Distribution and Classification of the Protected Areas and the 2000 Simplified a T L a N T I C O C E a N 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reporton the Rare Plants of Puerto Rico

REPORTON THE RARE PLANTS OF PUERTO RICO tii:>. CENTER FOR PLANT CONSERVATION ~ Missouri Botanical Garden St. Louis, Missouri July 15, l' 992 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Center for Plant Conservation would like to acknowledge the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and the W. Alton Jones Foundation for their generous support of the Center's work in the priority region of Puerto Rico. We would also like to thank all the participants in the task force meetings, without whose information this report would not be possible. Cover: Zanthoxy7um thomasianum is known from several sites in Puerto Rico and the U.S . Virgin Islands. It is a small shrub (2-3 meters) that grows on the banks of cliffs. Threats to this taxon include development, seed consumption by insects, and road erosion. The seeds are difficult to germinate, but Fairchild Tropical Garden in Miami has plants growing as part of the Center for Plant Conservation's .National Collection of Endangered Plants. (Drawing taken from USFWS 1987 Draft Recovery Plan.) REPORT ON THE RARE PLANTS OF PUERTO RICO TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements A. Summary 8. All Puerto Rico\Virgin Islands Species of Conservation Concern Explanation of Attached Lists C. Puerto Rico\Virgin Islands [A] and [8] species D. Blank Taxon Questionnaire E. Data Sources for Puerto Rico\Virgin Islands [A] and [B] species F. Pue~to Rico\Virgin Islands Task Force Invitees G. Reviewers of Puerto Rico\Virgin Islands [A] and [8] Species REPORT ON THE RARE PLANTS OF PUERTO RICO SUMMARY The Center for Plant Conservation (Center) has held two meetings of the Puerto Rlco\Virgin Islands Task Force in Puerto Rico. -

Sitios Arqueológicos De Ponce

Sitios Arqueológicos de Ponce RESUMEN ARQUEOLÓGICO DEL MUNICIPIO DE PONCE La Perla del Sur o Ciudad Señorial, como popularmente se le conoce a Ponce, tiene un área de aproximadamente 115 kilómetros cuadrados. Colinda por el oeste con Peñuelas, por el este con Juana Díaz, al noroeste con Adjuntas y Utuado, y al norte con Jayuya. Pertenece al Llano Costanero del Sur y su norte a la Cordillera Central. Ponce cuenta con treinta y un barrios, de los cuales doce componen su zona urbana: Canas Urbano, Machuelo Abajo, Magueyes Urbano, Playa, Portugués Urbano, San Antón, Primero, Segundo, Tercero, Cuarto, Quinto y Sexto, estos últimos seis barrios son parte del casco histórico de Ponce. Por esta zona urbana corren los ríos Bucaná, Portugués, Canas, Pastillo y Matilde. En su zona rural, los barrios que la componen son: Anón, Bucaná, Canas, Capitanejo, Cerrillos, Coto Laurel, Guaraguao, Machuelo Arriba, Magueyes, Maragüez, Marueño, Monte Llanos, Portugués, Quebrada Limón, Real, Sabanetas, San Patricio, Tibes y Vallas. Ponce cuenta con un rico ajuar arquitectónico, que se debe en parte al asentamiento de extranjeros en la época en que se formaba la ciudad y la influencia que aportaron a la construcción de las estructuras del casco urbano. Su arquitectura junto con los yacimientos arqueológicos que se han descubierto en el municipio, son parte del Inventario de Recursos Culturales de Ponce. Esta arquitectura se puede apreciar en las casas que fueron parte de personajes importantes de la historia de Ponce como la Casa Paoli (PO-180), Casa Salazar (PO-182) y Casa Rosaly (PO-183), entre otras. Se puede ver también en las escuelas construidas a principios del siglo XX: Ponce High School (PO-128), Escuela McKinley (PO-131), José Celso Barbosa (PO-129) y la escuela Federico Degetau (PO-130), en sus iglesias, la Iglesia Metodista Unida (PO-126) y la Catedral Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe (PO-127) construida en el siglo XIX. -

