Messages of American Popular Song to Women During World War II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt487035r5 No online items Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Michael P. Palmer Processing partially funded by generous grants from Jim Deeton and David Hensley. ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives 909 West Adams Boulevard Los Angeles, California 90007 Phone: (213) 741-0094 Fax: (213) 741-0220 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.onearchives.org © 2009 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Coll2007-020 1 Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Finding Aid to the Ralph W. Judd Collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Collection number: Coll2007-020 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives Los Angeles, California Processed by: Michael P. Palmer, Jim Deeton, and David Hensley Date Completed: September 30, 2009 Encoded by: Michael P. Palmer Processing partially funded by generous grants from Jim Deeton and David Hensley. © 2009 ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Ralph W. Judd collection on Cross-Dressing in the Performing Arts Dates: 1848-circa 2000 Collection number: Coll2007-020 Creator: Judd, Ralph W., 1930-2007 Collection Size: 11 archive cartons + 2 archive half-cartons + 1 records box + 8 oversize boxes + 19 clamshell albums + 14 albums.(20 linear feet). Repository: ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. Los Angeles, California 90007 Abstract: Materials collected by Ralph Judd relating to the history of cross-dressing in the performing arts. The collection is focused on popular music and vaudeville from the 1890s through the 1930s, and on film and television: it contains few materials on musical theater, non-musical theater, ballet, opera, or contemporary popular music. -

Lister); an American Folk Rhapsody Deutschmeister Kapelle/JULIUS HERRMANN; Band of the Welsh Guards/Cap

Guild GmbH Guild -Light Catalogue Bärenholzstrasse 8, 8537 Nussbaumen, Switzerland Tel: +41 52 742 85 00 - e-mail: [email protected] CD-No. Title Track/Composer Artists GLCD 5101 An Introduction Gateway To The West (Farnon); Going For A Ride (Torch); With A Song In My Heart QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT FARNON; SIDNEY TORCH AND (Rodgers, Hart); Heykens' Serenade (Heykens, arr. Goodwin); Martinique (Warren); HIS ORCHESTRA; ANDRE KOSTELANETZ & HIS ORCHESTRA; RON GOODWIN Skyscraper Fantasy (Phillips); Dance Of The Spanish Onion (Rose); Out Of This & HIS ORCHESTRA; RAY MARTIN & HIS ORCHESTRA; CHARLES WILLIAMS & World - theme from the film (Arlen, Mercer); Paris To Piccadilly (Busby, Hurran); HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; DAVID ROSE & HIS ORCHESTRA; MANTOVANI & Festive Days (Ancliffe); Ha'penny Breeze - theme from the film (Green); Tropical HIS ORCHESTRA; L'ORCHESTRE DEVEREAUX/GEORGES DEVEREAUX; (Gould); Puffin' Billy (White); First Rhapsody (Melachrino); Fantasie Impromptu in C LONDON PROMENADE ORCHESTRA/ WALTER COLLINS; PHILIP GREEN & HIS Sharp Minor (Chopin, arr. Farnon); London Bridge March (Coates); Mock Turtles ORCHESTRA; MORTON GOULD & HIS ORCHESTRA; DANISH STATE RADIO (Morley); To A Wild Rose (MacDowell, arr. Peter Yorke); Plink, Plank, Plunk! ORCHESTRA/HUBERT CLIFFORD; MELACHRINO ORCHESTRA/GEORGE (Anderson); Jamaican Rhumba (Benjamin, arr. Percy Faith); Vision in Velvet MELACHRINO; KINGSWAY SO/CAMARATA; NEW LIGHT SYMPHONY (Duncan); Grand Canyon (van der Linden); Dancing Princess (Hart, Layman, arr. ORCHESTRA/JOSEPH LEWIS; QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT Young); Dainty Lady (Peter); Bandstand ('Frescoes' Suite) (Haydn Wood) FARNON; PETER YORKE & HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; LEROY ANDERSON & HIS 'POPS' CONCERT ORCHESTRA; PERCY FAITH & HIS ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/JACK LEON; DOLF VAN DER LINDEN & HIS METROPOLE ORCHESTRA; FRANK CHACKSFIELD & HIS ORCHESTRA; REGINALD KING & HIS LIGHT ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/SERGE KRISH GLCD 5102 1940's Music In The Air (Lloyd, arr. -

