Colonial Contractions: the Making of the Modern Philippines, 1565–1946

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reflections on Agoncilloʼs the Revolt of the Masses and the Politics of History

Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 49, No. 3, December 2011 Reflections on Agoncilloʼs The Revolt of the Masses and the Politics of History Reynaldo C. ILETO* Abstract Teodoro Agoncilloʼs classic work on Andres Bonifacio and the Katipunan revolt of 1896 is framed by the tumultuous events of the 1940s such as the Japanese occupation, nominal independence in 1943, Liberation, independence from the United States, and the onset of the Cold War. Was independence in 1946 really a culmination of the revolution of 1896? Was the revolution spearheaded by the Communist-led Huk movement legitimate? Agoncilloʼs book was written in 1947 in order to hook the present onto the past. The 1890s themes of exploitation and betrayal by the propertied class, the rise of a plebeian leader, and the revolt of the masses against Spain, are implicitly being played out in the late 1940s. The politics of hooking the present onto past events and heroic figures led to the prize-winning manuscriptʼs suppression from 1948 to 1955. Finally seeing print in 1956, it provided a novel and timely reading of Bonifacio at a time when Rizalʼs legacy was being debated in the Senate and as the Church hierarchy, priests, intellectuals, students, and even general public were getting caught up in heated controversies over national heroes. The circumstances of how Agoncilloʼs work came to the attention of the author in the 1960s are also discussed. Keywords: Philippine Revolution, Andres Bonifacio, Katipunan society, Cold War, Japanese occupation, Huk rebellion, Teodoro Agoncillo, Oliver Wolters Teodoro Agoncilloʼs The Revolt of the Masses: The Story of Bonifacio and the Katipunan is one of the most influential books on Philippine history. -

Military History Anniversaries 01 Thru 14 Feb

Military History Anniversaries 01 thru 14 Feb Events in History over the next 14 day period that had U.S. military involvement or impacted in some way on U.S military operations or American interests Feb 01 1781 – American Revolutionary War: Davidson College Namesake Killed at Cowan’s Ford » American Brigadier General William Lee Davidson dies in combat attempting to prevent General Charles Cornwallis’ army from crossing the Catawba River in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina. Davidson’s North Carolina militia, numbering between 600 and 800 men, set up camp on the far side of the river, hoping to thwart or at least slow Cornwallis’ crossing. The Patriots stayed back from the banks of the river in order to prevent Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tartleton’s forces from fording the river at a different point and surprising the Patriots with a rear attack. At 1 a.m., Cornwallis began to move his troops toward the ford; by daybreak, they were crossing in a double-pronged formation–one prong for horses, the other for wagons. The noise of the rough crossing, during which the horses were forced to plunge in over their heads in the storm-swollen stream, woke the sleeping Patriot guard. The Patriots fired upon the Britons as they crossed and received heavy fire in return. Almost immediately upon his arrival at the river bank, General Davidson took a rifle ball to the heart and fell from his horse; his soaked corpse was found late that evening. Although Cornwallis’ troops took heavy casualties, the combat did little to slow their progress north toward Virginia. -

Un Mundo Ilustrado

UN MUNDO ILUSTRADO José Rizal formó parte del mundo ilustrado que floreció en Filipinas a fines del siglo XIX. En él se incluía una élite de personas educadas en universidades filipinas, que frecuentemente completaban su formación en instituciones europeas. Este grupo de ilustrados, identificados más por su grado de educación que por un único nivel socioeconómico, fue esencial en la formación de una conciencia nacional filipina. Ilustrados fueron pintores como Juan Luna y Novicio o Félix Resurrección Hidalgo, formados en las notables escuelas de dibujo existentes en Manila y especializados en Academias de Bellas Artes europeas. La destreza de sus pinceles les llevó a ganar importantes certámenes internacionales. Los ilustrados se interesaron también por el estudio de la Lengua, bien fuera a través de investigaciones sobre los antiguos alfabetos filipinos o los muchos dialectos del archipiélago, bien a través del aprendizaje de los idiomas modernos. Tenían tras ellos, además, una larga tradición de elaboración de gramáticas, iniciada por los religiosos españoles en 1610, cuando Fr. Joseph publicó en Filipinas la primera gramática tagala. Posteriormente, otros autores estudiaron el visayo, el pampago, el ilocano… Rizal insertó sus estudios gramaticales, que abarcaron desde el tagalo a los jeroglíficos egipcios, pasando por más de diez lenguas, en esa tradición. Algo parecido ocurrió con el conocimiento de la Historia. Desde el siglo XVI se escribieron importantes estudios históricos sobre el archipiélago – Chirino, 1604; Colín, 1663; San Agustín, 1698; Aduarte, 1693… – Rizal prosiguió esa dinámica, anotando los Sucesos de Filipinas escritos por Antonio de Morga en 1609, en lo que se ha considerado como la primera historia de las islas escrita por un filipino. -

