Puerto Rico FOREST ACTION PLAN, 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Declaración De Impacto Ambiental Estratégica

Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico Departamento de Recursos Naturales y Ambientales DECLARACIÓN DE IMPACTO AMBIENTAL ESTRATÉGICA ESTUDIO DEL CARSO Septiembre 2009 Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico Departamento de Recursos Naturales y Ambientales DECLARACIÓN DE IMPACTO AMBIENTAL ESTRATÉGICA ESTUDIO DEL CARSO Septiembre 2009 HOJA PREÁMBULO DIA- Núm: JCA-__-____(PR) Agencia: Departamento de Recursos Naturales y Ambientales Título de la acción propuesta: Adopción del Estudio del Carso Funcionario responsable: Daniel J. Galán Kercadó Secretario Departamento de Recursos Naturales y Ambientales PO Box 366147 San Juan, PR 00936-6147 787 999-2200 Acción: Declaración de Impacto Ambiental – Estratégica Estudio del Carso Resumen: La acción propuesta consiste en la adopción del Estudio del Carso. En este documento se presenta el marco legal que nos lleva a la preparación de este estudio científico y se describen las características geológicas, hidrológicas, ecológicas, paisajísticas, recreativas y culturales que permitieron la delimitación de un área que abarca unas 219,804 cuerdas y que permitirá conservar una adecuada representación de los elementos irremplazables presente en el complejo ecosistema conocido como carso. Asimismo, se evalúa su estrecha relación con las políticas públicas asociadas a los usos de los terrenos y como se implantarán los hallazgos mediante la enmienda de los reglamentos y planes aplicables. Fecha: Septiembre de 2009 i TABLA DE CONTENIDO Capítulo I000Descripción del Estudio del Carso .................................................1 -

The Initiative Towards Implementing Best Environmental Management

Encouraging Best Environmental Management Practices In the Hotels & Inns of Puerto Rico An Interactive Qualifying Project Report submitted to the faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science Sponsored by: Compañía de Tourismo de Puerto Rico Submitted by: Kathryn Bomba Nathan Griggs Ross Hudon Jennifer Thompson Project Advisors: Professor Dominic Golding Professor John Zeugner Project Liaisons: Angel La Fontaine-Madera Ana Leticia Vélez Santiago This project report is submitted in partial fulfillment of the degree requirements of Worcester Polytechnic Institute. The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions or opinions of Compañía de Tourismo de Puerto Rico or Worcester Polytechnic Institute. This report is the product of an education program, and is intended to serve as partial documentation for the evaluation of academic achievement. The report should not be construed as a working document by the reader. -May 1, 2008- Abstract This project, sponsored by the Compañía de Tourismo de Puerto Rico focused on expanding Best Environmental Practices in the small inns and hotels of Puerto Rico. The project included interviews with CTPR staff, outside experts, audit visits to eight inns, and extensive background research. The project concludes with several recommendations with appropriate initial suggestions to CTPR for BEMP expansion including: a webpage for small inns and hotels with extensive BEMP information, a brochure explaining BEMPs, and a student involvement program. ii Executive Summary The goal of this project is to address the issue of communication between the Compañía de Tourismo de Puerto Rico (CTPR) and small hotels and inns in Puerto Rico regarding the use of best environmental management practices (BEMPs). -