The English Listing

THE CROSBY 78's ZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBAthe English listing Members may recall that we issued a THE questionnaire in 1990 seeking views and comments on what we should be providing in CROSBY BING. We are progressively attempting to fulfil 7 8 's these wishes and we now address one major ENGLISH request - a listing of the 78s issued in the UK. LISTING The first time this listing was issued in this form was in the ICC's 1974 booklet and this was updated in 1982in a publication issued by John Bassett's Crosby Collectors Society. The joint compilers were Jim Hayes, Colin Pugh and Bert Bishop. John has kindly given us permission to reproduce part of his publication in BING. This is a complete listing of very English-issued lO-inch and 12-inch 78 rpm shellac record featuring Sing Crosby. In all there are 601 discs on 10different labels. The sheet music used to illustrate some of the titles and the photos of the record labels have been p ro v id e d b y Don and Peter Haizeldon to whom we extend grateful thanks. NUMBERSITITLES LISTING OF ENGLISH 78"s ARIEl GRAND RECORD. THE 110-Inchl 4364 Susiannainon-Bing BRUNSWICK 112-inchl 1 0 5 Gems from "George White's Scandals", Parts 1 & 2 0 1 0 5 ditto 1 0 7 Lawd, you made the night too long/non-Bing 0 1 0 7 ditto 1 1 6 S I. L o u is blues/non-Bing _ 0 1 3 4 Pennies from heaven medley/Pennies from heaven THECROSBYCOLLECTORSSOCIETY BRUNSWICK 110-inchl 1 1 5 5 Just one more chance/Were you sincere? 0 1 6 0 8 Home on the range/The last round-up 0 1 1 5 5 ditto 0 1 6 1 5 Shadow waltz/I've got to sing a torch -

Rebellion Song Collection - Version 17 August 2021

THE IMPOSSIBLE REBELLION - Rebellion Song Collection - Version 17 August 2021 Contents Marcus & Holly’s core songs And When I Rise Be The Change Coal / Warm’s Not Cool Deep Peace Extinction Rebellion Chant Hear The Chant Hebridean Mourning Song If I Had To Rise Up Now Imagine The Impossible Lead With Love Love Rage Rebel One By One Our Planet Calls People Gonna Rise Power To The People Put Your Roots Down Temperature’s Rising Unified And Many We Are Rising (Forest From The Fire) We Are Rising Up We Are The Tongue We're Standing Here We Want To Live When London Lies other relevant song lyrics Bring Me Your Broken Heart Climate Change Challenge Climate Justice (tune of Daisy Daisy) Earth My Body Emergency Ever Rising Sum (tune of House Of The Rising Sun) Ext. Reb.! Right Here! Right Now! Gentle Angry People Go Green (tune of Jolene) Great Turning (aka We Shall Be Known) Hold You In Our Circle I Hear The Silence Calling Me In Dangerous Times It Isn’t Nice (To Block The Courtroom) It's Time To Act Now Join The Rebellion While You May Keep On Walking Forward Let Us Stand Life Is Not Measured Lift Up Your Voices (tune of Freedom Is Coming) Listen To Your Heart Message From Mother Earth Mother Hear Me Calling Motherland Must We Weep And Mourn Never Doubt No Birds In The Air, No Fish In The Sea Raise Up Your Voice And Sing Raise Your Voice ReBella Ciao (aka We Need To Wake Up) Rising Strong Round And Round The Earth Round And Round We Dance Serious Annoyance Seven (October) Nation Army Tall Trees / Mother I Feel You Tall Trees Grow The Children -

Title Composer Lyricist Arranger Cover Artist Publisher Date Notes Sabbath Chimes (Reverie) F

