Declining Human Population but Increasing Residential Development Around Protected Areas in Puerto Rico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reporton the Rare Plants of Puerto Rico

REPORTON THE RARE PLANTS OF PUERTO RICO tii:>. CENTER FOR PLANT CONSERVATION ~ Missouri Botanical Garden St. Louis, Missouri July 15, l' 992 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Center for Plant Conservation would like to acknowledge the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and the W. Alton Jones Foundation for their generous support of the Center's work in the priority region of Puerto Rico. We would also like to thank all the participants in the task force meetings, without whose information this report would not be possible. Cover: Zanthoxy7um thomasianum is known from several sites in Puerto Rico and the U.S . Virgin Islands. It is a small shrub (2-3 meters) that grows on the banks of cliffs. Threats to this taxon include development, seed consumption by insects, and road erosion. The seeds are difficult to germinate, but Fairchild Tropical Garden in Miami has plants growing as part of the Center for Plant Conservation's .National Collection of Endangered Plants. (Drawing taken from USFWS 1987 Draft Recovery Plan.) REPORT ON THE RARE PLANTS OF PUERTO RICO TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements A. Summary 8. All Puerto Rico\Virgin Islands Species of Conservation Concern Explanation of Attached Lists C. Puerto Rico\Virgin Islands [A] and [8] species D. Blank Taxon Questionnaire E. Data Sources for Puerto Rico\Virgin Islands [A] and [B] species F. Pue~to Rico\Virgin Islands Task Force Invitees G. Reviewers of Puerto Rico\Virgin Islands [A] and [8] Species REPORT ON THE RARE PLANTS OF PUERTO RICO SUMMARY The Center for Plant Conservation (Center) has held two meetings of the Puerto Rlco\Virgin Islands Task Force in Puerto Rico. -

Monocotyledons and Gymnosperms of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Contributions from the United States National Herbarium Volume 52: 1-415 Monocotyledons and Gymnosperms of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands Editors Pedro Acevedo-Rodríguez and Mark T. Strong Department of Botany National Museum of Natural History Washington, DC 2005 ABSTRACT Acevedo-Rodríguez, Pedro and Mark T. Strong. Monocots and Gymnosperms of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. Contributions from the United States National Herbarium, volume 52: 415 pages (including 65 figures). The present treatment constitutes an updated revision for the monocotyledon and gymnosperm flora (excluding Orchidaceae and Poaceae) for the biogeographical region of Puerto Rico (including all islets and islands) and the Virgin Islands. With this contribution, we fill the last major gap in the flora of this region, since the dicotyledons have been previously revised. This volume recognizes 33 families, 118 genera, and 349 species of Monocots (excluding the Orchidaceae and Poaceae) and three families, three genera, and six species of gymnosperms. The Poaceae with an estimated 89 genera and 265 species, will be published in a separate volume at a later date. When Ackerman’s (1995) treatment of orchids (65 genera and 145 species) and the Poaceae are added to our account of monocots, the new total rises to 35 families, 272 genera and 759 species. The differences in number from Britton’s and Wilson’s (1926) treatment is attributed to changes in families, generic and species concepts, recent introductions, naturalization of introduced species and cultivars, exclusion of cultivated plants, misdeterminations, and discoveries of new taxa or new distributional records during the last seven decades. -

