If You Lived Here You'd Be Home By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

President's Welcome

PRESIDENT’S WELCOME Friends, Colleagues, and Students, Welcome to the 82nd Annual Mississippi Bandmasters Association State Band Clinic in Natchez. The other members of the MBA Executive Board and I hope that you will experience growth, new perspectives, and renewed aspirations for teaching and learning music in your community during this year’s clinic. I would like to wish all of the students in attendance a heartfelt congratulations on participating in this esteemed event. You represent the very best of the students from your band programs – I encourage you to take that sentiment to heart. Thousands of students have shared in this honor for the last 82 years. Many of you will meet friends this weekend that you will have throughout your life. Lastly, I encourage you to take this opportunity to enjoy making music with others and learning from some of the most outstanding teachers in our country. For members of our association, take the time to visit with the exhibitors and clinicians throughout the weekend. Take advantage of the clinics and presentations that are offered so that you may leave Natchez with new insights and perspectives that you can use with your students at home. Clinic is also a time to renew old friendships and foster new ones. I hope that veteran teachers will take the time to get to know those that are new to our profession and new teachers will seek out the guidance of those with more experience. To our guest clinicians, exhibitors, featured ensembles, and conductors we welcome you and hope that you will enjoy your time with us. -

Access Your Digital Copy Here

“Lainie Love Dalby, it has been powerful to read your essay in Sacred Body Wisdom, PRAISE with your story, passion and purpose. I have not read such honest, living, generative material in a long time. It definitely brought me deep into my own journey and his- tory. I connect with your story from my own experience of separation and disconnec- “I first met Z more than a decade ago at the 11th White Privilege Conference. tion within my body and it is so real and painful, I am just relieved you are speaking Although I had come to the conference to present, I was compelled to attend their your truth about it. I so respect and appreciate your stand for truth and authenticity. workshop for the title alone, “Freeing the body mind spirit from racism,” or some- Your words and expression are powerful medicine for the world.” thing like that. I wanted to know who at this conference was naming the body as a —R.M. site for social struggle and liberation. That was Zahava...The richness of ideas herein, forged in the laboratory of experience and relationship, could fill a whole book. They represent, a good map for the journey of dancing through and beyond “the culture of “As a man reading Eden’s journey I was in for a ride I didn’t expect. A master story whiteness.” It is clear to many that “the story of whiteness” is falling apart. Humanity teller, Eden courageously invites you into an intimate reflection of the reclamation will transform white culture in this generation or the next, or I fear, whiteness will of her sacred body wisdom. -

![[E:] 09 a Second Face.Mp3=2129222 ACDC Whole Lotta Rosie (Rare Live](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7220/e-09-a-second-face-mp3-2129222-acdc-whole-lotta-rosie-rare-live-217220.webp)

