Toward a Formal Model of Semantic Change: a Neo-Reichenbachian Approach to the Development of the Vedic Past Tense System*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa SALYA

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa SALYA PARVA translated by Kesari Mohan Ganguli In parentheses Publications Sanskrit Series Cambridge, Ontario 2002 Salya Parva Section I Om! Having bowed down unto Narayana and Nara, the most exalted of male beings, and the goddess Saraswati, must the word Jaya be uttered. Janamejaya said, “After Karna had thus been slain in battle by Savyasachin, what did the small (unslaughtered) remnant of the Kauravas do, O regenerate one? Beholding the army of the Pandavas swelling with might and energy, what behaviour did the Kuru prince Suyodhana adopt towards the Pandavas, thinking it suitable to the hour? I desire to hear all this. Tell me, O foremost of regenerate ones, I am never satiated with listening to the grand feats of my ancestors.” Vaisampayana said, “After the fall of Karna, O king, Dhritarashtra’s son Suyodhana was plunged deep into an ocean of grief and saw despair on every side. Indulging in incessant lamentations, saying, ‘Alas, oh Karna! Alas, oh Karna!’ he proceeded with great difficulty to his camp, accompanied by the unslaughtered remnant of the kings on his side. Thinking of the slaughter of the Suta’s son, he could not obtain peace of mind, though comforted by those kings with excellent reasons inculcated by the scriptures. Regarding destiny and necessity to be all- powerful, the Kuru king firmly resolved on battle. Having duly made Salya the generalissimo of his forces, that bull among kings, O monarch, proceeded for battle, accompanied by that unslaughtered remnant of his forces. Then, O chief of Bharata’s race, a terrible battle took place between the troops of the Kurus and those of the Pandavas, resembling that between the gods and the Asuras. -

Vedic Predecessors of One Type of Tantric Ritual

Cracow Indological Studies vol. XVI (2014) 10.12797/CIS.16.2014.16.06 Shingo Einoo [email protected] (University of Tokyo) Vedic Predecessors of One Type of Tantric Ritual SUMMARY: Verses 9–16 of the Parātriṃśikā prescribe a ritual application of the hr̥ dayabīja mantra ‘sauḥ’. In this case the mantra ‘sauḥ’ has different effects according to durations of the mental recitation of it. This is a very simple example of one type of tantric ritual where a limited number of mantras of a certain deity are used in different ways to accomplish a variety of efficacy by changing ritual elements of them. In Hindu tantric texts we find more similar cases. In the newest layer of Vedic texts such as the Ṛgvidhāna, Sāmavidhāna Brāhmaṇa and the Atharvavedapariśiṣṭa there are some similar examples of this kind. The Taittirīyasaṃhitā describes in two succeeding chapters various applications of two mantras called rāṣṭrabhr̥ t and devikāhavis respectively. In this paper I examine more Vedic examples and elucidate the basic idea underlying this type of ritual. KEYWORDS: Vedic ritual, Tantric ritual, ritual application, ritual variation 1. Introduction 1-0 Both Vedic studies and Tantric studies have their own vast fields of research, namely the corpus of Vedic and Tantric texts. Both areas have their own history of development and characteristics. It is there- fore not easy to have an intimate knowledge of both the Vedic and Tantric texts at the same time for one scholar. But by choosing some specific topics it may be possible to investigate Vedic and Tantric texts in some detail. -

MAN in NATURE Nature As Feminine

MAN IN NATURE Nature as Feminine Ancient Vision of Geopiety and Goddess Ecology Madhu Khanna The Feminine conceptualization of nature occupies very significant place in Indian religious history. The image of the earth as a goddess, known variously as Prthivi, Dharatimata, Jagadddhatri is ancient and all- pervasive. Almost all the geographical features of the natural environment are personified as goddesses. Mountains, caves, rocks, forests, trees, plants, healing herbs, rivers, streams, lakes were conceived of as potent symbols of feminine power, inherent in nature. From the Vedas down to the Puranas nature personifications are mediated through the symbol of the divine feminine. In the Rg Veda, for example, the crimson streak of day-break is portrayed as Usas, the Mistress of Dawn whose brilliant effulgence spreads out piercing the formless black abyss (RV, 10.127). Night and day are the two celestial sisters that bring rest and awakening to the world. In their lap, gods recline and enact their roles. The much celebrated mother of the gods, Aditi who claims as many as sixty hymns in the Vedas is the infinite and the womb of the cosmos. Goddesses such as, Kuhu, Sinivali, Anumati and Raka are lunar divinities symbolizing the waxing and waning of the lunar-cycle. The rivers Ganga, Yamuna and Sarasvati mentioned in the Vedas are goddesses who preside over the facundating waters of life. The hymn dedicated to Aranyani (RV, 10.146) or the forest goddesses (Vanadevis) celebrated the spirit of the forest and groves. They are joined by an innumerable number of goddesses who preside over village territories and specific sacred centres (Ksetradevis). -

