Short Stories]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesson Plans and Resources for There There by Tommy Orange

Lesson Plans and Resources for There There by Tommy Orange Table of Contents 1. Overview and Essential Questions 2. In-Class Introduction 3. Common Core Standards Alignment 4. Reader Response Questions 5. Literary Log Prompts + Worksheets 6. Suggested Analytical Assessments 7. Suggested Creative Assessments 8. Online Resources 9. Print Resources - “How to Talk to Each Other When There’s So Little Common Ground” by Tommy Orange - Book Review from The New York Times - Book Review from Tribes.org - Interview with Tommy Orange from Powell’s Book Blog These resources are all available, both separately and together, at www.freelibrary.org/onebook Please send any comments or feedback about these resources to [email protected]. OVERVIEW AND ESSENTIAL QUESTIONS The materials in this unit plan are meant to be flexible and easy to adapt to your own classroom. Each chapter has discussion questions provided in a later section. Through reading the book and completing any of the suggested activities, students can achieve any number of the following understandings: - A person’s identity does not form automatically – it must be cultivated. - Trauma is intergenerational -- hardship is often passed down through families. - A physical place can both define and destroy an individual. Students should be introduced to the following key questions as they begin reading. They can be discussed both in universal terms and in relation to specific characters in the book: Universal - How has your family cultivated your identity? How have you cultivated it yourself? -

Paul Clarke Song List

Paul Clarke Song List Busby Marou – Biding my time Foster the People – Pumped up Kicks Boy & Bear – Blood to gold Kings of Leon – Sex on Fire, Radioactive, The Bucket The Wombats – Tokyo (vampires & werewolves) Foo Fighters – Times like these, All my life, Big Me, Learn to fly, See you Pete Murray – Class A, Better Days, So beautiful, Opportunity La Roux – Bulletproof John Butler Trio – Betterman, Better than Mark Ronson – Somebody to Love Me Empire of the Sun – We are the People Powderfinger – Sunsets, Burn your name, My Happiness Mumford and Sons – Little Lion man Hungry Kids of Hungary Scattered Diamonds SIA – Clap your hands Art Vs Science – Friend in the field Jack Johnson – Flake, Taylor, Wasting time Peter, Bjorn and John – Young Folks Faker – This Heart attack Bernard Fanning – Wish you well, Song Bird Jimmy Eat World – The Middle Outkast – Hey ya Neon Trees – Animal Snow Patrol – Chasing cars Coldplay – Yellow, The Scientist, Green Eyes, Warning Sign, The hardest part Amy Winehouse – Rehab John Mayer – Your body is a wonderland, Wheel Red Hot Chilli Peppers – Zephyr, Dani California, Universally Speaking, Soul to squeeze, Desecration song, Breaking the Girl, Under the bridge Ben Harper – Steal my kisses, Burn to shine, Another lonely Day, Burn one down The Killers – Smile like you mean it, Read my mind Dane Rumble – Always be there Eskimo Joe – Don’t let me down, From the Sea, New York, Sarah Aloe Blacc – Need a dollar Angus & Julia Stone – Mango Tree, Big Jet Plane Bob Evans – Don’t you think -

ALL MY SONS a Play in Three Acts by Arthur Miller Characters: Joe Keller

ALL MY SONS a play in three acts by Arthur Miller Characters: Joe Keller (Keller) Kate Keller (Mother) Chris Keller Ann Deever George Deever Dr. Jim Bayliss (Jim) Sue Bayliss Frank Lubey Lydia Lubey Bert Act One The back yard of the Keller home in the outskirts of an American town. August of our era. The stage is hedged on right and left by tall, closely planted poplars which lend the yard a secluded atmosphere. Upstage is filled with the back of the house and its open, unroofed porch which extends into the yard some six feet. The house is two stories high and has seven rooms. It would have cost perhaps fifteen thousand in the early twenties when it was built. Now it is nicely painted, looks tight and comfortable, and the yard is green with sod, here and there plants whose season is gone. At the right, beside the house, the entrance of the driveway can be seen, but the poplars cut off view of its continuation downstage. In the left corner, downstage, stands the four‐foot‐high stump of a slender apple tree whose upper trunk and branches lie toppled beside it, fruit still clinging to its branches. Downstage right is a small, trellised arbor, shaped like a sea shell, with a decorative bulb hanging from its forward‐curving roof. Carden chairs and a table are scattered about. A garbage pail on the ground next to the porch steps, a wire leaf‐burner near it. On the rise: It is early Sunday morning. Joe Keller is sitting in the sun reading the want ads of the Sunday paper, the other sections of which lie neatly on the ground beside him. -

