English Legal History Mon., 13 Sep

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parliamentary Immunity

Parliamentary Immunity A Comprehensive Study of the Systems of Parliamentary Immunity of the United Kingdom, France, and the Netherlands in a European Context Parliamentary Immunity A Comprehensive Study of the Systems of Parliamentary Immunity of the United Kingdom, France, and the Netherlands in a European Context DISSERTATION to obtain the degree of Doctor at the Maastricht University, on the authority of the Rector Magnificus, Prof. dr. L.L.G. Soete in accordance with the decision of the Board of Deans, to be defended in public on Thursday 26 September 2013, at 16.00 hours by Sascha Hardt Supervisor: Prof. mr. L.F.M. Verhey (Leiden University, formerly Maastricht University) Co-Supervisor: Dr. Ph. Kiiver Assessment Committee: Prof. dr. J.Th.J. van den Berg Prof. dr. M. Claes (Chair) Prof. dr. C. Guérin-Bargues (Université d’Orléans) Prof. mr. A.W. Heringa Prof. D. Oliver, MA, PhD, LLD Barrister, FBA (Univeristy College London) Cover photograph © Andreas Altenburger - Dreamstime.com Layout by Marina Jodogne. A commercial edition of this PhD-thesis will be published by Intersentia in the Ius Commune Europaeum Series, No. 119 under ISBN 978-1-78068-191-7. Für Danielle ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As I have been told, the idea that I could write a doctoral dissertation first occurred to Philipp Kiiver when he was supervising my bachelor thesis in 2007. At that time, I may well have dreamed of a PhD position, but I was far from having any actual plans, let alone actively pursuing them. Yet, not a year later, Luc Verhey and Philipp Kiiver asked me whether I was interested to join the newly founded Montesquieu Institute Maastricht as a PhD researcher. -

Report of Proceedings of Tynwald Court

REPORT OF PROCEEDINGS OF TYNWALD COURT Douglas, Tuesday, February 17, 1976 Present: The Governor (Sir John ing Bill; Social Security Legislation Paul,- G.C.M.G., O.B.E., M .C.), In the (Application) (Amendment) Bill; and Council: the Lord Bishop (the Rt. Rev. the Animal Offences Bill. If the Court Vernon Nicholls), the Attorney General concurs we will continue with our ('Mr. J. W. Corrin), Messrs. J. B. •business while these are being signed. Bolton, O.B.E., G. T. Crellin, E. N. It was agreed. Crowe, O.B.E., R. E. S. Kerruish, G. V. H. Kneale, J. C. ¡Nivison, W. E. Quayle, A. H. Sim'cocks, M.B.E., with PAPERS LAID (BEFORE THE COURT Mr. P. J. Hulme, Clerk oi the Council. The Governor: Item 3, I call upon In the Keys : The Speaker (Mr. H. C. the Clerk to lay papers. Kerruish, O.B.E.), Messrs. R. J. G. The Clerk: I lay before the C ourt:— Anderson, H. D. C. MacLeod, G. M. Kermeen, J. C. Clucas, P. Radcliffe, Governor’s Duties and Powers — J. R. Creer, E. Ranson, P. A. Spittall, Third Interim. Report o f the Select T. C. Faragher, N. Q. Cringle, E. G. Committee of Tynwald. Lowey, Mrs. E. C. Quayle, Messrs. W- Cremation Act 1957 — Cremation A. Moore, J.J. Bell, E. M. Ward, B.E.M., Regulations 1976. E. C. Irving, Miss K. E. Cowin, Mr. Value Added Tax — Value Added G. A. Devereau, Mrs. B. Q. Hanson, Tax (Isle of Man) (Fuel and Power) Messrs. R. MacDonald, P. -

Whyte, Alasdair C. (2017) Settlement-Names and Society: Analysis of the Medieval Districts of Forsa and Moloros in the Parish of Torosay, Mull

Whyte, Alasdair C. (2017) Settlement-names and society: analysis of the medieval districts of Forsa and Moloros in the parish of Torosay, Mull. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/8224/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten:Theses http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Settlement-Names and Society: analysis of the medieval districts of Forsa and Moloros in the parish of Torosay, Mull. Alasdair C. Whyte MA MRes Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Celtic and Gaelic | Ceiltis is Gàidhlig School of Humanities | Sgoil nan Daonnachdan College of Arts | Colaiste nan Ealain University of Glasgow | Oilthigh Ghlaschu May 2017 © Alasdair C. Whyte 2017 2 ABSTRACT This is a study of settlement and society in the parish of Torosay on the Inner Hebridean island of Mull, through the earliest known settlement-names of two of its medieval districts: Forsa and Moloros.1 The earliest settlement-names, 35 in total, were coined in two languages: Gaelic and Old Norse (hereafter abbreviated to ON) (see Abbreviations, below). -

