Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi………………………………………

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Widsith Beowulf. Beowulf Beowulf

CHAPTER 1 OLD ENGLISH LITERATURE The Old English language or Anglo-Saxon is the earliest form of English. The period is a long one and it is generally considered that Old English was spoken from about A.D. 600 to about 1100. Many of the poems of the period are pagan, in particular Widsith and Beowulf. The greatest English poem, Beowulf is the first English epic. The author of Beowulf is anonymous. It is a story of a brave young man Beowulf in 3182 lines. In this epic poem, Beowulf sails to Denmark with a band of warriors to save the King of Denmark, Hrothgar. Beowulf saves Danish King Hrothgar from a terrible monster called Grendel. The mother of Grendel who sought vengeance for the death of her son was also killed by Beowulf. Beowulf was rewarded and became King. After a prosperous reign of some forty years, Beowulf slays a dragon but in the fight he himself receives a mortal wound and dies. The poem concludes with the funeral ceremonies in honour of the dead hero. Though the poem Beowulf is little interesting to contemporary readers, it is a very important poem in the Old English period because it gives an interesting picture of the life and practices of old days. The difficulty encountered in reading Old English Literature lies in the fact that the language is very different from that of today. There was no rhyme in Old English poems. Instead they used alliteration. Besides Beowulf, there are many other Old English poems. Widsith, Genesis A, Genesis B, Exodus, The Wanderer, The Seafarer, Wife’s Lament, Husband’s Message, Christ and Satan, Daniel, Andreas, Guthlac, The Dream of the Rood, The Battle of Maldon etc. -

1.1 Biblical Wisdom

JOB, ECCLESIASTES, AND THE MECHANICS OF WISDOM IN OLD ENGLISH POETRY by KARL ARTHUR ERIK PERSSON B. A., Hon., The University of Regina, 2005 M. A., The University of Regina, 2007 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (English) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) February 2014 © Karl Arthur Erik Persson, 2014 Abstract This dissertation raises and answers, as far as possible within its scope, the following question: “What does Old English wisdom literature have to do with Biblical wisdom literature?” Critics have analyzed Old English wisdom with regard to a variety of analogous wisdom cultures; Carolyne Larrington (A Store of Common Sense) studies Old Norse analogues, Susan Deskis (Beowulf and the Medieval Proverb Tradition) situates Beowulf’s wisdom in relation to broader medieval proverb culture, and Charles Dunn and Morton Bloomfield (The Role of the Poet in Early Societies) situate Old English wisdom amidst a variety of international wisdom writings. But though Biblical wisdom was demonstrably available to Anglo-Saxon readers, and though critics generally assume certain parallels between Old English and Biblical wisdom, none has undertaken a detailed study of these parallels or their role as a precondition for the development of the Old English wisdom tradition. Limiting itself to the discussion of two Biblical wisdom texts, Job and Ecclesiastes, this dissertation undertakes the beginnings of such a study, orienting interpretation of these books via contemporaneous reception by figures such as Gregory the Great (Moralia in Job, Werferth’s Old English translation of the Dialogues), Jerome (Commentarius in Ecclesiasten), Ælfric (“Dominica I in Mense Septembri Quando Legitur Job”), and Alcuin (Commentarius Super Ecclesiasten). -

"For the Advancement of So Good a Cause": Hugh Mackay, the Highland War and the Glorious Revolution in Scotland

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 4-2012 "For the Advancement of So Good a Cause": Hugh MacKay, the Highland War and the Glorious Revolution in Scotland Andrew Phillip Frantz College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Frantz, Andrew Phillip, ""For the Advancement of So Good a Cause": Hugh MacKay, the Highland War and the Glorious Revolution in Scotland" (2012). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 480. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/480 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF SO GOOD A CAUSE”: HUGH MACKAY, THE HIGHLAND WAR AND THE GLORIOUS REVOLUTION IN SCOTLAND A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors is History from the College of William and Mary in Virginia, by Andrew Phillip Frantz Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) _________________________________________ Nicholas Popper, Director _________________________________________ Paul Mapp _________________________________________ Simon Stow Williamsburg, Virginia April 30, 2012 Contents Figures iii Acknowledgements iv Introduction 1 Chapter I The Origins of the Conflict 13 Chapter II Hugh MacKay and the Glorious Revolution 33 Conclusion 101 Bibliography 105 iii Figures 1. General Hugh MacKay, from The Life of Lieutenant-General Hugh MacKay (1836) 41 2. The Kingdom of Scotland 65 iv Acknowledgements William of Orange would not have been able to succeed in his efforts to claim the British crowns if it were not for thousands of people across all three kingdoms, and beyond, who rallied to his cause. -

