Cook's Holly (Ilex Cookii)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reporton the Rare Plants of Puerto Rico

REPORTON THE RARE PLANTS OF PUERTO RICO tii:>. CENTER FOR PLANT CONSERVATION ~ Missouri Botanical Garden St. Louis, Missouri July 15, l' 992 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Center for Plant Conservation would like to acknowledge the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and the W. Alton Jones Foundation for their generous support of the Center's work in the priority region of Puerto Rico. We would also like to thank all the participants in the task force meetings, without whose information this report would not be possible. Cover: Zanthoxy7um thomasianum is known from several sites in Puerto Rico and the U.S . Virgin Islands. It is a small shrub (2-3 meters) that grows on the banks of cliffs. Threats to this taxon include development, seed consumption by insects, and road erosion. The seeds are difficult to germinate, but Fairchild Tropical Garden in Miami has plants growing as part of the Center for Plant Conservation's .National Collection of Endangered Plants. (Drawing taken from USFWS 1987 Draft Recovery Plan.) REPORT ON THE RARE PLANTS OF PUERTO RICO TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements A. Summary 8. All Puerto Rico\Virgin Islands Species of Conservation Concern Explanation of Attached Lists C. Puerto Rico\Virgin Islands [A] and [8] species D. Blank Taxon Questionnaire E. Data Sources for Puerto Rico\Virgin Islands [A] and [B] species F. Pue~to Rico\Virgin Islands Task Force Invitees G. Reviewers of Puerto Rico\Virgin Islands [A] and [8] Species REPORT ON THE RARE PLANTS OF PUERTO RICO SUMMARY The Center for Plant Conservation (Center) has held two meetings of the Puerto Rlco\Virgin Islands Task Force in Puerto Rico. -

Monocotyledons and Gymnosperms of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Contributions from the United States National Herbarium Volume 52: 1-415 Monocotyledons and Gymnosperms of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands Editors Pedro Acevedo-Rodríguez and Mark T. Strong Department of Botany National Museum of Natural History Washington, DC 2005 ABSTRACT Acevedo-Rodríguez, Pedro and Mark T. Strong. Monocots and Gymnosperms of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. Contributions from the United States National Herbarium, volume 52: 415 pages (including 65 figures). The present treatment constitutes an updated revision for the monocotyledon and gymnosperm flora (excluding Orchidaceae and Poaceae) for the biogeographical region of Puerto Rico (including all islets and islands) and the Virgin Islands. With this contribution, we fill the last major gap in the flora of this region, since the dicotyledons have been previously revised. This volume recognizes 33 families, 118 genera, and 349 species of Monocots (excluding the Orchidaceae and Poaceae) and three families, three genera, and six species of gymnosperms. The Poaceae with an estimated 89 genera and 265 species, will be published in a separate volume at a later date. When Ackerman’s (1995) treatment of orchids (65 genera and 145 species) and the Poaceae are added to our account of monocots, the new total rises to 35 families, 272 genera and 759 species. The differences in number from Britton’s and Wilson’s (1926) treatment is attributed to changes in families, generic and species concepts, recent introductions, naturalization of introduced species and cultivars, exclusion of cultivated plants, misdeterminations, and discoveries of new taxa or new distributional records during the last seven decades. -

Evaluación De Los Recursos Forestales De Puerto Rico

Department of Natural and Environmental Resources GOVERNMENT OF PUERTO RICO Puerto Rico Statewide Assessment and Strategies for Forest Resources Acknowledgements Many people have contributed to this final edition of the Puerto Rico Statewide Assessment and Strategies for Forest Resources (PRSASFR) in a variety of ways. We gratefully acknowledge the efforts of all those who contributed to this document, through all its stages until this final version. Their efforts have resulted in a comprehensive, forward- looking strategy to keep Puerto Rico‘s forests as healthy natural resources and thriving into the future. Thanks go to the extensive efforts of the hard working staff of the Forest Service Bureau of the Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources (DNER), and the International Institute of Tropical Forestry (IITF), whose joint work have made this PRFASFR possible. Within the DNER, we also want to thank the Comprehensive Planning Area, in particular to its Acting Assistant Secretary Mr. José E. Basora Fagundo for devoting resources under his supervision exclusively for this task. Within ITTF, we want to highlight the immeasurable contribution of the restless editor Ms. Constance Carpenter, who always pushed us to strive for excellence. In addition, we want to thank the Southern Group of State Foresters for their grant supporting many of the maps enclosed and text in the initial stages of this document. We are also grateful to Geographic Consulting LLC, whose collaboration was made possible by sponsorship of IITF, for their wonderful editing work in the previous stages of the document. Thanks also go to particular DNER and IITF staff, to members of the State Technical Committee through its Forest and Wildlife Subcommittee, and to other external professionals, for their particular contributions to and their efforts bringing the PRSASFR together: Editing Contributors: Nicole Balloffet (USFS) Cristina Cabrera (DNER) Constance Carpenter (IITF) Geographic Consulting LLC Magaly Figueroa (IITF) Norma Lozada (DNER) José A. -

