Language Policy in the Dutch Colony: on Sundanese in the Dutch East Indies *

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Arxiv:2011.02128V1 [Cs.CL] 4 Nov 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4203/arxiv-2011-02128v1-cs-cl-4-nov-2020-234203.webp)

Arxiv:2011.02128V1 [Cs.CL] 4 Nov 2020

Cross-Lingual Machine Speech Chain for Javanese, Sundanese, Balinese, and Bataks Speech Recognition and Synthesis Sashi Novitasari1, Andros Tjandra1, Sakriani Sakti1;2, Satoshi Nakamura1;2 1Nara Institute of Science and Technology, Japan 2RIKEN Center for Advanced Intelligence Project AIP, Japan fsashi.novitasari.si3, tjandra.ai6, ssakti,[email protected] Abstract Even though over seven hundred ethnic languages are spoken in Indonesia, the available technology remains limited that could support communication within indigenous communities as well as with people outside the villages. As a result, indigenous communities still face isolation due to cultural barriers; languages continue to disappear. To accelerate communication, speech-to-speech translation (S2ST) technology is one approach that can overcome language barriers. However, S2ST systems require machine translation (MT), speech recognition (ASR), and synthesis (TTS) that rely heavily on supervised training and a broad set of language resources that can be difficult to collect from ethnic communities. Recently, a machine speech chain mechanism was proposed to enable ASR and TTS to assist each other in semi-supervised learning. The framework was initially implemented only for monolingual languages. In this study, we focus on developing speech recognition and synthesis for these Indonesian ethnic languages: Javanese, Sundanese, Balinese, and Bataks. We first separately train ASR and TTS of standard Indonesian in supervised training. We then develop ASR and TTS of ethnic languages by utilizing Indonesian ASR and TTS in a cross-lingual machine speech chain framework with only text or only speech data removing the need for paired speech-text data of those ethnic languages. Keywords: Indonesian ethnic languages, cross-lingual approach, machine speech chain, speech recognition and synthesis. -

Sundanese Language Survival Among Indonesian Diaspora Families in Melbourne, Australia

Ahmad Bukhori Muslim, Sundanese Language Survival Among Indonesian Diaspora Families SUNDANESE LANGUAGE SURVIVAL AMONG INDONESIAN DIASPORA FAMILIES IN MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA Ahmad Bukhori Muslim Indonesia University of Education [email protected] Abstract Most migrant families living anywhere in the world, are concerned with maintaining their ethnic language, in order to sustain a sense of belonging to the country of their origin and enable extended family harmony. This study explores the survival of Sundanese language among eight Indonesian families of West Java origin (Sundanese speakers) living permanently in Melbourne, Australia. Most of these families migrated to Australia in the 1950s as Colombo Plan scholars and unskilled labourers. Semi-structured interviews and home observations showed that, despite believing in the importance of Sundanese language in their diasporic life, speaking Sundanese is the only practice that most of the participating parents, can do to maintain their language, alongside Bahasa Indonesia and English, to show they belong to the Sundanese culture. However, Sundanese language levels of politeness limit its use among their Australia-born second generation, making this ethnic language unlikely to survive. The young people only understand and copy a few routine words of greetings and short instructions. The study also suggests that the parents needed to be accommodative in order to maintain the Sundanese language by combining it with English and Bahasa Indonesia. Key words: Sundanese language maintenance, Indonesian diaspora, parental advice and values INTRODUCTION Like other local ethnic groups of Historically most Sundanese people Indonesia, a lot of Sundanese people migrate have lived in the Western part of Java Island, to various overseas countries, including long before the independence of Indonesia. -

Maybe English First and Then Balinese and Bahasa Indonesia“: a Case of Language Shift, Attrition, and Preference

