The Technological Embodiment of Colonialism in Puerto Rico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reporton the Rare Plants of Puerto Rico

REPORTON THE RARE PLANTS OF PUERTO RICO tii:>. CENTER FOR PLANT CONSERVATION ~ Missouri Botanical Garden St. Louis, Missouri July 15, l' 992 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The Center for Plant Conservation would like to acknowledge the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and the W. Alton Jones Foundation for their generous support of the Center's work in the priority region of Puerto Rico. We would also like to thank all the participants in the task force meetings, without whose information this report would not be possible. Cover: Zanthoxy7um thomasianum is known from several sites in Puerto Rico and the U.S . Virgin Islands. It is a small shrub (2-3 meters) that grows on the banks of cliffs. Threats to this taxon include development, seed consumption by insects, and road erosion. The seeds are difficult to germinate, but Fairchild Tropical Garden in Miami has plants growing as part of the Center for Plant Conservation's .National Collection of Endangered Plants. (Drawing taken from USFWS 1987 Draft Recovery Plan.) REPORT ON THE RARE PLANTS OF PUERTO RICO TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements A. Summary 8. All Puerto Rico\Virgin Islands Species of Conservation Concern Explanation of Attached Lists C. Puerto Rico\Virgin Islands [A] and [8] species D. Blank Taxon Questionnaire E. Data Sources for Puerto Rico\Virgin Islands [A] and [B] species F. Pue~to Rico\Virgin Islands Task Force Invitees G. Reviewers of Puerto Rico\Virgin Islands [A] and [8] Species REPORT ON THE RARE PLANTS OF PUERTO RICO SUMMARY The Center for Plant Conservation (Center) has held two meetings of the Puerto Rlco\Virgin Islands Task Force in Puerto Rico. -

Monocotyledons and Gymnosperms of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Contributions from the United States National Herbarium Volume 52: 1-415 Monocotyledons and Gymnosperms of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands Editors Pedro Acevedo-Rodríguez and Mark T. Strong Department of Botany National Museum of Natural History Washington, DC 2005 ABSTRACT Acevedo-Rodríguez, Pedro and Mark T. Strong. Monocots and Gymnosperms of Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. Contributions from the United States National Herbarium, volume 52: 415 pages (including 65 figures). The present treatment constitutes an updated revision for the monocotyledon and gymnosperm flora (excluding Orchidaceae and Poaceae) for the biogeographical region of Puerto Rico (including all islets and islands) and the Virgin Islands. With this contribution, we fill the last major gap in the flora of this region, since the dicotyledons have been previously revised. This volume recognizes 33 families, 118 genera, and 349 species of Monocots (excluding the Orchidaceae and Poaceae) and three families, three genera, and six species of gymnosperms. The Poaceae with an estimated 89 genera and 265 species, will be published in a separate volume at a later date. When Ackerman’s (1995) treatment of orchids (65 genera and 145 species) and the Poaceae are added to our account of monocots, the new total rises to 35 families, 272 genera and 759 species. The differences in number from Britton’s and Wilson’s (1926) treatment is attributed to changes in families, generic and species concepts, recent introductions, naturalization of introduced species and cultivars, exclusion of cultivated plants, misdeterminations, and discoveries of new taxa or new distributional records during the last seven decades. -

