A Legacy of the Propaganda: the Tripartite View of Philippine History by Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colonial Contractions: the Making of the Modern Philippines, 1565–1946

Colonial Contractions: The Making of the Modern Philippines, 1565–1946 Colonial Contractions: The Making of the Modern Philippines, 1565–1946 Vicente L. Rafael Subject: Southeast Asia, Philippines, World/Global/Transnational Online Publication Date: Jun 2018 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.268 Summary and Keywords The origins of the Philippine nation-state can be traced to the overlapping histories of three empires that swept onto its shores: the Spanish, the North American, and the Japanese. This history makes the Philippines a kind of imperial artifact. Like all nation- states, it is an ineluctable part of a global order governed by a set of shifting power rela tionships. Such shifts have included not just regime change but also social revolution. The modernity of the modern Philippines is precisely the effect of the contradictory dynamic of imperialism. The Spanish, the North American, and the Japanese colonial regimes, as well as their postcolonial heir, the Republic, have sought to establish power over social life, yet found themselves undermined and overcome by the new kinds of lives they had spawned. It is precisely this dialectical movement of empires that we find starkly illumi nated in the history of the Philippines. Keywords: Philippines, colonialism, empire, Spain, United States, Japan The origins of the modern Philippine nation-state can be traced to the overlapping histo ries of three empires: Spain, the United States, and Japan. This background makes the Philippines a kind of imperial artifact. Like all nation-states, it is an ineluctable part of a global order governed by a set of shifting power relationships. -

Tagalog Support for Languagetool

Tagalog Support for LanguageTool Nathaniel Oco Allan Borra De La Salle University - Manila De La Salle University - Manila 2401 Taft Avenue Malate, Manila City 2401 Taft Avenue Malate, Manila City 1004 Metro Manila, Philippines 1004 Metro manila, Philippines +639178477549 +639174591073 [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT 25, 2011, already includes Tagalog support. This paper outlines the different processes and issues involved in Aside from Tagalog, LanguageTool also supports Asturian, adding a Tagalog support for LanguageTool. LanguageTool is an Belarusian, Breton, Catalan, Chinese, Czech, Danish, Dutch, open-source rule-based style and grammar checker that English, Esperanto, French, Galician, Icelandic, Italian, Khmer, implements a manual-based rule-creation approach. Details of the Lithuanian, Malayalam, Polish, Russian, Slovak, Slovenian, different LanguageTool resources are discussed in this paper. The Spanish, Swedish, Ukrainian, and Romanian. different linguistic considerations, technical considerations, and language properties of Tagalog – that were captured and handled This paper aims to explain the processes and issues involved in – are also discussed and outlined. The system was tested using 50 adding a new language support – Tagalog support – for correct and 50 incorrect sentences collected from different LanguageTool. sources. LanguageTool processed the correct sentences in 53 milliseconds and the incorrect sentences in 80 milliseconds. The 2. GRAMMAR CHECKING Tagalog support scored 95.83% for precision, 46% for recall, and Grammar Checking is the process of detecting if there is error in 72% for accuracy. an input. Mark Johnson [Johnson, personal communication] added that grammar checking entails locating where the error is Categories and Subject Descriptors and notifying the user about the error. -

The La Solidaridad and Philippine Journalism in Spain (1889-1895)

44 “Our Little Newspaper”… “OUR LITTLE NEWSPAPER” THE LA SOLIDARIDAD AND PHILIPPINE JOURNALISM IN SPAIN (1889-1895) Jose Victor Z. Torres, PhD De La Salle University-Manila [email protected] “Nuestros periodiquito” or “Our little newspaper” Historian, archivist, and writer Manuel Artigas y was how Marcelo del Pilar described the periodical Cuerva had written works on Philippine journalism, that would serve as the organ of the Philippine especially during the celebration of the tercentenary reform movement in Spain. For the next seven years, of printing in 1911. A meticulous researcher, Artigas the La Solidaridad became the respected Philippine newspaper in the peninsula that voiced out the viewed and made notes on the pre-war newspaper reformists’ demands and showed their attempt to collection in the government archives and the open the eyes of the Spaniards to what was National Library. One of the bibliographical entries happening to the colony in the Philippines. he wrote was that of the La Solidaridad, which he included in his work “El Centenario de la Imprenta”, But, despite its place in our history, the story of a series of articles in the American period magazine the La Solidaridad has not entirely been told. Madalas Renacimiento Filipino which ran from 1911-1913. pag-usapan pero hindi alam ang kasaysayan. We do not know much of the La Solidaridad’s beginnings, its Here he cited a published autobiography by reformist struggle to survive as a publication, and its sad turned revolutionary supporter, Timoteo Paez as his ending. To add to the lacunae of information, there source. -

