The Bayeux Tapestry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Constantia, St

THE AGES DIGITAL LIBRARY REFERENCE CYCLOPEDIA of BIBLICAL, THEOLOGICAL and ECCLESIASTICAL LITERATURE Constantia, St. - Czechowitzky, Martin by James Strong & John McClintock To the Students of the Words, Works and Ways of God: Welcome to the AGES Digital Library. We trust your experience with this and other volumes in the Library fulfills our motto and vision which is our commitment to you: MAKING THE WORDS OF THE WISE AVAILABLE TO ALL — INEXPENSIVELY. AGES Software Rio, WI USA Version 1.0 © 2000 2 Constantia, Saint a martyr at Nuceria, under Nero, is commemorated September 19 in Usuard's Martyrology. Constantianus, Saint abbot and recluse, was born in Auvergne in the beginning of the 6th century, and died A.D. 570. He is commemorated December 1 (Le Cointe, Ann. Eccl. Fran. 1:398, 863). Constantin, Boniface a French theologian, belonging to the Jesuit order, was born at Magni (near Geneva) in 1590, was professor of rhetoric and philosophy at Lyons, and died at Vienne, Dauphine, November 8, 1651. He wrote, Vie de Cl. de Granger Eveque et Prince dae Geneve (Lyons, 1640): — Historiae Sanctorum Angelorum Epitome (ibid. 1652), a singular work upon the history of angels. He also-wrote some other works on theology. See Hoefer, Nouv. Biog. Generale, s.v.; Jocher, Allgemeines Gelehrten- Lexikon, s.v. Constantine (or Constantius), Saint is represented as a bishop, whose deposition occurred at Gap, in France. He is commemorated April 12 (Gallia Christiana 1:454). SEE CONSTANTINIUS. Constantine Of Constantinople deacon and chartophylax of the metropolitan Church of Constantinople, lived before the 8th century. There is a MS. -

View Or Download Full Colour Catalogue May 2021

VIEW OR DOWNLOAD FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE 1986 — 2021 CELEBRATING 35 YEARS Ian Green - Elaine Sunter Managing Director Accounts, Royalties & Promotion & Promotion. ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Orders & General Enquiries To:- Tel (0)1875 814155 email - [email protected] • Website – www.greentrax.com GREENTRAX RECORDINGS LIMITED Cockenzie Business Centre Edinburgh Road, Cockenzie, East Lothian Scotland EH32 0XL tel : 01875 814155 / fax : 01875 813545 THIS IS OUR DOWNLOAD AND VIEW FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE FOR DETAILS OF AVAILABILITY AND ON WHICH FORMATS (CD AND OR DOWNLOAD/STREAMING) SEE OUR DOWNLOAD TEXT (NUMERICAL LIST) CATALOGUE (BELOW). AWARDS AND HONOURS BESTOWED ON GREENTRAX RECORDINGS AND Dr IAN GREEN Honorary Degree of Doctorate of Music from the Royal Conservatoire, Glasgow (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – The Hamish Henderson Award for Services to Traditional Music (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – Hall of Fame (Ian Green) East Lothian Business Annual Achievement Award For Good Business Practises (Greentrax Recordings) Midlothian and East Lothian Chamber of Commerce – Local Business Hero Award (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Hands Up For Trad – Landmark Award (Greentrax Recordings) Featured on Scottish Television’s ‘Artery’ Series (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Honorary Member of The Traditional Music and Song Association of Scotland and Haddington Pipe Band (Ian Green) ‘Fuzz to Folk – Trax of My Life’ – Biography of Ian Green Published by Luath Press. Music Type Groups : Traditional & Contemporary, Instrumental -