[E:] 09 a Second Face.Mp3=2129222 ACDC Whole Lotta Rosie (Rare Live

mTad [E:] 09 A Second face.mp3=2129222 ACDC Whole Lotta Rosie (rare live Bon Scott).mp3=4874280 Damnation of Adam Blessing - Second Damnation - 05 - Back to the River.mp3=5113856 Eddie Van Halen - Eruption (live, rare).mp3=2748544 metallica - CreepingDeath (live).mp3=4129152 [E:\1959 - Miles Davis - Kind Of Blue] 01 So What.mp3=13560814 02 Freddie Freeloader.mp3=14138851 03 Blue In Green.mp3=8102685 04 All Blues.mp3=16674264 05 Flamenco Sketches.mp3=13561792 06 Flamenco Sketches (Alternate Take).mp3=13707024 B000002ADT.01.LZZZZZZZ.jpg=19294 Thumbs.db=5632 [E:\1965 - The Yardbirds & Sonny Boy Williamson] 01 - Bye Bye Bird.mp3=2689034 02 - Mister Downchild.mp3=4091914 03 - 23 Hours Too Long.mp3=5113866 04 - Out Of The Water Coast.mp3=3123210 05 - Baby Don't Worry.mp3=4472842 06 - Pontiac Blues.mp3=3864586 07 - Take It Easy Baby (Ver 1).mp3=4153354 08 - I Don't Care No More.mp3=3166218 09 - Do The Weston.mp3=4065290 10 - The River Rhine.mp3=5095434 11 - A Lost Care.mp3=2060298 12 - Western Arizona.mp3=2924554 13 - Take It Easy Baby (Ver 2).mp3=5455882 14 - Slow Walk.mp3=1058826 15 - Highway 69.mp3=3102730 albumart_large.jpg=11186 [E:\1971 Nazareth] 01 - Witchdoctor Woman.mp3=3994574 02 - Dear John.mp3=3659789 03 - Empty Arms, Empty Heart.mp3=3137758 04 - I Had A Dream.mp3=3255194 05 - Red Light Lady.mp3=5769636 06 - Fat Man.mp3=3292392 07 - Country Girl.mp3=3933959 08 - Morning Dew.mp3=6829163 09 - The King Is Dead.mp3=4603112 10 - Friends (B-side).mp3=3289466 11 - Spinning Top (alternate edit).mp3=2700144 12 - Dear John (alternate edit).mp3=2628673 -

Piano • Vocal • Guitar • Folk Instruments • Electronic Keyboard • Instrumental • Drum ADDENDUM Table of Contents

MUsic Piano • Vocal • Guitar • Folk Instruments • Electronic Keyboard • Instrumental • Drum ADDENDUM table of contents Sheet Music ....................................................................................................... 3 Jazz Instruction ....................................................................................... 48 Fake Books........................................................................................................ 4 A New Tune a Day Series ......................................................................... 48 Personality Folios .............................................................................................. 5 Orchestra Musician’s CD-ROM Library .................................................... 50 Songwriter Collections ..................................................................................... 16 Music Minus One .................................................................................... 50 Mixed Folios .................................................................................................... 17 Strings..................................................................................................... 52 Best Ever Series ...................................................................................... 22 Violin Play-Along ..................................................................................... 52 Big Books of Music ................................................................................. 22 Woodwinds ............................................................................................ -

01 Prelude | | |--02 City of Refuge | | |--03 Bring Me My Queen

|--Abigail Washburn | |--City of Refuge | | |--01 Prelude | | |--02 City of Refuge | | |--03 Bring Me My Queen | | |--04 Chains | | |--05 Ballad of Treason | | |--06 Last Train | | |--07 Burn Thru | | |--08 Corner Girl | | |--09 Dreams Of Nectar | | |--10 Divine Bell | | |--11 Bright Morning Stars | | |--cover | | `--folder | |--Daytrotter Studio | | |--01 City of Refuge | | |--02 Taiyang Chulai | | |--03 Bring Me My Queen | | |--04 Chains | | |--06 What Are They Doing | | `--07 Keys to the Kingdom | |--Live at Ancramdale | | |--01 Main Stageam Set | | |--02 Intro | | |--03 Fall On My Knees | | |--04 Coffee’s Cold | | |--05 Eve Stole The Apple | | |--06 Red & Blazey | | |--07 Journey Home | | |--08 Key To The Kingdom | | |--09 Sometime | | |--10 Abigail talks about the trip to Tibet | | |--11 Song Of The Traveling Daughter | | |--12 Crowd _ Band Intros | | |--13 The Sparrow Watches Over Me | | |--14 Outro | | |--15 Master's Workshop Stage pm Set | | |--16 Tuning, Intro | | |--17 Track 17 of 24 | | |--18 Story about Learning Chinese | | |--19 The Lost Lamb | | |--20 Story About Chinese Reality TV Show | | |--21 Deep In The Night | | |--22 Q & A | | |--23 We’re Happy Working Under The Sun | | |--24 Story About Trip To China | | |--index | | `--washburn2006-07-15 | |--Live at Ballard | | |--01 Introduction | | |--02 Red And Blazing | | |--03 Eve Stole The Apple | | |--04 Free Internet | | |--05 Backstep Cindy_Purple Bamboo | | |--06 Intro. To The Lost Lamb | | |--07 The Lost Lamb | | |--08 Fall On My Knees | | |--Aw2005-10-09 | | `--Index -