Evaluación De Los Recursos Forestales De Puerto Rico

Department of Natural and Environmental Resources GOVERNMENT OF PUERTO RICO Puerto Rico Statewide Assessment and Strategies for Forest Resources Acknowledgements Many people have contributed to this final edition of the Puerto Rico Statewide Assessment and Strategies for Forest Resources (PRSASFR) in a variety of ways. We gratefully acknowledge the efforts of all those who contributed to this document, through all its stages until this final version. Their efforts have resulted in a comprehensive, forward- looking strategy to keep Puerto Rico‘s forests as healthy natural resources and thriving into the future. Thanks go to the extensive efforts of the hard working staff of the Forest Service Bureau of the Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources (DNER), and the International Institute of Tropical Forestry (IITF), whose joint work have made this PRFASFR possible. Within the DNER, we also want to thank the Comprehensive Planning Area, in particular to its Acting Assistant Secretary Mr. José E. Basora Fagundo for devoting resources under his supervision exclusively for this task. Within ITTF, we want to highlight the immeasurable contribution of the restless editor Ms. Constance Carpenter, who always pushed us to strive for excellence. In addition, we want to thank the Southern Group of State Foresters for their grant supporting many of the maps enclosed and text in the initial stages of this document. We are also grateful to Geographic Consulting LLC, whose collaboration was made possible by sponsorship of IITF, for their wonderful editing work in the previous stages of the document. Thanks also go to particular DNER and IITF staff, to members of the State Technical Committee through its Forest and Wildlife Subcommittee, and to other external professionals, for their particular contributions to and their efforts bringing the PRSASFR together: Editing Contributors: Nicole Balloffet (USFS) Cristina Cabrera (DNER) Constance Carpenter (IITF) Geographic Consulting LLC Magaly Figueroa (IITF) Norma Lozada (DNER) José A. -

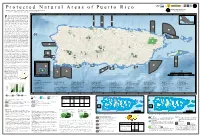

Protected Areas by Management 9

Unted States p Forest Department a Service DRNA of Agriculture g P r o t e c t e d N a t u r a l A r e a s o f P u e r to R i c o K E E P I N G C O M M ON S P E C I E S C O M M O N PRGAP ANALYSIS PROJECT William A. Gould, Maya Quiñones, Mariano Solórzano, Waldemar Alcobas, and Caryl Alarcón IITF GIS and Remote Sensing Lab A center for tropical landscape analysis U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, International Institute of Tropical Forestry . o c 67°30'0"W 67°20'0"W 67°10'0"W 67°0'0"W 66°50'0"W 66°40'0"W 66°30'0"W 66°20'0"W 66°10'0"W 66°0'0"W 65°50'0"W 65°40'0"W 65°30'0"W 65°20'0"W i R o t rotection of natural areas is essential to conserving biodiversity and r e u P maintaining ecosystem services. Benefits and services provided by natural United , Protected areas by management 9 States 1 areas are complex, interwoven, life-sustaining, and necessary for a healthy A t l a n t i c O c e a n 1 1 - 6 environment and a sustainable future (Daily et al. 1997). They include 2 9 0 clean water and air, sustainable wildlife populations and habitats, stable slopes, The Bahamas 0 P ccccccc R P productive soils, genetic reservoirs, recreational opportunities, and spiritual refugia. -

Puerto Rico Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy 2005

Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy Puerto Rico PUERTO RICO COMPREHENSIVE WILDLIFE CONSERVATION STRATEGY 2005 Miguel A. García José A. Cruz-Burgos Eduardo Ventosa-Febles Ricardo López-Ortiz ii Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy Puerto Rico ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Financial support for the completion of this initiative was provided to the Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources (DNER) by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) Federal Assistance Office. Special thanks to Mr. Michael L. Piccirilli, Ms. Nicole Jiménez-Cooper, Ms. Emily Jo Williams, and Ms. Christine Willis from the USFWS, Region 4, for their support through the preparation of this document. Thanks to the colleagues that participated in the Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy (CWCS) Steering Committee: Mr. Ramón F. Martínez, Mr. José Berríos, Mrs. Aida Rosario, Mr. José Chabert, and Dr. Craig Lilyestrom for their collaboration in different aspects of this strategy. Other colleagues from DNER also contributed significantly to complete this document within the limited time schedule: Ms. María Camacho, Mr. Ramón L. Rivera, Ms. Griselle Rodríguez Ferrer, Mr. Alberto Puente, Mr. José Sustache, Ms. María M. Santiago, Mrs. María de Lourdes Olmeda, Mr. Gustavo Olivieri, Mrs. Vanessa Gautier, Ms. Hana Y. López-Torres, Mrs. Carmen Cardona, and Mr. Iván Llerandi-Román. Also, special thanks to Mr. Juan Luis Martínez from the University of Puerto Rico, for designing the cover of this document. A number of collaborators participated in earlier revisions of this CWCS: Mr. Fernando Nuñez-García, Mr. José Berríos, Dr. Craig Lilyestrom, Mr. Miguel Figuerola and Mr. Leopoldo Miranda. A special recognition goes to the authors and collaborators of the supporting documents, particularly, Regulation No. -