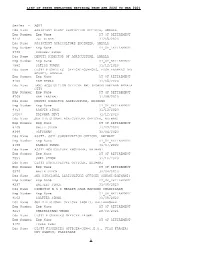

List of State Govt Employees Retiring Within One Year

LIST OF STATE EMPLOYEES RETIRING FROM APR 2020 TO MAR 2021 Series - AGRI Ddo Name ASSISTANT PLANT PROTECTION OFFICER, AMBALA Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 9312 JAI SINGH 31/05/2020 Ddo Name ASSISTANT AGRICULTURE ENGINEER, AMBALA Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 6738 SUKHDEV SINGH Ddo Name DEPUTY DIRECTOR OF AGRICULTURE, AMBALA Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 7982 SATISH KUMAR 31/12/2020 Ddo Name DISTT FISHERIES OFFICER-CUM-CEO, FISH FARMERS DEV AGENCY, AMBALA Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 8166 RAM NIWAS 31/05/2020 Ddo Name LAND ACQUISITION OFFICER PWD (POWER)HARYANA AMBALA CITY Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 8769 RAM PARSHAD 31/08/2020 Ddo Name DEPUTY DIRECTOR AGRICULTURE, BHIWANI Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 9753 RANVIR SINGH 31/12/2020 10203 KRISHNA DEVI 31/12/2020 Ddo Name SUB DIVISIONAL AGRICULTURE OFFICER, BHIWANI Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 8105 DALIP SINGH 31/07/2020 8399 SATYAWAN 30/04/2020 Ddo Name ASSTT. SOIL CONSERVATION OFFICER, BHIWANI Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 6799 RAMESH KUMAR 31/07/2020 Ddo Name ASSTT AGRICULTURE ENGINEER, BHIWANI Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 7593 SHER SINGH 31/10/2020 Ddo Name DISTT HORTICULTURE OFFICER, BHIWANI Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 6576 WAZIR SINGH 30/04/2020 Ddo Name SUB DIVSIONAL AGRICULTURE OFFICER SIWANI(BHIWANI) Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 8237 BALJEET SINGH 31/05/2020 Ddo Name DIRECTOR E S I HEALTH CARE HARYANA CHANDIGARH Emp Number Emp Name DT_OF_RETIREMENT 8562 CHATTER SINGH 30/09/2020 Ddo Name SUB DIVISIONAL -

Sri Arobindo Glossary to the Record of Yoga

Glossary to the Record of Yoga Introductory Note Status. Work on this glossary is in progress. Some definitions are provisional and will be revised before the glossary is published. Scope. Most words from languages other than English (primarily San- skrit), and some English words used in special senses in the Record of Yoga, are included. Transliteration. Words in italics are Sanskrit unless otherwise indi- cated. Sanskrit words are spelled according to the standard interna- tional system of transliteration. This has been adopted because the same Sanskrit word is often spelled in more than one way in the text. The spellings that occur in the text, if they differ from the transliter- ation (ignoring any diacritical marks over and under the letters), are mentioned in parentheses. The sounds represented by c, r.,ands´ or s. in the standard transliteration are commonly represented by “ch”, “ri”, and “sh” in the anglicised spellings normally used in the Record of Yoga. Order. All entries, regardless of language, are arranged in English al- phabetical order. Words and phrases are alphabetised letter by letter, disregarding diacritics, spaces and hyphens. Compounds and phrases. A compound or phrase composed of words that do not occur separately in the text is normally listed as a unit and the words are not defined individually. Compound expressions consisting of words that also occur by themselves, and thus are defined separately, are listed in the glossary only if they occur frequently or have a special significance. Definitions. The definition of each term is intended only as an aid to understanding its occurrences in the Record of Yoga. -

