Fields of Wonder: Exploring the Langston Hughes Song Cycles of Robert Owens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poems for Secondary Schools

Poems for secondary schools I will rise (tribute to Maya Angelou)* by Hani Abdile Hani came to Australia from Somalia via Kenya, Malaysia, Indonesia and Christmas Island about 2013. The Somalian civil war had made her family nomadic, and she was in the greatest danger of all, aged just 17, of forced marriage among other things. Her family sent her to Australia for her own safety. She has also published a book of the same title and her facebook page has more poetry and information. Her own website https://abdilehani.wordpress.com has more information on Hani’s life, hope and activities as well as her writings. * Maya Angleou was an African American woman who wrote many books and poetry, one of the latter being Still I Rise. You now lock me in detention but one day I will rise and damage my hopes I may have bad memories but it's like dust rooted in pain and one day I will rise. but one day I will rise You may avoid my sadness I may have left a fearful life of horror and send me to Manus but one day I will rise but one day I will rise. Does my mind upset you You may hide the reality so full of thoughts? and break my heart I am an asylum seeker but one day I will rise. who seeks for freedom and don't You may send me to somewhere else. have anywhere else to go. why can’t you help me? Does it come as a surprise to you I may be female of under age that whatever you have done to me who needs assistance from you. -

President's Welcome

PRESIDENT’S WELCOME Friends, Colleagues, and Students, Welcome to the 82nd Annual Mississippi Bandmasters Association State Band Clinic in Natchez. The other members of the MBA Executive Board and I hope that you will experience growth, new perspectives, and renewed aspirations for teaching and learning music in your community during this year’s clinic. I would like to wish all of the students in attendance a heartfelt congratulations on participating in this esteemed event. You represent the very best of the students from your band programs – I encourage you to take that sentiment to heart. Thousands of students have shared in this honor for the last 82 years. Many of you will meet friends this weekend that you will have throughout your life. Lastly, I encourage you to take this opportunity to enjoy making music with others and learning from some of the most outstanding teachers in our country. For members of our association, take the time to visit with the exhibitors and clinicians throughout the weekend. Take advantage of the clinics and presentations that are offered so that you may leave Natchez with new insights and perspectives that you can use with your students at home. Clinic is also a time to renew old friendships and foster new ones. I hope that veteran teachers will take the time to get to know those that are new to our profession and new teachers will seek out the guidance of those with more experience. To our guest clinicians, exhibitors, featured ensembles, and conductors we welcome you and hope that you will enjoy your time with us. -

Paul Clarke Song List

Paul Clarke Song List Busby Marou – Biding my time Foster the People – Pumped up Kicks Boy & Bear – Blood to gold Kings of Leon – Sex on Fire, Radioactive, The Bucket The Wombats – Tokyo (vampires & werewolves) Foo Fighters – Times like these, All my life, Big Me, Learn to fly, See you Pete Murray – Class A, Better Days, So beautiful, Opportunity La Roux – Bulletproof John Butler Trio – Betterman, Better than Mark Ronson – Somebody to Love Me Empire of the Sun – We are the People Powderfinger – Sunsets, Burn your name, My Happiness Mumford and Sons – Little Lion man Hungry Kids of Hungary Scattered Diamonds SIA – Clap your hands Art Vs Science – Friend in the field Jack Johnson – Flake, Taylor, Wasting time Peter, Bjorn and John – Young Folks Faker – This Heart attack Bernard Fanning – Wish you well, Song Bird Jimmy Eat World – The Middle Outkast – Hey ya Neon Trees – Animal Snow Patrol – Chasing cars Coldplay – Yellow, The Scientist, Green Eyes, Warning Sign, The hardest part Amy Winehouse – Rehab John Mayer – Your body is a wonderland, Wheel Red Hot Chilli Peppers – Zephyr, Dani California, Universally Speaking, Soul to squeeze, Desecration song, Breaking the Girl, Under the bridge Ben Harper – Steal my kisses, Burn to shine, Another lonely Day, Burn one down The Killers – Smile like you mean it, Read my mind Dane Rumble – Always be there Eskimo Joe – Don’t let me down, From the Sea, New York, Sarah Aloe Blacc – Need a dollar Angus & Julia Stone – Mango Tree, Big Jet Plane Bob Evans – Don’t you think -

![Short Stories]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3643/short-stories-93643.webp)

Short Stories]