Evaluación De Los Recursos Forestales De Puerto Rico

Department of Natural and Environmental Resources GOVERNMENT OF PUERTO RICO Puerto Rico Statewide Assessment and Strategies for Forest Resources Acknowledgements Many people have contributed to this final edition of the Puerto Rico Statewide Assessment and Strategies for Forest Resources (PRSASFR) in a variety of ways. We gratefully acknowledge the efforts of all those who contributed to this document, through all its stages until this final version. Their efforts have resulted in a comprehensive, forward- looking strategy to keep Puerto Rico‘s forests as healthy natural resources and thriving into the future. Thanks go to the extensive efforts of the hard working staff of the Forest Service Bureau of the Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources (DNER), and the International Institute of Tropical Forestry (IITF), whose joint work have made this PRFASFR possible. Within the DNER, we also want to thank the Comprehensive Planning Area, in particular to its Acting Assistant Secretary Mr. José E. Basora Fagundo for devoting resources under his supervision exclusively for this task. Within ITTF, we want to highlight the immeasurable contribution of the restless editor Ms. Constance Carpenter, who always pushed us to strive for excellence. In addition, we want to thank the Southern Group of State Foresters for their grant supporting many of the maps enclosed and text in the initial stages of this document. We are also grateful to Geographic Consulting LLC, whose collaboration was made possible by sponsorship of IITF, for their wonderful editing work in the previous stages of the document. Thanks also go to particular DNER and IITF staff, to members of the State Technical Committee through its Forest and Wildlife Subcommittee, and to other external professionals, for their particular contributions to and their efforts bringing the PRSASFR together: Editing Contributors: Nicole Balloffet (USFS) Cristina Cabrera (DNER) Constance Carpenter (IITF) Geographic Consulting LLC Magaly Figueroa (IITF) Norma Lozada (DNER) José A. -

Diario De Sesiones

DIARIO DE SESIONES PROCEDIMIENTOS Y DEBATES DE LA ESTADO LIBRE ASOCIADO DE PUERTO RICO ASAMBLEA LEGISLATIVA Vol. XXXIII SAN JUAN, P.R.-Miércoles, 18 de abril de 1979 Núm. 47 SENADO A la una y quince minutos de la tarde de sonar por algún tIempo para ver, entre otras Servicios; para autorizar al Secretario de hoy, miércoles, 18 de abril de 1979 (DIA cosas, que los señores de la Prensa nos querían Hacienda a hacer anticipos a dicho CIENTO UNO DE SESION), el Senado hacer una serie de preguntas y nos retuvieron Departamento y disponer sobre el reanuda sus trabajos bajo la Presidencia del en la antesala del hemiciclo para hacernos reembolso de los mismos; y para señor Miguel A. Miranda, designado al efecto una serie de preguntas relativas a esas vistas. autorizar el pareo de los fondos que se por el Presidente, señor Ferré. y por el otro lado, pues, estábamos esperando asignan." para que llegaran los demás compañeros, si es ASISTENCIA que podian terminar sus labores en la La Comisión de Juventud y Deportes, Comisión. En vista de que está reunida la proponiendo al Senado que se apruebe, con Señora: Comisión de Nombramientos, señor enmiendas,el Benitez Presidente. y exigiendo el Reglamento Señores: del Senado de Puerto Rico, que ninguna P.deIS.818 Calero Juarbe Comisión puede estar reunida mientras el Campos Ayala Senado está constituido para deliberar en su "Para prohibir a toda persona natural o juri Cancel Rios Sesión Ordinaria o Extraordinaria, dica y a todo comerciante, la utilización Deynes Soto formulamos la moción de que se permita a.1a de los distintivos de los Octavos Juegos Señora: Comisión de Nombramientos y a sus Panamericanos a celebrarse próxima• Fernández integrantes continuar con sus vistas públicas, mente en Puerto Rico y del Comité Señores: mientras nosotros despachamos el trabajo Organizador de los Juegos Panamerica Ferré rutinario del Senado. -

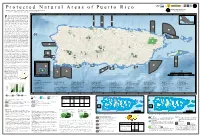

Protected Areas by Management 9

Unted States p Forest Department a Service DRNA of Agriculture g P r o t e c t e d N a t u r a l A r e a s o f P u e r to R i c o K E E P I N G C O M M ON S P E C I E S C O M M O N PRGAP ANALYSIS PROJECT William A. Gould, Maya Quiñones, Mariano Solórzano, Waldemar Alcobas, and Caryl Alarcón IITF GIS and Remote Sensing Lab A center for tropical landscape analysis U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, International Institute of Tropical Forestry . o c 67°30'0"W 67°20'0"W 67°10'0"W 67°0'0"W 66°50'0"W 66°40'0"W 66°30'0"W 66°20'0"W 66°10'0"W 66°0'0"W 65°50'0"W 65°40'0"W 65°30'0"W 65°20'0"W i R o t rotection of natural areas is essential to conserving biodiversity and r e u P maintaining ecosystem services. Benefits and services provided by natural United , Protected areas by management 9 States 1 areas are complex, interwoven, life-sustaining, and necessary for a healthy A t l a n t i c O c e a n 1 1 - 6 environment and a sustainable future (Daily et al. 1997). They include 2 9 0 clean water and air, sustainable wildlife populations and habitats, stable slopes, The Bahamas 0 P ccccccc R P productive soils, genetic reservoirs, recreational opportunities, and spiritual refugia. -