The Nineteenth-Century Thomist from the Far East:

The Nineteenth-Century Thomist from theF ar East: Cardinal Zeferino González, OP (1831–1894) Levine Andro H. Lao1 Center for Theology, Religious Studies and Ethics University of Santo Tomás, Manila, Philippines Abstract: In light of the celebration of the five centuries of Christianity in the Philippines, this article hopes to reintroduce Fr. Zeferino González, OP, to scholars of Church history, philosophy, and cultural heritage. He was an alumnus of the University of Santo Tomás, a Cardinal, and a champion of the revival of Catholic Philosophy that led to the promulgation of Leo XIII’s encyclical Aeterni Patris. Specifically, this essay presents, firstly, the Cardinal’s biography in the context of his experience as a missionary in the Philippines; secondly, the intellectual tradition in Santo Tomás in Manila, which he carried with him until his death; and lastly, some reasons for his once-radiant memory to slip into an undeserved forgetfulness. Keywords: Zeferino González, Thomism in Asia, Aeterni Patris, Christian Philosophy, History of Philosophy n the 1880s, the University of Santo Tomás had two grand celebrations that were associated with Fr. Zeferino González, OP (1831–1894). The first pompous festivity was held in 1880 when the University received Pope Leo XIII’s encyclical Aeterni Patris;2 the second was when Fray Zeferino (as how I1 Levine Andro Hernandez Lao can be contacted at [email protected]. He teaches at the Ecclesiastical Faculty of Philosophy, University of Santo Tomas, Manila. https://orcid.org/0000- 0002-1136-2432. This study was funded by the 2020 National Research Award given by the National Commission for Culture and Arts (Philippines). -

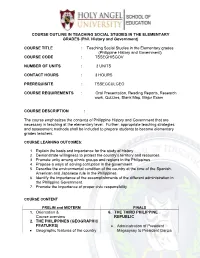

COURSE OUTLINE in TEACHING SOCIAL STUDIES in the ELEMENTARY GRADES (Phil

COURSE OUTLINE IN TEACHING SOCIAL STUDIES IN THE ELEMENTARY GRADES (Phil. History and Government) COURSE TITLE : Teaching Social Studies in the Elementary grades (Philippine History and Government) COURSE CODE : TSSEGHISGOV NUMBER OF UNITS : 3 UNITS CONTACT HOURS : 3 HOURS PREREQUISITE : TSSEGCULGEO COURSE REQUIREMENTS : Oral Presentation, Reading Reports, Research work, Quizzes, Blank Map, Major Exam COURSE DESCRIPTION : The course emphasizes the contents of Philippine History and Government that are necessary in teaching at the elementary level. Further, appropriate teaching strategies and assessment methods shall be included to prepare students to become elementary grades teachers. COURSE LEARNING OUTCOMES: 1. Explain the basis and importance for the study of history. 2. Demonstrate willingness to protect the country’s territory and resources. 3. Promote unity among ethnic groups and regions in the Philippines 4. Propose a ways of solving corruption in the government 5. Describe the environmental condition of the country at the time of the Spanish, American and Japanese rule in the Philippines. 6. Identify the importance of the accomplishments of the different administration in the Philippine Government. 7. Promote the importance of proper civic responsibility COURSE CONTENT PRELIM and MIDTERM FINALS 1. Orientation & 6. THE THIRD PHILIPPINE Course overview REPUBLIC 2. THE PHILIPPINES (GEOGRAPHIC FEATURES) Administration of President Geographic features of the country Magsaysay to President Garcia Natural resources Regions of the Philippine Administration of President Profile of the Filipinos as a People Macapagal and President Marcos 3. PRE SPANISH PERIOD 7. THE FOURTH REPUBLIC The first Filipinos (MARTIAL LAW PERIOD) Ancestors’ cultures and way of life The Declaration of Martial Law The arrival and spread of Islam The end of Military Rule 4. -

Dissertations, Department of Linguistics

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics Title Reflexivization: A Study in Universal Syntax Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3sv079tk Author Faltz, Leonard M Publication Date 1977 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph end reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will finda good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. -