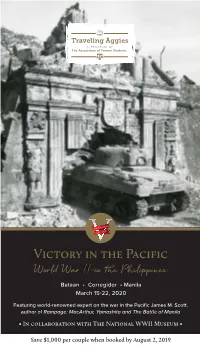

2020 Philippines A&M V2.Indd

y th Year of Victor Victory in the Pacific M A Y 19 4 World War II in the Philippines 5 Bataan • Corregidor • Manila March 15-22, 2020 Featuring world-renowned expert on the war in the Pacific James M. Scott, author of Rampage: MacArthur, Yamashita and The Battle of Manila • In collaboration with The National WWII Museum • Save $1,000 per couple when booked by August 2, 2019 1946 Corregidor Muster. Photo by James T. Danklefs ‘43 Howdy, Ags! On December 7, 1941, the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked the US Pacific Fleet The Traveling Aggies are pleased to partner with The National WWII Museum on at Pearl Harbor. Just a few hours later, the Philippines faced the same fury Victory in the Pacific: World War II in the Philippines. This fascinating journey will as the Japanese Army Air Force began bombing Clark Field, located north of begin in the lush province of Bataan, where tour participants will walk the first Manila. Five months later, the Japanese forced the Americans in the Philippines kilometer of the Death March and visit the remains of the prisoner of war camp at to surrender, but not before General MacArthur could slip away to Australia, Cabanatuan. On the island of Corregidor, 27 miles out in Manila Bay, guests will famously vowing, “I shall return.” see the blasted, skeletal remains of the mile-long barracks, theater, hospital, and officers’ quarters, as well as the monument built and dedicated by The Association After the fall of the Philippines, 70,000 captured American and Filipino soldiers near Malinta Tunnel in 2015, flying the Texas A&M flag and representing the were sent on the infamous “Bataan Death March,” a 65-mile forced march into sacrifice, bravery and Aggie Spirit of the men who Mustered there. -

"Patria É Intereses": Reflections on the Origins and Changing Meanings of Ilustrado

3DWULD«LQWHUHVHV5HIOHFWLRQVRQWKH2ULJLQVDQG &KDQJLQJ0HDQLQJVRI,OXVWUDGR Caroline Sy Hau Philippine Studies, Volume 59, Number 1, March 2011, pp. 3-54 (Article) Published by Ateneo de Manila University DOI: 10.1353/phs.2011.0005 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/phs/summary/v059/59.1.hau.html Access provided by University of Warwick (5 Oct 2014 14:43 GMT) CAROLINE SY Hau “Patria é intereses” 1 Reflections on the Origins and Changing Meanings of Ilustrado Miguel Syjuco’s acclaimed novel Ilustrado (2010) was written not just for an international readership, but also for a Filipino audience. Through an analysis of the historical origins and changing meanings of “ilustrado” in Philippine literary and nationalist discourse, this article looks at the politics of reading and writing that have shaped international and domestic reception of the novel. While the novel seeks to resignify the hitherto class- bound concept of “ilustrado” to include Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs), historical and contemporary usages of the term present conceptual and practical difficulties and challenges that require a new intellectual paradigm for understanding Philippine society. Keywords: rizal • novel • ofw • ilustrado • nationalism PHILIPPINE STUDIES 59, NO. 1 (2011) 3–54 © Ateneo de Manila University iguel Syjuco’s Ilustrado (2010) is arguably the first contemporary novel by a Filipino to have a global presence and impact (fig. 1). Published in America by Farrar, Straus and Giroux and in Great Britain by Picador, the novel has garnered rave reviews across Mthe Atlantic and received press coverage in the Commonwealth nations of Australia and Canada (where Syjuco is currently based). -