Romantic Textualities, 22

R OMANTICT EXTUALITIES LITERATURE AND PRINT CULTURE, 1780–1840 • ISSN 1748-0116 ◆ ISSUE 22 ◆ SPRING 2017 ◆ SPECIAL ISSUE : FOUR NATIONS FICTION BY WOMEN, 1789–1830 ◆ www.romtext.org.uk ◆ CARDIFF UNIVERSITY PRESS ◆ Romantic Textualities: Literature and Print Culture, 1780–1840, 22 (Spring 2017) Available online at <www.romtext.org.uk/>; archive of record at <https://publications.cardiffuniversitypress.org/index.php/RomText>. Journal DOI: 10.18573/issn.1748-0116 ◆ Issue DOI: 10.18573/n.2017.10148 Romantic Textualities is an open access journal, which means that all content is available without charge to the user or his/her institution. You are allowed to read, download, copy, distribute, print, search or link to the full texts of the articles in this journal without asking prior permission from either the publisher or the author. Unless otherwise noted, the material contained in this journal is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 (cc by-nc-nd) Interna- tional License. See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ for more information. Origi- nal copyright remains with the contributing author and a citation should be made when the article is quoted, used or referred to in another work. C b n d Romantic Textualities is an imprint of Cardiff University Press, an innovative open-access publisher of academic research, where ‘open-access’ means free for both readers and writers. Find out more about the press at cardiffuniversitypress.org. Editors: Anthony Mandal, Cardiff University Maximiliaan -

Cora Ginsburg Catalogue 2015

CORA GINSBURG LLC TITI HALLE OWNER A Catalogue of exquisite & rare works of art including 17th to 20th century costume textiles & needlework 2015 by appointment 19 East 74th Street tel 212-744-1352 New York, NY 10021 fax 212-879-1601 www.coraginsburg.com [email protected] NEEDLEWORK SWEET BAG OR SACHET English, third quarter of the 17th century For residents of seventeenth-century England, life was pungent. In order to combat the unpleasant odors emanating from open sewers, insufficiently bathed neighbors, and, from time to time, the bodies of plague victims, a variety of perfumed goods such as fans, handkerchiefs, gloves, and “sweet bags” were available for purchase. The tradition of offering embroidered sweet bags containing gifts of small scented objects, herbs, or money began in the mid-sixteenth century. Typically, they are about five inches square with a drawstring closure at the top and two to three covered drops at the bottom. Economical housewives could even create their own perfumed mixtures to put inside. A 1621 recipe “to make sweete bags with little cost” reads: Take the buttons of Roses dryed and watered with Rosewater three or foure times put them Muske powder of cloves Sinamon and a little mace mingle the roses and them together and putt them in little bags of Linnen with Powder. The present object has recently been identified as a rare surviving example of a large-format sweet bag, sometimes referred to as a “sachet.” Lined with blue silk taffeta, the verso of the central canvas section contains two flat slit pockets, opening on the long side, into which sprigs of herbs or sachets filled with perfumed powders could be slipped to scent a wardrobe or chest. -

Virginia Theological Seminary Gothic France: 21-31 May 2021

Virginia Theological Seminary Gothic France: 21-31 May 2021 SAMPLE OF PROGRAM* Day 1: Friday, May 21, 2021 Arrival in Paris on your own Group Welcome Dinner in a restaurant Lodging in a 4 * boutique hotel in the 5th or 6th arrondissement of Paris (Hotel des Saint-Pères or similar) Day 2: Saturday May 22, 2021 Meet your private tour bus and 2 guides at your hotel for a guided day in Paris. Guided visit of the church of St Pierre de Montmartre, one of the oldest extant churches in Paris, and the Sacré Coeur Basilica with its mosaic of Christ in Glory. Lunch on your own in historic Montmartre After lunch, meet your tour bus for a guided visit of the St Denis Basilica to learn about the birth of Gothic architecture Return to the hotel at the end of the day. Dinner on your own Lodging in a 4 * boutique hotel in the 5th or 6th arrondissement of Paris (Hotel des Saint-Pères or similar) Day 3: Sunday, May 23, 2021 Meet your private tour bus and your 2 guides in front of your hotel for a day trip to Chartres. Guided tour of Notre Dame de Chartres Cathedral, a unique example of early gothic architecture, th and its 13 century Labyrinth Group Lunch in a restaurant Free time to explore the town of Chartres Return to Paris with your tour bus at the end of the day Dinner on your own Lodging in a 4 * boutique hotel in the 5th or 6th arrondissement of Paris (Hotel des Saint-Pères or similar) Day 4: Monday, May 24, 2021 Meet your 2 guides at your hotel for a guided day in Paris (transport pass provided) Guided visit of Notre Dame Cathedral (the exterior), an iconic masterpiece of Gothic architecture, ravaged by fire in April 2019. -

