Williamite Propaganda in the Anglo-Dutch Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

July at the Museum!

July at the Museum! Battle of Aughrim, John Mulvaney. The Battle of the Boyne, July 1st 1690. On 1 July 1690, the Battle of the Boyne was fought between King James II's Jacobite army, and the Williamite Army under William of Orange. Despite only being a minor military victory in favour of the Williamites, it has a major symbolic significance. The Battle's annual commemorations by The Orange Order, a masonic-style fraternity dedicated to the protection of the Protestant Ascendancy, remain a topic of great controversy. This is especially true in areas of Northern Ireland where sectarian tensions remain rife. No year in Irish history is better known than 1690. No Irish battle is more famous than William III's victory over James II at the River Boyne, a few miles west of Drogheda. James, a Roman Catholic, had lost the throne of England in the bloodless "Glorious Revolution" of 1688. William was Prince of Orange, a Dutch-speaking Protestant married to James's daughter Mary, and became king at the request of parliament. James sought refuge with his old ally, Louis XIV of France, who saw an opportunity to strike at William through Ireland. He provided French officers and arms for James, who landed at Kinsale in March 1689. The lord deputy, the Earl of Tyrconnell was a Catholic loyal to James, and his Irish army controlled most of the island. James quickly summoned a parliament, largely Catholic, which proceeded to repeal the legislation under which Protestant settlers had acquired land. During the rule of Tyrconnell, the first Catholic viceroy since the Reformation, Protestants had seen their influence eroded in the army, in the courts and in civil government. -

Researching Huguenot Settlers in Ireland

BYU Family Historian Volume 6 Article 9 9-1-2007 Researching Huguenot Settlers in Ireland Vivien Costello Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byufamilyhistorian Recommended Citation The BYU Family Historian, Vol. 6 (Fall 2007) p. 83-163 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Family Historian by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. RESEARCHING HUGUENOT SETTLERS IN IRELAND1 VIVIEN COSTELLO PREAMBLE This study is a genealogical research guide to French Protestant refugee settlers in Ireland, c. 1660–1760. It reassesses Irish Huguenot settlements in the light of new findings and provides a background historical framework. A comprehensive select bibliography is included. While there is no formal listing of manuscript sources, many key documents are cited in the footnotes. This work covers only French Huguenots; other Protestant Stranger immigrant groups, such as German Palatines and the Swiss watchmakers of New Geneva, are not featured. INTRODUCTION Protestantism in France2 In mainland Europe during the early sixteenth century, theologians such as Martin Luther and John Calvin called for an end to the many forms of corruption that had developed within the Roman Catholic Church. When their demands were ignored, they and their followers ceased to accept the authority of the Pope and set up independent Protestant churches instead. Bitter religious strife throughout much of Europe ensued. In France, a Catholic-versus-Protestant civil war was waged intermittently throughout the second half of the sixteenth century, followed by ever-increasing curbs on Protestant civil and religious liberties.3 The majority of French Protestants, nicknamed Huguenots,4 were followers of Calvin. -

Orange Alba: the Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland Since 1798

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2010 Orange Alba: The Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland since 1798 Ronnie Michael Booker Jr. University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Booker, Ronnie Michael Jr., "Orange Alba: The Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland since 1798. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2010. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/777 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Ronnie Michael Booker Jr. entitled "Orange Alba: The Civil Religion of Loyalism in the Southwestern Lowlands of Scotland since 1798." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in History. John Bohstedt, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Vejas Liulevicius, Lynn Sacco, Daniel Magilow Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by R. -

Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi………………………………………

CBÜ SOSYAL BİLİMLER DERGİSİ Cilt:13, Sayı:3, Eylül 2015 Geliş Tarihi: 11.06.2015 Doi Number: 10.18026/cbusos.32235 Kabul Tarihi: 25.06.2015 RECONSTRUCTING THE HERO: REPRESENTATION OF LOYALTY IN LATE ANGLO-SAXON LITERATURE Şafak NEDİCEYUVA1 ABSTRACT Danish attacks on the British Isles in the 9th century had considerable political consequences for the seven Anglo-Saxon kingdoms reigning independently at the time. ‘The Great Heathen Army’, as the Anglo-Saxon called it, began a series of invasions in Britain and their advance was unstoppable until all Anglo-Saxon kingdoms but Wessex were conquered. Emerging as the rulers of only surviving Anglo-Saxon kingdom, Alfred and the subsequent monarchs of Wessex began a slow process of unifying the subjugated Anglo-Saxons under their banner and they desired to be acknowledged as the kings of England, rather than Wessex. By adapting traditional heroic values to contemporary political needs, literary works of this period similarly attempt to channel former tribal loyalties towards the monarch and propagandize absolute devotion to the survival and construction of ‘England’. This article discusses the ideological role literature played in late Anglo-Saxon era during the formation of England. Keywords: Anglo-Saxon, Viking, hero, heroic code, military organization. KAHRAMANIN YENİDEN KURGULANIŞI: GEÇ DÖNEM ANGLOSAKSON EDEBİYATI’NDA SADAKATİN TEMSİLİ ÖZ Dokuzuncu yüzyılda Britanya Adaları’na yapılan Viking saldırıları burada hüküm süren yedi bağımsız Anglosakson krallığı için önemli siyasi sonuçlar doğurmuştur. Anglosaksonların ‘Büyük Dinsiz Ordu’ adını verdikleri ordu Britanya’yı istila etmeye başlamış ve Wessex Krallığı dışında tüm diğer krallıklar yıkılana kadar durdurulamamıştır. Alfred ve ondan sonra tahta çıkan Wessex kralları ayakta kalan tek Anglosakson krallığının hükümdarları olarak Viking buyruğu altındaki Anglosaksonları kendi bayrakları altında bir araya getirmeyi ve Wessex değil İngiltere krallığı olarak tanınmayı arzulamışlardır. -