Reporton the Rare Plants of Puerto Rico

REPORTON THE RARE PLANTS OF PUERTO RICO tii:>. CENTER FOR PLANT CONSERVATION ~ Missouri Botanical Garden St. Louis, Missouri July 15, l' 992 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Center for Plant Conservation would like to acknowledge the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and the W. Alton Jones Foundation for their generous support of the Center's work in the priority region of Puerto Rico. We would also like to thank all the participants in the task force meetings, without whose information this report would not be possible. Cover: Zanthoxy7um thomasianum is known from several sites in Puerto Rico and the U.S . Virgin Islands. It is a small shrub (2-3 meters) that grows on the banks of cliffs. Threats to this taxon include development, seed consumption by insects, and road erosion. The seeds are difficult to germinate, but Fairchild Tropical Garden in Miami has plants growing as part of the Center for Plant Conservation's .National Collection of Endangered Plants. (Drawing taken from USFWS 1987 Draft Recovery Plan.) REPORT ON THE RARE PLANTS OF PUERTO RICO TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements A. Summary 8. All Puerto Rico\Virgin Islands Species of Conservation Concern Explanation of Attached Lists C. Puerto Rico\Virgin Islands [A] and [8] species D. Blank Taxon Questionnaire E. Data Sources for Puerto Rico\Virgin Islands [A] and [B] species F. Pue~to Rico\Virgin Islands Task Force Invitees G. Reviewers of Puerto Rico\Virgin Islands [A] and [8] Species REPORT ON THE RARE PLANTS OF PUERTO RICO SUMMARY The Center for Plant Conservation (Center) has held two meetings of the Puerto Rlco\Virgin Islands Task Force in Puerto Rico. -

Monocotyledons and Gymnosperms of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Contributions from the United States National Herbarium Volume 52: 1-415 Monocotyledons and Gymnosperms of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands Editors Pedro Acevedo-Rodríguez and Mark T. Strong Department of Botany National Museum of Natural History Washington, DC 2005 ABSTRACT Acevedo-Rodríguez, Pedro and Mark T. Strong. Monocots and Gymnosperms of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. Contributions from the United States National Herbarium, volume 52: 415 pages (including 65 figures). The present treatment constitutes an updated revision for the monocotyledon and gymnosperm flora (excluding Orchidaceae and Poaceae) for the biogeographical region of Puerto Rico (including all islets and islands) and the Virgin Islands. With this contribution, we fill the last major gap in the flora of this region, since the dicotyledons have been previously revised. This volume recognizes 33 families, 118 genera, and 349 species of Monocots (excluding the Orchidaceae and Poaceae) and three families, three genera, and six species of gymnosperms. The Poaceae with an estimated 89 genera and 265 species, will be published in a separate volume at a later date. When Ackerman’s (1995) treatment of orchids (65 genera and 145 species) and the Poaceae are added to our account of monocots, the new total rises to 35 families, 272 genera and 759 species. The differences in number from Britton’s and Wilson’s (1926) treatment is attributed to changes in families, generic and species concepts, recent introductions, naturalization of introduced species and cultivars, exclusion of cultivated plants, misdeterminations, and discoveries of new taxa or new distributional records during the last seven decades. -

Puerto Rico: Nature and Birding January 3-11, 2013

PO Box 16545 Portal, AZ 85632 Phone 520.558.1146 Toll free 866.900.1146 Fax 650.471.7667 Email [email protected] Puerto Rico: Nature and Birding January 3-11, 2013 “Peg Abbott is a pro...full of knowledge and diplomacy. She is generous with her time and attention to our questions.” - Rolla Wagner Join us this January to explore, among varied island habitats, the only tropical forest in America’s National Forest system – in Puerto Rico! The 28,000 acre-El Yunque National Forest is located in the rugged Sierra de Luquillo Mountains, just 25 miles east-southeast of San Juan. In addition to this lush, exciting gem of the US National Forest system, we visit Laguna Cartagena National Wildlife Refuge and several state forest and private reserves. Puerto Rico has over 260 species of birds, more than a dozen of which occur nowhere else. With an excellent road system and an accomplished local guide, we have a great chance to see a good portion of the island’s 17* endemics, and a good number of the twenty-or-so additional Caribbean regional specialties. We visit several Important Bird Areas designated by Birdlife International. There is a good field guide for the island, written by Herbert Raffaele, the Birds of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. A nice addition is the newer, Puerto Rico´s Birds in Photograph by Mark Oberle, which includes a CD with the bird sounds. We’ll also focus on the island’s lush (east side) and arid (southwest corner, due to a mountain rain shadow effect) flora. -

