Kingdom of Strathclyde from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glasgow and the Clyde Valley Housing Need and Demand Assessment Technical Report 05

Glasgow and the Clyde Valley Housing Need and Demand Assessment Technical Report 05 Affordability Trends: House Prices, Rent and Incomes May 2015 Glasgow and the Clyde Valley Housing Market Partnership Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. House Price Analysis 2 3. Conurbation HMA Analysis 5 3.1 All Relevant Sales 3.2 New Build Sales 3.3 Resales 3.4 Volume of Sales 3.5 Conurbation HMA: Commentary 4. Central Conurbation HMA Analysis 11 4.1 All Relevant Sales 4.2 New Build Sales 4.3 Resales 4.4 Volume of Sales 4.5 Central Conurbation HMA: Commentary 5. Eastern Conurbation HMA Analysis 16 5.1 All Relevant Sales 5.2 New Build Sales 5.3 Resales 5.4 Volume of Sales 5.5 Eastern Conurbation HMA: Commentary 6. Discrete HMA Analysis: 21 Inverclyde and Dumbarton and Vale of Leven HMA 6.1 All Relevant Sales 6.2 New Build Sales 6.3 Resales 6.4 Volume of Sales 7. Trend Based Analysis: House Price to Incomes 25 7.1 House Prices (Local Authority) 7.2 Incomes (Local Authority) 7.3 Ratio of house price to income trends 2008-2012 8. Rent 31 8.1 Affordability - Private Rent 8.2 Affordability - Social Rent 9. Affordability Analysis: Summary of Key Issues 35 9.1 Mean House Prices 9.2 Lower Quartile House Prices 9.3 New Build House Prices 9.4 Price Variations 9.5 Volume of Sales 9.6 House Prices: Summary 9.7 Trend Based analysis of house price to incomes 9.8 Private Renting 9.9 Affordability - Social Rent 10. -

Settled in Court

SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI Settled in Court? SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI An Inspection of SWSI SWSI SWSI Social Work Services at SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI Four Sheriff Courts SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SOCIAL WORK SERVICES INSPECTORATE SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI 2001 SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI SWSI Settled in Court? An Inspection of Social Work Services at Four Sheriff Courts SOCIAL WORK SERVICES INSPECTORATE 2001 The Social Work Services Inspectorate Saughton House Broomhouse Drive Edinburgh EH11 3XD CONTENTS Introduction 1 Background Purposes 1 Method 2 Chapter 1: Services at Court 4 Service Arrangements – Brief Description 4 Arbroath Sheriff Court 4 Glasgow Sheriff Court 5 Hamilton Sheriff Court 7 Dumbarton Sheriff Court 8 Chapter 2: Key Themes 9 Post- Sentence Interviews 10 Serving Prisoners 12 Suggestions 13 Priorities 13 Views of Staff in Prisons 14 Interviewing offenders at court after they have been sentenced to a community disposal 15 Quality Assurance 16 Purpose and Role of Social Work Services at Court 18 Appropriate Skill-Mix for Staff 21 Information Transmission at Court 22 District Courts 24 Chapter 3: Conclusions and Recommendations 26 Annexes 1. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-16336-2 — Medieval Historical Writing Edited by Jennifer Jahner , Emily Steiner , Elizabeth M