Bibliography

Bibliography Many books were read and researched in the compilation of Binford, L. R, 1983, Working at Archaeology. Academic Press, The Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology: New York. Binford, L. R, and Binford, S. R (eds.), 1968, New Perspectives in American Museum of Natural History, 1993, The First Humans. Archaeology. Aldine, Chicago. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Braidwood, R 1.,1960, Archaeologists and What They Do. Franklin American Museum of Natural History, 1993, People of the Stone Watts, New York. Age. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Branigan, Keith (ed.), 1982, The Atlas ofArchaeology. St. Martin's, American Museum of Natural History, 1994, New World and Pacific New York. Civilizations. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Bray, w., and Tump, D., 1972, Penguin Dictionary ofArchaeology. American Museum of Natural History, 1994, Old World Civiliza Penguin, New York. tions. HarperSanFrancisco, San Francisco. Brennan, L., 1973, Beginner's Guide to Archaeology. Stackpole Ashmore, w., and Sharer, R. J., 1988, Discovering Our Past: A Brief Books, Harrisburg, PA. Introduction to Archaeology. Mayfield, Mountain View, CA. Broderick, M., and Morton, A. A., 1924, A Concise Dictionary of Atkinson, R J. C., 1985, Field Archaeology, 2d ed. Hyperion, New Egyptian Archaeology. Ares Publishers, Chicago. York. Brothwell, D., 1963, Digging Up Bones: The Excavation, Treatment Bacon, E. (ed.), 1976, The Great Archaeologists. Bobbs-Merrill, and Study ofHuman Skeletal Remains. British Museum, London. New York. Brothwell, D., and Higgs, E. (eds.), 1969, Science in Archaeology, Bahn, P., 1993, Collins Dictionary of Archaeology. ABC-CLIO, 2d ed. Thames and Hudson, London. Santa Barbara, CA. Budge, E. A. Wallis, 1929, The Rosetta Stone. Dover, New York. Bahn, P. -

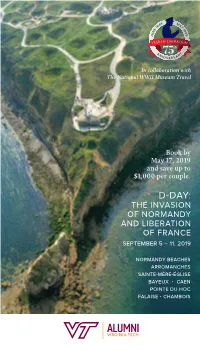

2019 Flagship Vatech Sept5.Indd

In collaboration with The National WWII Museum Travel Book by May 17, 2019 and save up to $1,000 per couple. D-DAY: THE INVASION OF NORMANDY AND LIBERATION OF FRANCE SEPTEMBER 5 – 11, 2019 NORMANDY BEACHES ARROMANCHES SAINTE-MÈRE-ÉGLISE BAYEUX • CAEN POINTE DU HOC FALAISE • CHAMBOIS NORMANDY CHANGES YOU FOREVER Dear Alumni and Friends, Nothing can match learning about the Normandy landings as you visit the ery places where these events unfolded and hear the stories of those who fought there. The story of D-Day and the Allied invasion of Normandy have been at the heart of The National WWII Museum’s mission since they opened their doors as The National D-Day Museum on June 6, 2000, the 56th Anniversary of D-Day. Since then, the Museum in New Orleans has expanded to cover the entire American experience in World War II. The foundation of this institution started with the telling of the American experience on D-Day, and the Normandy travel program is still held in special regard – and is considered to be the very best battlefield tour on the market. Drawing on the historical expertise and extensive archival collection, the Museum’s D-Day tour takes visitors back to June 6, 1944, through a memorable journey from Pegasus Bridge and Sainte-Mère-Église to Omaha Beach and Pointe du Hoc. Along the way, you’ll learn the timeless stories of those who sacrificed everything to pull-off the largest amphibious attack in history, and ultimately secured the freedom we enjoy today. Led by local battlefield guides who are experts in the field, this Normandy travel program offers an exclusive experience that incorporates pieces from the Museum’s oral history and artifact collections into presentations that truly bring history to life. -