Evaluación De Los Recursos Forestales De Puerto Rico

Department of Natural and Environmental Resources GOVERNMENT OF PUERTO RICO Puerto Rico Statewide Assessment and Strategies for Forest Resources Acknowledgements Many people have contributed to this final edition of the Puerto Rico Statewide Assessment and Strategies for Forest Resources (PRSASFR) in a variety of ways. We gratefully acknowledge the efforts of all those who contributed to this document, through all its stages until this final version. Their efforts have resulted in a comprehensive, forward- looking strategy to keep Puerto Rico‘s forests as healthy natural resources and thriving into the future. Thanks go to the extensive efforts of the hard working staff of the Forest Service Bureau of the Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources (DNER), and the International Institute of Tropical Forestry (IITF), whose joint work have made this PRFASFR possible. Within the DNER, we also want to thank the Comprehensive Planning Area, in particular to its Acting Assistant Secretary Mr. José E. Basora Fagundo for devoting resources under his supervision exclusively for this task. Within ITTF, we want to highlight the immeasurable contribution of the restless editor Ms. Constance Carpenter, who always pushed us to strive for excellence. In addition, we want to thank the Southern Group of State Foresters for their grant supporting many of the maps enclosed and text in the initial stages of this document. We are also grateful to Geographic Consulting LLC, whose collaboration was made possible by sponsorship of IITF, for their wonderful editing work in the previous stages of the document. Thanks also go to particular DNER and IITF staff, to members of the State Technical Committee through its Forest and Wildlife Subcommittee, and to other external professionals, for their particular contributions to and their efforts bringing the PRSASFR together: Editing Contributors: Nicole Balloffet (USFS) Cristina Cabrera (DNER) Constance Carpenter (IITF) Geographic Consulting LLC Magaly Figueroa (IITF) Norma Lozada (DNER) José A. -

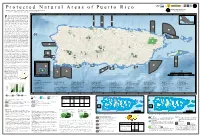

Protected Areas by Management 9

Unted States p Forest Department a Service DRNA of Agriculture g P r o t e c t e d N a t u r a l A r e a s o f P u e r to R i c o K E E P I N G C O M M ON S P E C I E S C O M M O N PRGAP ANALYSIS PROJECT William A. Gould, Maya Quiñones, Mariano Solórzano, Waldemar Alcobas, and Caryl Alarcón IITF GIS and Remote Sensing Lab A center for tropical landscape analysis U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, International Institute of Tropical Forestry . o c 67°30'0"W 67°20'0"W 67°10'0"W 67°0'0"W 66°50'0"W 66°40'0"W 66°30'0"W 66°20'0"W 66°10'0"W 66°0'0"W 65°50'0"W 65°40'0"W 65°30'0"W 65°20'0"W i R o t rotection of natural areas is essential to conserving biodiversity and r e u P maintaining ecosystem services. Benefits and services provided by natural United , Protected areas by management 9 States 1 areas are complex, interwoven, life-sustaining, and necessary for a healthy A t l a n t i c O c e a n 1 1 - 6 environment and a sustainable future (Daily et al. 1997). They include 2 9 0 clean water and air, sustainable wildlife populations and habitats, stable slopes, The Bahamas 0 P ccccccc R P productive soils, genetic reservoirs, recreational opportunities, and spiritual refugia. -

