Open Muroya Thesis.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sasanian Tradition in ʽabbāsid Art: Squinch Fragmentation As The

The Sasanian Tradition in ʽAbbāsid Art: squinch fragmentation as The structural origin of the muqarnas La tradición sasánida en el arte ʿabbāssí: la fragmentación de la trompa de esquina como origen estructural de la decoración de muqarnas A tradição sassânida na arte abássida: a fragmentação do arco de canto como origem estrutural da decoração das Muqarnas Alicia CARRILLO1 Abstract: Islamic architecture presents a three-dimensional decoration system known as muqarnas. An original system created in the Near East between the second/eighth and the fourth/tenth centuries due to the fragmentation of the squinche, but it was in the fourth/eleventh century when it turned into a basic element, not only all along the Islamic territory but also in the Islamic vocabulary. However, the origin and shape of muqarnas has not been thoroughly considered by Historiography. This research tries to prove the importance of Sasanian Art in the aesthetics creation of muqarnas. Keywords: Islamic architecture – Tripartite squinches – Muqarnas –Sasanian – Middle Ages – ʽAbbāsid Caliphate. Resumen: La arquitectura islámica presenta un mecanismo de decoración tridimensional conocido como decoración de muqarnas. Un sistema novedoso creado en el Próximo Oriente entre los siglos II/VIII y IV/X a partir de la fragmentación de la trompa de esquina, y que en el siglo XI se extendió por toda la geografía del Islam para formar parte del vocabulario del arte islámico. A pesar de su importancia y amplio desarrollo, la historiografía no se ha detenido especialmente en el origen formal de la decoración de muqarnas y por ello, este estudio pone de manifiesto la influencia del arte sasánida en su concepción estética durante el Califato ʿabbāssí. -

Late Anglo-Saxon Finds from the Site of St Edmund's Abbey R. Gem, L. Keen

LATE ANGLO-SAXON FINDS FROM THE SITE OF ST EDMUND'S ABBEY by RICHARD GEM, M.A., PH.D., F.S.A. AND LAURENCE KEEN, M.PHIL., F.S.A., F.R.HIST.S. DURING SITE CLEARANCE of the eastern parts of the church of St Edmund's Abbey by the then Ministry of Works, followingtheir acceptance of the site into guardianship in 1955, two groups of important Anglo-Saxon material were found, but have remained unpublished until now. These comprise a series of fragments of moulded stone baluster shafts and a number of polychrome relief tiles. These are illustrated' and discussed here; it is concluded that the baluster shafts belong to around the second quarter of the 11th century or shortly thereafter; and that the tiles belong to the same period or, possibly, to the 10th century. HISTORY OF THE BUILDINGS OF ME LATE ANGLO-SAXON ABBEY The Tenth-Centwy Minster Whatever weight may be attached to the tradition that a minster was found at Boedericeswirdein the 7th century by King Sigberct, there can be little doubt that the ecclesiastical establishment there only rose to importance in the 10th century as a direct result of the translation to the royal vill of the relics of King Edmund (ob. 870);2this translation is recorded as having taken place in the reign of King Aethelstan (924 —39).3 Abbo of Fleury, writing in the late 10th century, saysthat the people of the place constructed a 'very large church of wonderful wooden plankwork' (permaxima miro ligneo tabulatu ecclesia) in which the relics were enshrined.' Nothing further is known about this building apart from this one tantalising reference. -

March 27, 2018 RESTORATION of CAPPONI CHAPEL in CHURCH of SANTA FELICITA in FLORENCE, ITALY, COMPLETED THANKS to SUPPORT FROM

Media Contact: For additional information, Libby Mark or Heather Meltzer at Bow Bridge Communications, LLC, New York City; +1 347-460-5566; [email protected]. March 27, 2018 RESTORATION OF CAPPONI CHAPEL IN CHURCH OF SANTA FELICITA IN FLORENCE, ITALY, COMPLETED THANKS TO SUPPORT FROM FRIENDS OF FLORENCE Yearlong project celebrated with the reopening of the Renaissance architectural masterpiece on March 28, 2018: press conference 10:30 am and public event 6:00 pm Washington, DC....Friends of Florence celebrates the completion of a comprehensive restoration of the Capponi Chapel in the 16th-century church Santa Felicita on March 28, 2018. The restoration project, initiated in March 2017, included all the artworks and decorative elements in the Chapel, including Jacopo Pontormo's majestic altarpiece, a large-scale painting depicting the Deposition from the Cross (1525‒28). Enabled by a major donation to Friends of Florence from Kathe and John Dyson of New York, the project was approved by the Soprintendenza Archeologia Belle Arti e Paesaggio di Firenze, Pistoia, e Prato, entrusted to the restorer Daniele Rossi, and monitored by Daniele Rapino, the Pontormo’s Deposition after restoration. Soprintendenza officer responsible for the Santo Spirito neighborhood. The Capponi Chapel was designed by Filippo Brunelleschi for the Barbadori family around 1422. Lodovico di Gino Capponi, a nobleman and wealthy banker, purchased the chapel in 1525 to serve as his family’s mausoleum. In 1526, Capponi commissioned Capponi Chapel, Church of St. Felicita Pontormo to decorate it. Pontormo is considered one of the most before restoration. innovative and original figures of the first half of the 16th century and the Chapel one of his greatest masterpieces. -