BRITISH Mingclbut and BRITISH Crvil POLICIES CTNDER the EARLY STUARTS

THE SOVEREIGN OF ALL THESE ISLES: BRITISH MINGClbUT AND BRITISH CrVIL POLICIES CTNDER THE EARLY STUARTS A Thesis Presented to The Factg of Graduate Studies of The University of Guelph by ANDREW D. NICHOLLS In partial falfilment of reqoirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Jnne, 1997 O Andrew D. Nicholls, 1997 National Library Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services seMces bibliographiques The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Lhrary of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distnibute or sell reproduire, prêter, &strri.uer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownefship of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fkom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT THE SOVEREIGN OF ALL THESE ISLES: BRITISH KINGCRAFT AND BRITISH CML POLICIES UNDER THE EARLY STUARTS Andrew D. Nichoiis Advisors: University of Guelph, 1997 Dr. J.D. Alsop Dr. Donna Andrew This thesis is concemed with the challenge of multiple rule in the British Isles and extent to which the early Stuart monarchs, James VI and 1, and Charles 1, identified issues which were common to England, Scotland, and Lreland. -

The Whigs and the Peninsular War, 1808-1814 Author(S): Godfrey Davies Source: Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, Vol

The Whigs and the Peninsular War, 1808-1814 Author(s): Godfrey Davies Source: Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, Vol. 2 (1919), pp. 113-131 Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Royal Historical Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3678254 Accessed: 27-06-2016 03:54 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Royal Historical Society, Cambridge University Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Transactions of the Royal Historical Society This content downloaded from 128.197.26.12 on Mon, 27 Jun 2016 03:54:42 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms THE WHIGS AND THE PENINSULAR WAR, i808-1814 BY GODFREY DAVIES, M.A., F.R.HIST.S. Read March 13, 1919 THE attempt of George III to revive personal govern- ment tended to embitter politics and to accentuate the differences between the two rival parties in the State. At the same time the distrust existing between the various sections of the Whigs proved that personal animosities were unusually prominent. Conciliation seemed to be regarded as a sign of weakness, and the general antipathy to compromise was strengthened by the unpopular union of Fox and North in I783. -

Redeeming Beowulf and Byrhtnoth

Redeeming Beowulf: The Heroic Idiom as Marker of Quality in Old English Poetry Abstract: Although it has been fashionable lately to read Old English poetry as being critical of the values of heroic culture, the heroic idiom is the main, and perhaps the only, marker of quality in Old English poetry. Considering in turn the ‘sacred heroic’ in Genesis A and Andreas, the ‘mock heroic’ in Judith and Riddle 51, and the fiercely debated status of Byrhtnoth and Beowulf in The Battle of Maldon and Beowulf, this discussion suggests that modern scholarship has confused the measure with the measured. Although an uncritical heroic idiom may not be to modern critical tastes, it is suggested here that the variety of ways in which the heroic idiom is used to evaluate and mark value demonstrates the flexibility and depth of insight achieved by Old English poets through their apparently limited subject matter. A hero can only be defined by a narrative in which he or she meets or exceeds measures set by society—in which he or she demonstrates his or her quality. In that sense, all heroic narratives are narratives about quality. In Old English poetry, the heroic idiom stands as the marker of quality for a wide range of things: people, artefacts, actions, and events that are good, respected, desirable, and valued are marked by being presented with the characteristic language and ethic of an idealised, archaic warrior-culture.1 This is not, of course, a new point; it is traditional in Old English scholarship to associate quality with the elite, military world of generous war-lords, loyal thegns, gorgeous equipment, great acts of courage, and 1 The characteristic subject matter and style of Old English poetry is referred to in varying ways by critics. -

