UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE PHILIPPINES, 1942-1944 James Kelly Morningstar, Doctor of History

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: WAR AND RESISTANCE: THE PHILIPPINES, 1942-1944 James Kelly Morningstar, Doctor of History, 2018 Dissertation directed by: Professor Jon T. Sumida, History Department What happened in the Philippine Islands between the surrender of Allied forces in May 1942 and MacArthur’s return in October 1944? Existing historiography is fragmentary and incomplete. Memoirs suffer from limited points of view and personal biases. No academic study has examined the Filipino resistance with a critical and interdisciplinary approach. No comprehensive narrative has yet captured the fighting by 260,000 guerrillas in 277 units across the archipelago. This dissertation begins with the political, economic, social and cultural history of Philippine guerrilla warfare. The diverse Islands connected only through kinship networks. The Americans reluctantly held the Islands against rising Japanese imperial interests and Filipino desires for independence and social justice. World War II revealed the inadequacy of MacArthur’s plans to defend the Islands. The General tepidly prepared for guerrilla operations while Filipinos spontaneously rose in armed resistance. After his departure, the chaotic mix of guerrilla groups were left on their own to battle the Japanese and each other. While guerrilla leaders vied for local power, several obtained radios to contact MacArthur and his headquarters sent submarine-delivered agents with supplies and radios that tie these groups into a united framework. MacArthur’s promise to return kept the resistance alive and dependent on the United States. The repercussions for social revolution would be fatal but the Filipinos’ shared sacrifice revitalized national consciousness and created a sense of deserved nationhood. The guerrillas played a key role in enabling MacArthur’s return. -

Rf Revista Filipina, Segunda Etapa: Revistainvierno Filipina 2013–P, Rimaverasegunda 2014 Etapa : Inviernovol 2013

Revista Filipina • Invierno 2013 / Primavera 2014 Vol. 1, Número 1 RF Revista 4Filipina Invierno 2013 / Primavera 2014 Volumen 1, Número 2 Revista semestral de lengua y literatura hispanofilipina http://revista.carayanpress.com Dirigida por Edmundo Farolán desde 1997. ISSN: 1496-4538 Segunda Etapa RF Comité editorial: Director: Edmundo Farolán Subdirector: Isaac Donoso Secretario: Andrea Gallo Webmáster: Edwin Lozada Redacción: Jorge Molina, David Manzano y Jeannifer Zabala Comité científico: Pedro Aullón de Haro Florentino Rodao Universidad de Alicante Universidad Complutense de Madrid Joaquín García Medall Joaquín Sueiro Justel Universidad de Valladolid Universidad de Vigo Guillermo Gómez Rivera Fernando Ziálcita Academia Filipina de la Lengua Española Universidad Ateneo de Manila Copyright © 2013 Edmundo Farolán, Revista Filipina Fotografía de la portada: Fuerte de Santiago, Intramuros, Edwin Lozada 1 Revista Filipina • Invierno 2013 / Primavera 2014 Vol. 1, Número 1 RF EDITORIAL Queridos amigos y lectores, Edmundo Farolán se encuentra viajando y me ha pedido que redacte unas líneas de presentación de este número, que constituye el segundo de nuestra Segunda Etapa. Ciertamente la voluntad de Revista Filipina es seguir contribuyendo a la discusión académica de la cultura filipina, y hacer accesibles para la comunidad científica —gracias a las posibilidades de los nuevos medios de difusión— materiales imprescindibles en los Estudios Filipinos. Con esta vocación nace la sección de «Biblioteca», que pretende ofrecer dos tipos de textos: bien la recuperación filológica, literaria o lingüística de obras fundamentales del corpus filipino, a través de ediciones modernas; o bien la publicación de obras novedosas, que por su tema contribuyan de forma original a la bibliografía filipinista. En este sentido inauguramos la sección publicando la primera edición que se realiza del famoso Boxer Codex. -