Cook's Holly (Ilex Cookii)

Cook’s Holly (Ilex cookii) Image of the type specimen from the Herbarium of the New York Botanical Garden 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Caribbean Ecological Services Field Office Boquerón, Puerto Rico 5-YEAR REVIEW Cook’s Holly / Ilex cookii I. GENERAL INFORMATION A. Methodology used to complete the review: On April 9, 2010, the Service published a notice in the Federal Register announcing the 5-year review of Cook’s holly (Ilex cookii) and requested new information concerning the biology and status of the species (75 FR 18232). A 60-day comment period was opened. No comment letters were received from the public during this period. This 5-year review was finalized by a Service biologist and summarizes the information that the Service has gathered in the Cook’s holly file since the plant was listed on June 16, 1987. The sources of information used for this review included the original listing rule for the species, the recovery plan for Cook’s holly, and information provided by the University of Puerto Rico, Mayagüez Campus (UPRM). Under cooperative agreement with the Service, professors from UPRM, Dr. Duane A. Kolterman and Dr. Jesús D. Chinea, provided to the Service a draft 5-year review compiling all available information on Cook’s holly. They conducted literature research on the species, consulted with other specialists, and examined herbarium data from the University of Puerto Rico at Mayaguez (MAPR), Río Piedras Botanical Garden (UPR), University of Puerto Rico at Río Piedras (UPRRP), Department of Natural and Environmental Resources of Puerto Rico (SJ), New York Botanical Garden (NY), US National Herbarium (US), and University of Illinois (ILL). -

Villanueva-Rivera, L. J. 2006

CALLING ACTIVITY OF ELEUTHERODACTYLUS FROGS OF PUERTO RICO AND HABITAT DISTRIBUTION OF E. RICHMONDI by Luis J. Villanueva Rivera A thesis submitted to the Department of Biology COLLEGE OF NATURAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF PUERTO RICO RIO PIEDRAS CAMPUS In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN BIOLOGY MAY 2006 SAN JUAN, PUERTO RICO © 2006 Luis J. Villanueva Rivera A mi familia iii Acknowledgements I thank my family for their support and encouragement during these years. I also want to thank my thesis committee, J. Thomlinson, T. M. Aide, A. Sabat, and R. Thomas, for their help and suggestions. For sharing data I am grateful to A. Puente, N. Ríos, J. Delgado, and V. Cuevas. For insightful discussions I thank N. Ríos, M. Acevedo, J. Thomlinson, and T. M. Aide. For suggestions that resulted in the first chapter in its current form, I thank C. Restrepo, C. Monmany, and H. Perotto. This research was conducted under the authorization of the Department of Natural and Environmental Resources of Puerto Rico (permit #02-IC-068) and the United States Forest Service (permit #CNF-2038). Part of this research was funded thanks to a fellowship from the “Attaining Research Extensive University Status in Puerto Rico: Building a Competitive Infrastructure” award from the National Science Foundation (#0223152) to the Experimental Program to Stimulate Competitive Research at the University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras Campus. I also thank the Department of Biology, the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Research, and the CREST- Center for Applied Tropical Ecology and Conservation of the University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras Campus, for their support by providing several research and teaching assistantships. -