Monocotyledons and Gymnosperms of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Contributions from the United States National Herbarium Volume 52: 1-415 Monocotyledons and Gymnosperms of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands Editors Pedro Acevedo-Rodríguez and Mark T. Strong Department of Botany National Museum of Natural History Washington, DC 2005 ABSTRACT Acevedo-Rodríguez, Pedro and Mark T. Strong. Monocots and Gymnosperms of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. Contributions from the United States National Herbarium, volume 52: 415 pages (including 65 figures). The present treatment constitutes an updated revision for the monocotyledon and gymnosperm flora (excluding Orchidaceae and Poaceae) for the biogeographical region of Puerto Rico (including all islets and islands) and the Virgin Islands. With this contribution, we fill the last major gap in the flora of this region, since the dicotyledons have been previously revised. This volume recognizes 33 families, 118 genera, and 349 species of Monocots (excluding the Orchidaceae and Poaceae) and three families, three genera, and six species of gymnosperms. The Poaceae with an estimated 89 genera and 265 species, will be published in a separate volume at a later date. When Ackerman’s (1995) treatment of orchids (65 genera and 145 species) and the Poaceae are added to our account of monocots, the new total rises to 35 families, 272 genera and 759 species. The differences in number from Britton’s and Wilson’s (1926) treatment is attributed to changes in families, generic and species concepts, recent introductions, naturalization of introduced species and cultivars, exclusion of cultivated plants, misdeterminations, and discoveries of new taxa or new distributional records during the last seven decades. -

Evaluación De Los Recursos Forestales De Puerto Rico

Department of Natural and Environmental Resources GOVERNMENT OF PUERTO RICO Puerto Rico Statewide Assessment and Strategies for Forest Resources Acknowledgements Many people have contributed to this final edition of the Puerto Rico Statewide Assessment and Strategies for Forest Resources (PRSASFR) in a variety of ways. We gratefully acknowledge the efforts of all those who contributed to this document, through all its stages until this final version. Their efforts have resulted in a comprehensive, forward- looking strategy to keep Puerto Rico‘s forests as healthy natural resources and thriving into the future. Thanks go to the extensive efforts of the hard working staff of the Forest Service Bureau of the Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources (DNER), and the International Institute of Tropical Forestry (IITF), whose joint work have made this PRFASFR possible. Within the DNER, we also want to thank the Comprehensive Planning Area, in particular to its Acting Assistant Secretary Mr. José E. Basora Fagundo for devoting resources under his supervision exclusively for this task. Within ITTF, we want to highlight the immeasurable contribution of the restless editor Ms. Constance Carpenter, who always pushed us to strive for excellence. In addition, we want to thank the Southern Group of State Foresters for their grant supporting many of the maps enclosed and text in the initial stages of this document. We are also grateful to Geographic Consulting LLC, whose collaboration was made possible by sponsorship of IITF, for their wonderful editing work in the previous stages of the document. Thanks also go to particular DNER and IITF staff, to members of the State Technical Committee through its Forest and Wildlife Subcommittee, and to other external professionals, for their particular contributions to and their efforts bringing the PRSASFR together: Editing Contributors: Nicole Balloffet (USFS) Cristina Cabrera (DNER) Constance Carpenter (IITF) Geographic Consulting LLC Magaly Figueroa (IITF) Norma Lozada (DNER) José A. -