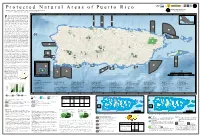

Protected Areas by Management 9

Unted States p Forest Department a Service DRNA of Agriculture g P r o t e c t e d N a t u r a l A r e a s o f P u e r to R i c o K E E P I N G C O M M ON S P E C I E S C O M M O N PRGAP ANALYSIS PROJECT William A. Gould, Maya Quiñones, Mariano Solórzano, Waldemar Alcobas, and Caryl Alarcón IITF GIS and Remote Sensing Lab A center for tropical landscape analysis U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, International Institute of Tropical Forestry . o c 67°30'0"W 67°20'0"W 67°10'0"W 67°0'0"W 66°50'0"W 66°40'0"W 66°30'0"W 66°20'0"W 66°10'0"W 66°0'0"W 65°50'0"W 65°40'0"W 65°30'0"W 65°20'0"W i R o t rotection of natural areas is essential to conserving biodiversity and r e u P maintaining ecosystem services. Benefits and services provided by natural United , Protected areas by management 9 States 1 areas are complex, interwoven, life-sustaining, and necessary for a healthy A t l a n t i c O c e a n 1 1 - 6 environment and a sustainable future (Daily et al. 1997). They include 2 9 0 clean water and air, sustainable wildlife populations and habitats, stable slopes, The Bahamas 0 P ccccccc R P productive soils, genetic reservoirs, recreational opportunities, and spiritual refugia. -

Puerto Rico Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy 2005

Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy Puerto Rico PUERTO RICO COMPREHENSIVE WILDLIFE CONSERVATION STRATEGY 2005 Miguel A. García José A. Cruz-Burgos Eduardo Ventosa-Febles Ricardo López-Ortiz ii Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy Puerto Rico ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Financial support for the completion of this initiative was provided to the Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources (DNER) by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) Federal Assistance Office. Special thanks to Mr. Michael L. Piccirilli, Ms. Nicole Jiménez-Cooper, Ms. Emily Jo Williams, and Ms. Christine Willis from the USFWS, Region 4, for their support through the preparation of this document. Thanks to the colleagues that participated in the Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy (CWCS) Steering Committee: Mr. Ramón F. Martínez, Mr. José Berríos, Mrs. Aida Rosario, Mr. José Chabert, and Dr. Craig Lilyestrom for their collaboration in different aspects of this strategy. Other colleagues from DNER also contributed significantly to complete this document within the limited time schedule: Ms. María Camacho, Mr. Ramón L. Rivera, Ms. Griselle Rodríguez Ferrer, Mr. Alberto Puente, Mr. José Sustache, Ms. María M. Santiago, Mrs. María de Lourdes Olmeda, Mr. Gustavo Olivieri, Mrs. Vanessa Gautier, Ms. Hana Y. López-Torres, Mrs. Carmen Cardona, and Mr. Iván Llerandi-Román. Also, special thanks to Mr. Juan Luis Martínez from the University of Puerto Rico, for designing the cover of this document. A number of collaborators participated in earlier revisions of this CWCS: Mr. Fernando Nuñez-García, Mr. José Berríos, Dr. Craig Lilyestrom, Mr. Miguel Figuerola and Mr. Leopoldo Miranda. A special recognition goes to the authors and collaborators of the supporting documents, particularly, Regulation No. -

Guide to Theecological Systemsof Puerto Rico

United States Department of Agriculture Guide to the Forest Service Ecological Systems International Institute of Tropical Forestry of Puerto Rico General Technical Report IITF-GTR-35 June 2009 Gary L. Miller and Ariel E. Lugo The Forest Service of the U.S. Department of Agriculture is dedicated to the principle of multiple use management of the Nation’s forest resources for sustained yields of wood, water, forage, wildlife, and recreation. Through forestry research, cooperation with the States and private forest owners, and management of the National Forests and national grasslands, it strives—as directed by Congress—to provide increasingly greater service to a growing Nation. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD).To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W. Washington, DC 20250-9410 or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Authors Gary L. Miller is a professor, University of North Carolina, Environmental Studies, One University Heights, Asheville, NC 28804-3299. -