Exempted Trees List

Prohibited Plants List The following plants should not be planted within the City of North Miami. They do not require a Tree Removal Permit to remove. City of North Miami, 2017 Comprehensive List of Exempted Species Pg. 1/4 Scientific Name Common Name Abrus precatorius Rosary pea Acacia auriculiformis Earleaf acacia Adenanthera pavonina Red beadtree, red sandalwood Aibezzia lebbek woman's tongue Albizia lebbeck Woman's tongue, lebbeck tree, siris tree Antigonon leptopus Coral vine, queen's jewels Araucaria heterophylla Norfolk Island pine Ardisia crenata Scratchthroat, coral ardisia Ardisia elliptica Shoebutton, shoebutton ardisia Bauhinia purpurea orchid tree; Butterfly Tree; Mountain Ebony Bauhinia variegate orchid tree; Mountain Ebony; Buddhist Bauhinia Bischofia javanica bishop wood Brassia actino-phylla schefflera Calophyllum antillanum =C inophyllum Casuarina equisetifolia Australian pine Casuarina spp. Australian pine, sheoak, beefwood Catharanthus roseus Madagascar periwinkle, Rose Periwinkle; Old Maid; Cape Periwinkle Cestrum diurnum Dayflowering jessamine, day blooming jasmine, day jessamine Cinnamomum camphora Camphortree, camphor tree Colubrina asiatica Asian nakedwood, leatherleaf, latherleaf Cupaniopsis anacardioides Carrotwood Dalbergia sissoo Indian rosewood, sissoo Dioscorea alata White yam, winged yam Pg. 2/4 Comprehensive List of Exempted Species Scientific Name Common Name Dioscorea bulbifera Air potato, bitter yam, potato vine Eichhornia crassipes Common water-hyacinth, water-hyacinth Epipremnum pinnatum pothos; Taro -

Puerto Rico Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy 2005

Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy Puerto Rico PUERTO RICO COMPREHENSIVE WILDLIFE CONSERVATION STRATEGY 2005 Miguel A. García José A. Cruz-Burgos Eduardo Ventosa-Febles Ricardo López-Ortiz ii Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy Puerto Rico ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Financial support for the completion of this initiative was provided to the Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources (DNER) by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) Federal Assistance Office. Special thanks to Mr. Michael L. Piccirilli, Ms. Nicole Jiménez-Cooper, Ms. Emily Jo Williams, and Ms. Christine Willis from the USFWS, Region 4, for their support through the preparation of this document. Thanks to the colleagues that participated in the Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy (CWCS) Steering Committee: Mr. Ramón F. Martínez, Mr. José Berríos, Mrs. Aida Rosario, Mr. José Chabert, and Dr. Craig Lilyestrom for their collaboration in different aspects of this strategy. Other colleagues from DNER also contributed significantly to complete this document within the limited time schedule: Ms. María Camacho, Mr. Ramón L. Rivera, Ms. Griselle Rodríguez Ferrer, Mr. Alberto Puente, Mr. José Sustache, Ms. María M. Santiago, Mrs. María de Lourdes Olmeda, Mr. Gustavo Olivieri, Mrs. Vanessa Gautier, Ms. Hana Y. López-Torres, Mrs. Carmen Cardona, and Mr. Iván Llerandi-Román. Also, special thanks to Mr. Juan Luis Martínez from the University of Puerto Rico, for designing the cover of this document. A number of collaborators participated in earlier revisions of this CWCS: Mr. Fernando Nuñez-García, Mr. José Berríos, Dr. Craig Lilyestrom, Mr. Miguel Figuerola and Mr. Leopoldo Miranda. A special recognition goes to the authors and collaborators of the supporting documents, particularly, Regulation No. -

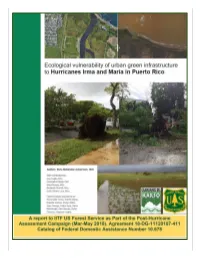

U.S. Forest Service Report

TABLE OF CONTENTS I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY……………………………………………………………….…...….1 II. CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION A. Background..………………………………………………………………………….....4 B. Purpose…..………..…………………………………………………….......................4 III. CHAPTER 2. METHODS A. Changes in Ecosystem Services in Three Municipalities (i-Tree Canopy)............6 B. Fine-scale evaluation of ecosystem services changes in Santurce (i-Tree Eco)...9 C. Fine-scale evaluation of ecosystem services changes in San Juan residential yards (i-Tree Eco)................................................................................................10 D. List and definitions of ecosystem services exported…...…….…...………..……..11 IV. CHAPTER 3. RESULTS A. Percent tree cover area / ecosystem services in three municipalities (i-Tree Canopy)...........................................................................................................….13 B. Changes in ecosystem services at the municipal scale. (i-Tree Canopy)............16 C. Changes in vegetation and ecosystem services in areas with multiple land uses in the Santurce Peninsula (i-Tree Eco)……………………………...……..............17 D. Changes in vegetation and ecosystem services in residential yards of the Río Piedras Watershed (i-Tree Eco)..........................................................................19 V. CHAPTER 4. DISCUSSION A. Meaning of inventory results………………...…………………………………….....21 B. Recommendations………………..…………………….……………………………..24 VI. REFERENCES...…………………..……….………………………………………..………...25 VII. APPENDICES A. App 1. Site Coordinates -