Crewel Embroidery 0F Colonial New England

o o . 1‘ ‘ lb ‘ \w‘.‘ v ‘ " O . .1' '-' «7A :1. 90;": “W;ul.\u’$31.?l'“.‘ 1),. 3:10; 'M " d5‘_);”: ”‘22. ‘ '11“. 5"? $0.053“: . ~ .t"""\" 0‘70' ' ‘. ""7"! ( J::T.m4‘u '.""‘:.O-c :cnou ~11 ‘5'. u o. _'.‘ "' "‘:"-: .t-‘. _ n J; :ln'. ‘“:.;.’ ‘u‘ 9“ .‘ A.“ '. .. *“." " V'W‘ ’:".I|\~u"oOI(|‘. ""h’" '...Iigv-I . 01.11 f"-"'-":""‘°uo‘f.‘ .. - . ‘ p...‘ ‘I . ‘ a " . ...<o CREWEL ... EMBROIDERY THE Thesis MICHIGAN ENVIRONMENTAL MARY for 0F LYNNE the STATE COLONIAL 1975 Degree RICHARDS UNIVERSIIY INFLUENCES ovo- Of NEW M. cOc "9...! A ENGLAND -~ 0 ’Ipup~ ”‘0... l 00"! . AND I'ocumnmnwwwvwv- - Q . o . IIIII IIIIIIIOO PLACE II RETURN BOX to remove this Moat from yout record. To AVOID FINES Mum on or More data duo. DATE DUE DATE DUE DATE DUE — LI- * Om MSU Is An Affirmative MINI/Emil Opportunity Institution Wanna-9.1 ABSTRACT CREWEL EMBROIDERY OF COLONIAL NEw ENGLAND AND THE ENVIRONMENTAL INFLUENCES By Mary Lynne Richards The purposes of this study were: 1) to describe the characteristic colors, stitches and designs found in crewel embroidery created within New England during the colonial period, 2) to analyze these characteris- tics in relation to the dates and locations of the sample embroideries, and 3) to analyze the characteristic designs in relation to aspects of the colonial New England physical environment. The sample was composed of fifty crewel embroidered items, believed to have been created between 1620 and 1781, within the geographic boundaries of New England. A data sheet, plus color slides or black and white sketches, were used to record information pertaining to each embroidered item. -

August 2021.Indd

Search Press Ltd August 2021 The Complete Book of patchwork, Quilting & Appliqué by Linda Seward www.searchpress.com/trade SEARCH PRESS LIMITED The world’s finest art and craft books ADVANCE INFORMATION Drawing - A Complete Guide: Nature Giovanni Civardi Publication 31st August 2021 Price £12.99 ISBN 9781782218807 Format Paperback 218 x 152 mm Extent 400 pages Illustrations 960 Black & white illustrations Publisher Search Press Classification Drawing & sketching BIC CODE/S AFF, WFA SALES REGIONS WORLD Key Selling Points Giovanni Civardi is a best-selling author and artist who has sold over 600,000 books worldwide No-nonsense advice on the key skills for drawing nature – from understanding perspective to capturing light and shade Subjects include favourites such as country scenes, flowers, fruit, animals and more Perfect book for both beginner and experienced artists looking for an inspirational yet informative introduction to drawing natural subjects This guide is bind-up of seven books from Search Press’s successful Art of Drawing series: Drawing Techniques; Understanding Perspective; Drawing Scenery; Drawing Light & Shade; Flowers, Fruit & Vegetables; Drawing Pets; and Wild Animals. Description Learn to draw the natural world with this inspiring and accessible guide by master-artist Giovanni Civardi. Beginning with the key drawing methods and essential materials you’ll need to start your artistic journey, along with advice on drawing perspective as well as light and shade, learn to sketch country scenes, fruit, vegetables, animals and more. Throughout you’ll find hundreds of helpful and practical illustrations, along with stunning examples of Civardi’s work that exemplify his favourite techniques for capturing the natural world. -

