed Sepal Lip (labellum) Ovary Finding an elusive (capsule) orchid nestled away in Sepal the boreal forest is a Scape thrilling experience for amateur and Petal experienced naturalists alike. This type Petal of recreation has become a passion for Column some and, for many others, a wonder- ful way to explore nature and learn Ovary Sepal (capsule) more about the living world around us. Sepal But, we also need to be careful when Lip (labellum) looking at these delicate plants. Be mindful of their fragile nature... keep Spur only memories and take only photo- graphs so that others, too, can enjoy. Corm OrchidsMany people are surprisedin Alberta to learn that orchids grow naturally in Alberta. Orchids are typically associated with tropical rain forests (where indeed, many do grow) or flower-shop purchases for special occasions, exotic, expensive and highly ornamental. Wild orchids in fact are found world-wide (except in Antarctica). They constitute Roots Tuber the second largest family of flowering plants (the Orchidaceae) after the Aster family, with upwards of 15,000 species. In Alberta, there are 26 native species. Like all Roots orchids from north temperate regions, these are terrestrial. They grow in the ground, in contrast to the majority of rain forest species which are epiphytes, that is, they grow attached to trees for support but do not derive nourishment from them. -

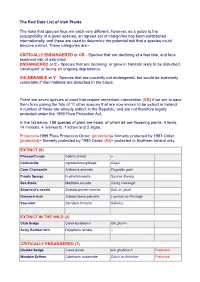

The Red Data List of Irish Plants

The Red Data List of Irish Plants The risks that species face are each very different, however, as a guide to the susceptibility of a given species, an agreed set of categories has been established internationally, and these are used to determine the potential risk that a species could become extinct. These categories are:- CRITICALLY ENDANGERED or CR - Species that are declining at a fast rate, and face imminent risk of extinction. ENDANGERED or E - Species that are declining, or grow in habitats likely to be disturbed, 'developed' or facing an ongoing degradation. VULNERABLE or V - Species that are currently not endangered, but would be extremely vulnerable if their habitats are disturbed in the future. There are seven species of plant that require immediate intervention (CR) if we are to save them from joining the fate of 11 other species that are now known to be extinct in Ireland. A number of these are already extinct in the Republic, and are not therefore legally protected under the 1999 Flora Protection Act. In the list below, 188 species of plant are listed, of which 64 are flowering plants, 4 ferns, 14 mosses, 4 liverworts, 1 lichen and 2 algae. Protected=1999 Flora Protection Order; (protected)= formerly protected by 1987 Order; {protected}= formerly protected by 1980 Order; (NI)= protected in Northern Ireland only. EXTINCT (9) Pheasant's-eye Adonis annua -- Corncockle Agrostemma githago Cogal Corn Chamomile Anthemis arvensis Fíogadán goirt Purple Spurge Euphorbia peplis Spuirse dhearg Sea Stock Matthiola sinuata Tonóg chladaigh -

Click to View .Pdf of This Issue

JJoouurrnnaall of the HHAARRDDYY OORRCCHHIIDD SSOOCCIIEETTYY Vol. 6 No. 2 (52) April 2009 JOURNAL of the HARDY ORCHID SOCIETY Vol. 6 No. 2 (52) April 2009 The Hardy Orchid Society Our aim is to promote interest in the study of Native European Orchids and those from similar temperate climates throughout the world. We cover such varied aspects as field study, cultivation and propagation, photography, taxonomy and systematics, and practical conservation. We welcome articles relating to any of these subjects, which will be considered for publication by the editorial committee. Please send your submissions to the Editor, and please structure your text according to the “Advice to Authors” (see website, January 2004 Journal, Members’ Handbook or contact the Editor). Views expressed in journal articles are those of their author(s) and may not reflect those of HOS. The Hardy Orchid Society Committee President: Prof. Richard Bateman, Jodrell Laboratory, Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 3DS Chairman & Field Meeting Co-ordinator: David Hughes, Linmoor Cottage, Highwood, Ringwood, Hants., BH24 3LE [email protected] Vice-Chairman: Celia Wright, The Windmill, Vennington, Westbury, Shrewsbury, Shropshire, SY5 9RG [email protected] Secretary (Acting): Alan Leck, 61 Fraser Close, Deeping St. James, Peterborough, PE6 8QL [email protected] Treasurer: Iain Wright, The Windmill, Vennington, Westbury, Shrewsbury, Shropshire, SY5 9RG [email protected] Membership Secretary: Celia Wright, The Windmill, Vennington, Westbury, -

Handbook a “Improving the Availability of Data and Information

Improving the availability of data and information on species, habitats and sites Focus Area A Handbook on the application of existing scientific approaches, methods, tools and knowledge for a better implementation of the Birds and Habitat Directives Environment FOCUS AREA A IMPROVING THE AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND i INFORMATION ON SPECIES, HABITATS AND SITES Imprint Disclaimer This document has been prepared for the European Commis- sion. The information and views set out in the handbook are Citation those of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect the Schmidt, A.M. & Van der Sluis, T. (2021). E-BIND Handbook (Part A): Improving the availability of data and official opinion of the Commission. The Commission does not information on species, habitats and sites. Wageningen Environmental Research/ Ecologic Institute /Milieu Ltd. guarantee the accuracy of the data included. The Commission Wageningen, The Netherlands. or any person acting on the Commission’s behalf cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information Authors contained therein. Lead authors: This handbook has been prepared under a contract with the Anne Schmidt, Chris van Swaay (Monitoring of species and habitats within and beyond Natura 2000 sites) European Commission, in cooperation with relevant stakehold- Sander Mücher, Gerard Hazeu (Remote sensing techniques for the monitoring of Natura 2000 sites) ers. (EU Service contract Nr. 07.027740/2018/783031/ENV.D.3 Anne Schmidt, Chris van Swaay, Rene Henkens, Peter Verweij (Access to data and information) for evidence-based improvements in the Birds and Habitat Kris Decleer, Rienk-Jan Bijlsma (Approaches and tools for effective restoration measures for species and habitats) directives (BHD) implementation: systematic review and meta- Theo van der Sluis, Rob Jongman (Green Infrastructure and network coherence) analysis).