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-16336-2 — Medieval Historical Writing Edited by Jennifer Jahner , Emily Steiner , Elizabeth M. Tyler Index More Information Index 1381 Rising. See Peasants’ Revolt Alcuin, 123, 159, 171 Alexander Minorita of Bremen, 66 Abbo of Fleury, 169 Alexander the Great (Alexander III), 123–4, Abbreviatio chronicarum (Matthew Paris), 230, 233 319, 324 Alfred of Beverley, Annales, 72, 73, 78 Abbreviationes chronicarum (Ralph de Alfred the Great, 105, 114, 151, 155, 159–60, 162–3, Diceto), 325 167, 171, 173, 174, 175, 176–7, 183, 190, 244, Abelard. See Peter Abelard 256, 307 Abingdon Apocalypse, 58 Allan, Alison, 98–9 Adam of Usk, 465, 467 Allen, Michael I., 56 Adam the Cellarer, 49 Alnwick, William, 205 Adomnán, Life of Columba, 301–2, 422 ‘Altitonantis’, 407–9 Ælfflæd, abbess of Whitby, 305 Ambrosius Aurelianus, 28, 33 Ælfric of Eynsham, 48, 152, 171, 180, 306, 423, Amis and Amiloun, 398 425, 426 Amphibalus, Saint, 325, 330 De oratione Moysi, 161 Amra Choluim Chille (Eulogy of St Lives of the Saints, 423 Columba), 287 Aelred of Rievaulx, 42–3, 47 An Dubhaltach Óg Mac Fhirbhisigh (Dudly De genealogia regum Anglorum, 325 Ferbisie or McCryushy), 291 Mirror of Charity, 42–3 anachronism, 418–19 Spiritual Friendship, 43 ancestral romances, 390, 391, 398 Aeneid (Virgil), 122 Andreas, 425 Æthelbald, 175, 178, 413 Andrew of Wyntoun, 230, 232, 237 Æthelred, 160, 163, 173, 182, 307, 311 Angevin England, 94, 390, 391, 392, 393 Æthelstan, 114, 148–9, 152, 162 Angles, 32, 103–4, 146, 304–5, 308, 315–16 Æthelthryth (Etheldrede), -

THE MYTHOLOGY, TRADITIONS and HISTORY of Macdhubhsith

THE MYTHOLOGY, TRADITIONS and HISTORY OF MacDHUBHSITH ― MacDUFFIE CLAN (McAfie, McDuffie, MacFie, MacPhee, Duffy, etc.) VOLUME 2 THE LANDS OF OUR FATHERS PART 2 Earle Douglas MacPhee (1894 - 1982) M.M., M.A., M.Educ., LL.D., D.U.C., D.C.L. Emeritus Dean University of British Columbia This 2009 electronic edition Volume 2 is a scan of the 1975 Volume VII. Dr. MacPhee created Volume VII when he added supplemental data and errata to the original 1792 Volume II. This electronic edition has been amended for the errata noted by Dr. MacPhee. - i - THE LIVES OF OUR FATHERS PREFACE TO VOLUME II In Volume I the author has established the surnames of most of our Clan and has proposed the sources of the peculiar name by which our Gaelic compatriots defined us. In this examination we have examined alternate progenitors of the family. Any reader of Scottish history realizes that Highlanders like to move and like to set up small groups of people in which they can become heads of families or chieftains. This was true in Colonsay and there were almost a dozen areas in Scotland where the clansman and his children regard one of these as 'home'. The writer has tried to define the nature of these homes, and to study their growth. It will take some years to organize comparative material and we have indicated in Chapter III the areas which should require research. In Chapter IV the writer has prepared a list of possible chiefs of the clan over a thousand years. The books on our Clan give very little information on these chiefs but the writer has recorded some probable comments on his chiefship. -

ROBERT GERAINT GRUFFYDD Robert Geraint Gruffydd 1928–2015

ROBERT GERAINT GRUFFYDD Robert Geraint Gruffydd 1928–2015 GERAINT GRUFFYDD RESEARCHED IN EVERY PERIOD—the whole gamut—of Welsh literature, and he published important contributions on its com- plete panorama from the sixth to the twentieth century. He himself spe- cialised in two periods in particular—the medieval ‘Poets of the Princes’ and the Renaissance. But in tandem with that concentration, he was renowned for his unique mastery of detail in all other parts of the spec- trum. This, for many acquainted with his work, was his paramount excel- lence, and reflected the uniqueness of his career. Geraint Gruffydd was born on 9 June 1928 on a farm named Egryn in Tal-y-bont, Meirionnydd, the second child of Moses and Ceridwen Griffith. According to Peter Smith’sHouses of the Welsh Countryside (London, 1975), Egryn dated back to the fifteenth century. But its founda- tions were dated in David Williams’s Atlas of Cistercian Lands in Wales (Cardiff, 1990) as early as 1391. In the eighteenth century, the house had been something of a centre of culture in Meirionnydd where ‘the sound of harp music and interludes were played’, with ‘the drinking of mead and the singing of ancient song’, according to the scholar William Owen-Pughe who lived there. Owen- Pughe’s name in his time was among the most famous in Welsh culture. An important lexicographer, his dictionary left its influence heavily, even notoriously, on the development of nineteenth-century literature. And it is strangely coincidental that in the twentieth century, in his home, was born and bred for a while a major Welsh literary scholar, superior to him by far in his achievement, who too, for his first professional activity, had started his career as a lexicographer. -