Reflections on Agoncilloʼs the Revolt of the Masses and the Politics of History

Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 49, No. 3, December 2011 Reflections on Agoncilloʼs The Revolt of the Masses and the Politics of History Reynaldo C. ILETO* Abstract Teodoro Agoncilloʼs classic work on Andres Bonifacio and the Katipunan revolt of 1896 is framed by the tumultuous events of the 1940s such as the Japanese occupation, nominal independence in 1943, Liberation, independence from the United States, and the onset of the Cold War. Was independence in 1946 really a culmination of the revolution of 1896? Was the revolution spearheaded by the Communist-led Huk movement legitimate? Agoncilloʼs book was written in 1947 in order to hook the present onto the past. The 1890s themes of exploitation and betrayal by the propertied class, the rise of a plebeian leader, and the revolt of the masses against Spain, are implicitly being played out in the late 1940s. The politics of hooking the present onto past events and heroic figures led to the prize-winning manuscriptʼs suppression from 1948 to 1955. Finally seeing print in 1956, it provided a novel and timely reading of Bonifacio at a time when Rizalʼs legacy was being debated in the Senate and as the Church hierarchy, priests, intellectuals, students, and even general public were getting caught up in heated controversies over national heroes. The circumstances of how Agoncilloʼs work came to the attention of the author in the 1960s are also discussed. Keywords: Philippine Revolution, Andres Bonifacio, Katipunan society, Cold War, Japanese occupation, Huk rebellion, Teodoro Agoncillo, Oliver Wolters Teodoro Agoncilloʼs The Revolt of the Masses: The Story of Bonifacio and the Katipunan is one of the most influential books on Philippine history. -

Un Mundo Ilustrado

UN MUNDO ILUSTRADO José Rizal formó parte del mundo ilustrado que floreció en Filipinas a fines del siglo XIX. En él se incluía una élite de personas educadas en universidades filipinas, que frecuentemente completaban su formación en instituciones europeas. Este grupo de ilustrados, identificados más por su grado de educación que por un único nivel socioeconómico, fue esencial en la formación de una conciencia nacional filipina. Ilustrados fueron pintores como Juan Luna y Novicio o Félix Resurrección Hidalgo, formados en las notables escuelas de dibujo existentes en Manila y especializados en Academias de Bellas Artes europeas. La destreza de sus pinceles les llevó a ganar importantes certámenes internacionales. Los ilustrados se interesaron también por el estudio de la Lengua, bien fuera a través de investigaciones sobre los antiguos alfabetos filipinos o los muchos dialectos del archipiélago, bien a través del aprendizaje de los idiomas modernos. Tenían tras ellos, además, una larga tradición de elaboración de gramáticas, iniciada por los religiosos españoles en 1610, cuando Fr. Joseph publicó en Filipinas la primera gramática tagala. Posteriormente, otros autores estudiaron el visayo, el pampago, el ilocano… Rizal insertó sus estudios gramaticales, que abarcaron desde el tagalo a los jeroglíficos egipcios, pasando por más de diez lenguas, en esa tradición. Algo parecido ocurrió con el conocimiento de la Historia. Desde el siglo XVI se escribieron importantes estudios históricos sobre el archipiélago – Chirino, 1604; Colín, 1663; San Agustín, 1698; Aduarte, 1693… – Rizal prosiguió esa dinámica, anotando los Sucesos de Filipinas escritos por Antonio de Morga en 1609, en lo que se ha considerado como la primera historia de las islas escrita por un filipino. -

Colonial Contractions: the Making of the Modern Philippines, 1565–1946

Colonial Contractions: The Making of the Modern Philippines, 1565–1946 Colonial Contractions: The Making of the Modern Philippines, 1565–1946 Vicente L. Rafael Subject: Southeast Asia, Philippines, World/Global/Transnational Online Publication Date: Jun 2018 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.268 Summary and Keywords The origins of the Philippine nation-state can be traced to the overlapping histories of three empires that swept onto its shores: the Spanish, the North American, and the Japanese. This history makes the Philippines a kind of imperial artifact. Like all nation- states, it is an ineluctable part of a global order governed by a set of shifting power rela tionships. Such shifts have included not just regime change but also social revolution. The modernity of the modern Philippines is precisely the effect of the contradictory dynamic of imperialism. The Spanish, the North American, and the Japanese colonial regimes, as well as their postcolonial heir, the Republic, have sought to establish power over social life, yet found themselves undermined and overcome by the new kinds of lives they had spawned. It is precisely this dialectical movement of empires that we find starkly illumi nated in the history of the Philippines. Keywords: Philippines, colonialism, empire, Spain, United States, Japan The origins of the modern Philippine nation-state can be traced to the overlapping histo ries of three empires: Spain, the United States, and Japan. This background makes the Philippines a kind of imperial artifact. Like all nation-states, it is an ineluctable part of a global order governed by a set of shifting power relationships. -