Land Tenures in India, Part XI-A

~CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME I I N.D I A PART XI-A ( i ) LAND TENURES IN INDIA A "iOK MITRA Regist,.ar GenerAl7 India ex-officio Census Commissioner; India & BALDEV R.AJ KALRA llesea ch ()~cer Office of the . RegIstrar General, India CENSUS OF INDIA 1961-UNION PUBLICATIONS PA'RT I G~neral Report on the Census, sub-divided into three sub-parts viz. Part I-A General Report Part l-A(i) (Tc:;xt) Levels of Regional Development in India Part I-A(i) (Tables) Levels of Regional Development in India Part I-B Vital Statistics of the decade Part I-C Subsidiary Tables PART II Census Tables of Population, sub-divided into: Part II-A(i).. General Population Tables Part II-A(ii) Union 'Primary Census Abstracts Part I1-B(i} GeneraJ Economic Tables (H-I to B-IV) Part II-B{ii) General Economic Tables (B-V)' Part II-B(iii) General Economic Tableq (B-VI to B-IX) Part I1-C(i} Social and Cultural Tables Part II-C(i i) Language Tables Part I1-C(iii) Migration Tables (D-I toTI-V) Part II-C(iv) Migration Tables (D-VI) PART III Part In(i) Householr.l Economic Tables (14 States) Pa(t IIT(ii) House~old Economic Tables (India, Uttar Pradesh & Union Territories) 'f: PART IV Part IV-A(i) Housing Report Part IV-A(ii) Report on Industrial Establishments Palt IV-A(iii) House Types & Village Layouts Part IV-B Housing & Establishment Tables PART V Spec~al Tables of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes and Ethnographic Notes, sub· divided into two sub--parts viz.- ' Part V-A(i) Special Tables for SCheduled Castes Part V-A(ii) Special Tables for Scheduled Tribes Part V-B Ethnographic Notes PART VI Village Survey Monograph PART VII - Monographs on Rural Crops ~urvey and list of Fairs and Festivals Part VII-A Handicraft Survey Monograph Part VlI-B Fairs and Festivals PART VIII Administration Report Part VIII-A Administration Report (Enumeration) Part VIII-B Administration Report (Tabulation) Not for sale' ,i PART IX Census Atlas Volume PART X Special Report on fities with population of one million and gvet, PART XI Special Surveys CONTENTS A- FOREWOltD ... -

Hymn to Anumati the Divine Grace

B H A V A N Hymn to Anumati The Divine Grace (Atharva Veda VII.20) Original text with Transliteration, English and German Translations and Notes based on the writings of Sri Aurobindo Nishtha February 2007 1 ‘Nishtha’ is the Sanskrit name of Siegfried Müller. He was born in Germany in 1956 and has lived in Auroville since 1981. This booklet presents a first sample of the research which he has been pursuing for many years, and which has recently been adopted as a project for support by the Government of India (HRD Ministry) through SAIIER. Nishtha was born into an ordinary farming family in rural Bavaria and did not receive a scholarly education. When he settled in Auroville he worked first as a gardener, and more recently as a music teacher. But he had been drawn to India by his soul’s call, which brought him to Sri Aurobindo, to Auroville, and to the Veda, which Sri Aurobindo has characterised as the root of all lndian spirituality. Deeply attracted to the Sanskrit language, in his studies Nishtha followed the clue given by Sri Aurobindo to the psychological symbolism of the world’s most ancient scriptures. This led him to attempt to translate, first into German and later into English, some of the Vedic hymns not translated or commented upon by Sri Aurobindo. In his renderings Nishtha has tried to bring out the profounder spiritual significance of the hymns, in a way that makes them accessible to contemporary readers. In his studies and his work Nishtha has been very much helped and supported in recent years by Vladimir Iatsenko. -

JNAC ACCP.Xlsx

BLOCK- JAMSHEDPUR (NAC) Accepted List जाँच ितवेदन के आधार पर सुपा पाये गये आवेदक परवार मुख क ाथिमकता सूची Acknowledgeme Family Requested Accept/ Sl. No. Family Head Catogory Dealer name REMARKS nt No. Count Mobile Reject 1 3570129995 LAKHI DEVI 2 8092248682 WIDOW NIMAN EKKA Accepted 2 3570133269 BEHULA BHUIYA 2 8797406136 WIDOW MAMTA BHUIYA Accepted 3 3570134226 SHIBANI DEVI 4 9308581162 WIDOW MAHESH SAW ONE Accepted 4 3570136945 Tara Devi 1 8674979473 WIDOW MAMTA BHUIYA Accepted 5 3570140159 ANITA SRIVASTAVA 3 6207048147 WIDOW MAHESH SAW ONE Accepted 6 3570141491 KULDEEP KAUR 3 6204690049 WIDOW BINOD RAJAK Accepted 7 3570142128 Inderjit Kour 4 8789048473 WIDOW SATENDRA KUMAR Accepted 8 3570142213 RENU 1 9122117528 WIDOW SHANKAR JHA Accepted 9 3570142886 SAVINDER KOUR 3 7033889610 WIDOW MAHESH SAW ONE Accepted 10 3570143446 UMA DEVI 2 7870305078 WIDOW MAHESH SAW ONE Accepted 11 3570143793 SIKHA BHATTACHARJEE 2 7209526640 WIDOW MAHESH SAW ONE Accepted 12 3570144071 KUMARI NIDHI 3 6204930114 WIDOW BINOD RAJAK Accepted 13 3570145956 POONAM SINGH 3 8210293283 WIDOW MAHESH SAW ONE Accepted 14 3570146238 hira jhari devi 3 7520288568 WIDOW BINOD RAJAK Accepted 15 3570148206 RANJANA MALLICK 3 8434456140 WIDOW MAHESH SAW ONE Accepted 16 3570160154 SARITA DEVI 3 6299769083 WIDOW BINOD RAJAK Accepted 17 3570161213 CHAPOLA MAHATO 2 7070355988 WIDOW BANSI SAO Accepted 18 3570162556 NIBHA DAS 3 9905976901 WIDOW BANSI SAO Accepted 19 3570163497 Sadhna Devi 2 6206052908 WIDOW JAY NARAYAN TIWARY Accepted 20 3570164215 BALBIR KAUR 3 9431303584 WIDOW BINOD -