Puerto Rico Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy 2005

Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy Puerto Rico PUERTO RICO COMPREHENSIVE WILDLIFE CONSERVATION STRATEGY 2005 Miguel A. García José A. Cruz-Burgos Eduardo Ventosa-Febles Ricardo López-Ortiz ii Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy Puerto Rico ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Financial support for the completion of this initiative was provided to the Puerto Rico Department of Natural and Environmental Resources (DNER) by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) Federal Assistance Office. Special thanks to Mr. Michael L. Piccirilli, Ms. Nicole Jiménez-Cooper, Ms. Emily Jo Williams, and Ms. Christine Willis from the USFWS, Region 4, for their support through the preparation of this document. Thanks to the colleagues that participated in the Comprehensive Wildlife Conservation Strategy (CWCS) Steering Committee: Mr. Ramón F. Martínez, Mr. José Berríos, Mrs. Aida Rosario, Mr. José Chabert, and Dr. Craig Lilyestrom for their collaboration in different aspects of this strategy. Other colleagues from DNER also contributed significantly to complete this document within the limited time schedule: Ms. María Camacho, Mr. Ramón L. Rivera, Ms. Griselle Rodríguez Ferrer, Mr. Alberto Puente, Mr. José Sustache, Ms. María M. Santiago, Mrs. María de Lourdes Olmeda, Mr. Gustavo Olivieri, Mrs. Vanessa Gautier, Ms. Hana Y. López-Torres, Mrs. Carmen Cardona, and Mr. Iván Llerandi-Román. Also, special thanks to Mr. Juan Luis Martínez from the University of Puerto Rico, for designing the cover of this document. A number of collaborators participated in earlier revisions of this CWCS: Mr. Fernando Nuñez-García, Mr. José Berríos, Dr. Craig Lilyestrom, Mr. Miguel Figuerola and Mr. Leopoldo Miranda. A special recognition goes to the authors and collaborators of the supporting documents, particularly, Regulation No. -

Declining Human Population but Increasing Residential Development Around Protected Areas in Puerto Rico

Biological Conservation 209 (2017) 473–481 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Biological Conservation journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/bioc Declining human population but increasing residential development around protected areas in Puerto Rico J. Castro-Prieto a,c,⁎, S. Martinuzzi b, V.C. Radeloff b,D.P.Helmersb,M.Quiñonesc,W.A.Gouldc a Department of Environmental Sciences, College of Natural Sciences, University of Puerto Rico, PO Box 23341, San Juan 00931-3341, Puerto Rico b SILVIS Lab, Department of Forest and Wildlife Ecology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1630 Linden Drive, Madison, WI 53706, USA c International Institute of Tropical Forestry, USDA Forest Service, 1201 Ceiba Street, Rio Piedras, 00926, Puerto Rico article info abstract Article history: Increasing residential development around protected areas is a major threat for protected areas worldwide, and Received 21 September 2016 human population growth is often the most important cause. However, population is decreasing in many regions Received in revised form 19 January 2017 as a result of socio-economic changes, and it is unclear how residential development around protected areas is Accepted 19 February 2017 affected in these situations. We investigated whether decreasing human population alleviates pressures from Available online xxxx residential development around protected areas, using Puerto Rico—an island with declining population—as a case study. We calculated population and housing changes from the 2000 to 2010 census around 124 protected Keywords: Human-population areas, using buffers of different sizes. We found that the number of houses around protected areas continued to Island increase while population declined both around protected areas and island-wide. -