Pevsner's Architectural Glossary

Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 1 PEVSNER’S ARCHITECTURAL GLOSSARY Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 2 Nikolaus and Lola Pevsner, Hampton Court, in the gardens by Wren's east front, probably c. Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 3 PEVSNER’S ARCHITECTURAL GLOSSARY Yale University Press New Haven and London Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 4 Temple Street, New Haven Bedford Square, London www.pevsner.co.uk www.lookingatbuildings.org.uk www.yalebooks.co.uk www.yalebooks.com for Published by Yale University Press Copyright © Yale University, Printed by T.J. International, Padstow Set in Monotype Plantin All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections and of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 5 CONTENTS GLOSSARY Glossary pages new extra text:Layout 1 10/9/10 16:22 Page 6 FOREWORD The first volumes of Nikolaus Pevsner’s Buildings of England series appeared in .The intention was to make available, county by county, a comprehensive guide to the notable architecture of every period from prehistory to the present day. Building types, details and other features that would not necessarily be familiar to the general reader were explained in a compact glossary, which in the first editions extended to some terms. -

Virginia Theological Seminary Gothic France: 21-31 May 2021

Virginia Theological Seminary Gothic France: 21-31 May 2021 SAMPLE OF PROGRAM* Day 1: Friday, May 21, 2021 Arrival in Paris on your own Group Welcome Dinner in a restaurant Lodging in a 4 * boutique hotel in the 5th or 6th arrondissement of Paris (Hotel des Saint-Pères or similar) Day 2: Saturday May 22, 2021 Meet your private tour bus and 2 guides at your hotel for a guided day in Paris. Guided visit of the church of St Pierre de Montmartre, one of the oldest extant churches in Paris, and the Sacré Coeur Basilica with its mosaic of Christ in Glory. Lunch on your own in historic Montmartre After lunch, meet your tour bus for a guided visit of the St Denis Basilica to learn about the birth of Gothic architecture Return to the hotel at the end of the day. Dinner on your own Lodging in a 4 * boutique hotel in the 5th or 6th arrondissement of Paris (Hotel des Saint-Pères or similar) Day 3: Sunday, May 23, 2021 Meet your private tour bus and your 2 guides in front of your hotel for a day trip to Chartres. Guided tour of Notre Dame de Chartres Cathedral, a unique example of early gothic architecture, th and its 13 century Labyrinth Group Lunch in a restaurant Free time to explore the town of Chartres Return to Paris with your tour bus at the end of the day Dinner on your own Lodging in a 4 * boutique hotel in the 5th or 6th arrondissement of Paris (Hotel des Saint-Pères or similar) Day 4: Monday, May 24, 2021 Meet your 2 guides at your hotel for a guided day in Paris (transport pass provided) Guided visit of Notre Dame Cathedral (the exterior), an iconic masterpiece of Gothic architecture, ravaged by fire in April 2019. -

A Historical Review and Quantitative Analysis of International Criminal Justice

CHAPTER TWELVE A HISTORICAL REVIEW AND QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS OF INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL JUSTICE Section 1. The Historical Stages of International Criminal Justice ICJ made its way into international practice in several stages. The first period ranges from 1268 until 1815, effectively from the first international criminal pros- ecution of Conradin von Hohenstaufen in Naples through the end of World War I. The second stage begins with the signing of the Treaty of Versailles and ranges from 1919 until 2014, when it is expected that all of the existing direct and mixed model tribunals will have closed, leaving only the International Criminal Court (ICC). The third impending stage will begin in January 2015, when the ICC will be the primary international criminal tribunal. 1.1. The Early Historic Period—Thirteenth to Nineteenth Centuries The first period, which could prosaically be called the early historic period, is characterized by three major events occurring in 1268, 1474, and 1815, respectively. In 1268, the trial of Conradin von Hohenstaufen, a German nobleman, took place in Italy when Conradin was sixteen years of age.1 He was tried and exe- cuted for transgressing the Pope’s dictates by attacking a fellow noble French ruler, wherein he pillaged and killed Italian civilians at Tagliacozzo, near Naples. The killings were deemed to constitute crimes “against the laws of God and Man.” The trial was essentially a political one. In fact, it was a perversion of ICJ and demonstrated how justice could be used for political ends. The crime— assuming it can be called that—was in the nature of a “crime against peace,” as that term came to be called in the Nuremberg Charter’s Article 6(a), later to be called aggression under the UN Charter. -