A Guide to the Gaps

A Guide to the Gaps By Taylor B. Ulm A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the University Honors Program University of South Florida, St. Petersburg May 5, 2016 Thesis Director: Heather Jones, M.F.A. Professor, College of Arts and Sciences University Honors Program University of South Florida St. Petersburg, Florida CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL ___________________________ Honors Thesis ___________________________ This is to certify that the Honors Thesis of Taylor B. Ulm has been approved by the Examining Committee on May 3, 2016 as satisfying the thesis requirement of the University Honors Program Examining Committee: Thesis Director: Heather Jones, M.F.A. Professor, College of Arts and Sciences Thesis Committee Member: Anda Peterson, M.F.A. Professor, College of Arts and Sciences Thesis Committee Member: Thomas Smith, Ph.D. Professor, College of Arts and Sciences A Guide to the Gaps – This book is dedicated to somebody who will probably never read it. – The Gaps Imagine this. You stand on the edge of a riverbank, And everything you’re familiar with surrounds you, The people you know, The things you hold dear. But everything is gray, Black and white is all. Your world is a colorless landscape. Now imagine you look across that river. On the other side is everything that you feel familiar with, The people you know, The things you hold dear. But is it really so familiar, If it’s all in color? That’s the only difference between this world and that. It matters not which colors you imagine, Simply imagine the colors that appeal to you. -

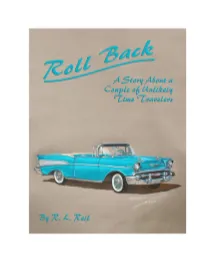

Rollbackfinaledit3.Pdf

Prologue Science fiction stories always fascinated me, especially during my teen years. For many decades, I daydreamed and fantasized about the possibilities of revisiting past times, especially those of my youth. Now on the backside of middle age, I understand that my fascination is quite common. Much discussion regarding the possibilities of time travel is regularly seen on TV science programs and related web sites. They are also themes of numerous books and movies. This leads us to the reason for this narrative. This is a story I have only shared with a trusted few. If it became common knowledge I fear I would become the subject of much unwanted scrutiny. This scrutiny might also involve more than just the idle tongue wagging of the neighborhood gossips. Certainly it wouldn’t improve my quality of life. This is something I have no desire to deal with at my age. Now the simple truth is this, I have actually been involved in time travel. This is possible because of my introduction to a time portal to a parallel dimension. It would be more accurate to say parallel dimensions, because there are many more than just the one in which we live. Chapter 1 I never dreamed I would be involved in a series of events that if known by the general public, would have landed me in one of those secret government interrogation rooms you’d read about in some thriller novel. In a period of less than four months I experienced more sensory overload than in the past sixty- five years of my life. -

CHARLIE BERENS Q GALLERY HOLIDAY FARE to Mix up Old and Manitowoc Minute Holiday Show Opens 10 Feasting Favorite PUBLISHER’S Note P

TO THE HOLIDAYS 10 WI FOODS TO FEAST UPON Get Out & Do What You Like to do NOVEMBER 2018 Christmas with the NELSONS Everyone is invited to this family CHARLIE celebration BERENS Tours WI with Manitowoc minute and More BLUES TRAVELER 30+ years and in their comfort zone UPCOMING EVENts: PLUS! Fox Cities | Green Bay TORNADO CLUB Marshfield | Oshkosh STEAK HOUSE Stevens Point | Waupaca A Madison classic Wausau | Wisconsin Rapids Marketing is essential for every business. But let’s face it, some days are a struggle to keep up with everything you are currently doing. Beyond that, in the digital age it can be downright confusing and intimidating to sort through your options. How can you keep up with the chaotic pace of doing business in an increasingly digital world? Let us help... Specializing in Contracted Digital Marketing Services Websites | eMail Marketing | Social Media | Google Business | Reputation Management www.foxxinteractiveservices.com Contact: (715) 412-1284 | [email protected] Get Out & Do What You Like to Do NOVEMBER 2018 p.22 THE NELSONS MAtthEW AND GUNNAR SHARE THEIR FAMILY CHRISTMAS WITH WIscoNSIN P. 4 P. 18 P. 28 P. 30 DEPARTMENTS BLUES TRAVELER CHARLIE BERENS Q GALLERY HOLIDAY FARE To mix up old and Manitowoc Minute Holiday Show opens 10 feasting favorite PUBLISHER’S NOTE p. 2 new in Milwaukee and beyond on in Stevens Point Wisconsin foods SUPPER CLUB p. 12 new tour Tornado Club Steak House Of Madison EVENTS CALENDAR p. 34 PUBLISHER’S NOTE NOVEMBER – A TIME FOR Family Fun Edition THANKS AND TOGETHERNESS November 2018, Vol. -