Indonesian Journal of English Language Teaching, 11(1), May 2016, pp. 81-99 —0aybe English first and then Balinese and Bahasa Indonesia“: A case of language shift, attrition, and preference Siana Linda Bonafix* LembagaPengembanganProfesi, UniversitasTaruma Negara, Jakarta Christine Manara Program PascaSarjana, LinguistikTerapanBahasaInggris, UniversitasKatolik Indonesia Atma Jaya, Jakarta Abstract This small-scale Tualitative study aims to explore the participants‘ view of languages acquired, learned, and used in their family in an Indonesian context. The two participants were Indonesians who came from multilingual and mixed-cultural family background. The study explores three research questions: 1) What are the languages acquired (by the participants‘ family members), co- existed, and/or shift in the family of the two speakers? 2) What factors affect the dynamicity of these languages? 3) How do the participants perceive their self-identity? The qualitative data were collected using semi-structured and in-depth interviews. The interviews were audio-taped and transcribed to be analyzed using thematic analysis. The study detects local language shift to Indonesian from one generation to the next in the participants‘ family. The data also shows several factors for valorizing particular languages than the others. These factors include socioeconomic factor, education, frequency of contact, areas of upbringing (rural or urban) and attitude towards the language. The study also reveals that both participants identify their self-identity based on the place where they were born and grew up instead of their linguistic identity. Keywords: bilingualism, bilinguality, language dynamics, valorization, mix-cultural families Introduction Indonesia is a big multicultural and multilingual country. It is reported in 2016 that the population of the country is 257 million (BadanPusatStatistik, National StatisticsBureau). -

Coping with Religious-Based Segregation and Discrimination: Efforts in an Indonesian Context

HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies ISSN: (Online) 2072-8050, (Print) 0259-9422 Page 1 of 8 Original Research Coping with religious-based segregation and discrimination: Efforts in an Indonesian context Author: The aim of this article was to describe and analyse religious-based segregation and 1 Rachel Iwamony discrimination in the Moluccas and West Java, two places in Indonesia. Generally, people live Affiliation: peacefully side by side. However, in some places, social conflicts occur. By means of interview 1Faculty of Theology, and focus group discussion, the researcher observed and concluded that the main cause of the Indonesia Christian University conflicts was religious discrimination. In Moluccas, Christians and Muslims live separately. In in the Moluccas, Ambon, coping with that problem, the local leaders keep trying to talk directly with one another and to Indonesia engage in social acts together. Nevertheless, there are still some indigenous people experiencing Corresponding author: religious discrimination. One of them is Sunda Wiwitan. Their access to acquire birth Rachel Iwamony, certificates has been hindered. Consequently, they have limited access to public services, iwamonyrachel07@yahoo. including education and healthcare. However, their religious principles encourage them to be com compassionate towards others and prohibit them from causing danger to others. Dates: Received: 30 Apr. 2020 Contribution: Religious understanding and reconciliation have become important topics in Accepted: 28 Aug. 2020 the midst of religious conflict. This article contributes to promote religious reconciliation Published: 18 Nov. 2020 through some very simple and practical ways that reflect the core of religious teachings. How to cite this article: Keywords: Religion; Segregation; Discrimination; Violence; Non-violence; Indonesian Iwamony, R., 2020, ‘Coping religious life. -