Protected Areas by Management 9

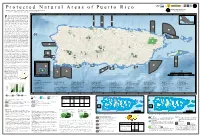

Unted States p Forest Department a Service DRNA of Agriculture g P r o t e c t e d N a t u r a l A r e a s o f P u e r to R i c o K E E P I N G C O M M ON S P E C I E S C O M M O N PRGAP ANALYSIS PROJECT William A. Gould, Maya Quiñones, Mariano Solórzano, Waldemar Alcobas, and Caryl Alarcón IITF GIS and Remote Sensing Lab A center for tropical landscape analysis U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, International Institute of Tropical Forestry . o c 67°30'0"W 67°20'0"W 67°10'0"W 67°0'0"W 66°50'0"W 66°40'0"W 66°30'0"W 66°20'0"W 66°10'0"W 66°0'0"W 65°50'0"W 65°40'0"W 65°30'0"W 65°20'0"W i R o t rotection of natural areas is essential to conserving biodiversity and r e u P maintaining ecosystem services. Benefits and services provided by natural United , Protected areas by management 9 States 1 areas are complex, interwoven, life-sustaining, and necessary for a healthy A t l a n t i c O c e a n 1 1 - 6 environment and a sustainable future (Daily et al. 1997). They include 2 9 0 clean water and air, sustainable wildlife populations and habitats, stable slopes, The Bahamas 0 P ccccccc R P productive soils, genetic reservoirs, recreational opportunities, and spiritual refugia. -

Bookletchart™ Bahía De Ponce and Approaches NOAA Chart 25683 a Reduced-Scale NOAA Nautical Chart for Small Boaters

BookletChart™ Bahía de Ponce and Approaches NOAA Chart 25683 A reduced-scale NOAA nautical chart for small boaters When possible, use the full-size NOAA chart for navigation. Published by the Channels.–The principal entrance is E of Isla de Cardona. A Federal project provides for a 600-foot-wide entrance channel 36 feet deep, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration then an inner channel 200-foot-wide 36 feet deep leading to an irregular National Ocean Service shaped turning basin, with a 950-foot turning diameter adjacent to the Office of Coast Survey municipal bulkhead. The entrance channel is marked by a 015° lighted range, lights, and www.NauticalCharts.NOAA.gov buoys; do not confuse the rear range light with the flashing red radio 888-990-NOAA tower lights back of it. A 0.2-mile-wide channel between Isla de Cardona and Las Hojitas is sometimes used by small vessels with local knowledge. What are Nautical Charts? Anchorages.–The usual anchorage is NE of Isla de Cardona in depths of 30 to 50 feet, although vessels can anchor in 30 to 40 feet NW of Las Nautical charts are a fundamental tool of marine navigation. They show Hojitas. A small-craft anchorage is NE of Las Hojitas in depths of 18 to 28 water depths, obstructions, buoys, other aids to navigation, and much feet. (See 110.1 and 110.255, chapter 2, for limits and regulations.) A more. The information is shown in a way that promotes safe and well-protected anchorage for small boats in depths of 19 to 30 feet is NE efficient navigation. -

Puerto Rico Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy 2005

Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy Puerto Rico PUERTO RICO COMPREHENSIVE WILDLIFE CONSERVATION STRATEGY 2005 Miguel A. García José A. Cruz-Burgos Eduardo Ventosa-Febles Ricardo López-Ortiz ii Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy Puerto Rico ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Financial support for the completion of this initiative was provided to the Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources (DNER) by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) Federal Assistance Office. Special thanks to Mr. Michael L. Piccirilli, Ms. Nicole Jiménez-Cooper, Ms. Emily Jo Williams, and Ms. Christine Willis from the USFWS, Region 4, for their support through the preparation of this document. Thanks to the colleagues that participated in the Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy (CWCS) Steering Committee: Mr. Ramón F. Martínez, Mr. José Berríos, Mrs. Aida Rosario, Mr. José Chabert, and Dr. Craig Lilyestrom for their collaboration in different aspects of this strategy. Other colleagues from DNER also contributed significantly to complete this document within the limited time schedule: Ms. María Camacho, Mr. Ramón L. Rivera, Ms. Griselle Rodríguez Ferrer, Mr. Alberto Puente, Mr. José Sustache, Ms. María M. Santiago, Mrs. María de Lourdes Olmeda, Mr. Gustavo Olivieri, Mrs. Vanessa Gautier, Ms. Hana Y. López-Torres, Mrs. Carmen Cardona, and Mr. Iván Llerandi-Román. Also, special thanks to Mr. Juan Luis Martínez from the University of Puerto Rico, for designing the cover of this document. A number of collaborators participated in earlier revisions of this CWCS: Mr. Fernando Nuñez-García, Mr. José Berríos, Dr. Craig Lilyestrom, Mr. Miguel Figuerola and Mr. Leopoldo Miranda. A special recognition goes to the authors and collaborators of the supporting documents, particularly, Regulation No. -