Old Time Banjo

|--Compilations | |--Banjer Days | | |--01 Rippling Waters | | |--02 Johnny Don't Get Drunk | | |--03 Hand Me down My Old Suitcase | | |--04 Moonshiner | | |--05 Pass Around the Bottle | | |--06 Florida Blues | | |--07 Cuckoo | | |--08 Dixie Darling | | |--09 I Need a Prayer of Those I Love | | |--10 Waiting for the Robert E Lee | | |--11 Dead March | | |--12 Shady Grove | | |--13 Stay Out of Town | | |--14 I've Been Here a Long Long Time | | |--15 Rolling in My Sweet Baby's Arms | | |--16 Walking in the Parlour | | |--17 Rye Whiskey | | |--18 Little Stream of Whiskey (the dying Hobo) | | |--19 Old Joe Clark | | |--20 Sourwood Mountain | | |--21 Bonnie Blue Eyes | | |--22 Bonnie Prince Charlie | | |--23 Snake Chapman's Tune | | |--24 Rock Andy | | |--25 I'll go Home to My Honey | | `--banjer days | |--Banjo Babes | | |--Banjo Babes 1 | | | |--01 Little Orchid | | | |--02 When I Go To West Virginia | | | |--03 Precious Days | | | |--04 Georgia Buck | | | |--05 Boatman | | | |--06 Rappin Shady Grove | | | |--07 See That My Grave Is Kept Clean | | | |--08 Willie Moore | | | |--09 Greasy Coat | | | |--10 I Love My Honey | | | |--11 High On A Mountain | | | |--12 Maggie May | | | `--13 Banjo Jokes Over Pickin Chicken | | |--Banjo Babes 2 | | | |--01 Hammer Down Girlfriend | | | |--02 Goin' 'Round This World | | | |--03 Down to the Door:Lost Girl | | | |--04 Time to Swim | | | |--05 Chilly Winds | | | |--06 My Drug | | | |--07 Ill Get It Myself | | | |--08 Birdie on the Wire | | | |--09 Trouble on My Mind | | | |--10 Memories of Rain | | | |--12 -

Polydor ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND 3

L1 SKYDORIGINALS 425 16 juni 2013 Arnold Rypens - Kirsten 2:11 1 Little Martha (Allman) Polydor ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND 3 Dit zijn The Originals bij L1 Radio, voor de tweede week op rij met Little Martha van The Allman Brothers Band, de laatste compositie van Duane Allman voor die op 24 jarige leeftijd verongelukte. Rockers van tegenwoordig moeten op die leeftijd hun eerste sporen nog verdienen, Duane had toen al een oeuvre bij elkaar waar nu 7 cd's mee gevuld staan op een Retrospectieve boxset die ons sedert vorige week tot leidraad dient. Waar waren we gebleven? Bij The Weight! 2:47 2 The Weight (Robertson) Rounder KING CURTIS II/25 Een tweede The Weights waar Duane Allman op meespeelt, die van King Curtis, die Duane had leren kennen tijdens de opname van datzelfde nummer maar dan voor Aretha Franklin en daar waren we vorige week gebleven. Duane had de grootste bewondering voor King Curtis om diens unieke mix van soul, blues, gospel & jazz en waar hij wat graag in meeging. Toen Curtis in 1971 in een vuurgevecht om het leven kwam was dat een hele schok voor Duane, ook voor Aretha trouwens die op de begrafenis zong. Bij de eerstvolgende gelegenheid live met zijn Allman Brothers Band versmolt Duane Soul Serenade van King Curtis in een medley met hun You Don't Love Me. We pikken in bij dat Soul Serenade- gedeelte. (starten bij 7:02): (tot 11:20) 4:18 3 Soul Serenade (Ousley/Dixon) Rounder ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND VII/4 Duane 'Skydog' Allman's versie van Soul Serenade was eerder al te horen op de Allman Brothers boxset Dreams, nu ook op Skydog - The Duane Allman Retrospective, mede samengesteld door zijn dochter Galadrielle die werkelijk met de kam door al haar vader's opnamen gegaan is om dan alleen maar hoogtepunten over te houden. -