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1999 Riparia| [Short stories] Danis Banks The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Banks, Danis, "Riparia| [Short stories]" (1999). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 3447. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/3447 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. M I llMliw Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of MONTANA Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. ** Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature ** Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission /<? ^ Author's Signature. Date (7, Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. RIPARIA by Danis Banks B.A. Brown University, 1993 presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts The University of Montana 1999 Approved by: Chairperson Dean, Graduate School S-l 7-<7? Date UMI Number: EP34091 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. -

Vanguard Jazz Orchestra Plans May Tribute to Thad Jones and Mel Lewis

JazzWeek with airplay data powered by jazzweek.com • March 30, 2005 Volume 1, Number 19 • $7.95 In This Issue: Mack Avenue to Sponsor Detroit Jazz Fest. 4 WGBH Ups Rivero to Radio/ TV GM . 5 Camilo Embarks . 6 441 Launches Test of Time . 9 Reviews and Picks. 15 Jazz Radio . 18 Smooth Jazz Radio. 23 RADIO Q&A: Radio WEMU’S Panels. 27 LINDA YOHN News. 4 page 12 Charts: #1 Jazz Album – Joey DeFrancesco #1 Smooth Album – Dave Koz #1 Smooth Single – Dave Koz JazzWeek This Week EDITOR Ed Trefzger ’m thrilled that we get to feature another of our favorite people CONTRIBUTING EDITORS in jazz radio this week, WEMU music director Linda Yohn. Keith Zimmerman Kent Zimmerman ILinda is a nominee for the Jazz Journalists Association Excel- Tad Hendrickson lence in Jazz Broadcasting/Willis Conover-Marian McPartland CONTRIBUTING WRITER Award. She has been there encouraging and supporting our ef- Tom Mallison forts even before there was a JazzWeek, as one of the first par- PHOTOGRAPHY ticipants on the Jazz Programmers Mailing List. Linda has been Barry Solof a key figure at each of JazzWeek’s Summits and an active part of PUBLISHER the industry tracks at IAJE for years. As host of the 9 a.m. to noon Tony Gasparre shift on WEMU, Linda shows everyone how jazz radio should be ADVERTISING: Contact Tony Gasparre done, and thanks to the ’net, those of us outside of Ypsilanti/Ann (585) 235-4685 x3 or Arbor/Detroit get to eavesdrop. email: [email protected] While we’re talking about the Motor City, hats off to Mack SUBSCRIPTIONS: Prices in US Dollars: Avenue Records for picking up the sponsorship of the Detroit In- Charter Rate: $199.00 per year, ternational Jazz Festival. -

Hearing Nostalgia in the Twilight Zone

JPTV 6 (1) pp. 59–80 Intellect Limited 2018 Journal of Popular Television Volume 6 Number 1 © 2018 Intellect Ltd Article. English language. doi: 10.1386/jptv.6.1.59_1 Reba A. Wissner Montclair State University No time like the past: Hearing nostalgia in The Twilight Zone Abstract Keywords One of Rod Serling’s favourite topics of exploration in The Twilight Zone (1959–64) Twilight Zone is nostalgia, which pervaded many of the episodes of the series. Although Serling Rod Serling himself often looked back upon the past wishing to regain it, he did, however, under- nostalgia stand that we often see things looking back that were not there and that the past is CBS often idealized. Like Serling, many ageing characters in The Twilight Zone often sentimentality look back or travel to the past to reclaim what they had lost. While this is a perva- stock music sive theme in the plots, in these episodes the music which accompanies the scores depict the reality of the past, showing that it is not as wonderful as the charac- ter imagined. Often, music from these various situations is reused within the same context, allowing for a stock music collection of music of nostalgia from the series. This article discusses the music of nostalgia in The Twilight Zone and the ways in which the music depicts the reality of the harshness of the past. By feeding into their own longing for the reclamation of the past, the writers and composers of these episodes remind us that what we remember is not always what was there. -

Rollbackfinaledit3.Pdf

Prologue Science fiction stories always fascinated me, especially during my teen years. For many decades, I daydreamed and fantasized about the possibilities of revisiting past times, especially those of my youth. Now on the backside of middle age, I understand that my fascination is quite common. Much discussion regarding the possibilities of time travel is regularly seen on TV science programs and related web sites. They are also themes of numerous books and movies. This leads us to the reason for this narrative. This is a story I have only shared with a trusted few. If it became common knowledge I fear I would become the subject of much unwanted scrutiny. This scrutiny might also involve more than just the idle tongue wagging of the neighborhood gossips. Certainly it wouldn’t improve my quality of life. This is something I have no desire to deal with at my age. Now the simple truth is this, I have actually been involved in time travel. This is possible because of my introduction to a time portal to a parallel dimension. It would be more accurate to say parallel dimensions, because there are many more than just the one in which we live. Chapter 1 I never dreamed I would be involved in a series of events that if known by the general public, would have landed me in one of those secret government interrogation rooms you’d read about in some thriller novel. In a period of less than four months I experienced more sensory overload than in the past sixty- five years of my life. -