"Patria É Intereses": Reflections on the Origins and Changing Meanings of Ilustrado

3DWULD«LQWHUHVHV5HIOHFWLRQVRQWKH2ULJLQVDQG &KDQJLQJ0HDQLQJVRI,OXVWUDGR Caroline Sy Hau Philippine Studies, Volume 59, Number 1, March 2011, pp. 3-54 (Article) Published by Ateneo de Manila University DOI: 10.1353/phs.2011.0005 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/phs/summary/v059/59.1.hau.html Access provided by University of Warwick (5 Oct 2014 14:43 GMT) CAROLINE SY Hau “Patria é intereses” 1 Reflections on the Origins and Changing Meanings of Ilustrado Miguel Syjuco’s acclaimed novel Ilustrado (2010) was written not just for an international readership, but also for a Filipino audience. Through an analysis of the historical origins and changing meanings of “ilustrado” in Philippine literary and nationalist discourse, this article looks at the politics of reading and writing that have shaped international and domestic reception of the novel. While the novel seeks to resignify the hitherto class- bound concept of “ilustrado” to include Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs), historical and contemporary usages of the term present conceptual and practical difficulties and challenges that require a new intellectual paradigm for understanding Philippine society. Keywords: rizal • novel • ofw • ilustrado • nationalism PHILIPPINE STUDIES 59, NO. 1 (2011) 3–54 © Ateneo de Manila University iguel Syjuco’s Ilustrado (2010) is arguably the first contemporary novel by a Filipino to have a global presence and impact (fig. 1). Published in America by Farrar, Straus and Giroux and in Great Britain by Picador, the novel has garnered rave reviews across Mthe Atlantic and received press coverage in the Commonwealth nations of Australia and Canada (where Syjuco is currently based). -

NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION Child & Youth Welfare (Residential) ACCREDITED a HOME for the ANGELS CHILD Mrs

Directory of Social Welfare and Development Agencies (SWDAs) with VALID REGISTRATION, LICENSED TO OPERATE AND ACCREDITATION per AO 16 s. 2012 as of March, 2015 Name of Agency/ Contact Registration # License # Accred. # Programs and Services Service Clientele Area(s) of Address /Tel-Fax Nos. Person Delivery Operation Mode NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION Child & Youth Welfare (Residential) ACCREDITED A HOME FOR THE ANGELS CHILD Mrs. Ma. DSWD-NCR-RL-000086- DSWD-SB-A- adoption and foster care, homelife, Residentia 0-6 months old NCR CARING FOUNDATION, INC. Evelina I. 2011 000784-2012 social and health services l Care surrendered, 2306 Coral cor. Augusto Francisco Sts., Atienza November 21, 2011 to October 3, 2012 abandoned and San Andres Bukid, Manila Executive November 20, 2014 to October 2, foundling children Tel. #: 562-8085 Director 2015 Fax#: 562-8089 e-mail add:[email protected] ASILO DE SAN VICENTE DE PAUL Sr. Enriqueta DSWD-NCR RL-000032- DSWD-SB-A- temporary shelter, homelife Residentia residential care -5- NCR No. 1148 UN Avenue, Manila L. Legaste, 2010 0001035-2014 services, social services, l care and 10 years old (upon Tel. #: 523-3829/523-5264/522- DC December 25, 2013 to June 30, 2014 to psychological services, primary community-admission) 6898/522-1643 Administrator December 24, 2016 June 29, 2018 health care services, educational based neglected, Fax # 522-8696 (Residential services, supplemental feeding, surrendered, e-mail add: [email protected] Care) vocational technology program abandoned, (Level 2) (commercial cooking, food and physically abused, beverage, transient home) streetchildren DSWD-SB-A- emergency relief - vocational 000410-2010 technology progrm September 20, - youth 18 years 2010 to old above September 19, - transient home- 2013 financially hard up, (Community no relative in based) Manila BAHAY TULUYAN, INC. -

The La Solidaridad and Philippine Journalism in Spain (1889-1895)