To See Our Puerto Rico Vacation Planning

DISCOVER PUERTO RICO LEISURE + TRAVEL 2021 Puerto Rico Vacation Planning Guide 1 IT’S TIME TO PLAN FOR PUERTO RICO! It’s time for deep breaths and even deeper dives. For simple pleasures, dramatic sunsets and numerous ways to surround yourself with nature. It’s time for warm welcomes and ice-cold piña coladas. As a U.S. territory, Puerto Rico offers the allure of an exotic locale with a rich, vibrant culture and unparalleled natural offerings, without needing a passport or currency exchange. Accessibility to the Island has never been easier, with direct flights from domestic locations like New York, Charlotte, Dallas, and Atlanta, to name a few. Lodging options range from luxurious beachfront resorts to magical historic inns, and everything in between. High standards of health and safety have been implemented throughout the Island, including local measures developed by the Puerto Rico Tourism Company (PRTC), alongside U.S. Travel Association (USTA) guidelines. Outdoor adventures will continue to be an attractive alternative for visitors looking to travel safely. Home to one of the world’s largest dry forests, the only tropical rainforest in the U.S. National Forest System, hundreds of underground caves, 18 golf courses and so much more, Puerto Rico delivers profound outdoor experiences, like kayaking the iridescent Bioluminescent Bay or zip lining through a canopy of emerald green to the sound of native coquí tree frogs. The culture is equally impressive, steeped in European architecture, eclectic flavors of Spanish, Taino and African origins and a rich history – and welcomes visitors with genuine, warm Island hospitality. Explore the authentic local cuisine, the beat of captivating music and dance, and the bustling nightlife, which blended together, create a unique energy you won’t find anywhere else. -

(A) PUERTO RICO - Large Scale Characteristics

(a) PUERTO RICO - Large scale characteristics Although corals grow around much of Puerto Rico, physical conditions result in only localized reef formation. On the north coast, reef development is almost non-existent along the western two-thirds possibly as a result of one or more of the following factors: high rainfall; high run-off rates causing erosion and silt-laden river waters; intense wave action which removes suitable substrate for coral growth; and long shore currents moving material westward along the coast. This coast is steep, with most of the island's land area draining through it. Reef growth increases towards the east. On the wide insular shelf of the south coast, small reefs are found in abundance where rainfall is low and river influx is small, greatest development and diversity occurring in the southwest where waves and currents are strong. There are also a number of submerged reefs fringing a large proportion of the shelf edge in the south and west with high coral cover and diversity; these appear to have been emergent reefs 8000-9000 years ago which failed to keep pace with rising sea levels (Goenaga in litt. 7.3.86). Reefs on the west coast are limited to small patch reefs or offshore bank reefs and may be dying due to increased sediment influx, water turbidity and lack of strong wave action (Almy and Carrión-Torres, 1963; Kaye, 1959). Goenaga and Cintrón (1979) provide an inventory of mainland Puerto Rican coral reefs and the following is a brief summary of their findings. On the basis of topographical, ecological and socioeconomic characteristics, Puerto Rico's coastal perimeter can be divided into eight coastal sectors -- north, northeast, southeast, south, southwest, west, northwest, and offshore islands. -