University of California, Los Angeles Invisible Labor In

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, LOS ANGELES INVISIBLE LABOR IN THE MEDIEVAL WORLD A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS BY ANGIE RODRGUEZ ADVISOR: MATTHEW FISHER LOS ANGELES, CA MARCH 11, 2020 ABSTRACT INVISIBLE LABOR IN THE MEDIEVAL WORLD BY ANGIE RODRIGUEZ This thesis explores invisible labor, which is a conteMporary term, as written in Old English literature. This thesis contends that invisible labor refers to labor that is ignored, underpaid, oftentiMes spans across social hierarchies and is socially constructed. The first part of this thesis goes into the conteMporary understanding of invisible labor, how this understanding leads to recognition of invisible labor in Old English literature and shows that this labor is not gender specific. The second part of this thesis goes into peace-weaving as invisible labor, which had been culturally considered women’s work and economically devalued, as depicted by the actions of Wealhtheow when she serves mead and speaks up for her sons in Beowulf and heroic actions of killing Holofernes by Judith in Judith. The third part of this thesis explores peaceMaker as invisible labor, as depicted by Wiglaf serving “water” in Beowulf, Widsith taking Ealhhild to her new king in Widsith, Constantine taking advice from the Angel as depicted in Cynewulf’s Elene, the soldiers standing by King Athelstan and defeating the Scots in “The Battle of Brunburgh,” and the men being faithful to AEthelred against the Vikings in “The Battle of Maldon.” In analyzing invisible labor as depicted in Old English literature, what may be viewed in conteMporary terms as “ordinary” work of service that is easily disMissed and unrecognized, will bring insight into how invisible labor was seen in Old English literature. -

The English Civil Wars a Beginner’S Guide

The English Civil Wars A Beginner’s Guide Patrick Little A Oneworld Paperback Original Published in North America, Great Britain and Australia by Oneworld Publications, 2014 Copyright © Patrick Little 2014 The moral right of Patrick Little to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by him/her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 All rights reserved Copyright under Berne Convention A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library ISBN 9781780743318 eISBN 9781780743325 Typeset by Siliconchips Services Ltd, UK Printed and bound in Denmark by Nørhaven A/S Oneworld Publications 10 Bloomsbury Street London WC1B 3SR England Stay up to date with the latest books, special offers, and exclusive content from Oneworld with our monthly newsletter Sign up on our website www.oneworld-publications.com Contents Preface vii Map of the English Civil Wars, 1642–51 ix 1 The outbreak of war 1 2 ‘This war without an enemy’: the first civil war, 1642–6 17 3 The search for settlement, 1646–9 34 4 The commonwealth, 1649–51 48 5 The armies 66 6 The generals 82 7 Politics 98 8 Religion 113 9 War and society 126 10 Legacy 141 Timeline 150 Further reading 153 Index 157 Preface In writing this book, I had two primary aims. The first was to produce a concise, accessible account of the conflicts collectively known as the English Civil Wars. The second was to try to give the reader some idea of what it was like to live through that trau- matic episode. -

Affective Criticism, Oral Poetics, and Beowulf's Fight with the Dragon

Oral Tradition, 10/1 (1995): 54-90 Affective Criticism, Oral Poetics, and Beowulf’s Fight with the Dragon Mark C. Amodio I Affective criticism, as it has been practiced over the last few years, has come to focus upon the reader’s (or audience’s) subjective experience of a given literary work.1 Rather than examining the text qua object, affective criticism (like all subjective criticism) has abandoned the objectivism and textual reification which lay at the heart of the New Critical enterprise, striving instead to lead “one away from the ‘thing itself’ in all its solidity to the inchoate impressions of a variable and various reader” (Fish 1980:42).2 Shifting the critical focus away from the text to the reader has engendered 1 Iser, one of the leading proponents of reader-based inquiry, offers the following succinct statement of the logic underlying his and related approaches: “[a]s a literary text can only produce a response when it is read, it is virtually impossible to describe this response without also analyzing the reading process” (1978:ix). Iser’s emphasis on the reader’s role and on the constitutive and enabling functions inherent in the act of reading are shared by many other modern theorists despite their radical differences in methodologies, aims, and conclusions. See especially Culler (1982:17-83), and the collections edited by Tompkins (1980) and Suleiman and Crosman (1980). 2 The New Criticism has generally warned against inscribing an idiosyncratic, historically and culturally determined reader into a literary text because doing so would lead to subjectivism and ultimately to interpretative chaos. -