Textileartscouncil William Morrisbibliography V2

TAC Virtual Travels: The Arts and Crafts Heritage of William and May Morris, August 2020 Bibliography Compiled by Ellin Klor, Textile Arts Council Board. ([email protected]) William Morris and Morris & Co. 1. Sites A. Standen House East Grinstead, (National Trust) https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/standen-house-and-garden/features/discover-the- house-and-collections-at-standen Arts and Crafts family home with Morris & Co. interiors, set in a beautiful hillside garden. Designed by Philip Webb, taking inspiration from the local Sussex vernacular, and furnished by Morris & Co., Standen was the Beales’ country retreat from 1894. 1. Heni Talks- “William Morris: Useful Beauty in the Home” https://henitalks.com/talks/william-morris-useful-beauty/ A combination exploration of William Morris and the origins of the Arts & Crafts movement and tour of Standen House as the focus by art historian Abigail Harrison Moore. a. Bio of Dr. Harrison Moore- https://theconversation.com/profiles/abigail- harrison-moore-121445 B. Kelmscott Manor, Lechlade - Managed by the London Society of Antiquaries. https://www.sal.org.uk/kelmscott-manor/ Closed through 2020 for restoration. C. Red House, Bexleyheath - (National Trust) https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/red-house/history-at-red-house When Morris and Webb designed Red House and eschewed all unnecessary decoration, instead choosing to champion utility of design, they gave expression to what would become known as the Arts and Crafts Movement. Morris’ work as both a designer and a socialist were intrinsically linked, as the creation of the Arts and Crafts Movement attests. D. William Morris Gallery - Lloyd Park, Forest Road, Walthamstow, London, E17 https://www.wmgallery.org.uk/ From 1848 to 1856, the house was the family home of William Morris (1834-1896), the designer, craftsman, writer, conservationist and socialist. -

Pagan to Christian Slides As Printable Handout

23/08/2018 Transition From Pagan To Christian William Sterling Fragments of a Colossal Bronze Statue of Constantine, Rome Hinton St Mary Mosaic in the British Museum c. 1985 Bellerophon ↑ and Jesus ↓ Today there are statues and a Café in the same position “Although we speak of a religious crisis in the late Roman Empire, there is little, real sign that the transition from paganism to Edward Gibbon by Christianity was fundamentally Reynolds difficult.” Dr J P C Kent of the Museum’s Coins and Medals Department “The World of Late Antiquity” “Decorative art shows no clear division between paganism and “the pure and genuine influence of Christianity may be traced in its Christianity” beneficial, though imperfect, effects on the barbarian proselytes of the North. If the decline of the Roman empire was hastened by the K S Painter “Gold and Silver from conversion of Constantine, his victorious religion broke the violence of the Late Roman World Fourth-Fifth the fall, and mollified the ferocious temper of the conquerors.” Centuries.” 1 23/08/2018 “The new religion and new ecclesiastical practices were a steady focal point around which the new ideological currents and “The Christian culture that would social realignments revolved, as emerge in late antiquity carried Christianity gradually penetrated more of the genes of its “pagan” the various social strata before ancestry than of the peculiarly becoming the official religion of the Christian mutations.” state. At the same time, important aspects of the classical spirit and Wayne A Meeks “Social and ecclesial civilisation still survived to life of the earliest Christians” complete our picture of late antiquity.” Eutychia Kourkoutidou-Nicolaidou “From the Elysian Fields to the Christian paradise” “I don’t think there was ever anything wrong with the ancient world. -

Abbot Suger's Consecrations of the Abbey Church of St. Denis

DE CONSECRATIONIBUS: ABBOT SUGER’S CONSECRATIONS OF THE ABBEY CHURCH OF ST. DENIS by Elizabeth R. Drennon A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Boise State University August 2016 © 2016 Elizabeth R. Drennon ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BOISE STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COLLEGE DEFENSE COMMITTEE AND FINAL READING APPROVALS of the thesis submitted by Elizabeth R. Drennon Thesis Title: De Consecrationibus: Abbot Suger’s Consecrations of the Abbey Church of St. Denis Date of Final Oral Examination: 15 June 2016 The following individuals read and discussed the thesis submitted by student Elizabeth R. Drennon, and they evaluated her presentation and response to questions during the final oral examination. They found that the student passed the final oral examination. Lisa McClain, Ph.D. Chair, Supervisory Committee Erik J. Hadley, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee Katherine V. Huntley, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee The final reading approval of the thesis was granted by Lisa McClain, Ph.D., Chair of the Supervisory Committee. The thesis was approved for the Graduate College by Jodi Chilson, M.F.A., Coordinator of Theses and Dissertations. DEDICATION I dedicate this to my family, who believed I could do this and who tolerated my child-like enthusiasm, strange mumblings in Latin, and sudden outbursts of enlightenment throughout this process. Your faith in me and your support, both financially and emotionally, made this possible. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Lisa McClain for her support, patience, editing advice, and guidance throughout this process. I simply could not have found a better mentor.