Discovering the 'Language' and the 'Literature' of West Java

Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 34, No.1, June 1996 Discovering the 'Language' and the 'Literature' of West Java: An Introduction to the Formation of Sundanese Writing in 19th Century West Java* Mikihira MaRlYAMA** I The 'Language' Discovering the 'Language' An ethnicity (een volk) is defined by a language.i) This idea had come to be generally accepted in the Dutch East Indies at the beginning of the twentieth century. The prominent Sundanese scholar, Raden Memed Sastrahadiprawira, expressed it, probably in the 1920s, as follows: Basa teh anoe djadi loeloegoe, pangtetelana djeung pangdjembarna tina sagala tanda-tanda noe ngabedakeun bangsa pada bangsa. Lamoen sipatna roepa-roepa basa tea leungit, bedana bakat-bakatna kabangsaan oge moesna. Lamoen ras kabangsaanana soewoeng, basana eta bangsa tea oge lila-lila leungit. [Sastrahadiprawira in Deenik n. y.: 2] [The language forms a norm: the most evident and the most comprehensive symbols (notions) to distinguish one ethnic group from another. If the characteristics of a language disappear, the distinguishing features of an ethnicity will fade away as well. If an ethnicity no longer exists, the language of the ethnic group will also disappear in due course of time.] There is a third element involved: culture. Here too, Dutch assumptions exerted a great influence upon the thinking of the growing group of Sundanese intellectuals: a It occurred to me that I wanted to be a scholar when I first met the late Prof. Kenji Tsuchiya in 1980. It is he who stimulated me to write about the formation of Sundano logy in a letter from Jakarta in 1985. -

The Relationship Between Language and Architecture: a Case Study of Betawi Cultural Village at Setu Babakan, South Jakarta, Indonesia

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Vol. 5, No. 8; August 2015 The Relationship between Language and Architecture: A Case Study of Betawi Cultural Village at Setu Babakan, South Jakarta, Indonesia Agustin Rebecca Lakawa Language Centre, Trisakti University Faculty of Civil Engineering and Planning, Trisakti University Jl. Kyai Tapa No.1, Grogol, West Jakarta 11440 Indonesia Abstract Betawi language as the language of the people who occupied Jakarta and its surroundings is used to define ethnicity and provided cultural identity of Betawi people. This study reports on the relationship between language and architecture in terms of Betawi vernacular. To support the understanding and explanation about the topic, data gathered through observation and semi-structured interview at Betawi cultural village. The understanding about Betawi vernacular can best be replaced by the concepts of architecture in Betawi traditional houses. The study shows that the relationship between language and architecture can be seen in terms of its continuous dependability and relationship. The parts and sections of Betawi houses represent the openness towards outside and new influences, which accommodate creative and innovative forms added to Betawi houses. This openness can be traced in terms of language, which is represented in the form of having various borrowing words from other languages. The simplicity of Betawi house is the representation of the simplicity of Betawi language as can be seen in the form of grammatical features of the language. In sum, there is a clear relationship between Betawi language and architecture in terms of its simplicity, its openness, and its adaptability towards foreign influences. Keywords: Betawi language, Betawi architecture, adaptability, vernacular 1. -

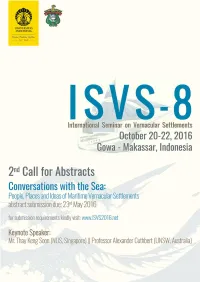

ISVS-8I Nternational

ABSTRACT COMPILATION I n t e r n a t i o n a l S e m i n a r o n V e r n a c u l a r ISVS-8Settlements 2016 Gowa Campus- Hasanuddin University, Makassar-INDONESIA, October 20th-22nd, 2016 International Seminar on Vernacular Settlements CONVERSATION WITH THE SEA:People, Place and Ideas of Maritime Vernacular Settlements October 20th–22nd, 2016, Gowa- Makassar, Indonesia Welcome to Makassar … We wish all participants will find this seminar intellectually beneficial as well as fascinating and looking forward to meeting you all again in future seminars ISVS-8 CONVERSATION WITH THE SEA People, Place and Ideas of Maritime Vernacular Settlements Seminar COMMITTEE Department of Architecture Hasanuddin University CONTENT Content ................................................................................................ i Seminar Schedule ................................................................................ vi Rundown Seminar ............................................................................. viii Parallel Session Schedule .................................................................... ix Abstract Compilation ........................................................................ xvii Theme: The Vernacular and the Idea of “Global” 1. Change in Vernacular Architecture of Goa: Influence of changing priorities from traditional sustainable culture to Global Tourism, by Barsha Amarendra and Amarendra Kumar Das ....................................... 1 2. Emper : Form, Function, And Meaning Of Terrace On Eretan Kulon Fisher -