English Legal History Mon., 13 Sep

Outline--English Legal History Mon., 13 Sep. Page 1 ANGLO-SAXON CONSTITUTIONAL HISTORY IN BRIEF SOURCES 1. Narrative history: Bede, Ecclesiastical History of the English People (Bede died 735); the Anglo- Saxon Chronicle (late 9th to mid-12th centuries); Gildas, On the Downfall and Conquest of Britain (1st half of 6th century). 2. The so-called “law codes,” beginning with Æthelberht (c. 600) and going right up through Cnut (d. 1035). 3. Language and literature: Beowulf, lyric poetry, translations of pieces of the Bible, sermons, saints’ lives, medical treatises, riddles, prayers 4. Place-names; geographical features 5. Coins 6. Art and archaeology 7. Charters BASIC CHRONOLOGY 1. The main chronological periods (Mats. p. II–1): ?450–600 — The invasions to Æthelberht of Kent Outline--English Legal History Mon., 13 Sep. Page 2 600–835 — (A healthy chunk of time here; the same amount of time that the United States has been in existence.) The period of the Heptarchy—overlordships moving from Northumbria to Mercia to Wessex. 835–924 — The Danish Invasions. 924–1066 — The kingdom of England ending with the Norman Conquest. 2. The period of the invasions (Bede on the origins of the English settlers) (Mats. p. II–1), 450–600 They came from three very powerful nations of the Germans, namely the Saxons, the Angles and the Jutes. From the stock of the Jutes are the people of Kent and the people of Wight, that is, the race which holds the Isle of Wight, and that which in the province of the West Saxons is to this day called the nation of the Jutes, situated opposite that same Isle of Wight. -

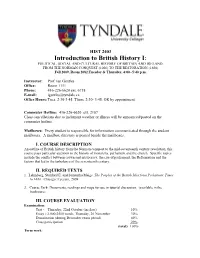

Introduction to British History I

HIST 2403 Introduction to British History I: POLITICAL, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL HISTORY OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND, FROM THE NORMAN CONQUEST (1066) TO THE RESTORATION (1660) Fall 2009, Room 2082,Tuesday & Thursday, 4:00--5:40 p.m. Instructor: Prof. Ian Gentles Office: Room 1111 Phone: 416-226-6620 ext. 6718 E-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Tues. 2:30-3:45, Thurs. 2:30- 3:45, OR by appointment Commuter Hotline: 416-226-6620 ext. 2187 Class cancellations due to inclement weather or illness will be announced/posted on the commuter hotline. Mailboxes: Every student is responsible for information communicated through the student mailboxes. A mailbox directory is posted beside the mailboxes. I. COURSE DESCRIPTION An outline of British history from the Norman conquest to the mid-seventeenth century revolution, this course pays particular attention to the history of monarchy, parliament and the church. Specific topics include the conflict between crown and aristocracy, the rise of parliament, the Reformation and the factors that led to the turbulence of the seventeenth century. II. REQUIRED TEXTS 1. Lehmberg, Stanford E. and Samantha Meigs. The Peoples of the British Isles from Prehistoric Times to 1688 . Chicago: Lyceum, 2009 2. Course Pack: Documents, readings and maps for use in tutorial discussion. (available in the bookstore) III. COURSE EVALUATION Examination : Test - Thursday, 22nd October (in class) 10% Essay - 2,000-2500 words, Thursday, 26 November 30% Examination (during December exam period) 40% Class participation 20% (total) 100% Term work : a. You are expected to attend the tutorials, preparing for them through the lectures and through assigned reading. -

Thevikingblitzkriegad789-1098.Pdf

2 In memory of Jeffrey Martin Whittock (1927–2013), much-loved and respected father and papa. 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A number of people provided valuable advice which assisted in the preparation of this book; without them, of course, carrying any responsibility for the interpretations offered by the book. We are particularly indebted to our agent Robert Dudley who, as always, offered guidance and support, as did Simon Hamlet and Mark Beynon at The History Press. In addition, Bradford-on-Avon library, and the Wiltshire and the Somerset Library services, provided access to resources through the inter-library loans service. For their help and for this service we are very grateful. Through Hannah’s undergraduate BA studies and then MPhil studies in the department of Anglo-Saxon, Norse and Celtic (ASNC) at Cambridge University (2008–12), the invaluable input of many brilliant academics has shaped our understanding of this exciting and complex period of history, and its challenging sources of evidence. The resulting familiarity with Old English, Old Norse and Insular Latin has greatly assisted in critical reflection on the written sources. As always, the support and interest provided by close family and friends cannot be measured but is much appreciated. And they have been patient as meal-time conversations have given way to discussions of the achievements of Alfred and Athelstan, the impact of Eric Bloodaxe and the agendas of the compilers of the 4 Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. 5 CONTENTS Title Dedication Acknowledgements Introduction 1 The Gathering