Title Composer Lyricist Arranger Cover artist Publisher Date Notes Sabbath Chimes (Reverie) F. Henri Klickmann Harold Rossiter Music Co. 1913 Sack Waltz, The John A. Metcalf Starmer Eclipse Pub. Co. [1924] Sadie O'Brady Billy Lindemann Billy Lindemann Broadway Music Corp. 1924 Sadie, The Princess of Tenement Row Frederick V. Bowers Chas. Horwitz J.B. Eddy Jos. W. Stern & Co. 1903 Sail Along, Silv'ry Moon Percy Wenrich Harry Tobias Joy Music Inc 1942 Sail on to Ceylon Herman Paley Edward Madden Starmer Jerome R. Remick & Co. 1916 Sailin' Away on the Henry Clay Egbert Van Alstyne Gus Kahn Starmer Jerome H. Remick & Co. 1917 Sailin' Away on the Henry Clay Egbert Van Alstyne Gus Kahn Starmer Jerome H. Remick & Co. 1917 Sailing Down the Chesapeake Bay George Botsford Jean C. Havez Starmer Jerome H. Remick & Co. 1913 Sailing Home Walter G. Samuels Walter G. Samuels IM Merman Words and Music Inc. 1937 Saint Louis Blues W.C. Handy W.C. Handy NA Tivick Handy Bros. Music Co. Inc. 1914 Includes ukulele arrangement Saint Louis Blues W.C. Handy W.C. Handy Barbelle Handy Bros. Music Co. Inc. 1942 Sakes Alive (March and Two-Step) Stephen Howard G.L. Lansing M. Witmark & Sons 1903 Banjo solo Sally in our Alley Henry Carey Henry Carey Starmer Armstronf Music Publishing Co. 1902 Sally Lou Hugo Frey Hugo Frey Robbins-Engel Inc. 1924 De Sylva Brown and Henderson Sally of My Dreams William Kernell William Kernell Joseph M. Weiss Inc. 1928 Sally Won't You Come Back? Dave Stamper Gene Buck Harms Inc. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

The Gothic Trespass in the Life and Songwriting of Tennessee Blues Musician Ray Cashman

DESOLATION BLUES: THE GOTHIC TRESPASS IN THE LIFE AND SONGWRITING OF TENNESSEE BLUES MUSICIAN RAY CASHMAN Victor Bouvéron A thesis submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Folklore in the American Studies Department. Chapel Hill 2017 Approved by: William Ferris Glenn Hinson Crystal O’Leary-Davidson © 2017 Victor Bouvéron ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Victor Bouvéron: Desolation blues: The Gothic trespass in the life and songwriting of Tennessee blues musician Ray Cashman (Under the direction of William Ferris) This thesis explores the pervading feeling of the Gothic in the life and songwriting of Tennessee blues musician Ray Cashman. I argue that Cashman emotionally responds to the South through the framework of the Gothic to assert his identity as a white southern working- class male. As a reader, writer and performer, he trespasses the lines of race and class. The ethnographic fieldwork I conducted in Tennessee, Georgia and North Carolina between 2015 and 2017 led me to reflect on the intriguing relationship between blues, southern Gothic literature and white working-class culture in the South. The songs written by Cashman often express a feeling of desolation, bleakness and decay, invoke a sense of nostalgia for a bygone time, or describe eerie landscapes and supernatural presences. Cashman also retells southern Gothic stories, like “Snake Feast,” inspired by Harry Crews’s A Feast of Snakes. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project started the day I met Bill Ferris in Lille, France, in 2013. Bill encouraged me to apply to UNC-Chapel Hill and introduced me to the field of folklore. -

Title Composer Lyricist Arranger Cover Artist Publisher Date Notes Wabash Blues Fred Meinken Dave Ringle Leo Feist Inc

Title Composer Lyricist Arranger Cover artist Publisher Date Notes Wabash Blues Fred Meinken Dave Ringle Leo Feist Inc. 1921 Wabash Cannon Ball Wm Kindt Wm Kindt NPS Calumet Music Co. 1939 High Bass arranged by Bill Burns Wabash Moon Dave Dreyer Dave Dreyer Irving Berlin Inc. 1931 Wagon Wheels Peter DeRose Billy Hill Shapiro, Bernstein & Co. 1934 Wagon Wheels Peter DeRose Billy Hill Geoffrey O'Hara Shapiro, Bernstein & Co., Inc. 1942 Arranged for male voices (T.T.B.B.) Wah-Hoo! Cliff Friend Cliff Friend hbk Crawford Music Corp. 1936 Wait for Me Mary Charlie Tobias Charlie Tobias Harris Remick Music Corp. 1942 Wait Till the Cows Come Home Ivan Caryll Anne Caldwell Chappell & Company Ltd 1917 Wait Till You Get Them Up In The Air, Boys Albert Von Tilzer Lew Brown EEW Broadway Music Corp. 1919 Waitin' for My Dearie Frederick Loewe Alan Jay Lerner Sam Fox Pub. Co. 1947 Waitin' for the Train to Come In Sunny Skylar Sunny Skylar Martin Block Music 1945 Waiting Harold Orlob Harry L. Cort Shapiro, Bernstein & Co. 1918 Waiting at the Church; or, My Wife Won't Let Me Henry E. Pether Fred W. Leigh Starmer Francis, Day & Hunter 1906 Waiting at the End of the Road Irving Berlin Irving Berlin Irving Berlin Inc. 1929 "Waiting for the Robert E. Lee" Lewis F. Muir L. Wolfe Gilbert F.A. Mills 1912 Waiting for the Robert E. Lee Lewis F. Muir L. Wolfe Gilbert Sigmund Spaeth Alfred Music Company 1939 Waiting in the Lobby of Your Heart Hank Thompson Hank Thompson Brenner Music Inc 1952 Wake The Town and Tell The People Jerry Livingston Sammy Gallop Joy Music Inc 1955 Wake Up, America! Jack Glogau George Graff Jr. -