Early Medieval Dykes (400 to 850 Ad)

EARLY MEDIEVAL DYKES (400 TO 850 AD) A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2015 Erik Grigg School of Arts, Languages and Cultures Contents Table of figures ................................................................................................ 3 Abstract ........................................................................................................... 6 Declaration ...................................................................................................... 7 Acknowledgments ........................................................................................... 9 1 INTRODUCTION AND METHODOLOGY ................................................. 10 1.1 The history of dyke studies ................................................................. 13 1.2 The methodology used to analyse dykes ............................................ 26 2 THE CHARACTERISTICS OF THE DYKES ............................................. 36 2.1 Identification and classification ........................................................... 37 2.2 Tables ................................................................................................. 39 2.3 Probable early-medieval dykes ........................................................... 42 2.4 Possible early-medieval dykes ........................................................... 48 2.5 Probable rebuilt prehistoric or Roman dykes ...................................... 51 2.6 Probable reused prehistoric -

Viking Wirral … and the Battle of Brunanburh Professor Steve Harding

Viking Wirral … and the Battle of Brunanburh Professor Steve Harding Neil Oliver, “History of Scotland” BBC2, 2009 “ The many armies, tens of thousands of warriors clashed at the site known as Brunanburh where the Mersey Estuary enters the sea . For decades afterwards it was simply known called the Great Battle. This was the mother of all dark-age bloodbaths and would define the shape of Britain into the modern era. Althouggg,h Athelstan emerged victorious, the resistance of the northern alliance had put an end to his dream of conquering the whole of Britain. This had been a battle for Britain, one of the most important battles in British historyyy and yet today ypp few people have even heard of it. 937 doesn’t quite have the ring of 1066 and yet Brunanburh was about much more than blood and conquest. This was a showdown between two very different ethnic identities – a Norse-Celtic alliance versus Anglo-Saxon. It aimed to settle once and for all whether Britain would be controlled by a single Imperial power or remain several separate kingdoms. A split in perceptions which, like it or not, is still with us today”. Some of the people who’ve been trying to sort it out Nic k Hig ham Pau l Cav ill Mic hae l Woo d John McNeal Dodgson 1928-1990 Plan •Background of Brunanburh • Evidence for Wirral location for the battle • If it did happen in Wirra l, w here is a like ly site for the battle • Consequences of the Battle for Wirral – and Britain Background of Brunanburh “Cherchez la Femme!” Ann Anderson (1964) The Story of Bromborough •TheThe Viking -

The Anglo-Saxon Period of English Law

THE ANGLO-SAXON PERIOD OF ENGLISH LAW We find the proper starting point for the history of English law in what are known as Anglo-Saxon times. Not only does there seem to be no proof, or evidence of the existence of any Celtic element in any appreciable measure in our law, but also, notwithstanding the fact that the Roman occupation of Britain had lasted some four hundred years when it terminated in A. D. 410, the last word of scholarship does not bring to light any trace of the law of Imperial Rome, as distinct from the precepts and traditions of the Roman Church, in the earliest Anglo- Saxon documents. That the written dooms of our kings are the purest specimen of pure Germanic law, has been the verdict of one scholar after another. Professor Maitland tells us that: "The Anglo-Saxon laws that have come down to us (and we have no reason to fear the loss of much beyond some dooms of the Mercian Offa) are best studied as members of a large Teutonic family. Those that proceed from the Kent and Wessex of the seventh century are closely related to the Continental folk-laws. Their next of kin seem to be the Lex Saxonum and the laws of the Lom- bards."1 Whatever is Roman in them is ecclesiastical, the system which in course of time was organized as the Canon law. Nor are there in England any traces of any Romani who are being suffered to live under their own law by their Teutonic rulers. -

Violence, Christianity, and the Anglo-Saxon Charms Laurajan G

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1-1-2011 Violence, Christianity, And The Anglo-Saxon Charms Laurajan G. Gallardo Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Gallardo, Laurajan G., "Violence, Christianity, And The Anglo-Saxon Charms" (2011). Masters Theses. 293. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/293 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. *****US Copyright Notice***** No further reproduction or distribution of this copy is permitted by electronic transmission or any other means. The user should review the copyright notice on the following scanned image(s) contained in the original work from which this electronic copy was made. Section 108: United States Copyright Law The copyright law of the United States [Title 17, United States Code] governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the reproduction is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research. If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of "fair use," that use may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. -