English Legal History Mon., 13 Sep

Outline--English Legal History Mon., 13 Sep. Page 1 ANGLO-SAXON CONSTITUTIONAL HISTORY IN BRIEF SOURCES 1. Narrative history: Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People (Bede died 735); the Anglo- Saxon Chronicle (late 9th to mid-12th centuries); Gildas, On the Downfall and Conquest of Britain (1st half of 6th century). 2. The so-called “law codes,” beginning with Æthelberht (c. 600) and going right up through Cnut (d. 1035). 3. Language and literature: Beowulf, lyric poetry, translations of pieces of the Bible, sermons, saints’ lives, medical treatises, riddles, prayers 4. Place-names; geographical features 5. Coins 6. Art and archaeology 7. Charters BASIC CHRONOLOGY 1. The main chronological periods (Mats. p. II–1): ?450–600 — The invasions to Æthelberht of Kent Outline--English Legal History Mon., 13 Sep. Page 2 600–835 — (A healthy chunk of time here; the same amount of time that the United States has been in existence.) The period of the Heptarchy—overlordships moving from Northumbria to Mercia to Wessex. 835–924 — The Danish Invasions. 924–1066 — The kingdom of England ending with the Norman Conquest. 2. The period of the invasions (Bede on the origins of the English settlers) (Mats. p. II–1), 450–600 They came from three very powerful nations of the Germans, namely the Saxons, the Angles and the Jutes. From the stock of the Jutes are the people of Kent and the people of Wight, that is, the race which holds the Isle of Wight, and that which in the province of the West Saxons is to this day called the nation of the Jutes, situated opposite that same Isle of Wight. -

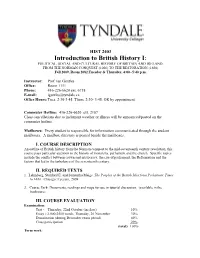

Introduction to British History I

HIST 2403 Introduction to British History I: POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND, FROM THE NORMAN CONQUEST (1066) TO THE RESTORATION (1660) Fall 2009, Room 2082,Tuesday & Thursday, 4:00--5:40 p.m. Instructor: Prof. Ian Gentles Office: Room 1111 Phone: 416-226-6620 ext. 6718 E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Tues. 2:30-3:45, Thurs. 2:30- 3:45, OR by appointment Commuter Hotline: 416-226-6620 ext. 2187 Class cancellations due to inclement weather or illness will be announced/posted on the commuter hotline. Mailboxes: Every student is responsible for information communicated through the student mailboxes. A mailbox directory is posted beside the mailboxes. I. COURSE DESCRIPTION An outline of British history from the Norman conquest to the mid-seventeenth century revolution, this course pays particular attention to the history of monarchy, parliament and the church. Specific topics include the conflict between crown and aristocracy, the rise of parliament, the Reformation and the factors that led to the turbulence of the seventeenth century. II. REQUIRED TEXTS 1. Lehmberg, Stanford E. and Samantha Meigs. The Peoples of the British Isles from Prehistoric Times to 1688 . Chicago: Lyceum, 2009 2. Course Pack: Documents, readings and maps for use in tutorial discussion. (available in the bookstore) III. COURSE EVALUATION Examination : Test - Thursday, 22nd October (in class) 10% Essay - 2,000-2500 words, Thursday, 26 November 30% Examination (during December exam period) 40% Class participation 20% (total) 100% Term work : a. You are expected to attend the tutorials, preparing for them through the lectures and through assigned reading. -