RESISTANCE MADE in HOLLYWOOD: American Movies on Nazi Germany, 1939-1945

1 RESISTANCE MADE IN HOLLYWOOD: American Movies on Nazi Germany, 1939-1945 Mercer Brady Senior Honors Thesis in History University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Department of History Advisor: Prof. Karen Hagemann Co-Reader: Prof. Fitz Brundage Date: March 16, 2020 2 Acknowledgements I want to thank Dr. Karen Hagemann. I had not worked with Dr. Hagemann before this process; she took a chance on me by becoming my advisor. I thought that I would be unable to pursue an honors thesis. By being my advisor, she made this experience possible. Her interest and dedication to my work exceeded my expectations. My thesis greatly benefited from her input. Thank you, Dr. Hagemann, for your generosity with your time and genuine interest in this thesis and its success. Thank you to Dr. Fitz Brundage for his helpful comments and willingness to be my second reader. I would also like to thank Dr. Michelle King for her valuable suggestions and support throughout this process. I am very grateful for Dr. Hagemann and Dr. King. Thank you both for keeping me motivated and believing in my work. Thank you to my roommates, Julia Wunder, Waverly Leonard, and Jamie Antinori, for being so supportive. They understood when I could not be social and continued to be there for me. They saw more of the actual writing of this thesis than anyone else. Thank you for being great listeners and wonderful friends. Thank you also to my parents, Joe and Krista Brady, for their unwavering encouragement and trust in my judgment. I would also like to thank my sister, Mahlon Brady, for being willing to hear about subjects that are out of her sphere of interest. -

10CC Dreadlock Holiday 98 Degrees Because of You Aaron Neville Don

10CC My Love My Life Dreadlock Holiday One Of Us Our Last Summer 98 Degrees Rock Me Because Of You S.O.S. Slipping Through My Fingers Aaron Neville Super Trouper Don't Know Much (Duet Linda Ronstad) Take A Chance On Me For The Goodtimes Thank You For The Music The Grand Tour That's Me The Name Of The Game Aaron Tippin The Visitors Ain't Nothin' Wrong With The Radio The Winner Takes It All Kiss This Tiger Two For The Price Of One Abba Under Attack Andante, Andante Voulez Vous Angel Eyes Waterloo Another Town, Another Train When All Is Said And Done Bang A Boomerang When I Kissed The Teacher Chiquitita Why Did It Have To Be Me Dance (While The Music Still Goes On) Dancing Queen Abc Does Your Mother Know Poison Arrow Dum Dum Diddle The Look Of Love Fernando Gimme! Gimme! Gimme! (A Man After Midnight) Ac Dc Happy New Year For Those About To Rock Hasta Manana Have A Drink On Me He Is Your Brother Highway To Hell Hey Hey Helen Who Made Who Honey Honey Whole Lotta Rosie I Do, I Do, I Do You Shook Me All Night Long I Have A Dream I Let The Music Speak Ace Of Base I Wonder All That She Wants If It Wasn't For The Nights Beautiful Life I'm A Marionette Cruel Summer I've Been Waiting For You Don't Turn Around Kisses Of Fire Life Is A Flower Knowing Me Knowing You Lucky Love Lay All Your Love On Me The Sign Lovers(Live A Little Longer) Wheel Of Fortune Mamma Mia Money Money Money Ad Libs The Engelstalige Karaoke Holding de Riddim Entertainment Pagina 1 Boy From New York City Theme From Moonlighting Adele Al Jolson Don't You Remember Avalon I Set Fire -