Sundanese Language Level Detection Using Rule-Based Classification: Case Studies on Twitter

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 9, ISSUE 08, AUGUST 2020 ISSN 2277-8616 Sundanese Language Level Detection Using Rule-Based Classification: Case Studies On Twitter Ade Sutedi, Dede Kurniadi, Wiyoga Baswardono Abstract : Along with the history of the Sundanese tradition, language has an important role to show the existence of Sundanese culture, especially in Banten and West Java. Today, the use of Sundanese language are decreased due to a competition of regional languages with national languages even with foreign languages. In addition, the divergence of language in the society cause disparities between young people and older people. The native speaker are reduced due to social developments in society that are increasingly wide open. This issue becomes popular in the last decade due to the death of language especially for regional language. To discover the existence of Sundanese language in social media today, Twitter was used to analyze as a parameter that indicate the existence of a Sundanese language used by the people. The objectives of this research are: (1) to identified the existence of Sundanese language in social media; (2) to classify the word levels of Sundanese language used and comparing their levels to get the summary of characteristic of Sundanese language for every region. In this research, classification process taken from Sundanese vocabulary which divided into three levels: Ribaldry level (Loma), Standard level (Hormat ka sorangan), and Polite level (Hormat ka batur). Classification involves the word n-grams (unigram, bigram, and trigram) features with rule-based classification to determine Sundanese and non Sundanese language with their levels. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 178 1st International Conference of Innovation in Education (ICoIE 2018) The Role of Parents in Sundanese Language Preservation Dingding Haerudin Sundanese nd Culture Education Graduate School Indunesia University of Education Bangdung, Jawa Barat, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract—This paper presents one of the results of pressure in the study refers to speaking partner, who is the research on “A Need Analysis of Mother Tongue Program higher-ranking or older (Panicacci & Dewaele 2017). Development 2013.” The study aimed to describe the efforts of parents in the preservation of the Sundanese language as a To address the problems certainly requires the native language and a local language. The description of this cooperation of all parties, especially the family paper includes the use of Sundanese language in everyday environment (parents) and educational institutions. It is life at home and its surrounding environment; in important to expose knowledge and understanding of the communication with teachers at school; the importance of cultural richness embodied in language and literature, as a instilling manners of speaking (undak-usuk/unggah-ungguh) valuable treasure and universal source of local wisdom to children; the importance of Sundanese language teaching (Cornhill 2014). in schools; the importance of children learning local culture; the types of culture that children learn; the efforts of parents Therefore, this paper presents one of the results of to encourage children to learn the culture; and the opinion research on “A Need Analysis of Mother Tongue Program that the local language is used as the language of education Development 2013.” The one of the results is efforts of at the elementary level. -

A Grammar of Toba Batak Koninklijk Instituut Voor Taal-, Land- En Volkenkunde

A GRAMMAR OF TOBA BATAK KONINKLIJK INSTITUUT VOOR TAAL-, LAND- EN VOLKENKUNDE TRANSLATION SERIES 13 H. N. VAN DER TUUK A GRAMMAR OF TOBA BATAK Springer-Science+Business Media, B.V. 1971 This book is published under a grant from the Netherlands Ministry of Education and Sciences The original title was : TOBASCHE SPRAAKUNST in dienst en op kosten van het Nederlandsch Bijbelgenootschap vervaardigd door H. N. van der Tuuk Amsterdam Eerste Stuk (Klankstelsel) 1864 Tweede Stuk (De woorden als Zindeelen) 1867 The translation was made by Miss Jeune Scott-Kemball; the work was edited by A. Teeuw and R. Roolvink, with a Foreword by A. Teeuw. ISBN 978-94-017-6707-1 ISBN 978-94-017-6778-1 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-94-017-6778-1 CONTENTS page Foreword by A. Teeuw XIII Preface to part I XL Preface to part II . XLII Introduction XLVI PART I THE SOUND SYSTEM I. SCRIPT AND PRONUNCIATION 1. WTiting . 3 2. The alphabet . 3 3. Anak ni surat . 4 4. Pronunciation of the a 5 5. Pronunciation of thee 5 6. Pronunciation of the o . 6 7. The relationship of ·the consona.n.ts to each other 7 8. Fusion of vowels . 9 9. wortl boundary . 10 10. The pronunciation of ?? . 10 11. The nasals as closers before an edged consonant 11 12. The nasals as closeTs before h . 12 13. Douible s . 13 14. The edged consonants as closers before h. 13 15. A closer n before l, r and m 13 16. R as closer of a prefix 14 17. -