World War Ii in the Philippines

WORLD WAR II IN THE PHILIPPINES The Legacy of Two Nations©2016 Copyright 2016 by C. Gaerlan, Bataan Legacy Historical Society. All Rights Reserved. World War II in the Philippines The Legacy of Two Nations©2016 By Bataan Legacy Historical Society Several hours after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the Philippines, a colony of the United States from 1898 to 1946, was attacked by the Empire of Japan. During the next four years, thou- sands of Filipino and American soldiers died. The entire Philippine nation was ravaged and its capital Ma- nila, once called the Pearl of the Orient, became the second most devastated city during World War II after Warsaw, Poland. Approximately one million civilians perished. Despite so much sacrifice and devastation, on February 20, 1946, just five months after the war ended, the First Supplemental Surplus Appropriation Rescission Act was passed by U.S. Congress which deemed the service of the Filipino soldiers as inactive, making them ineligible for benefits under the G.I. Bill of Rights. To this day, these rights have not been fully -restored and a majority have died without seeing justice. But on July 14, 2016, this mostly forgotten part of U.S. history was brought back to life when the California State Board of Education approved the inclusion of World War II in the Philippines in the revised history curriculum framework for the state. This seminal part of WWII history is now included in the Grade 11 U.S. history (Chapter 16) curriculum framework. The approval is the culmination of many years of hard work from the Filipino community with the support of different organizations across the country. -

War Crimes in the Philippines During WWII Cecilia Gaerlan

War Crimes in the Philippines during WWII Cecilia Gaerlan When one talks about war crimes in the Pacific, the Rape of Nanking instantly comes to mind.Although Japan signed the 1929 Geneva Convention on the Treatment of Prisoners of War, it did not ratify it, partly due to the political turmoil going on in Japan during that time period.1 The massacre of prisoners-of-war and civilians took place all over countries occupied by the Imperial Japanese Army long before the outbreak of WWII using the same methodology of terror and bestiality. The war crimes during WWII in the Philippines described in this paper include those that occurred during the administration of General Masaharu Homma (December 22, 1941, to August 1942) and General Tomoyuki Yamashita (October 8, 1944, to September 3, 1945). Both commanders were executed in the Philippines in 1946. Origins of Methodology After the inauguration of the state of Manchukuo (Manchuria) on March 9, 1932, steps were made to counter the resistance by the Chinese Volunteer Armies that were active in areas around Mukden, Haisheng, and Yingkow.2 After fighting broke in Mukden on August 8, 1932, Imperial Japanese Army Vice Minister of War General Kumiaki Koiso (later convicted as a war criminal) was appointed Chief of Staff of the Kwantung Army (previously Chief of Military Affairs Bureau from January 8, 1930, to February 29, 1932).3 Shortly thereafter, General Koiso issued a directive on the treatment of Chinese troops as well as inhabitants of cities and towns in retaliation for actual or supposed aid rendered to Chinese troops.4 This directive came under the plan for the economic “Co-existence and co-prosperity” of Japan and Manchukuo.5 The two countries would form one economic bloc. -

Angeline Quinto Sacrifice Lovelife for Sake of Family

OCTOBER 2016 CONFIDENTIAL Obama warns China Obama and Duterte meet VIENTIANE—US President Barack that threatens regional security. strategically vital waters despite a July Obama warned Beijing Thursday it could The dispute has raised fears of not ignore a tribunal’s ruling rejecting its military confrontation between the OBAMA sweeping claims to the South China Sea, world’s superpowers, with China driving tensions higher in a territorial row determined to cement control of the continued on page 7 Dr. Solon Guzman pose with the winner of Miss FBANA 2016 Miss Winnipeg, “Princess Wy”. Dolorosa President Philip Beloso cooks his famous chicharon at the picnic. UMAC and Forex staff pose with Bamboo and Abra. ANGELINE The singing group Charms perfrom at the PIDC Mabuhay festival. QUINTO Family Come First Miss Philippines 2015 Conida Marie Halley emcees the Mabuhay Festival. Jasmnine Flores, Miss Teen Philippines Canada 2016 Chiara Silo and PCCF 1st runner-up Shnaia RG perform at the Tamil Festival. THE Beautiful Girls MMK Bicol Canada VOICE FV Foods’ owner Mel Galeon poses with Charo Santos Con- cio, Chief Content Officer of Bicol Canada President and Action Honda Manager Rafael ABS at the recent Maalaala Mo Nebres (5TH FROM RIGHT) poses with participants at the Samantha Gavin and melissa Saldua Ventocilla walks the JDL’s Josie de Leon perfroms at Kaya (MMK) forum in Toronto. Bicol Canada Community Association Summer Picnic at Earl ramp at the PIDC Mabuhay Fashion Show. the Mabuhay Festival. bales Park. OCTOBER 2016 OCTOBER 2016 L. M. Confidential -