100% Print Rights Administered by ALFRED 633 SQUADRON MARCH

100% Print Rights administered by ALFRED 633 SQUADRON MARCH (Excluding Europe) Words and Music by RON GOODWIN *A BRIDGE TO THE PAST (from “ Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban ”) Words and Music by JOHN WILLIAMS A CHANGE IS GONNA COME (from “ Malcolm X”) Words and Music by SAM COOKE A CHI (HURT) (Excluding Europe) Words and Music by JIMMIE CRANE and AL JACOBS A CHICKEN AIN’T NOTHING BUT A BIRD Words and Music by EMMETT ‘BABE’ WALLACE A DARK KNIGHT (from “ The Dark Knight ”) Words and Music by HANS ZIMMER and JAMES HOWARD A HARD TEACHER (from “ The Last Samurai ”) Words and Music by HANS ZIMMER A JOURNEY IN THE DARK (from “ The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring”) Music by HOWARD SHORE Lyrics by PHILIPPA BOYENS A MOTHER’S PRAYER (from “ Quest for Camelot ”) Words and Music by CAROLE BAYER SAGER and DAVID FOSTER *A WINDOW TO THE PAST (from “ Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban ”) Words and Music by JOHN WILLIAMS ACCORDION JOE Music by CORNELL SMELSER Lyrics by PETER DALE WIMBROW ACES HIGH MARCH (Excluding Europe) Words and Music by RON GOODWIN AIN'T GOT NO (Excluding Europe) Music by GALT MACDERMOT Lyrics by JAMES RADO and GEROME RAGNI AIN’T MISBEHAVIN’ (from “ Ain’t Misbehavin’ ) (100% in Scandinavia, including Finland) Music by THOMAS “FATS” WALLER and HARRY BROOKS Lyrics by ANDY RAZAF ALL I DO IS DREAM OF YOU (from “ Singin’ in the Rain ”) (Excluding Europe) Music by NACIO HERB BROWN Lyrics by ARTHUR FREED ALL TIME HIGH (from “ Octopussy ”) (Excluding Europe) Music by JOHN BARRY Lyrics by TIM RICE ALMIGHTY GOD (from “ Sacred Concert No. -

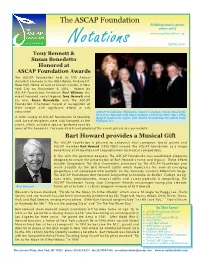

Notations Spring 2011

The ASCAP Foundation Making music grow since 1975 www.ascapfoundation.org Notations Spring 2011 Tony Bennett & Susan Benedetto Honored at ASCAP Foundation Awards The ASCAP Foundation held its 15th Annual Awards Ceremony at the Allen Room, Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center, in New York City on December 8, 2010. Hosted by ASCAP Foundation President, Paul Williams, the event honored vocal legend Tony Bennett and his wife, Susan Benedetto, with The ASCAP Foundation Champion Award in recognition of their unique and significant efforts in arts education. ASCAP Foundation Champion Award recipients Susan Benedetto (l) & Tony Bennett with Mary Rodgers (2nd from left), Mary Ellin A wide variety of ASCAP Foundation Scholarship Barrett (2nd from right), and ASCAP Foundation President Paul and Award recipients were also honored at the Williams (r). event, which included special performances by some of the honorees. For more details and photos of the event, please see our website. Bart Howard provides a Musical Gift The ASCAP Foundation is pleased to announce that composer, lyricist, pianist and ASCAP member Bart Howard (1915-2004) named The ASCAP Foundation as a major beneficiary of all royalties and copyrights from his musical compositions. In line with this generous bequest, The ASCAP Foundation has established programs designed to ensure the preservation of Bart Howard’s name and legacy. These efforts include: Songwriters: The Next Generation, presented by The ASCAP Foundation and made possible by the Bart Howard Estate which showcases the work of emerging songwriters and composers who perform on the Kennedy Center’s Millennium Stage. The ASCAP Foundation Bart Howard Songwriting Scholarship at Berklee College recog- nizes talent, professionalism, musical ability and career potential in songwriting. -