Beyond the Critique of Rights: the Puerto Rico Legal Project and Civil Rights Litigation in America’S Colony Abstract

VALERIA M. PELET DEL TORO Beyond the Critique of Rights: The Puerto Rico Legal Project and Civil Rights Litigation in America’s Colony abstract. Long skeptical of the ability of rights to advance oppressed groups’ political goals, Critical Legal Studies (CLS) scholars might consider a U.S. territory like Puerto Rico and ask, “What good are rights when you live in a colony?” In this Note, I will argue that CLS’s critique of rights, though compelling in the abstract, falters in the political and historical context of Puerto Rico. Although it may appear that rights have failed Puerto Ricans, rights talk has historically provided a framework for effective organizing and community action. Building on the work of Critical Race Theory and LatCrit scholars, this Note counters the CLS intuition that rights talk lacks value by focusing on the origins and development of the Puerto Rico Legal Project, an un- derstudied but critical force for community development and legal advocacy on the island that was founded in response to severe political repression during the late 1970s and early 1980s. This Note draws on original interviews with Puerto Rican and U.S. lawyers and community activists to reveal fissures in the critique of rights and to propose certain revisions to the theory. By concentrating on the entitlements that rights are thought to provide, CLS’s critique of rights ignores the power of rights discourse to organize marginalized communities. The critique of rights also overlooks the value of the collective efforts that go into articulating a particular community’s aspirations through rights talk, efforts which can be empowering andhelp spur further political action. -

LANGUAGE and IDENTITY in the CERRO MARAVILLA HEARINGS by Germán Negrón Rivera

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by D-Scholarship@Pitt WHAT DID THEY SAY IN THE HALL OF THE DEAD? LANGUAGE AND IDENTITY IN THE CERRO MARAVILLA HEARINGS by Germán Negrón Rivera B.A. University of Puerto Rico, 1988 M.A. University of Puerto Rico, 1997 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2010 ii UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH FACULTY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Germán Negrón Rivera It was defended on April 16, 2010 and approved by Susan Berk-Seligson, Associate Professor, Spanish and Portuguese Department, Vanderbilt University Juan Duchesne Winter, Professor, Department of Hispanic Languages and Literatures Barbara Johnstone, Professor, English Department, Carnegie Mellon University Dissertation Advisor: Scott Kiesling, Associate Professor, Department of Linguistics ii Copyright © by Germán Negrón Rivera 2010 iii WHAT DID THEY SAY IN THE HALL OF THE DEAD? LANGUAGE AND IDENTITY IN THE CERRO MARAVILLA HEARINGS Germán Negrón Rivera, Ph.D. University of Pittsburgh, 2010 Identity has become a major interest for researchers in the areas of linguistic anthropology and sociolinguistics. Recent understandings of identity emphasize its malleability and fluidity. This conceptualization of identities as malleable comes from the realization that speakers relate strategically to propositions and their interlocutors in order to achieve their communicative goals. This study is an exploration of the (co-)construction of identities in an institutional context, specifically in the Cerro Maravilla hearings. I examine the interactions between the Senate‘s main investigator, Héctor Rivera Cruz, and five witnesses in order to explore how identities were created and how speakers managed the interactions. -

Cook's Holly (Ilex Cookii)