Hilton Ponce Golf & Casino Resort the Facts

B:25.5” T:25.25” S:24.85” HILTON PONCE GOLF & CASINO RESORT HILTON PONCE GOLF & CASINO RESORT PROPERTY MAP THE FACTS GROUND FLOOR • La Terraza CARIBE MEETING FACILITIES • El Bohio Pool & Sports Bar A B C • La Cava Restaurant • Recreational Facilities GROUND LEVEL • Swimming Pool & Spray Park BUSINESS • Mini Golf CENTER • Beach Access LOBBY LEVEL SECOND FLOOR C • Front Desk • Lobby B MEETING MEETING • Business Center PAVILION CENTER 2 CENTER 1 • Casino GRAN SALON A • Executive Ofces • Gift & Souvenir Shop • Video Games B:11.25” S:10.6” T:11” TO MAIN GATE TO MAIN GATE PARKING LOT BRID GE TO CO STA CA RI BE PARKING LOT MAIN ENTRANCE CONVENTION CENTER BUSINESS PRACTICE CENTER CASINO RANGE FRONT TENNIS COURTS PARKING DESK LOT Situated in a lush coconut grove on the southern tip AT A GLANCE of Puerto Rico, Hilton Ponce Golf & Casino Resort COSTA CARIBE • 255 spacious oceanfront guest rooms with private balconies or patios EAST TOWER GOLF & COUNTRY ofers relaxing experiences for business and leisure CLUB • Over 24,000ft² of indoor and outdoor Meeting and Function areas ponce.hilton.com guests alike. The resort ofers extensive meeting • Two swimming pools, open air Jacuzzi, kids playground, water slide and spray park WEST TOWER facilities, leisure activities and entertainment just • Casino with blackjack, roulette, slot machines, poker and more OCEAN TOWER POOL & BEACH 75 miles from Luis Muñoz Marin International Airport SERVICE CENTER • Championship golf with 32,000ft² oceanfront Clubhouse with pool PORTUGUES RIVER in San Juan (SJU) or 10 miles from Mercedita Airport HILTON PONCE and dining SALON VILLAS DEL MAR GOLF & CASINO RESORT in Ponce (PSE). -

Guide to Theecological Systemsof Puerto Rico

United States Department of Agriculture Guide to the Forest Service Ecological Systems International Institute of Tropical Forestry of Puerto Rico General Technical Report IITF-GTR-35 June 2009 Gary L. Miller and Ariel E. Lugo The Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture is dedicated to the principle of multiple use management of the Nation’s forest resources for sustained yields of wood, water, forage, wildlife, and recreation. Through forestry research, cooperation with the States and private forest owners, and management of the National Forests and national grasslands, it strives—as directed by Congress—to provide increasingly greater service to a growing Nation. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD).To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W. Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Authors Gary L. Miller is a professor, University of North Carolina, Environmental Studies, One University Heights, Asheville, NC 28804-3299. -

Declining Human Population but Increasing Residential Development Around Protected Areas in Puerto Rico

Biological Conservation 209 (2017) 473–481 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Biological Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/bioc Declining human population but increasing residential development around protected areas in Puerto Rico J. Castro-Prieto a,c,⁎, S. Martinuzzi b, V.C. Radeloff b,D.P.Helmersb,M.Quiñonesc,W.A.Gouldc a Department of Environmental Sciences, College of Natural Sciences, University of Puerto Rico, PO Box 23341, San Juan 00931-3341, Puerto Rico b SILVIS Lab, Department of Forest and Wildlife Ecology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1630 Linden Drive, Madison, WI 53706, USA c International Institute of Tropical Forestry, USDA Forest Service, 1201 Ceiba Street, Rio Piedras, 00926, Puerto Rico article info abstract Article history: Increasing residential development around protected areas is a major threat for protected areas worldwide, and Received 21 September 2016 human population growth is often the most important cause. However, population is decreasing in many regions Received in revised form 19 January 2017 as a result of socio-economic changes, and it is unclear how residential development around protected areas is Accepted 19 February 2017 affected in these situations. We investigated whether decreasing human population alleviates pressures from Available online xxxx residential development around protected areas, using Puerto Rico—an island with declining population—as a case study. We calculated population and housing changes from the 2000 to 2010 census around 124 protected Keywords: Human-population areas, using buffers of different sizes. We found that the number of houses around protected areas continued to Island increase while population declined both around protected areas and island-wide.