Sustainability Bond Framework

Sustainability Bond Framework April 2021 Part 1: Introduction FedEx Corporation (“FedEx”, “the Company”, • FedEx Freight: FedEx Freight Corporation (“FedEx “our”, “we” or “us”) is the parent holding company Freight”) is a leading North American provider of providing strategic direction to the FedEx portfolio less-than-truckload (“LTL”) freight services across of companies. FedEx provides a broad portfolio all lengths of haul, offering: FedEx Freight Priority, of transportation, e-commerce, and business when speed is critical to meet a customer’s supply services through companies competing collectively, chain needs; FedEx Freight Economy, when a operating collaboratively, and innovating digitally customer can trade time for cost savings; and under the respected FedEx brand. FedEx Freight Direct, a service to meet the needs of the growing e-commerce market for delivery These companies are included in the following of heavy, bulky products to or through the door reportable business segments: for residences and businesses. FedEx Freight also offers freight delivery service to most points in • FedEx Express: Federal Express Corporation Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. (“FedEx Express”) is the world’s largest express transportation company, offering time-definite • FedEx Services: FedEx Corporate Services, Inc. delivery to more than 220 countries and (“FedEx Services”) provides sales, marketing, territories, connecting markets that comprise information technology, communications, more than 99% of the world’s gross domestic customer service, technical support, billing product. and collection services, and certain back-office functions that support our transportation • FedEx Ground: FedEx Ground Package System, segments. Inc. (“FedEx Ground”) is a leading North American provider of small-package ground delivery • FedEx Logistics: FedEx Logistics Inc. -

Inventario De Las Plantas Cubanas Silvestres Parientes De Las Cultivadas De Importancia Alimenticia, Agronómica Y Forestal

Inventario de las plantas cubanas silvestres parientes de las cultivadas de importancia alimenticia, agronómica y forestal por Werner Greuter y Rosa Rankin Rodríguez A Checklist of Cuban wild relatives of cultivated plants important for food, agriculture and forestry by Werner Greuter and Rosa Rankin Rodríguez Botanischer Garten und Botanisches Museum Berlin Jardín Botánico Nacional, Universidad de La Habana Publicado en el Internet el 22 marzo 2019 Published online on 22 March 2019 ISBN 978-3-946292-33-3 DOI: https://doi.org/10.3372/cubalist.2019.1 Published by: Botanischer Garten und Botanisches Museum Berlin Zentraleinrichtung der Freien Universität Berlin Königin-Luise-Str. 6–8, D-14195 Berlin, Germany © 2019 The Authors. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence (CC BY 4.0), which permits unrestricted use provided the original author and source are credited (see https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) Greuter & Rankin – Parientes Cubanos Silvestres de Plantas Cultivadas 3 Inventario de las plantas cubanas silvestres parientes de las cultivadas de importancia alimenticia, agronómica y forestal Werner Greuter & Rosa Rankin Rodríguez Introducción Este Inventario se generó para servir de base a los trabajos de la reunión anual del Grupo de Especialistas en Plantas Cubanas de la Comisión para la supervivencia de las especies de la UICN en La Habana, Cuba, del 13 al 15 de Marzo del 2019. Abarca 57 familias y 859 taxones de plantas vasculares de la flora espontánea cubana congenéricas con las plantas útiles de importancia al nivel global y que puedan servir para enriquecer su patrimonio genético en el desarrollo de nuevas variedades con mejores propiedades de productividad y/o resistencia y cuya conservación por ende es de importancia prioritaria para la sobrevivencia de la raza humana (ver Meta 13 de las Metas nacionales cubanas para la diversidad biológica 2016-2020).