Thevikingblitzkriegad789-1098.Pdf

2 In memory of Jeffrey Martin Whittock (1927–2013), much-loved and respected father and papa. 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A number of people provided valuable advice which assisted in the preparation of this book; without them, of course, carrying any responsibility for the interpretations offered by the book. We are particularly indebted to our agent Robert Dudley who, as always, offered guidance and support, as did Simon Hamlet and Mark Beynon at The History Press. In addition, Bradford-on-Avon library, and the Wiltshire and the Somerset Library services, provided access to resources through the inter-library loans service. For their help and for this service we are very grateful. Through Hannah’s undergraduate BA studies and then MPhil studies in the department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse and Celtic (ASNC) at Cambridge University (2008–12), the invaluable input of many brilliant academics has shaped our understanding of this exciting and complex period of history, and its challenging sources of evidence. The resulting familiarity with Old English, Old Norse and Insular Latin has greatly assisted in critical reflection on the written sources. As always, the support and interest provided by close family and friends cannot be measured but is much appreciated. And they have been patient as meal-time conversations have given way to discussions of the achievements of Alfred and Athelstan, the impact of Eric Bloodaxe and the agendas of the compilers of the 4 Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. 5 CONTENTS Title Dedication Acknowledgements Introduction 1 The Gathering -

The Anglo-Saxons

The Anglo-Saxons “In the case of the king, the resources and tools with which to rule are that he have his land fully manned: he must have praying men, fighting men and working men. You know also that without these tools no king may make his ability known.” King Alfred’s digressions in his translation of Boethius’s “Consolation of Philosophy” This module includes the following topics: ❖ Anglo-Saxon Timeline ❖ The Anglo-Saxons ❖ Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms ❖ Society and Structure ❖ Anglo-Saxon Kings End of Anglo-Saxon ❖ Depiction of an Anglo- Kingdom Saxon King with nobles LEARNING OBJECTIVES KEY WORDS At the end of the module, Anglo- Tithing you should be able to: Hundreds Trace the beginning and Saxon ❖ Normans end of the Anglo-Saxon Jutes Burghs period of England Saxons ❖ Map the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms Angles ❖ Be familiar with the rule Kingdoms and succession of Paganism Anglo-Saxon kings Christianity ❖ Analyse the life and society of the Anglo- Saxons ANGLO-SAXON TIMELINE In 410, after the By 793, Danish By 597, St. Augustine, an sacking of Rome by Viking raiders Italian monk, arrived in Alaric, King of the began attacking Kent and founded a Goths, Roman Lindisfarne, Jarrow, Benedictine monastery at legions departed and Iona. Canterbury and converted from Britannia. the King of Kent to Alfred the Great By 449, three Christianity. defeated the Danes shiploads of at Edington in 878. Saxon warriors In 635, Aidan founded a led by Hengist monastery in and Horsa arrived Lindisfarne, followed by in Kent. the Synod of Whitby in 664. According to legends, King Arthur defeated the Saxons at Mount Badon in 518. -

Family Group Sheet for Cnut the Great

Family Group Sheet for Cnut the Great Husband: Cnut the Great Birth: Bet. 985 AD–995 AD in Denmark Death: 12 Nov 1035 in England (Shaftesbury, Dorset) Burial: Old Minster, Winchester. Bones now in Winchester Cathedral Father: King Sweyn I Forkbeard Mother: Wife: Emma of Normandy Birth: 985 AD Death: 06 Mar 1052 in Winchester, Hampshire Father: Richard I Duke of Normandy Mother: Gunnor de Crepon Children: 1 Name: Gunhilda of Denmark F Birth: 1020 Death: 18 Jul 1038 Spouse: Henry III 2 Name: Knud III Hardeknud M Birth: 1020 in England Death: 08 Jun 1042 in England Burial: Winchester Cathedral, Winchester, England Notes Cnut the Great Cnut the Great From Wikipedia, (Redirected from Canute the Great) Cnut the Great King of all the English, and of Denmark, of the Norwegians, and part of the Swedes King of Denmark Reign1018-1035 PredecessorHarald II SuccessorHarthacnut King of all England Reign1016-1035 PredecessorEdmund Ironside SuccessorHarold Harefoot King of Norway Reign1028-1035 PredecessorOlaf Haraldsson SuccessorMagnus Olafsson SpouseÆlfgifu of Northampton Emma of Normandy Issue Sweyn Knutsson Harold Harefoot Harthacnut Gunhilda of Denmark FatherSweyn Forkbeard MotherSigrid the Haughty also known as Gunnhilda Bornc. 985 - c. 995 Denmark Died12 November 1035 England (Shaftesbury, Dorset) BurialOld Minster, Winchester. Bones now in Winchester Cathedral Cnut the Great, also known as Canute or Knut (Old Norse: Knútr inn ríki[1] (c. 985 or 995 - 12 November 1035) was a Viking king of England and Denmark, Norway, and parts of Sweden, whose successes as a statesman, politically and militarily, prove him to be one of the greatest figures of medieval Europe and yet at the end of the historically foggy Dark Ages, with an era of chivalry and romance on the horizon in feudal Europe and the events of 1066 in England, these were largely 'lost to history'. -