Declining Human Population but Increasing Residential Development Around Protected Areas in Puerto Rico

Biological Conservation 209 (2017) 473–481 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Biological Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/bioc Declining human population but increasing residential development around protected areas in Puerto Rico J. Castro-Prieto a,c,⁎, S. Martinuzzi b, V.C. Radeloff b,D.P.Helmersb,M.Quiñonesc,W.A.Gouldc a Department of Environmental Sciences, College of Natural Sciences, University of Puerto Rico, PO Box 23341, San Juan 00931-3341, Puerto Rico b SILVIS Lab, Department of Forest and Wildlife Ecology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1630 Linden Drive, Madison, WI 53706, USA c International Institute of Tropical Forestry, USDA Forest Service, 1201 Ceiba Street, Rio Piedras, 00926, Puerto Rico article info abstract Article history: Increasing residential development around protected areas is a major threat for protected areas worldwide, and Received 21 September 2016 human population growth is often the most important cause. However, population is decreasing in many regions Received in revised form 19 January 2017 as a result of socio-economic changes, and it is unclear how residential development around protected areas is Accepted 19 February 2017 affected in these situations. We investigated whether decreasing human population alleviates pressures from Available online xxxx residential development around protected areas, using Puerto Rico—an island with declining population—as a case study. We calculated population and housing changes from the 2000 to 2010 census around 124 protected Keywords: Human-population areas, using buffers of different sizes. We found that the number of houses around protected areas continued to Island increase while population declined both around protected areas and island-wide. -

Villanueva-Rivera, L. J. 2006

CALLING ACTIVITY OF ELEUTHERODACTYLUS FROGS OF PUERTO RICO AND HABITAT DISTRIBUTION OF E. RICHMONDI by Luis J. Villanueva Rivera A thesis submitted to the Department of Biology COLLEGE OF NATURAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF PUERTO RICO RIO PIEDRAS CAMPUS In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN BIOLOGY MAY 2006 SAN JUAN, PUERTO RICO © 2006 Luis J. Villanueva Rivera A mi familia iii Acknowledgements I thank my family for their support and encouragement during these years. I also want to thank my thesis committee, J. Thomlinson, T. M. Aide, A. Sabat, and R. Thomas, for their help and suggestions. For sharing data I am grateful to A. Puente, N. Ríos, J. Delgado, and V. Cuevas. For insightful discussions I thank N. Ríos, M. Acevedo, J. Thomlinson, and T. M. Aide. For suggestions that resulted in the first chapter in its current form, I thank C. Restrepo, C. Monmany, and H. Perotto. This research was conducted under the authorization of the Department of Natural and Environmental Resources of Puerto Rico (permit #02-IC-068) and the United States Forest Service (permit #CNF-2038). Part of this research was funded thanks to a fellowship from the “Attaining Research Extensive University Status in Puerto Rico: Building a Competitive Infrastructure” award from the National Science Foundation (#0223152) to the Experimental Program to Stimulate Competitive Research at the University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras Campus. I also thank the Department of Biology, the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Research, and the CREST- Center for Applied Tropical Ecology and Conservation of the University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras Campus, for their support by providing several research and teaching assistantships. -

The Technological Embodiment of Colonialism in Puerto Rico

Anthurium: A Caribbean Studies Journal Volume 12 | Issue 2 Article 6 December 2015 The echnologT ical Embodiment of Colonialism in Puerto Rico Manuel G. Aviles-Santiago Arizona State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlyrepository.miami.edu/anthurium Recommended Citation Aviles-Santiago, Manuel G. (2015) "The eT chnological Embodiment of Colonialism in Puerto Rico," Anthurium: A Caribbean Studies Journal: Vol. 12 : Iss. 2 , Article 6. Available at: http://scholarlyrepository.miami.edu/anthurium/vol12/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthurium: A Caribbean Studies Journal by an authorized editor of Scholarly Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Aviles-Santiago: The Technological Embodiment of Colonialism in Puerto Rico Although the literature on colonial countries has long emphasized under- development as an effect of the ways in which the colonizing powers assert their monopolistic access to cutting-edge technology at the expense of the colonized (delayed technology transfer, for instance, or unilateral decision making on the part of the colonial government concerning implementation), this literature has not examined the connection between technology and colonialism in Puerto Rico. Puerto Rico provides a unique example of a colony under a supposedly pre- modern regime (Spain), as well as a hyper-modern and post-industrial one (the United States). Not that the technological space has been totally neglected in literature. There are, for instance, a few studies concerning particular technologies, including that of birth control, with a particular emphasis on sterilization, used during the 1920s-30s and that of media, in particular the advent of radio, film, and print media in the late 1940s.1 There is, however, no general historical account of the introduction, presence, and development of technology on the island. -