Phrase Structure and Grammatical Relations in Tagalog

Phrase Structure and Grammatical Relations in Tagalog Paul R. Kroeger Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Linguistics Stanford University August, 1991 (Note: some corrections and other minor editorial changes are included in this version, but the list of references has unfortunately been lost.) Abstract This dissertation presents an analysis of Tagalog within the framework of Lexical-Functional Grammar. Tagalog is a non-configurational language in which the grammatical subject does not occupy a unique structural position. Nevertheless, the grammar of Tagalog makes crucial reference to the notion of grammatical subjecthood. This fact shows that grammatical subjecthood cannot be defined in terms of a specified position in surface phrase structure. More generally, the Tagalog data shows that grammatical relations must be defined independently of phrase structure, semantic structure and pragmatic functions, strongly supporting a conception of linguistic structure in which these various kinds of information are modeled as independent subsystems of the grammar. A large number of syntactic tests are presented which uniquely identify the nominative argument as the grammatical subject. It is argued that the apparent ambiguity of subjecthood properties in Tagalog is due to the Actor’s semantic and pragmatic prominence, together with the fact that non-subject Actors are always terms (non-oblique arguments) in Tagalog, unlike passive agents in English. Evidence is presented which shows that the nominative argument does not have the properties of a “topic”, as it is frequently analyzed, whether this concept is defined in terms of discourse continuity or pragmatic function. Crucial evidence for the non-configurationality of Tagalog comes from rules governing the co-reference of personal pronouns and the position of clitic elements. -

Roberto BLANCO ANDRÉS, Los Sucesos De Antique De 1888, Pp. 7

Arch Ag 99 (2015) 7-63 Los sucesos de Antique de 1888 POR ROBERTO BLANCO ANDRÉS En los meses de mayo y junio de 1888 estalló una rebelión an - tiespañola e independentista en la provincia de Antique (isla de Panay, Filipinas). El levantamiento no tuvo ninguna conexión con el movimiento nacionalista de los ilustrados filipinos de La Propaganda. Ocurrió en una provincia con escasa población española y de tradi - cional administración de la Orden de San Agustín. En este artículo se realiza un estudio en profundidad de unos sucesos prácticamente des - conocidos para la bibliografía, indagando en sus causas, objetivos, desarrollo y protagonistas. Para ello se ha transcrito la correspon - dencia inédita del Padre Alipio Azpitarte, vicario provincial agustino en Antique, quien en las comunicaciones con su superior provincial aporta una información muy rica y abundante. In the months of May and June 1888 broke out an anti-spanish and independentist rebellion in the province of Antique (island of Panay, Philippines). The uprising had no connection with the nationa - list movement of Filipino “Ilustrados” of La Propaganda. It happened in a province with very few spanish and traditionally administered by the Order of St Augustin. We offer in this article a depth study about events virtually unknown, doing a study of its causes, objectives and protagonists. For this purpose we have transcribed the unpublished co - rrespondence of Fr. Alipio Azpitarte, Provincial Vicar Augustinian of Antique, who in their communications with their provincial superior provides a rich and abundant information. Diez años antes del final del dominio hispánico en Filipinas estalló una insurrección en Antique contra los españoles de esa provincia ubicada en 8 R. -

UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Language, Tagalog Regionalism, and Filipino Nationalism: How a Language-Centered Tagalog Regionalism Helped to Develop a Philippine Nationalism Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/69j3t8mk Author Porter, Christopher James Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Language, Tagalog Regionalism, and Filipino Nationalism: How a Language-Centered Tagalog Regionalism Helped to Develop a Philippine Nationalism A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Southeast Asian Studies by Christopher James Porter June 2017 Thesis Committee: Dr. Hendrik Maier, Chairperson Dr. Sarita See Dr. David Biggs Copyright by Christopher James Porter 2017 The Thesis of Christopher James Porter is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Table of Contents: Introduction………………………………………………….. 1-4 Part I: Filipino Nationalism Introduction…………………………………………… 5-8 Spanish Period………………………………………… 9-21 American Period……………………………………… 21-28 1941 to Present……………………………………….. 28-32 Part II: Language Introduction…………………………………………… 34-36 Spanish Period……………………………………….... 36-39 American Period………………………………………. 39-43 1941 to Present………………………………………... 44-51 Part III: Formal Education Introduction…………………………………………… 52-53 Spanish Period………………………………………… 53-55 American Period………………………………………. 55-59 1941 to 2009………………………………………….. 59-63 A New Language Policy……………………………… 64-68 Conclusion……………………………………………………. 69-72 Epilogue………………………………………………………. 73-74 Bibliography………………………………………………….. 75-79 iv INTRODUCTION: The nation-state of the Philippines is comprised of thousands of islands and over a hundred distinct languages, as well as over a thousand dialects of those languages. The archipelago has more than a dozen regional languages, which are recognized as the lingua franca of these different regions. -