A Very Rough Guide to the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of The

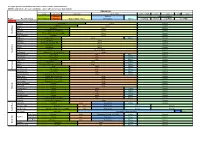

A Very Rough Guide To the Main DNA Sources of the Counties of the British Isles (NB This only includes the major contributors - others will have had more limited input) TIMELINE (AD) ? - 43 43 - c410 c410 - 878 c878 - 1066 1066 -> c1086 1169 1283 -> c1289 1290 (limited) (limited) Normans (limited) Region Pre 1974 County Ancient Britons Romans Angles / Saxon / Jutes Norwegians Danes conq Engl inv Irel conq Wales Isle of Man ENGLAND Cornwall Dumnonii Saxon Norman Devon Dumnonii Saxon Norman Dorset Durotriges Saxon Norman Somerset Durotriges (S), Belgae (N) Saxon Norman South West South Wiltshire Belgae (S&W), Atrebates (N&E) Saxon Norman Gloucestershire Dobunni Saxon Norman Middlesex Catuvellauni Saxon Danes Norman Berkshire Atrebates Saxon Norman Hampshire Belgae (S), Atrebates (N) Saxon Norman Surrey Regnenses Saxon Norman Sussex Regnenses Saxon Norman Kent Canti Jute then Saxon Norman South East South Oxfordshire Dobunni (W), Catuvellauni (E) Angle Norman Buckinghamshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Bedfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Hertfordshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Essex Trinovantes Saxon Danes Norman Suffolk Trinovantes (S & mid), Iceni (N) Angle Danes Norman Norfolk Iceni Angle Danes Norman East Anglia East Cambridgeshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Huntingdonshire Catuvellauni Angle Danes Norman Northamptonshire Catuvellauni (S), Coritani (N) Angle Danes Norman Warwickshire Coritani (E), Cornovii (W) Angle Norman Worcestershire Dobunni (S), Cornovii (N) Angle Norman Herefordshire Dobunni (S), Cornovii -

Whyte, Alasdair C. (2017) Settlement-Names and Society: Analysis of the Medieval Districts of Forsa and Moloros in the Parish of Torosay, Mull

Whyte, Alasdair C. (2017) Settlement-names and society: analysis of the medieval districts of Forsa and Moloros in the parish of Torosay, Mull. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/8224/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten:Theses http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Settlement-Names and Society: analysis of the medieval districts of Forsa and Moloros in the parish of Torosay, Mull. Alasdair C. Whyte MA MRes Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Celtic and Gaelic | Ceiltis is Gàidhlig School of Humanities | Sgoil nan Daonnachdan College of Arts | Colaiste nan Ealain University of Glasgow | Oilthigh Ghlaschu May 2017 © Alasdair C. Whyte 2017 2 ABSTRACT This is a study of settlement and society in the parish of Torosay on the Inner Hebridean island of Mull, through the earliest known settlement-names of two of its medieval districts: Forsa and Moloros.1 The earliest settlement-names, 35 in total, were coined in two languages: Gaelic and Old Norse (hereafter abbreviated to ON) (see Abbreviations, below). -