Logbook Endorsement. He May Not Controlled Airspace: All Aircraft

2 2 9 2 8 Federal Register / Vol. 52, No. 115 / Tuesday, June 16, 1987 / Proposed Rules 4. In § 61.195, revise paragraph (d) to § 91.24 ATC Transponder and altitude a terminal control area shall comply read as follows: reporting equipment and use. with any procedures established by ***** ATC for such operations in the terminal §61.195 Flight instructor limitations. ***** (b) Controlled airspace: all aircraft. control area. Except for persons operating gliders (b) Pilot requirements. (1) No person (d) Logbook endorsement. He may not above 12,500 feet MSL but below the may take off or land a civil aircraft from endorse a student pilot’s logbook— floor of the positive control area, no an airport within a terminal control area (1) For solo flight unless he has given person may operate an aircraft in the or operate a civil aircraft within a that student flight instruction and found airspace prescribed in (b)(1), (b)(2), or terminal control area unless: that student pilot prepared for solo flight (b)(3) of this section, unless that aircraft in the type of aircraft involved, or for a (1) The pilot-in-command holds at is equipped with an operable coded least a private pilot certificate; or; cross-country flight, and he has radar beacon transponder having a reviewed the student’s flight (ii) The aircraft is operated by a Mode3/A 4096 code capability replying student pilot who has fulfilled the preparation, planning, equipment, and to Mode 3/A interrogations with the requirements of § 61.95. proposed procedures and found them to code specified -

The Bees of Greater Puerto Rico (Hymenoptera: Apoidea: Anthophila)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Insecta Mundi Florida August 2008 The bees of Greater Puerto Rico (Hymenoptera: Apoidea: Anthophila) Julio A. Genaro York University, Toronto, [email protected] Nico M. Franz University of Puerto Rico, Mayagüez, PR, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi Part of the Entomology Commons Genaro, Julio A. and Franz, Nico M., "The bees of Greater Puerto Rico (Hymenoptera: Apoidea: Anthophila)" (2008). Insecta Mundi. 569. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi/569 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Florida at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Insecta Mundi by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. INSECTA MUNDI A Journal of World Insect Systematics 0040 The bees of Greater Puerto Rico (Hymenoptera: Apoidea: Anthophila) Julio A. Genaro Department of Biology, York University 4700 Keele St., Toronto, ON, M3J 1P3, Canada Nico M. Franz Department of Biology, University of Puerto Rico PO Box 9012, Mayagüez, PR 00681, U.S.A. Date of Issue: August 22, 2008 CENTER FOR SYSTEMATIC ENTOMOLOGY, INC., Gainesville, FL Julio A. Genaro and Nico M. Franz The bees of Greater Puerto Rico (Hymenoptera: Apoidea: Anthophila) Insecta Mundi 0040: 1-24 Published in 2008 by Center for Systematic Entomology, Inc. P. O. Box 147100 Gainesville, FL 32614-7100 U. S. A. http://www.centerforsystematicentomology.org/ Insecta Mundi is a journal primarily devoted to insect systematics, but articles can be published on any non-marine arthropod taxon. -

What Is the Evidence That Invasive Species Are a Significant Contributor to the Decline Or Loss of Threatened Species? Philip D

Invasive Species Systematic Review, March 2015 What is the evidence that invasive species are a significant contributor to the decline or loss of threatened species? Philip D. Roberts, Hilda Diaz-Soltero, David J. Hemming, Martin J. Parr, Richard H. Shaw, Nicola Wakefield, Holly J. Wright, Arne B.R. Witt www.cabi.org KNOWLEDGE FOR LIFE Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................. 1 Abstract .................................................................................................................................... 3 Keywords ................................................................................................................................. 4 Definitions ................................................................................................................................ 4 Background .............................................................................................................................. 5 Objective of the review ............................................................................................................ 7 The primary review question: ....................................................................................... 7 Secondary question 1: ................................................................................................. 7 Secondary question 2: ................................................................................................. 7 Methods