Race and Ethnicity in the Era of the Philippine-American War, 1898-1914

Allegiance and Identity: Race and Ethnicity in the Era of the Philippine-American War, 1898-1914 by M. Carmella Cadusale Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the History Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY August, 2016 Allegiance and Identity: Race and Ethnicity in the Era of the Philippine-American War, 1898-1914 M. Carmella Cadusale I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: M. Carmella Cadusale, Student Date Approvals: Dr. L. Diane Barnes, Thesis Advisor Date Dr. David Simonelli, Committee Member Date Dr. Helene Sinnreich, Committee Member Date Dr. Salvatore A. Sanders, Dean of Graduate Studies Date ABSTRACT Filipino culture was founded through the amalgamation of many ethnic and cultural influences, such as centuries of Spanish colonization and the immigration of surrounding Asiatic groups as well as the long nineteenth century’s Race of Nations. However, the events of 1898 to 1914 brought a sense of national unity throughout the seven thousand islands that made the Philippine archipelago. The Philippine-American War followed by United States occupation, with the massive domestic support on the ideals of Manifest Destiny, introduced the notion of distinct racial ethnicities and cemented the birth of one national Philippine identity. The exploration on the Philippine American War and United States occupation resulted in distinguishing the three different analyses of identity each influenced by events from 1898 to 1914: 1) The identity of Filipinos through the eyes of U.S., an orientalist study of the “us” versus “them” heavily influenced by U.S. -

Philippine History and Government

Remembering our Past 1521 – 1946 By: Jommel P. Tactaquin Head, Research and Documentation Section Veterans Memorial and Historical Division Philippine Veterans Affairs Office The Philippine Historic Past The Philippines, because of its geographical location, became embroiled in what historians refer to as a search for new lands to expand European empires – thinly disguised as the search for exotic spices. In the early 1400’s, Portugese explorers discovered the abundance of many different resources in these “new lands” heretofore unknown to early European geographers and explorers. The Portugese are quickly followed by the Dutch, Spaniards, and the British, looking to establish colonies in the East Indies. The Philippines was discovered in 1521 by Portugese explorer Ferdinand Magellan and colonized by Spain from 1565 to 1898. Following the Spanish – American War, it became a territory of the United States. On July 4, 1946, the United States formally recognized Philippine independence which was declared by Filipino revolutionaries from Spain. The Philippine Historic Past Although not the first to set foot on Philippine soil, the first well document arrival of Europeans in the archipelago was the Spanish expedition led by Portuguese Ferdinand Magellan, which first sighted the mountains of Samara. At Masao, Butuan, (now in Augustan del Norte), he solemnly planted a cross on the summit of a hill overlooking the sea and claimed possession of the islands he had seen for Spain. Magellan befriended Raja Humabon, the chieftain of Sugbu (present day Cebu), and converted him to Catholicism. After getting involved in tribal rivalries, Magellan, with 48 of his men and 1,000 native warriors, invaded Mactan Island. -

Grammar and Information Structure a Study with Reference to Russian

Grammar and Information Structure a study with reference to Russian Published by LOT Janskerkhof 13 3512 BL Utrecht The Netherlands phone: +31 30 253 6006 fax: +31 30 253 6406 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.lotschool.nl Cover illustration by Ilya Ruderman ISBN 978-90-78328-32-2 NUR 616 Copyright © 2007: Natalia Slioussar. All rights reserved. Grammar and Information Structure a study with reference to Russian Grammatica en Informatiestructuur een studie met betrekking tot het Russisch (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof.dr. W.H. Gispen, ingevolge het besluit van het college voor promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op woensdag 4 juli 2007 des ochtends te 10.30 uur door Natalia Slioussar geboren op 16 november 1980 te Sint-Petersburg, Russische Federatie Promotoren: prof.dr. E.J. Reuland prof.dr. F.N.K. Wijnen prof.dr. T.V. Chernigovskaya Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................ix 1 Introduction ........................................................................................1 1.1 What does the grammatical IS system encode and how? ...........4 1.1.1 IS notions in the grammar elude definition................................4 1.1.2 Activation network model of the discourse IS system .................6 1.1.3 Discourse IS notions in the activation network model ................8 1.1.4 From discourse to syntax: what is encoded and how? ..............11