The Movies and Music of the 1930S the Depression Was a Tough Time for Families and Kids Since Money Was Scarce

The Movies and Music of the 1930s The depression was a tough time for families and kids since money was scarce. Even though this was the case and there were no television sets to watch, people managed by swimming in the canals, dancing at the Women’s Club for 25 cents, or going to the movies in Glendale. Here are the top movies that came out during the ’30s as well as the music that came out during this period. 1930 - Top Movies - Tom Sawyer, Top Hat, Animal Crackers, and Hell’s Angels Top Music “Happy Days Are Here Again” (Ben Selvin), “These Little Words” (Duke Ellington), “On the Sunny Side of the Street” (Ted Lewis and his Orchestra) 1931 – Top Movies – Frankenstein, City Lights, Mata Hari, Cimarron - Top Music - “Minnie the Moocher” (Cab Calloway), “Dream a Little Dream of Me” (Wayne King), “Goodnight Sweetheart” (Bing Crosby) 1932 - Top Movies – Tarzan the Ape Man, Trouble in Paradise, The Old Dark House. - Top Music – “All of Me” (Louis Armstrong), “It Don’t Mean a Thing” (Duke Ellington), “Night and Day” (Fred Astaire and Leo Raisman) 1933 - Top Movies – King Kong, 42ndStreet, Dinner at Eight, Sons of the Desert - Top Music – “Stormy Weather” (Ethel Waters), “Sophisticated Lady” (Duke Ellington) “We’re in the Money” (Dick Powell) 1934 - Top Movies – The Thin Man, Cleopatra, It Happened One Night - Top Music – “Moon Glow” (Benny Goodman), “Tumbling Tumbleweeds” (Paul Whitman), “Smoke Gets In Your Eyes” (Paul Whitman), “Cocktails for Two” (Duke Ellington) 1935 - Top Movies – Mutiny on the Bounty, Top Hat, Captain Blood, A Night At the Opera - Top Music – “On the Good Ship Lollipop” (Shirley Temple) “Cheek to Cheek” (Fred Astaire), “The Isle of Capri” (Ray Noble), “Lullaby of Broadway” (Blue Moon) 1936 - Top Movies – The Great Ziegfeld, Mr. -

Sheet Music Collection

McLean County Museum of History Sheet Music Collection Inventoried by Sharon Tallon, Museum Library volunteer German translation by Eleanor Mede April 2012 Collection Information VOLUME OF COLLECTION: Three Boxes COLLECTION DATES: 1870 – 1968 PROVENANCE: None RESTRICTIONS: Collection has several brittle documents. Before making photocopies of items please obtain permission from librarian or archivist. REPRODUCTION RIGHTS: Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection must be obtained in writing from the McLean County Museum of History. ALTERNATIVE FORMATS: None OTHER FINDING AIDS: None LOCATION: Archives Scope Note This collection includes approximately 750 individual pieces of sheet music, booklets and books copyrighted from 1870 through 1968. A few are encapsulated and may appear in displays in the People or Politics room on the Museum’s first floor. Sheet music also is sometimes featured in temporary, but long-running, displays. People who lived in (or once lived in) McLean County donated most, if not all, of the individual sheets, booklets and books of music that represent the 90 years of music listed in this collection. The first section (Box 1, Folders 1 through 6) is devoted to music that has a direct connection to McLean County. Other sections in Box 1 include music with Chicago connections as well as other places in Illinois, a few other states and Canada, as well as cultural and subject-related music. Dance and instrumental music (with or without vocal) make up the bulk of Box 2 along with a listing and some sheet music by Irving Berlin and Walt Disney. Five folders (10, 11, 15, 16, and 17) are devoted to German instrumental music.