Gothic Beyond Architecture: Manchester’S Collegiate Church

Gothic beyond Architecture: Manchester’s Collegiate Church My previous posts for Visit Manchester have concentrated exclusively upon buildings. In the medieval period—the time when the Gothic style developed in buildings such as the basilica of Saint-Denis on the outskirts of Paris, Île-de-France (Figs 1–2), under the direction of Abbot Suger (1081–1151)—the style was known as either simply ‘new’, or opus francigenum (literally translates as ‘French work’). The style became known as Gothic in the sixteenth century because certain high-profile figures in the Italian Renaissance railed against the architecture and connected what they perceived to be its crude forms with the Goths that sacked Rome and ‘destroyed’ Classical architecture. During the nineteenth century, critics applied Gothic to more than architecture; they located all types of art under the Gothic label. This broad application of the term wasn’t especially helpful and it is no-longer used. Gothic design, nevertheless, was applied to more than architecture in the medieval period. Applied arts, such as furniture and metalwork, were influenced by, and followed and incorporated the decorative and ornament aspects of Gothic architecture. This post assesses the range of influences that Gothic had upon furniture, in particular by exploring Manchester Cathedral’s woodwork, some of which are the most important examples of surviving medieval woodwork in the North of England. Manchester Cathedral, formerly the Collegiate Church of the City (Fig.3), see here, was ascribed Cathedral status in 1847, and it is grade I listed (Historic England listing number 1218041, see here). It is medieval in foundation, with parts dating to between c.1422 and 1520, however it was restored and rebuilt numerous times in the nineteenth century, and it was notably hit by a shell during WWII; the shell failed to explode. -

Unclassified Fourteenth- Century Purbeck Marble Incised Slabs

Reports of the Research Committee of the Society of Antiquaries of London, No. 60 EARLY INCISED SLABS AND BRASSES FROM THE LONDON MARBLERS This book is published with the generous assistance of The Francis Coales Charitable Trust. EARLY INCISED SLABS AND BRASSES FROM THE LONDON MARBLERS Sally Badham and Malcolm Norris The Society of Antiquaries of London First published 1999 Dedication by In memory of Frank Allen Greenhill MA, FSA, The Society of Antiquaries of London FSA (Scot) (1896 to 1983) Burlington House Piccadilly In carrying out our study of the incised slabs and London WlV OHS related brasses from the thirteenth- and fourteenth- century London marblers' workshops, we have © The Society of Antiquaries of London 1999 drawn very heavily on Greenhill's records. His rubbings of incised slabs, mostly made in the 1920s All Rights Reserved. Except as permitted under current legislation, and 1930s, often show them better preserved than no part of this work may be photocopied, stored in a retrieval they are now and his unpublished notes provide system, published, performed in public, adapted, broadcast, much invaluable background information. Without transmitted, recorded or reproduced in any form or by any means, access to his material, our study would have been less without the prior permission of the copyright owner. complete. For this reason, we wish to dedicate this volume to Greenhill's memory. ISBN 0 854312722 ISSN 0953-7163 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the -

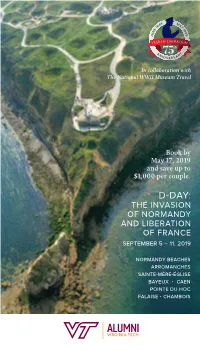

2019 Flagship Vatech Sept5.Indd

In collaboration with The National WWII Museum Travel Book by May 17, 2019 and save up to $1,000 per couple. D-DAY: THE INVASION OF NORMANDY AND LIBERATION OF FRANCE SEPTEMBER 5 – 11, 2019 NORMANDY BEACHES ARROMANCHES SAINTE-MÈRE-ÉGLISE BAYEUX • CAEN POINTE DU HOC FALAISE • CHAMBOIS NORMANDY CHANGES YOU FOREVER Dear Alumni and Friends, Nothing can match learning about the Normandy landings as you visit the ery places where these events unfolded and hear the stories of those who fought there. The story of D-Day and the Allied invasion of Normandy have been at the heart of The National WWII Museum’s mission since they opened their doors as The National D-Day Museum on June 6, 2000, the 56th Anniversary of D-Day. Since then, the Museum in New Orleans has expanded to cover the entire American experience in World War II. The foundation of this institution started with the telling of the American experience on D-Day, and the Normandy travel program is still held in special regard – and is considered to be the very best battlefield tour on the market. Drawing on the historical expertise and extensive archival collection, the Museum’s D-Day tour takes visitors back to June 6, 1944, through a memorable journey from Pegasus Bridge and Sainte-Mère-Église to Omaha Beach and Pointe du Hoc. Along the way, you’ll learn the timeless stories of those who sacrificed everything to pull-off the largest amphibious attack in history, and ultimately secured the freedom we enjoy today. Led by local battlefield guides who are experts in the field, this Normandy travel program offers an exclusive experience that incorporates pieces from the Museum’s oral history and artifact collections into presentations that truly bring history to life. -