Chua / Hamon at Tugon / Bersyong 13 Abril 2013 1 HAMON at TUGON Conquista at Reaksyon Ng Bayan Tungo Sa Pambansang Himagsikan* (

Chua / Hamon at Tugon / Bersyong 13 Abril 2013 1 HAMON AT TUGON Conquista at Reaksyon ng Bayan Tungo sa Pambansang Himagsikan * (1571-1913) Michael Charleston “Xiao” B. Chua Pamantasang De La Salle Maynila Maikling Paglalarawan ng Paksa ng Modyul-Gabay: Nakaugalian nang ilahad ang kasaysayan ng kolonyalismo sa pananaw ng mga opisyal na dokumento ng mga dayuhan at mga kolonyalistang sanaysay na nagpatibay ng kolonyal na mentalidad ng Pilipino na ang Kanluran ay laging daluyan ng ginhawa. Liban pa sa nawalan na ng saysay ang nakaraang ito sa maraming Pilipino dahil hindi nito talaga nasalamin ang kanilang kamalayan. Ang Nasyunalistang Kasaysayan ni Agoncillo, na lalong pinaunlad at pinagpapatuloy ng Pantayong Pananaw, ang nagbukas ng daan na lalong maintindihan ang kasaysayan sa pananaw ng mga Pilipino sa nakalipas na mga taon. Ayon kay Zeus A. Salazar at sa iba pang tagapagtaguyod ng Pantayog Pananaw, ang Kasaysayan ay “salaysay na may saysay para sa sinasalaysayang grupo ng tao.” Sa paglalahad ng kwento mula sa pananaw ng mga lider tungo sa pananaw ng mga namumuhay ng kalinangan—ang mga mamamayan, nais ng module na ito na ipakita ang pag-unlad ng kapuluan mula sa iba’t ibang bayan tungo sa pagiging isang bansa. Ang karanasan ng Conquista at pakikibaka ang nagbuo sa bayan tungo sa kamalayang pambansa, na ang magiging katuparan ay ang Himagsikang Pilipino ng 1896. Sa kasamaang palad, dahil sa Dambuhalang Pagkakahating Pangkalinangan, nagkaroon din ng tunggalian sa loob ng bansa, kaya naman hindi pa rin natatapos ang gawain ng pagbubuo nito tungo sa tunay na kaginhawaan ng mga Pilipino. Mga Layunin: 1. -

Kathryn Bernardo Winning Over Her Self-Doubt Bernardo’S Story Is Not Just All About Teleserye Roles

ittle anila L.M.ConfidentialMARCH - APRIL 2013 Stolen Art on the Rise in the Philippines MANILA, Philippines - Art dealers and buyers beware: Criminal syndicates have developed a taste for fine art and, moving like a pack of wolves, they know exactly what to get their filthy paws on and how to pass the blame on to unsuspecting gallery staffers or art collectors. Many artists, art galleries, and collectors who have fallen victim to heists can attest to this, but opt to keep silent. But do their silence merely perpetuate the growing art thievery in the industry? Because he could no longer agonize silently after a handful of his sought-after creations have been lost KATHRYN to recent robberies and break-ins, sculptor Ramon Orlina gave the Inquirer pertinent information on what appears to be a new art theft modus operandi that he and some of the galleries carrying his works Bernardo have come across. Perhaps the latest and most brazen incident was a failed attempt to ransack the Orlina atelier Winning Over in Sampaloc early in February! ORLINA’S “Protector,” Self-Doubt stolen from Alabang design space Creating alibis Two men claiming to be artists paid a visit to the sculptor’s Manila workshop and studio while the artist’s workers Student kills self over Tuition were on break; they told the staff they were in search of sculptures kept in storage. UP president: Reforms under way after coed’s tragedy The pair informed Orlina’s secretary that they wanted to purchase a few pieces immediately and MANILA, Philippines - In death, and its student support system In a statement addressed to the asked to be brought to where smaller works were Kristel Pilar Mariz Tejada has under scrutiny, UP president UP community and alumni, Pascual housed. -