44 “Our Little Newspaper”… “OUR LITTLE NEWSPAPER” THE LA SOLIDARIDAD AND PHILIPPINE JOURNALISM IN SPAIN (1889-1895) Jose Victor Z. Torres, PhD De La Salle University-Manila [email protected] “Nuestros periodiquito” or “Our little newspaper” Historian, archivist, and writer Manuel Artigas y was how Marcelo del Pilar described the periodical Cuerva had written works on Philippine journalism, that would serve as the organ of the Philippine especially during the celebration of the tercentenary reform movement in Spain. For the next seven years, of printing in 1911. A meticulous researcher, Artigas the La Solidaridad became the respected Philippine newspaper in the peninsula that voiced out the viewed and made notes on the pre-war newspaper reformists’ demands and showed their attempt to collection in the government archives and the open the eyes of the Spaniards to what was National Library. One of the bibliographical entries happening to the colony in the Philippines. he wrote was that of the La Solidaridad, which he included in his work “El Centenario de la Imprenta”, But, despite its place in our history, the story of a series of articles in the American period magazine the La Solidaridad has not entirely been told. Madalas Renacimiento Filipino which ran from 1911-1913. pag-usapan pero hindi alam ang kasaysayan. We do not know much of the La Solidaridad’s beginnings, its Here he cited a published autobiography by reformist struggle to survive as a publication, and its sad turned revolutionary supporter, Timoteo Paez as his ending. To add to the lacunae of information, there source. -

Nationalism, Citizenship and the Politics of Filipino Migrant Labor ROBYN M

Citizenship Studies, Vol. 6, No. 3, 2002 Migrant Heroes: Nationalism, Citizenship and the Politics of Filipino Migrant Labor ROBYN M. RODRIGUEZ The Philippine state has popularized the idea of Filipino migrants as the country’s ‘new national heroes’, critically transforming notions of Filipino citizenship and citizenship struggles. As ‘new national heroes’, migrant workers are extended particular kinds of economic and welfare rights while they are abroad even as they are obligated to perform particular kinds of duties to their home state. The author suggests that this transnationalize d citizenship, and the obligations attached to it, becomes a mode by which the Philippine state ultimately disciplines Filipino migrant labor as exible labor. However, as citizenship is extended to Filipinos beyond the borders of the Philippines, the globalizatio n of citizenship rights has enabled migrants to make various kinds of claims on the Philippine state. Indeed, these new transnationa l political strug- gles have given rise not only to migrants’ demands for rights, but to alternative nationalisms and novel notions of citizenship that challenge the Philippine state’s role in the export and commodi cation of migrant workers. Introduction In 1995, Flor Contemplacion, a Singapore-based Filipina domestic worker, was hanged by the Singaporean government for allegedly killing another Filipina domestic worker and the child in her charge. When news about her imminent death reached the Philippines, Filipinos, throughout the nation and around the globe, went to the streets demanding that the Philippine government intervene to prevent Contemplacion’s execution. Fearing Philippine– Singapore diplomatic relations would be threatened, then-Philippine President Fidel Ramos was reluctant to intercede despite evidence that may have proved her innocence. -

ANTH 317 Final Paper

Castilian Friars, Colonialism and Language Planning: How the Philippines Acquired a Non- Spanish National Language The topic of the process behind the establishment of a national language, who chooses it, when and why, came to me in an unexpected way. The UBC Philippine Studies Series hosted an art exhibit in Fall 2011 that was entitled MAHAL. This exhibit consisted of artworks by Filipino/a students that related to the Filipino migratory experience(s). I was particularly fascinated by the piece entitled Ancients by Chaya Go (Fig 1). This piece consisted of an image, a map of the Philippines, superimposed with Aztec and Mayan imprints and a pre-colonial Filipina priestess. Below it was a poem, written in Spanish. Chaya explained that “by writing about an imagined ‘home’ (the Philippines) in a language that is not ours anymore, I am playing with the idea of who is Filipino and who belongs to the country” (personal communication, November 29 2011). What I learned from Chaya Go and Edsel Ya Chua that evening at MAHAL, that was confirmed in the research I uncovered, was that in spite of being colonized for over three hundred and fifty years the Philippines now has a national language, Filipino, that is based on the Tagalog language which originated in and around Manila, the capital city of the Philippines (Himmelmann 2005:350). What fascinated me was that every Spanish colony that I could think of, particularly in Latin and South America, adopted Spanish as their national language even after they gained independence from Spain. This Spanish certainly differed from the Spanish in neighboring countries and regions, as each form of Spanish was locally influenced by the traditional languages that had existed before colonization, but its root was Spanish and it identified itself as Spanish. -