Three Anti-Fascist Novels Written by Women in the 1930S

Narratives of collaboration and resistance: Three anti-fascist novels written by women in the 1930s RONALD PAUL University of Gothenburg Abstract Throughout the 1930s, the impact of fascism on the role of women in society and in the family was the focus of several anti-fascist novels written by women. In this article I concentrate on three of the most significant and successful of these works in order to explore the way they dramatize the relationship between collaboration with and resistance to fascism. I show how they not only viewed the reactionary transformation of the state by fascist regimes as a historic defeat for women. They also sought to depict the effect this catastrophe had on their personal lives and how they coped with its social and political challenges. I have therefore selected the following novels – Storm Jameson’s In the Second Year (1936), Murray Constantine’s (Katharine Burdekin) Swastika Night (1937) and Phyllis Bottome’s The Mortal Storm (1938), since they address the fundamentally regressive nature of fascism in different ways as well as individual struggles against it. Moreover, they remain outstanding examples of anti-fascist fiction that still resonate with us today when the world is once more faced with the rise of rightwing, populist and neofascist parties. Key words: Storm Jameson, Murray Constantine, Phyllis Bottome, 1930s, Anti-fascist novels In one of her last great polemics, Three Guineas, published in 1938, Virginia Woolf argued for a united front between the women’s movement and the anti-fascist struggle. Woolf showed that there is a natural and necessary correspondence between the continued fight for female emancipation and international resistance to the rise of fascism. -

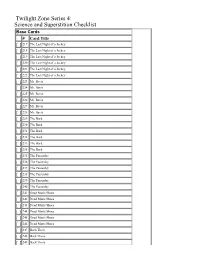

Twilight Zone Series 4: Science and Superstition Checklist

Twilight Zone Series 4: Science and Superstition Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 217 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 218 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 219 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 220 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 221 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 222 The Last Night of a Jockey [ ] 223 Mr. Bevis [ ] 224 Mr. Bevis [ ] 225 Mr. Bevis [ ] 226 Mr. Bevis [ ] 227 Mr. Bevis [ ] 228 Mr. Bevis [ ] 229 The Bard [ ] 230 The Bard [ ] 231 The Bard [ ] 232 The Bard [ ] 233 The Bard [ ] 234 The Bard [ ] 235 The Passersby [ ] 236 The Passersby [ ] 237 The Passersby [ ] 238 The Passersby [ ] 239 The Passersby [ ] 240 The Passersby [ ] 241 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 242 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 243 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 244 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 245 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 246 Dead Man's Shoes [ ] 247 Back There [ ] 248 Back There [ ] 249 Back There [ ] 250 Back There [ ] 251 Back There [ ] 252 Back There [ ] 253 The Purple Testament [ ] 254 The Purple Testament [ ] 255 The Purple Testament [ ] 256 The Purple Testament [ ] 257 The Purple Testament [ ] 258 The Purple Testament [ ] 259 A Piano in the House [ ] 260 A Piano in the House [ ] 261 A Piano in the House [ ] 262 A Piano in the House [ ] 263 A Piano in the House [ ] 264 A Piano in the House [ ] 265 Night Call [ ] 266 Night Call [ ] 267 Night Call [ ] 268 Night Call [ ] 269 Night Call [ ] 270 Night Call [ ] 271 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 272 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 273 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 274 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 275 A Hundred Yards Over the Rim [ ] 276 A Hundred -

Sorted by Title

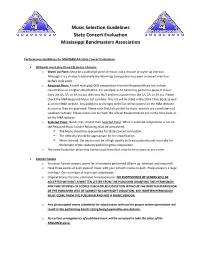

Music Selection Guidelines State Concert Evaluation Mississippi Bandmasters Association Performance Guidelines for MBA/MHSAA State Concert Evaluation • All bands must play three (3) pieces of music. o Warm Up Piece: Must be a published piece of music, not a chorale or warm up exercise. Although it is a choice, traditionally the Warm Up Composition has been a concert march or fanfare style piece. o Required Piece: A band must play ONE composition from the Required Music List in their classification or a higher classification. For example: A 4A band may perform a piece of music from the 4A, 5A, or 6A list but they may NOT perform a piece from the 1A, 2A, or 3A list. Please check the MBA Required Music List carefully. This list will be listed in the State Clinic Book as well as on the MBA website. Any additions or changes to the list will be posted on the MBA Website as soon as they are approved. Please note that lists posted by music vendors are sometimes not updated routinely. Please make sure to check the official Required Music List in the clinic book or on the MBA website. o Selected Piece: Bands may choose their Selected Piece. When a Selected composition is not on the Required Music List the following must be considered: . The Music should be appropriate for State Concert Evaluation. The difficulty should be appropriate for the classification. When learned, the music must be of high quality both educationally and musically for the benefit of the students performing the composition. o The same Evaluation piece may not be used more than once in three years at any event.