ESSENCE of TAITTIRIYA ARANYAKA Part 1

ESSENCE OF TAITTIRIYA ARANYAKA Part 1 ( KRISHNA YAJURVEDA) BY V. D. N. RAO 1 Compiled, composed and interpreted by V.D.N.Rao, former General Manager, India Trade Promotion Organisation, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India, now at Chennai. Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu Purana, Matsya Purana, Varaha Purana, Kurma Purana, Vamana Purana, Narada Purana, Padma Purana; Shiva Purana, Linga Purana, Skanda Purana, Markandeya Purana, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma Purana, Brahma Vaivarta Purana, Agni Purana, Bhavishya Purana, Nilamata Purana; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama: a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri; b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata; c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda- Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers -Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu - Dharma Bindu - Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana-Essence of Paraashara Smriti Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima Essence of Upanishads : Brihadaranyaka , Katha, Tittiriya, Isha, Svetashwara of Yajur Veda- Chhandogya and Kena of Saama Veda-Atreya and Kausheetaki of Rig Veda-Mundaka, Mandukya and Prashna of Atharva Veda ; Also ‘Upanishad Saaraamsa’ (Quintessence of Upanishads) Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata- Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti Essence of Brahma Sutras Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Also Essence of Knowledge of Numbers Essence -

The Cosmology of the Rigveda : an Essay

r THE COSMOLOGY OF THE BIGVEDA, THE COSMOLOGY OF THE RIGVEDA, AN ESSAY H, W, WALLIS, M,A II GONVILLE AND CAIUS COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE. tfj trustees, WILLIAMS AND NORGATE, 14, HENRIETTA STREET, COVENT GARDEN, LONDON; AND 20, SOUTH FREDERICK STREET, EDINBURGH. 1887. HERTFORD ; PRINTED BY STEPHEN AUSTIN AND SON> PREFACE. THE object of this essay is not so much to present a complete picture of the Cosmology of the Eigveda, as to supply the material from which such a picture may be drawn. The writer has endeavoured to leave no strictly cosmological passage without a reference, and to add references to illustrative passages where they appeared to indicate the direction in which an explanation may be sought. In order to avoid any encumbrance of the notes by superfluous matter, references which are easily accessible in other books, such as Grassmann s Lexicon, are omitted, and those references which are intended to substantiate statements which are not likely to be the subject of doubt, are reduced to the smallest number possible. The isolation of the Eigveda vi Preface. is justified on linguistic grounds. On the other hand, the argument which is drawn from the Atharvaveda in the Introduction is based on the fact, attested by the internal character of that collection and by tradition, that the Atharvaveda lies apart from the stream of Brahmanic development : on the testimony of residents in India to the superstitious character of modern Hindoos : and on the striking similarity of the charms of the Atharvaveda to those of European nations. If, as eems most probable, the cosmological passages and hymns of the Eigveda are to be classified with the latest compositions in the collection, the conceptions with which the essay deals must be regarded as belonging to the latest period represented in the Eigveda, when the earlier hymns were still on the lips of priests whose language did not differ materially in construc tion from that contained in the hymns which they recited. -