The Technological Embodiment of Colonialism in Puerto Rico

Anthurium: A Caribbean Studies Journal Volume 12 | Issue 2 Article 6 December 2015 The echnologT ical Embodiment of Colonialism in Puerto Rico Manuel G. Aviles-Santiago Arizona State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlyrepository.miami.edu/anthurium Recommended Citation Aviles-Santiago, Manuel G. (2015) "The eT chnological Embodiment of Colonialism in Puerto Rico," Anthurium: A Caribbean Studies Journal: Vol. 12 : Iss. 2 , Article 6. Available at: http://scholarlyrepository.miami.edu/anthurium/vol12/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthurium: A Caribbean Studies Journal by an authorized editor of Scholarly Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Aviles-Santiago: The Technological Embodiment of Colonialism in Puerto Rico Although the literature on colonial countries has long emphasized under- development as an effect of the ways in which the colonizing powers assert their monopolistic access to cutting-edge technology at the expense of the colonized (delayed technology transfer, for instance, or unilateral decision making on the part of the colonial government concerning implementation), this literature has not examined the connection between technology and colonialism in Puerto Rico. Puerto Rico provides a unique example of a colony under a supposedly pre- modern regime (Spain), as well as a hyper-modern and post-industrial one (the United States). Not that the technological space has been totally neglected in literature. There are, for instance, a few studies concerning particular technologies, including that of birth control, with a particular emphasis on sterilization, used during the 1920s-30s and that of media, in particular the advent of radio, film, and print media in the late 1940s.1 There is, however, no general historical account of the introduction, presence, and development of technology on the island. -

The Bees of Greater Puerto Rico (Hymenoptera: Apoidea: Anthophila)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Insecta Mundi Florida August 2008 The bees of Greater Puerto Rico (Hymenoptera: Apoidea: Anthophila) Julio A. Genaro York University, Toronto, [email protected] Nico M. Franz University of Puerto Rico, Mayagüez, PR, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi Part of the Entomology Commons Genaro, Julio A. and Franz, Nico M., "The bees of Greater Puerto Rico (Hymenoptera: Apoidea: Anthophila)" (2008). Insecta Mundi. 569. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi/569 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Florida at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Insecta Mundi by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. INSECTA MUNDI A Journal of World Insect Systematics 0040 The bees of Greater Puerto Rico (Hymenoptera: Apoidea: Anthophila) Julio A. Genaro Department of Biology, York University 4700 Keele St., Toronto, ON, M3J 1P3, Canada Nico M. Franz Department of Biology, University of Puerto Rico PO Box 9012, Mayagüez, PR 00681, U.S.A. Date of Issue: August 22, 2008 CENTER FOR SYSTEMATIC ENTOMOLOGY, INC., Gainesville, FL Julio A. Genaro and Nico M. Franz The bees of Greater Puerto Rico (Hymenoptera: Apoidea: Anthophila) Insecta Mundi 0040: 1-24 Published in 2008 by Center for Systematic Entomology, Inc. P. O. Box 147100 Gainesville, FL 32614-7100 U. S. A. http://www.centerforsystematicentomology.org/ Insecta Mundi is a journal primarily devoted to insect systematics, but articles can be published on any non-marine arthropod taxon. -

Ecology of Rare and Abundant Raptors on an Oceanic Island the Sharp-Shinned Hawk and Red-Tailed Hawk in Puerto Rico

Mississippi State University Scholars Junction Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 1-1-2018 Ecology of Rare and Abundant Raptors on an Oceanic Island the Sharp-Shinned Hawk and Red-Tailed Hawk in Puerto Rico Julio C. Gallardo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/td Recommended Citation Gallardo, Julio C., "Ecology of Rare and Abundant Raptors on an Oceanic Island the Sharp-Shinned Hawk and Red-Tailed Hawk in Puerto Rico" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 1615. https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/td/1615 This Dissertation - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Scholars Junction. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholars Junction. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Template B v3.0 (beta): Created by J. Nail 06/2015 Ecology of rare and abundant raptors on an oceanic island: the Sharp-shinned Hawk and Red-tailed Hawk in Puerto Rico By TITLE PAGE Julio C. Gallardo A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Mississippi State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Doctor of Philosophy Requirements for the Degree of Doctor in Philosophy in Forest Resources in the Department of Wildlife, Fisheries and Aquaculture Mississippi State, Mississippi August 2018 Copyright by COPYRIGHT PAGE Julio C. Gallardo 2018 Ecology of rare and abundant raptors on an oceanic island: the Sharp-shinned Hawk and Red-tailed Hawk in Puerto Rico By APPROVAL PAGE Julio C. Gallardo Approved: ____________________________________ Francisco J. Vilella (Major Professor) ____________________________________ Jerrold L. Belant (Committee Member) ____________________________________ Bruce D. -