The English Claim to Gothic: Contemporary Approaches to an Age-Old Debate (Under the Direction of DR STEFAAN VAN LIEFFERINGE)

ABSTRACT MARY ELIZABETH BLUME The English Claim to Gothic: Contemporary Approaches to an Age-Old Debate (Under the Direction of DR STEFAAN VAN LIEFFERINGE) The Gothic Revival of the nineteenth century in Europe aroused a debate concerning the origin of a style already six centuries old. Besides the underlying quandary of how to define or identify “Gothic” structures, the Victorian revivalists fought vehemently over the national birthright of the style. Although Gothic has been traditionally acknowledged as having French origins, English revivalists insisted on the autonomy of English Gothic as a distinct and independent style of architecture in origin and development. Surprisingly, nearly two centuries later, the debate over Gothic’s nationality persists, though the nationalistic tug-of-war has given way to the more scholarly contest to uncover the style’s authentic origins. Traditionally, scholarship took structural or formal approaches, which struggled to classify structures into rigidly defined periods of formal development. As the Gothic style did not develop in such a cleanly linear fashion, this practice of retrospective labeling took a second place to cultural approaches that consider the Gothic style as a material manifestation of an overarching conscious Gothic cultural movement. Nevertheless, scholars still frequently look to the Isle-de-France when discussing Gothic’s formal and cultural beginnings. Gothic historians have entered a period of reflection upon the field’s historiography, questioning methodological paradigms. This -

Gable Roof, Often Decorated Or Pierced in Victorian Houses

Part E Appendices Village of Maple Heritage Conservation District Plan 141 Appendix A: Glossary of Architectural Terms Italicised words are defined in other entries. ABA rhythm: a pattern of alternating bays. Other rhythms might be ABBA, or AABBAA, for example. Arcade: a running series of arches, supported on piers or columns. Arch: a curved structure over an opening, supported by mutual lateral pressure. Architrave: The lowest division of an entablature. Ashlar: Squared stone masonry laid in regular courses with fine joints. Balustrade: A parapet or guard consisting of balusters supporting a rail or coping. The stair rail on the open side of a household stair is a common example of a balustrade. Barge board: The board along the edge of a gable roof, often decorated or pierced in Victorian houses. Battlement: A notched parapet, like on a castle. Also called castellation. The notches are called embassures or crenelles, and the raised parts are called merlons. Bay: Divisions of a building marked by windows, pilasters, etc. An Ontario cottage with a centre door and windows on either side would be called a 3-bay house with an ABA rhythm. Bay window: A group of windows projecting beyond a main wall. Commonly with angled sides in the Victorian style, and rectangular in Edwardian. Bipartite: In two parts. Blind: An imitation opening on a solid wall is called blind. Thus a blind arch, a blind window, a blind arcade. Board-and-batten: Wood siding consisting of wide vertical boards, the joints of which are covered by narrow vertical strips, or battens. Bond: A pattern of bricklaying in a wall. -

The Bayeux Tapestry

The Bayeux Tapestry The Bayeux Tapestry A Critically Annotated Bibliography John F. Szabo Nicholas E. Kuefler ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • London Published by Rowman & Littlefield A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706 www.rowman.com Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB Copyright © 2015 by John F. Szabo and Nicholas E. Kuefler All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Szabo, John F., 1968– The Bayeux Tapestry : a critically annotated bibliography / John F. Szabo, Nicholas E. Kuefler. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4422-5155-7 (cloth : alk. paper) – ISBN 978-1-4422-5156-4 (ebook) 1. Bayeux tapestry–Bibliography. 2. Great Britain–History–William I, 1066–1087– Bibliography. 3. Hastings, Battle of, England, 1066, in art–Bibliography. I. Kuefler, Nicholas E. II. Title. Z7914.T3S93 2015 [NK3049.B3] 016.74644’204330942–dc23 2015005537 ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992. Printed