Philippine Independence Day Issue

P Philippine Independence Day Issue Editor’s Notes: ………………………… “Happy Independence Day, Philippines!” ……………………. Eddie Zamora Featured Items: 1. Philippine Independence Day, A Brief History ……………………………………………………………………….. The Editor 2. I Am Proud To Be A Filipino ……………………………………………………………………….. by Nelson Lagos Ornopia, Sr. 3. Presidents Of The Philippines ……………………………………………………………..………………………………. Group Effort 4. The Philippine Flag and Its Symbols ……………………………………………………………………………………. The Internet 5. The Philippine National Anthem …………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. SULADS Corner: …………………………..………………… “Sulads Is Like A Rose” ………………… by Crisophel Abayan. NEMM Patch of Weeds: …………………………………………………………………………….……………………………..………….. Jesse Colegado LIFE of a Missionary: ………………… “President of SDA Church Visits ‘Land Eternal’”………..………. Romulo M. Halasan CLOSING: Announcements |From The Mail Bag| Prayer Requests | Acknowledgements Meet The Editors |Closing Thoughts | Miscellaneous Happy Independence Day, Philippines! very June 12 the Philippines celebrates its Independence Day. Having lived in America some 30 E years now I am familiar with how people celebrate Independence here—they have parades, barbecues and in the evening fireworks. When we left the Philippines years ago fireworks were banned in the country. I don’t know how it is today. It would be wonderful if Filipinos celebrated Independence Day similar to or better than the usual parades, picnics, barbecues and some fireworks. When I was a kid growing up, Independence Day was observed on July 4th, the day when the United States granted the country independence from American rule. The American flag was finally lowered from government building flagpoles and the Philippine flag was hoisted in its stead. From that day until one day in 1962 the country celebrated Independence Day on the same day the United States celebrated its own Independence Day. But on May 12, 1962 then President Diosdado Macapagal issued Presidential Proclamation No. -

Notices of the Pagan Igorots in 1789 - Part Two

Notices of the Pagan Igorots in 1789 - Part Two By Francisco A ntolin, 0 . P. Translated by W illiam Henry Scott Translator’s Note Fray Francisco Antolin was a Dominican missionary in Dupax and Aritao,Nueva Vizcaya,in the Philippines,between the years 1769 and 1789,who was greatly interested in the pagan tribes generally called “Igorots” in the nearby mountains of the Cordillera Central of northern Luzon. His unpublished 1789 manuscript,Noticias de los infieles igor- rotes en lo interior de la Isla de M anila was an attempt to bring to gether all information then available about these peoples,from published books and pamphlets, archival sources, and personal diaries, corre spondence, interviews and inquiries. An English translation of Part One was published in this journal,V o l.29,pp. 177-253,as “Notices of the pagan Igorots in 1789,” together with a translator’s introduction and a note on the translation. Part Two is presented herewith. Part Two is basically a collection of source materials arranged in chronological order, to which Esther Antolin added comments and discussion where he thought it necessary,and an appendix of citations and discourses (illustraciones) on controversial interpretations. With the exception of some of the Royal Orders (cedulas reales) ,these docu ments are presented in extract or paraphrase rather than as verbatim quotations for the purpose of saving space,removing material of no direct interest,or of suppressing what Father Antolin,as a child of the 18th-century Enlightenment, evidently considered excessive sanctity. Occasionally it is impossible to tell where the quotation ends and Father Antolin,s own comments begin without recourse to the original,which recourse has been made throughout the present translation except in the case of works on the history of mining in Latin America which were not locally available.