The Anglo-Saxons

The Anglo-Saxons WALT: Understand key information about Anglo-Saxon times. When? Who can remember when the Romans left Britain? In around 410AD, after 300 years here, the Romans returned to Rome. Who did that leave here in Britain? The Britons were left in what is today England and Wales. The Picts and Scots lived in modern-day Scotland and kept trying to take over British land. When did the Anglo-Saxons arrive? They had been coming over since around 300AD to trade, but they began settling in around 450AD. Who? ‘Anglo-Saxons’ is the name historians have given to the settlers of Britain from 450AD. They are actually made up of 4 distinct tribes, who arrived at around the same time. The tribes were separately known as the Angles, Saxons, Jutes and Frisians. Where did they come from? Do you know what these places are called today and who lives there? Where did they come from? The tribes came from the area that is today known as Denmark, Germany and the Netherlands. These fearsome warriors rowed across the North Sea in wooden boats to England and forced the tribes in Britain to flee their homes. (We will look at their settlements in another lesson.) Within a few centuries, the land they had invaded was known as England, after the Angles. The Anglo-Saxons were warrior- farmers. (We will think about possible reasons for them coming to Britain in another lesson.) The Anglo-Saxons were tall, fair- haired men, armed with swords and spears and round shields. Their other skills consisted of hunting, farming, textile production and leather working. -

International Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol

International Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 7, No. 3, September 2020 doi:10.30845/ijll.v7n3p2 Skaldic Panegyric and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Poem on the Redemption of the Five Boroughs Leading Researcher Inna Matyushina Russian State University for the Humanities Miusskaya Ploshchad korpus 6, Moscow Russia, 125047 Honorary Professor, University of Exeter Queen's Building, The Queen's Drive Streatham Campus, Exeter, EX4 4QJ Summary: The paper attempts to reveal the affinities between skaldic panegyric poetry and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle poem on the ‘Redemption of the Five Boroughs’ included into four manuscripts (Parker, Worcester and both Abingdon) for the year 942. The thirteen lines of the Chronicle poem are laden with toponyms and ethnonyms, prompting scholars to suggest that its main function is mnemonic. However comparison with skaldic drápur points to the communicative aim of the lists of toponyms and ethnonyms, whose function is to mark the restoration of the space defining the historical significance of Edmund’s victory. The Chronicle poem unites the motifs of glory, spatial conquest and protection of land which are also present in Sighvat’s Knútsdrápa (SkP I 660. 9. 1-8), bearing thematic, situational, structural and functional affinity with the former. Like that of Knútsdrápa, the function of the Chronicle poem is to glorify the ruler by formally reconstructing space. The poem, which, unlike most Anglo-Saxon poetry, is centred not on a past but on a contemporary event, is encomium regis, traditional for skaldic poetry. ‘The Redemption of the Five Boroughs’ can be called an Anglo-Saxon equivalent of erfidrápa, directed to posterity and ensuring eternal fame for the ruler who reconstructed the spatial identity of his kingdom. -

When Did the Anglo-Saxons Invade Britain?

History When did the Anglo-Saxons invade Britain? Grammarsaurus www.grammarsaurus.co.uk 11 Anglo-Saxon Invasion In the year 350, the Anglo-Saxons tried to invade Britain. At this time, the Romans ruled Britain. The Anglo-Saxons raided the south and east shores of England. The Romans were not happy and fought back. The Anglo Saxons retreated and left. www.grammarsaurus.co.uk 21 Anglo-Saxon Invasion Around the year 410, the last Roman soldiers left Britain. They had not trained the British to defend themselves therefore Britain no longer had a strong army to defend it from the invaders. There were many battles between Anglo-Saxons and Britons and the Anglo-Saxons succeeded. More and more Anglo-Saxons arrived to take land for themselves. It is for this reason that the time of the Anglo-Saxons is usually thought of as beginning about AD 450. Georgians Pre-History Iron Age Romans Vikings Tudors Modern 43 410 790 1603 1837 1901 1714 1066 1485 AD c.700 BC c.AD c.AD AD AD AD AD AD AD AD AD Anglo-Saxons Medieval Stuarts Victorians www.grammarsaurus.co.uk 31 Who were the Anglo-Saxons? The Anglo-Saxons were made up of three groups of people from Germany, Denmark and The Netherlands. The groups were named the Angles, the Saxons, and the Jutes. The Angles and the Saxon tribes were the largest of the three attacking tribes and so we often know them as Anglo-Saxons. They all shared the same language but were each ruled by different strong warriors. -