V49 No 1 2013

1 Journal of Critical Perspectives on Asia Vinod Raina (1950–2013) Eduardo C. TADEM and Katrina S. NAVALLO Introduction Eduardo C. TADEM and Janus Isaac V. NOLASCO ARTICLES From Cádiz to La Liga: The Spanish Context of Rizal’s Political Thought George ASENIERO Rural China: From Modernization to Reconstruction Tsui SIT and Tak Hing WONG A Preliminary Study of Ceiling Murals from Five Southeastern Cebu Churches Reuben Ramas CAÑETE Bayan Nila: Pilipino Culture Nights and Student Performance at Home in Southern California Neal MATHERNE COMMENTARIES Identity Politics in the Developmentalist States of East Asia: The Role of Diaspora Communities in the Growth of Civil Societies Kinhide MUSHAKOJI La Liga in Rizal Scholarship George ASENIERO Influence of Political Parties on the Judicial Process in Nepal Md. Nurul MOMEN REVIEWS LITERARY WRITINGS Thomas David CHAVES Celine SOCRATES Volume V4olume9 Number 49:1 (2013) 1 2013 2 ASIAN STUDIES is an open-access, peer-reviewed academic journal published since 1963 by the Asian Center, University of the Philippines Diliman. EDITORIAL BOARD* • Eduardo C. Tadem (Editor in Chief), Asian Studies • Michiyo Yoneno-Reyes (Book Review editor), Asian Studies • Eduardo T. Gonzalez, Asian and Philippine Studies • Ricardo T. Jose, History • Joseph Anthony Lim, Economics • Antoinette R. Raquiza, Asian Studies • Teresa Encarnacion Tadem, Political Science • Lily Rose Tope, English and Comparative Literature *The members of the Editorial Board are all from the University of the Philippines Diliman EDITORIAL STAFF • Janus Isaac V. Nolasco, Managing Editor • Katrina S. Navallo, Editorial Associate • Ariel G. Manuel, Layout Artist EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD • Patricio N. Abinales, University of Hawaii at Manoa • Andrew Charles Bernard Aeria, University of Malaysia Sarawak • Benedict Anderson, Cornell University • Melani Budianta, University of Indonesia • Urvashi Butalia, Zubaan Books (An imprint of Kali for Women) • Vedi Renandi Hadiz, Murdoch University • Caroline S. -

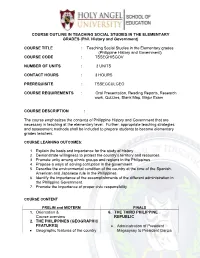

COURSE OUTLINE in TEACHING SOCIAL STUDIES in the ELEMENTARY GRADES (Phil

COURSE OUTLINE IN TEACHING SOCIAL STUDIES IN THE ELEMENTARY GRADES (Phil. History and Government) COURSE TITLE : Teaching Social Studies in the Elementary grades (Philippine History and Government) COURSE CODE : TSSEGHISGOV NUMBER OF UNITS : 3 UNITS CONTACT HOURS : 3 HOURS PREREQUISITE : TSSEGCULGEO COURSE REQUIREMENTS : Oral Presentation, Reading Reports, Research work, Quizzes, Blank Map, Major Exam COURSE DESCRIPTION : The course emphasizes the contents of Philippine History and Government that are necessary in teaching at the elementary level. Further, appropriate teaching strategies and assessment methods shall be included to prepare students to become elementary grades teachers. COURSE LEARNING OUTCOMES: 1. Explain the basis and importance for the study of history. 2. Demonstrate willingness to protect the country’s territory and resources. 3. Promote unity among ethnic groups and regions in the Philippines 4. Propose a ways of solving corruption in the government 5. Describe the environmental condition of the country at the time of the Spanish, American and Japanese rule in the Philippines. 6. Identify the importance of the accomplishments of the different administration in the Philippine Government. 7. Promote the importance of proper civic responsibility COURSE CONTENT PRELIM and MIDTERM FINALS 1. Orientation & 6. THE THIRD PHILIPPINE Course overview REPUBLIC 2. THE PHILIPPINES (GEOGRAPHIC FEATURES) Administration of President Geographic features of the country Magsaysay to President Garcia Natural resources Regions of the Philippine Administration of President Profile of the Filipinos as a People Macapagal and President Marcos 3. PRE SPANISH PERIOD 7. THE FOURTH REPUBLIC The first Filipinos (MARTIAL LAW PERIOD) Ancestors’ cultures and way of life The Declaration of Martial Law The arrival and spread of Islam The end of Military Rule 4.