E. Van Zanten Allophonic Variation in the Production of Indonesian Vowels

E. van Zanten Allophonic variation in the production of Indonesian vowels In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 142 (1986), no: 4, Leiden, 427-446 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/26/2021 09:51:23PM via free access ELLEN VAN ZANTEN ALLOPHONIC VARIATION IN THE PRODUCTION OF INDONESIAN VOWELS 1. Introduction Grammars of the Indonesian language usually state that there is allo- phonic variation in vowel realization between open and closed syllables. It is also generally claimed that there is allophonic vowel harmony, with vowels in open syllables being realized as the high variant of the relevant phoneme (e.g. isi [isi]), whereas the low variant is found not only in closed syllables but also in open syllables which are followed by closed syllables with the same vowel in the same word (e.g. titik [tltlk]; cf. Macdonald 1976:15). There is no agreement in the literature as regards the vowel phonemes with respect to which this allophonic variation takes place. To mention some examples: Macdonald (1976) states that all Indonesian vowel phonemes exeept hl usually have two chief allophones, although in some areas each of the six vowels has only one pronuncation in all positions in the word (Macdonald 1976:14). According to Teeuw (1984: 9-10) allophonic variation occurs with /i, e, a, o/. To mention an extreme case: Ro'is (1985:11-13) states that allophonic variation occurs only with /i/and lal. In a study of Indonesian vowels spoken in isolation, we discovered considerable differences that could be related to the substrate language of the speakers (van Zanten and van Heuven 1984). -

Jurnal IJCS 2

Problem Solution in Cultural Differences Between Sundanese and non Sundanese Couple in Bandung by Using Intercultural Communication Christina Rochayanti Department of Communication Studies Faculty of Social and Political Sciences University of Pembangunan Nasional “Veteran” Yogyakarta, Indonesia Abstract Interethnic marriage means legal union of spouse from different ethnic group. It is a form of cultural background differences at interpersonal level (micro). Besides, starting their new marriage life, the couple must also adjust themselves respectively toward different cultural elements. The method of the research is interpretive-qualitative with symbolic interaction approach. Participants of the research were selected from those who have been through the process of cultural adjustment in interethnic marriage. Data was collected by deeply interviewing and observing 13 couples, Sundanese and non-Sundanese that have been married for more than 10 years and have children. Generally, the research shown that Sunda cultural and custom of couples’ ethnic identity difference formed a communication interethnic marriage patterns Sundanese and non Sundanese in Bandung. The results of the research were divided into three findings : firstly the communication patterns of interethnic marriage can be classified into; (1) dominant, (2) initiative, (3) combination, (4) adaptive, and (5) creative. Secondly, various pressures in the interethnic marriage life mainly caused by financial support for their extended family, different food appetite, life style and social comments. Thirdly, the interethnic couples can accommodate the differences in treating their children and interacting with their extended family. Keywords: Intercultural Communication, Interethnic Marriage, Ethnic Introduction Interethnic marriage is defined as a legal It is the culture which programmed us to union of spouse from the different ethnic groups.