The Great Migration: DNA Testing Companies Allow Us to Answer The

We Scots Are All Immigrants – And Cousins to Boot! by John King Bellassai * [This article appears in abbreviated form in the current issue of Scots Heritage Magazine. It is reprinted here in its entirety with the permission of the editors of that publication.] America is a nation of immigrants. In fact, North America was uninhabited until incomers from Asia crossed a land bridge from Siberia to Alaska some 12,000 years ago—right after the last Ice Age—to eventually spread across the continent. In addition, recent evidence suggests that at about the same time, other incomers arrived in South America by boat from Polynesia and points in Southeast Asia, spreading up the west coast of the contingent. Which means the ancestors of everyone here in the Americas, everyone who has ever been here, came from somewhere else. Less well known is the fact that Britain, too, has been from the start a land of immigrants. In recent years geology, climatology, paleo-archaeology, and genetic population research have come together to demonstrate the hidden history of prehistoric Britain—something far different than what was traditionally believed and taught in schools. We now know that no peoples were indigenous to Britain. True, traces of humanoids there go back 800,000 years (the so-called Happisburg footprints), and modern humans (Cro-Magnon Man) did indeed inhabit Britain about 40,000 years ago. But we also now know that no one alive today in Britain descends from these people. Rather, during the last Ice Age, Britain, like the rest of Northern Europe, was uninhabited—and uninhabitable. -

Viking Wirral … and the Battle of Brunanburh Professor Steve Harding

Viking Wirral … and the Battle of Brunanburh Professor Steve Harding Neil Oliver, “History of Scotland” BBC2, 2009 “ The many armies, tens of thousands of warriors clashed at the site known as Brunanburh where the Mersey Estuary enters the sea . For decades afterwards it was simply known called the Great Battle. This was the mother of all dark-age bloodbaths and would define the shape of Britain into the modern era. Althouggg,h Athelstan emerged victorious, the resistance of the northern alliance had put an end to his dream of conquering the whole of Britain. This had been a battle for Britain, one of the most important battles in British historyyy and yet today ypp few people have even heard of it. 937 doesn’t quite have the ring of 1066 and yet Brunanburh was about much more than blood and conquest. This was a showdown between two very different ethnic identities – a Norse-Celtic alliance versus Anglo-Saxon. It aimed to settle once and for all whether Britain would be controlled by a single Imperial power or remain several separate kingdoms. A split in perceptions which, like it or not, is still with us today”. Some of the people who’ve been trying to sort it out Nic k Hig ham Pau l Cav ill Mic hae l Woo d John McNeal Dodgson 1928-1990 Plan •Background of Brunanburh • Evidence for Wirral location for the battle • If it did happen in Wirra l, w here is a like ly site for the battle • Consequences of the Battle for Wirral – and Britain Background of Brunanburh “Cherchez la Femme!” Ann Anderson (1964) The Story of Bromborough •TheThe Viking -

Headquarters, Strathclyde Regional Council, 20 India Street, Glasgow

312 THE EDINBURGH GAZETTE 3 MARCH 1987 NOTICE OF SUBMISSION OF ALTERATIONS Kyle & Carrick District Council, Headquarters, TO STRUCTURE PLAN Clydesdale District Council, Burns House, Headquarters, TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING (SCOTLAND) ACT 1972 Burns Statue Square, Council Offices, Ayr STRATHCLYDE STRUCTURE PLAN South Vennel, Lanark Monklands District Council, THE Strathclyde Regional Council submitted alterations to the above- Headquarters, named structure plan to the Secretary of State for Scotland on 18th Cumbernauld & Kilsyth District Municipal Buildings, February 1987 for his approval. Council, Coatbridge Headquarters, Certified copies of the alterations to the plan, of the report of the Council Offices, results of review of relevant matters and of the statement mentioned in Motherwell District Council, Bron Way, Section 8(4) of the Act have been deposited at the offices specified on the Headquarters, Cumbernauld Schedule hereto. Civic Centre, Motherwell The deposited documents are available for inspection free of charge Cumnock & Doon Valley District during normal office hours. Council, Renfrew District Council, Objections to the alterations to the structure plan should be sent in Headquarters, Headquarters, writing to the Secretary, Scottish Development Department, New St Council Offices, Municipal Buildings, Andrew's House, St James Centre, Edinburgh EH1 3SZ, before 6th Lugar, Cotton Street, April 1987. Objections should state the name and address of the Cumnock Paisley objector, the matters to which they relate, and the grounds on which they are made*. A person making objections may request to be notified Strathkelvin District Council, of the decision on the alterations to the plan. Headquarters, Council Chambers, * Forms for making objections are available at the places where Tom Johnston House, documents have been deposited. -