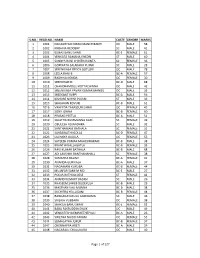

S.No. Regd.No. Name Caste Gender Marks 1 1001

S.NO. REGD.NO. NAME CASTE GENDER MARKS 1 1001 NAGASHYAM KIRAN MANCHIKANTI OC MALE 58 2 1002 KRISHNA REDDERY SC MALE 41 3 1003 ELMAS BANU SHAIK BC-E FEMALE 61 4 1004 VENKATA RAMANA KHEDRI ST MALE 60 5 1005 SANDYA RANI CHINTHAKUNTA SC FEMALE 36 6 1006 GOPINATH SALAKARU PUJARI SC MALE 28 7 1007 SREENIVASA REDDY GOTLURI OC MALE 78 8 1008 LEELA RANI B BC-A FEMALE 57 9 1009 RADHIKA KONDA OC FEMALE 30 10 1010 SREEDHAR M BC-D MALE 68 11 1011 CHANDRAMOULI KOTTACHINNA OC MALE 42 12 1012 SREENIVASA PAVAN KUMAR MANGU OC MALE 35 13 1013 SREEKANT SUPPI BC-A MALE 56 14 1014 KISHORE NAYAK PUJARI ST MALE 39 15 1015 SHAJAHAN KOVURI BC-B MALE 61 16 1016 VAHEEDA TABASSUM SHAIK OC FEMALE 45 17 1017 SONY JONNA BC-B FEMALE 60 18 1018 PRASAD PEETLA BC-A MALE 51 19 1019 SUJATHA BUMMANNA GARI SC FEMALE 49 20 1020 OBULESH ADIANDHRA SC MALE 32 21 1021 SANTHAMANI BATHALA SC FEMALE 31 22 1022 SARASWATHI GOLLA BC-D FEMALE 47 23 1023 LAVANYA GAJULA OC FEMALE 55 24 1024 SATEESH KUMAR MAHESWARAM BC-B MALE 38 25 1025 KRANTHI NALLAGATLA BC-B FEMALE 33 26 1026 RAVI KUMAR BATHALA BC-B MALE 68 27 1027 ADI LAKSHMI BANTHANAHALL SC FEMALE 38 28 1028 SAMATHA BALIMI BC-A FEMALE 41 29 1030 ANANDA GURIKALA BC-A MALE 37 30 1031 NAGAMANI KURUBA BC-B FEMALE 44 31 1032 MUJAFAR SAMI M MD BC-E MALE 27 32 1033 POOJA RATHOD DESE ST FEMALE 42 33 1034 ANAND KUMART BADIGI SC MALE 26 34 1035 KHASEEM SAHEB DUDEKULA BC-B MALE 29 35 1036 MASTHAN VALI MUNNA BC-B MALE 38 36 1037 SUCHITRA YELLUGANI BC-B FEMALE 44 37 1038 RANGANAYAKULU GUDIDAMA SC MALE 46 38 1039 SAILAJA VUBBARA OC FEMALE 38 39 1040 SHAKILA BANU SHAIK BC-E FEMALE 52 40 1041 BABA FAKRUDDIN SHAIK OC MALE 49 41 1042 VENKATESH DEMAKETHEPALLI BC-A MALE 26 42 1043 SWETHA NAIDU PAKAM OC FEMALE 55 43 1044 SUMALATHA JUKUR BC-B FEMALE 37 44 1047 CHENNAPPA ARETI BC-A MALE 29 45 1048 NAGARAJU CHALUKURU OC MALE 40 Page 1 of 127 S.NO. -

Glossary to the Record of Yoga

Glossary to the Record of Yoga Introductory Note Status. Work on this glossary is in progress. Some definitions are provisional and will be revised before the glossary is published. Scope. Most words from languages other than English (primarily San- skrit), and some English words used in special senses in the Record of Yoga, are included. Transliteration. Words in italics are Sanskrit unless otherwise indi- cated. Sanskrit words are spelled according to the standard interna- tional system of transliteration. This has been adopted because the same Sanskrit word is often spelled in more than one way in the text. The spellings that occur in the text, if they differ from the transliter- ation (ignoring any diacritical marks over and under the letters), are mentioned in parentheses. The sounds represented by c, r.,ands´ or s. in the standard transliteration are commonly represented by “ch”, “ri”, and “sh” in the anglicised spellings normally used in the Record of Yoga. Order. All entries, regardless of language, are arranged in English al- phabetical order. Words and phrases are alphabetised letter by letter, disregarding diacritics, spaces and hyphens. Compounds and phrases. A compound or phrase composed of words that do not occur separately in the text is normally listed as a unit and the words are not defined individually. Compound expressions consisting of words that also occur by themselves, and thus are defined separately, are listed in the glossary only if they occur frequently or have a special significance. Definitions. The definition of each term is intended only as an aid to understanding its occurrences in the Record of Yoga.