Kingdom of Strathclyde from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Kingdom of Strathclyde From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Strathclyde (lit. "Strath of the Clyde"), originally Brythonic Ystrad Clud, was one of the early medieval kingdoms of the Kingdom of Strathclyde Celtic people called the Britons in the Hen Ogledd, the Teyrnas Ystrad Clut Brythonic-speaking parts of what is now southern Scotland and northern England. The kingdom developed during the ← 5th century–11th → post-Roman period. It is also known as Alt Clut, the Brythonic century name for Dumbarton Rock, the medieval capital of the region. It may have had its origins with the Damnonii people of Ptolemy's Geographia. The language of Strathclyde, and that of the Britons in surrounding areas under non-native rulership, is known as Cumbric, a dialect or language closely related to Old Welsh. Place-name and archaeological evidence points to some settlement by Norse or Norse–Gaels in the Viking Age, although to a lesser degree than in neighbouring Galloway. A small number of Anglian place-names show some limited settlement by incomers from Northumbria prior to the Norse settlement. Due to the series of language changes in the area, it is not possible to say whether any Goidelic settlement took place before Gaelic was introduced in the High Middle Ages. After the sack of Dumbarton Rock by a Viking army from Dublin in 870, the name Strathclyde comes into use, perhaps reflecting a move of the centre of the kingdom to Govan. In the same period, it was also referred to as Cumbria, and its inhabitants as Cumbrians. During the High Middle Ages, the area was conquered by the Kingdom of Alba, becoming part of The core of Strathclyde is the strath of the River Clyde. -

The Demo Version

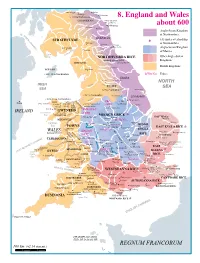

Æbucurnig Dynbær Edinburgh Coldingham c. 638 to Northumbria 8. England and Wales GODODDIN HOLY ISLAND Lindisfarne Tuidi Bebbanburg about 600 Old Melrose Ad Gefring Anglo-Saxon Kingdom NORTH CHANNEL of Northumbria BERNICIA STRATHCLYDE 633 under overlordship Buthcæster Corebricg Gyruum * of Northumbria æt Rægeheafde Mote of Mark Tyne Anglo-Saxon Kingdom Caerluel of Mercia Wear Luce Solway Firth Bay NORTHHYMBRA RICE Other Anglo-Saxon united about 604 Kingdoms Streonæshalch RHEGED Tese Cetreht British kingdoms MANAW Hefresham c 624–33 to Northumbria Rye MYRCNA Tribes DEIRA Ilecliue Eoforwic NORTH IRISH Aire Rippel ELMET Ouse SEA SEA 627 to Northumbria æt Bearwe Humbre c 627 to Northumbria Trent Ouestræfeld LINDESEGE c 624–33 to Northumbria TEGEINGL Gæignesburh Rhuddlan Mærse PEC- c 600 Dublin MÔN HOLY ISLAND Llanfaes Deganwy c 627 to Northumbria SÆTE to Mercia Lindcylene RHOS Saint Legaceaster Bangor Asaph Cair Segeint to Badecarnwiellon GWYNEDD WREOCAN- IRELAND Caernarvon SÆTE Bay DUNODING MIERCNA RICE Rapendun The Wash c 700 to Mercia * Usa NORTHFOLC Byrtun Elmham MEIRIONNYDD MYRCNA Northwic Cardigan Rochecestre Liccidfeld Stanford Walle TOMSÆTE MIDDIL Bay POWYS Medeshamstede Tamoworthig Ligoraceaster EAST ENGLA RICE Sæfern PENCERSÆTE WATLING STREET ENGLA * WALES MAGON- Theodford Llanbadarn Fawr GWERTH-MAELIENYDD Dommoceaster (?) RYNION RICE SÆTE Huntandun SUTHFOLC Hamtun c 656 to Mercia Beodericsworth CEREDIGION Weogornaceaster Bedanford Grantanbrycg BUELLT ELFAEL HECANAS Persore Tovecestre Headleage Rendlæsham Eofeshamm + Hereford c 600 GipeswicSutton Hoo EUIAS Wincelcumb to Mercia EAST PEBIDIOG ERGING Buccingahamm Sture mutha Saint Davids BRYCHEINIOG Gleawanceaster HWICCE Heorotford SEAXNA SAINT GEORGE’SSaint CHANNEL DYFED 577 to Wessex Ægelesburg * Brides GWENT 628 to Mercia Wæclingaceaster Hetfelle RICE Ythancæstir Llanddowror Waltham Bay Cirenceaster Dorchecestre GLYWYSING Caerwent Wealingaford WÆCLINGAS c.