Ireland and Scotland in the Later Middle Ages»

ANALES DE LA UNIVERSIDAD DE ALICANTE. HISTORIA MEDIEVAL, n.º 19 (2015-2016): 153-174 DOI:10.14198/medieval.2015-2016.19.05 I.S.S.N.: 0212-2480 Puede citar este artículo como: Brown, Michael. «Realms, regions and lords: Ireland and Scotland in the later Middle Ages». Anales de la Universidad de Alicante. Historia Medieval, N. 19 (2015-2016): 153-174, DOI:10.14198/ medieval.2015-2016.19.05 REALMS, REGIONS AND LORDS: IRELAND AND SCOTLAND IN THE LATER MIDDLE AGES Michael Brown Department of Scottish History, University of St Andrews RESUMEN Los estudios sobre política de las Islas Británicas en la baja edad media han tendido a tratar sobre territorios concretos o a poner el Reino de Inglaterra en el centro de los debates. No obstante, en términos de su tamaño y carácter interno, hay buenas razones para considerar el Reino de Escocia y el Señorío de Irlanda como modelos de sociedad política. Más allá las significativas diferencias en el estatus, leyes y relaciones externas, hacia el año 1400 los dos territorios pueden relacionarse por compartir experiencias comunes de gobierno y de guerras internas. Éstas son las más aparentes desde una perspectiva regional. Tanto Irlanda y Escocia operaban como sistemas políticos regionalizados en los que predominaban los intereses de las principales casas aristocráticas. La importancia de dichas casas fue reconocida tanto internamente como por el gobierno real. Observando en regiones paralelas, Munster y el nordeste de Escocia, es posible identificar rasgos comparables y diferencias de largo término en dichas sociedades. Palabras clave: Baja edad media; Escocia; Irlanda; Guerra; Gobierno. -

International Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol

International Journal of Language and Linguistics Vol. 7, No. 3, September 2020 doi:10.30845/ijll.v7n3p2 Skaldic Panegyric and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Poem on the Redemption of the Five Boroughs Leading Researcher Inna Matyushina Russian State University for the Humanities Miusskaya Ploshchad korpus 6, Moscow Russia, 125047 Honorary Professor, University of Exeter Queen's Building, The Queen's Drive Streatham Campus, Exeter, EX4 4QJ Summary: The paper attempts to reveal the affinities between skaldic panegyric poetry and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle poem on the ‘Redemption of the Five Boroughs’ included into four manuscripts (Parker, Worcester and both Abingdon) for the year 942. The thirteen lines of the Chronicle poem are laden with toponyms and ethnonyms, prompting scholars to suggest that its main function is mnemonic. However comparison with skaldic drápur points to the communicative aim of the lists of toponyms and ethnonyms, whose function is to mark the restoration of the space defining the historical significance of Edmund’s victory. The Chronicle poem unites the motifs of glory, spatial conquest and protection of land which are also present in Sighvat’s Knútsdrápa (SkP I 660. 9. 1-8), bearing thematic, situational, structural and functional affinity with the former. Like that of Knútsdrápa, the function of the Chronicle poem is to glorify the ruler by formally reconstructing space. The poem, which, unlike most Anglo-Saxon poetry, is centred not on a past but on a contemporary event, is encomium regis, traditional for skaldic poetry. ‘The Redemption of the Five Boroughs’ can be called an Anglo-Saxon equivalent of erfidrápa, directed to posterity and ensuring eternal fame for the ruler who reconstructed the spatial identity of his kingdom.