Cook’s Holly (Ilex cookii) Image of the type specimen from the Herbarium of the New York Botanical Garden 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Caribbean Ecological Services Field Office Boquerón, Puerto Rico 5-YEAR REVIEW Cook’s Holly / Ilex cookii I. GENERAL INFORMATION A. Methodology used to complete the review: On April 9, 2010, the Service published a notice in the Federal Register announcing the 5-year review of Cook’s holly (Ilex cookii) and requested new information concerning the biology and status of the species (75 FR 18232). A 60-day comment period was opened. No comment letters were received from the public during this period. This 5-year review was finalized by a Service biologist and summarizes the information that the Service has gathered in the Cook’s holly file since the plant was listed on June 16, 1987. The sources of information used for this review included the original listing rule for the species, the recovery plan for Cook’s holly, and information provided by the University of Puerto Rico, Mayagüez Campus (UPRM). Under cooperative agreement with the Service, professors from UPRM, Dr. Duane A. Kolterman and Dr. Jesús D. Chinea, provided to the Service a draft 5-year review compiling all available information on Cook’s holly. They conducted literature research on the species, consulted with other specialists, and examined herbarium data from the University of Puerto Rico at Mayaguez (MAPR), Río Piedras Botanical Garden (UPR), University of Puerto Rico at Río Piedras (UPRRP), Department of Natural and Environmental Resources of Puerto Rico (SJ), New York Botanical Garden (NY), US National Herbarium (US), and University of Illinois (ILL). -

Copyright by Samuel Ellis Ginsburg 2018

Copyright by Samuel Ellis Ginsburg 2018 The Dissertation Committee for Samuel Ellis Ginsburg Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Cyborg Caribbean: Bodies, Technology, and the Struggle for (Post)Humanity in 21st-Century Cuban, Dominican, and Puerto Rican Science Fiction Committee: Jossianna Arroyo- Martínez, Co-Supervisor César Salgado, Co-Supervisor Luís Cárcamo Huechante John Morán González The Cyborg Caribbean: Bodies, Technology and the Struggle for (Post)Humanity in 21st-Century Cuban, Dominican, and Puerto Rican Science Fiction By Samuel Ellis Ginsburg Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2018 Acknowledgements I would first like to acknowledge my dissertation committee for their support of this project: Co-Supervisors Jossianna Arroyo-Martínez and César Salgado, and committee members Luís Cárcamo Huechante and John Morán Gonazález. Each one has helped shape my academic and personal trajectory. Thank you for not kicking me out of your offices when I proposed this project. So many of my colleagues have provided me with scholarly and emotional support throughout this process: María Cristina Monsalve, Melissa González Contreras, Ginette Eldridge, James Staig, Valeria Rey de Castro, José Ignacio Carvajal, Sam Cannon, Ruth Rubio, Ana Cecilia Calle, Ana Almar, Stephanie Malak, and Min Suk Kim. I’d also like to thank Laura Rodríguez for making everything possible. My family has been incredibly supportive and have believed in me at every step along the way. Thank you, Mom, Dad, and Ruthie. -

Villanueva-Rivera, L. J. 2006

CALLING ACTIVITY OF ELEUTHERODACTYLUS FROGS OF PUERTO RICO AND HABITAT DISTRIBUTION OF E. RICHMONDI by Luis J. Villanueva Rivera A thesis submitted to the Department of Biology COLLEGE OF NATURAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF PUERTO RICO RIO PIEDRAS CAMPUS In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN BIOLOGY MAY 2006 SAN JUAN, PUERTO RICO © 2006 Luis J. Villanueva Rivera A mi familia iii Acknowledgements I thank my family for their support and encouragement during these years. I also want to thank my thesis committee, J. Thomlinson, T. M. Aide, A. Sabat, and R. Thomas, for their help and suggestions. For sharing data I am grateful to A. Puente, N. Ríos, J. Delgado, and V. Cuevas. For insightful discussions I thank N. Ríos, M. Acevedo, J. Thomlinson, and T. M. Aide. For suggestions that resulted in the first chapter in its current form, I thank C. Restrepo, C. Monmany, and H. Perotto. This research was conducted under the authorization of the Department of Natural and Environmental Resources of Puerto Rico (permit #02-IC-068) and the United States Forest Service (permit #CNF-2038). Part of this research was funded thanks to a fellowship from the “Attaining Research Extensive University Status in Puerto Rico: Building a Competitive Infrastructure” award from the National Science Foundation (#0223152) to the Experimental Program to Stimulate Competitive Research at the University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras Campus. I also thank the Department of Biology, the Deanship of Graduate Studies and Research, and the CREST- Center for Applied Tropical Ecology and Conservation of the University of Puerto Rico, Río Piedras Campus, for their support by providing several research and teaching assistantships.