Anglo-Saxons

Anglo-Saxons Plated disc brooch Kent, England Late 6th or early 7th century AD Visit resource for teachers Key Stage 2 Anglo-Saxons Contents Before your visit Background information Resources Gallery information Preliminary activities During your visit Gallery activities: introduction for teachers Gallery activities: briefings for adult helpers Gallery activity: The Franks Casket Gallery activity: Personal adornment Gallery activity: Design and decoration Gallery activity: Anglo-Saxon jobs Gallery activity: Material matters After your visit Follow-up activities Anglo-Saxons Before your visit Anglo-Saxons Before your visit Background information The end of Roman Britain The Roman legions began to be withdrawn from Britain to protect other areas of the empire from invasion by peoples living on the edge of the empire at the end of the fourth century AD. Around AD 407 Constantine III, a claimant for the imperial throne based in Britain, led the troops from Britain to Gaul in an attempt to secure control of the Western Roman Empire. He failed and was killed in Gaul in AD 411. This left the Saxon Shore forts, which had been built by the Romans to protect the coast from attacks by raiding Saxons, virtually empty and the coast of Britain open to attack. In AD 410 there was a devastating raid on the undefended coasts of Britain and Gaul by Saxons raiders. Imperial governance in Britain collapsed and although aspects of Roman Britain continued after AD 410, Britain was no longer part of the Roman empire and saw increased settlement by Germanic people, particularly in the northern and eastern regions of England. -

History of the English Language

History of the English Language John Gavin Marist CLS Spring 2019 4/4/2019 1 Assumptions About The Course • This is a survey of a very large topic – Course will be a mixture of history and language • Concentrate on what is most relevant – We live in USA – We were colonies of Great Britain until 1776 • English is the dominant language in – United Kingdom of England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland – Former Colonies: USA, Canada, Republic of Ireland, Australia, New Zealand and several smaller scattered colonies 4/4/2019 2 Arbitrary English Language Periods - Course Outline - Period Dates Old English 450 CE to 1066 CE Middle English 1066 CE to 1450 CE Early Modern English 1450 CE to 1700 CE Modern English 1700 CE to present Note: • These periods overlap. • There is not a distinct break. • It’s an evolution. 4/4/2019 3 Geography 4/4/2019 4 Poughkeepsie England X 4/4/2019 5 “England”: not to be confused with British Isles, Great Britain or the United Kingdom Kingdom of England • England (927) • add Wales (1342) Kingdom of Great Britain • Kingdom of England plus Kingdom of Scotland (1707) United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (1801) • All of the British Isles United Kingdom of GrB and Northern Ireland (1922) • less4/4/2019 the Republic of Ireland 6 Language in General 4/4/2019 7 What is a Language? A language is an oral system of communication: • Used by the people of a particular region • Consisting of a set of sounds (pronunciation) – Vocabulary, Grammar • Used for speaking and listening Until 1877 there was no method for recording speech and listening to it later. -

The Plantation of Ulster Document Study Pack Staidéar Bunfhoinsí

Donegal County Archives Cartlann Chontae Dhún na nGall The Plantation of Ulster Document Study Pack Staidéar Bunfhoinsí Plandáil Uladh Contents PAGE Ulster before Plantation 2 O’Doherty’s Rebellion and the Irish in Ulster 3 The Plantation of East Ulster 4 The Scheme for Plantation 5 The King’s Commissioners and Surveys 6 The Grantees – 7 • Undertakers 7 • Servitors 7 • Native Irish 7 • The London Companies 8 • Other Grantees 8 Buildings and Towns – The Birth of the Urban Landscape 9 The Natives and the Plantation 10 The Cultural Impact of the Plantation 11 The Plantation in Donegal 11 The Plantation in Londonderry 13 The 1641 Rebellion and the Irish Confederate Wars 14 The Success of the Plantation of Ulster 16 Who’s who: 17 • The Native Irish 17 • King, Council and Commissioners 18 The Protestant Reformation 19 Dealing with Documents 20 Documents and Exercises 21 Glossary 24 Additional Reading and Useful Websites 25 Acknowledgements 25 | 1 | Ulster before Plantation On the 14th of September 1607 a ship left sides and now expected to be rewarded for the Donegal coast bound for Spain. On board their loyalty to the crown. Also living in the were a number of Irish families, the noblemen province were numbers of ex-soldiers and of Ulster, including: Hugh O’Neill, Earl of officials who also expected to be rewarded for Tyrone, Ruairí O’Donnell, Earl of Tír Chonaill, long years of service. Cú Chonnacht Maguire, Lord of Fermanagh and ninety nine members of their extended O’Neill’s and O’Donnell’s lands were immediately families and households.