Sam Shepard's Master Class in Playwriting

Sam Shepard’s Master Class in Playwriting Brian Bartels 7 2 THE MISSOURI REVIEW / SPRING 2007 ( i n t e r v i e w ) Cherry Lane eater, in Manhattan’s West Village, is not located on Cherry Lane at all, but on Commerce Lane (nowhere near the Financial District of Lower Manhattan). It’s a venerable the- ater company that has been around for years, not very big, nowhere near Broadway, tucked in a corner on one of the most beautiful neighborhoods in New York: an urban paradise. It would seem wrong if anything other than a theater company were in this location. After everything is gone, this place feels like it will still be here, waiting for an audience. Monday, November 6, 2006, 7:46 .. Excitement hovers. e crowd is your standard theater audience: median age, late forties, and I am, as always, one of the Photograph by Joan Marcus SPRING 2007 / THE MISSOURI REVIEW 7 3 youngest people in the room. Women dominate the group: sweet, good-natured ladies who all seem to know one another. People meander inside Cherry Lane’s second-stage space, which seats about fi fty or sixty; every seat is taken. Some people are dressed like characters in one of Sam Shepard’s plays. e event is being videotaped: a surprise, given Shepard’s record of determined privacy. He doesn’t do press junkets or interviews for the fi lms he acts in. is is written into his contracts. Nor does he really like fl ying all that much. He has, however, in recent years, opened up somewhat, off ering glimpses into his artistic and personal life such as he’s generally shied away from. -

Messages of American Popular Song to Women During World War II

“I’m Doin’ It for Defense”: Messages of American Popular Song to Women during World War II A thesis submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC in the Division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music 2013 by Amy Brooks BM, Bob Jones University, 2008 Committee Chair: bruce d. mcclung, PhD Abstract World War II presented many new opportunities for American women. In this time of need, they were called upon to take an active part in the war effort, whether by means of working in a factory, growing a victory garden, or serving as a volunteer for wartime organizations. Women made great strides forward in areas such as the workforce and the military. The American popular song industry promoted these new roles for women. I have compiled over 150 songs from 1940 to1945 that relate to women’s roles during the World War II era. Of these songs, I have chosen a select number of songs that best demonstrate popular culture’s attitudes and actions towards women during the war. These songs can be divided into five categories: women in the military, women in the workforce, women’s war effort, women’s responsibilities to men in uniform, and women in the immediate post-war period. I have studied the representative songs by considering their lyrics to identify the objectives supported by the popular song industry. I took into consideration the venues in which they were presented and how these performances influenced their reception. -

{Replace with the Title of Your Dissertation}

Research Study of the Lived Experience of Alopecia Areata for Women During Early Adulthood A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Heather Bemmels IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Advisor – Pat McCarthy Veach, Ph.D. June 2017 © Heather Bemmels 2017 i Acknowledgements This author is grateful to the National Alopecia Areata Foundation, the Minnesota Alopecia Support Group, and the University of Minnesota Department of Dermatology for their assistance with recruitment. ii Abstract Objectives: Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune condition that causes baldness in men and women; however, it may be especially distressing for women given social standards and expectations for beauty. This sporadic condition can present with various extents of hair loss that unexpectedly relapse or remit across time. The present phenomenological study aimed to describe the lived experiences of early adult women with AA who developed it in pre-adolescence or adolescence, to provide greater understanding of the experience of having AA over time. Method: The present study is guided by phenomenological methods, including interpretive phenomenological analysis. Following in-depth, semi-structured interviews with six female participants ages 27-36 with current, active AA, who developed their AA between ages 10-16, data were transcribed and analyzed at an individual and general (i.e., cross case) level for themes. Results: Responses to initial awareness of AA or increasing hair loss were not uniform, with participants’ psychological experiences ranging from not being bothered to life- altering and devastating. Physical sensations and visual reminders of increased hair loss can pull participants out of their everyday experiences, with possible helplessness regarding inability to stop the loss. -