Specialist Internet Report

GOBIERNO DE PUERTO RICO DEPARTAMENTO DE HACIENDA ESPECIALISTAS EN PLANILLAS DECLARACIONES O RECLAMACIONES DE REINTEGRO AL 23 DE DICIEMBRE DE 2013 NOMBRE DEL ESPECIALISTA DIRECCION 1 DIRECCION 2 CIUDAD ESTADO C-POSTAL TELEFONO COHN REZNICK LLC PLAZA SCOTIABANK SUITE 700 273 PONCE DE ADJUNTAS PR 00917 (310)843-8216 LEON AVE. [email protected] SANTIAGO VEGA WILNELIA CARR 518 ADJUNTAS PR 00601 (787)487-5481 [email protected] ACEVEDO BONILLA YANIRA CARR 115 KM 11.6 INTERIOR BO PUEBLO ADJUNTAS PR 00677 (787)934-8276 [email protected] BARRETO CUADRADO ALEXANDER BARRIO RIO CAÑAS SECTOR CARR #1 KM 27.1 ADJUNTAS PR 00725 (787)286-3914 [email protected] COLON SANCHEZ IRIS Y. URB VISTA DE RIO BLANCO CALLE 1 #59 ADJUNTAS PR 00744 (787)514-5582 [email protected] ESCOBALES PACHECO ZULMA BO LA OLIMPIA B-1 ADJUNTAS PR 00601 (787)408-0997 [email protected] GARCIA RIVERA ANTONIO BO. VACAS SALTILLO CARR 388 KM. 0.1 ADJUNTAS PR 00601 (787)829-1059 [email protected] LUGO FIGUEROA ARIEL E 31 CALLE MUÑOZ RIVERA ADJUNTAS PR 00601 (787)614-8127 [email protected] LUGO VEGA LUIS D. 7 CALLE JOAQUIN ANDINO ADJUNTAS PR 00601 (787)317-7809 [email protected] MARIANI TORRES JOSE A TEODORO FIGUEROA #2 SUITE 3 CARR 135 ADJUNTAS PR 00601 (787)829-4910 [email protected] ORTIZ SANTIAGO VICKY #2 CALLE ALFREDO PALMIERI ADJUNTAS PR 00601 (787)232-6575 [email protected] PEREZ GONZALEZ ALEJANDRO LA OLIMPIA SECTOR BALLESTER ADJUNTAS PR 00601 (787)372-6860 FINAL [email protected] QUILES FELICIANO JORGE I CALLE JOAQUIN MARTINEZ DE ADJUNTAS PR 00601 (787)314-1147 ANDINO #C-4 1 GOBIERNO DE PUERTO RICO DEPARTAMENTO DE HACIENDA ESPECIALISTAS EN PLANILLAS DECLARACIONES O RECLAMACIONES DE REINTEGRO AL 23 DE DICIEMBRE DE 2013 NOMBRE DEL ESPECIALISTA DIRECCION 1 DIRECCION 2 CIUDAD ESTADO C-POSTAL TELEFONO RAMIREZ LATORRE RENE G. -

Puerto Rico Forest Action Plan

National Priorities Section Puerto Rico Forest Action Plan Submitted to: USDA is an equal opportunity provider, employer and lender. This publication was made possible through a grant from the USDA Forest Service CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................... 7 1. CONSERVING WORKING FOREST LANDSCAPES ................................................................................ 8 1. Continue land acquisition programs of key private forested land by available mechanisms ......... 8 2. Promote conservation easements on private forested land ........................................................... 10 3. Provide adequate conservation management for private forests through Forest Stewardship plans .................................................................................................................................................. 11 4. Develop forest and wildlife interpretation trainings ......................................................................... 12 5. Develop management information on agroforestry practices suitable for the Río Loco Watershed at Guánica Bay Watershed .............................................................................................................. 14 6. Increase capacity of community to manage trees ......................................................................... 16 7. Increase tree canopy cover and condition ....................................................................................