Rockland Gazette

^taxrfe anil |o ft g tin H a j. £lje lurklanfo fettle, PUBLISHED EVERY FRIDAY MORNING, BY Haring every facility, in PresseB, Type and other material, and the experience oi many years in the WORTMAN & PORTER, business, we are prepared to execute, in superior style, and with despatch, every description oi Job Office, No. 5 Custom-House Block. Work, such as Catalogues, By-Laws, Town Reports, TERMS: I f paid strictly in advance—per annum, $2,00 Ciroulars, Bill-Heads, Blanks, If payment is delayed 6 months 11 not paid till the close of the year, *.,50 CARDS, PROGRAMMES, LABELS CF No paper will be discontinued until ALL ar rearages are paid, unless at the option of the pub Hand Bill., Shoe Bill*, Paster*, h e . lishers. , , _ Particular attention paid to XT- Single copies five oents—for sale at the office and at the bookstores. sEJ All letters and communications must be ad VOL. 23. ROCKLAND, MAINE, FRIDAY, JANUARY 24, 1868. NO- 6. PRINTING IN COLORS. dressed to the Publishers. BRONZING, h e . E. E. WORTMAN, JOHN B. PORTER. Passengers in a runaway train, on a always holding on to the brass rod, and of that dear old critter, that I couldn’t prisoners were leaving for the North, devolved the reasons, which seemed to ately returned. Paul was indeed the fa ‘At last I have it! Oh, Paul, your tatal black and moonless nigbt, and with in another moment, was moving the I j^lp taking on and crying about it right on transports, it was announced that him unanswerable, in favor of such a vorite of the Fates. -

Aaliyah Abdul, Paula Ace of Base Adams, Bryan

DEBUT DATE PEAK WKS TITLE FULL ARTIST AALIYAH 0 7/2/94 10 8 1. Back & Forth Aaliyah 0 10/24/98 4 12 2. Are You That Somebody? Aaliyah 0 6/3/00 9 21 3. Try Again Aaliyah 0 6/15/02 32 5 4. More Than A Woman Aaliyah ABDUL, PAULA 0 8/31/91 17 1 1. Rush, Rush* Paula Abdul 1 8/31/91 ➊ 8 2. The Promise Of A New Day* Paula Abdul 0 11/16/91 4 9 3. Blowing Kisses In The Wind Paula Abdul 0 2/8/92 7 7 4. Vibeology Paula Abdul 0 5/9/92 7 5 5. Will You Marry Me? Paula Abdul 0 6/24/95 17 3 6. My Love Is For Real Paula Abdul 0 9/16/95 12 6 7. Crazy Cool Paula Abdul ACE OF BASE 2 11/13/93 ➊ 11 1. All That She Wants Ace Of Base 5 1/29/94 ➊ 17 2. The Sign Ace Of Base 4 5/28/94 ➊ 19 3. Don't Turn Around Ace Of Base 0 10/29/94 6 9 4. Living In Danger Ace Of Base 0 12/2/95 6 13 5. Beautiful Life Ace Of Base 0 4/13/96 13 5 6. Lucky Love Ace Of Base 0 7/18/98 7 11 7. Cruel Summer Ace Of Base ADAMS, BRYAN 1 8/31/91 ➊ 7 1. (Everything I Do) I Do It For You* Bryan Adams 0 9/28/91 5 12 2. Can't Stop This Thing We Started Bryan Adams 0 4/11/92 5 11 3. -

Katie Zaffrann Transcript

This transcript was exported on May 20, 2021 - view latest version here. Chris Velardi: Hey, it's Chris Velardi. Glad you found the 'Cuse Conversations podcast. Our guest today, Katie Zaffrann, a 2004 grad with a BFA in musical theater from VPA and her audition story, it's a good one. Katie Zaffrann: So, I remember I auditioned across the country for a number of programs. Syracuse was my first audition and it ended up being the standard that I held every other program up to. And I remember so clearly I was singing my song and the auditor who was later one of my professors got up from behind the table and started acting with me. Chris Velardi: What happens next? You'll have to listen to the conversation. She'll finish the story for you. We cover a lot of ground in this 'Cuse conversation, including Katie's time at SU. Her new venture as an instructor with Greenhouse Music, which is an online conservatory, she's teaching a class called The Whole Musician. We also dive deep into the importance of dealing with anxiety and mental health, but we're going to start with the challenges of the last year when you're a performer in a world without performances. So, how are you doing? Katie Zaffrann: I'm hanging in there and I'll be honest. I think I might be doing a little better than some. I wouldn't have said that a year ago, but I actually gave birth about two weeks into lockdown.