Home As Archive - Event Transcript

Home As Archive - Event Transcript Event begins Title Slide: Pink background with white text that reads “Home as Archive: Presented in collaboration with Essex Book Festival & Metals Culture, Southend. EWF logo and festival dates are in the lower right corner” Video One: Katerina Bryant Welcome to Home as Archive. My name is Katerina and I will be a host and artist this evening. To begin, I would like to acknowledge the first nations and Traditional Owners of the land we are broadcasting from – I am currently on Kaurna land, where I live and write. I pay my respects to Elders past and present, and, as this is an online recording whose reach is far, to the Elders of the lands this recording might reach. For this event, we will be discussing home, spaces and histories. This is part of the wonderful EWF and is presented in collaboration with Essex Book Festival & Metal Culture, Southend. Tonight, we will be witnessing work by artists working between so-called Australia and Essex, England. They will be sharing artefacts from the archives of their personal histories. I anticipate there will be an intimacy tonight as we will be peering into these artists’ homes. Where we live and, who and what we share those spaces with, is intimate and vulnerable. In some ways the past year has allowed us to peer into each other’s homes over Zoom, but in others it has separated us from sharing space with people we cherish. I’d love to frame tonight as not only a look into these artist’s homes and lives but the creation of our own archive – capturing this moment through place and objects. -

Copy UPDATED KAREOKE 2013

Artist Song Title Disc # ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 6781 10 YEARS THROUGH THE IRIS 13637 WASTELAND 13417 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 9703 CANDY EVERYBODY WANTS 1693 LIKE THE WEATHER 6903 MORE THAN THIS 50 TROUBLE ME 6958 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL SOMEBODY'S BEEN SLEEPING 5612 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 1910 112 DANCE WITH ME 10268 PEACHES & CREAM 9282 RIGHT HERE FOR YOU 12650 112 & LUDACRIS HOT & WET 12569 1910 FRUITGUM CO. 1, 2, 3 RED LIGHT 10237 SIMON SAYS 7083 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 3847 CHANGES 11513 DEAR MAMA 1729 HOW DO YOU WANT IT 7163 THUGZ MANSION 11277 2 PAC & EMINEM ONE DAY AT A TIME 12686 2 UNLIMITED DO WHAT'S GOOD FOR ME 11184 20 FINGERS SHORT DICK MAN 7505 21 DEMANDS GIVE ME A MINUTE 14122 3 DOORS DOWN AWAY FROM THE SUN 12664 BE LIKE THAT 8899 BEHIND THOSE EYES 13174 DUCK & RUN 7913 HERE WITHOUT YOU 12784 KRYPTONITE 5441 LET ME GO 13044 LIVE FOR TODAY 13364 LOSER 7609 ROAD I'M ON, THE 11419 WHEN I'M GONE 10651 3 DOORS DOWN & BOB SEGER LANDING IN LONDON 13517 3 OF HEARTS ARIZONA RAIN 9135 30 SECONDS TO MARS KILL, THE 13625 311 ALL MIXED UP 6641 AMBER 10513 BEYOND THE GREY SKY 12594 FIRST STRAW 12855 I'LL BE HERE AWHILE 9456 YOU WOULDN'T BELIEVE 8907 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY 2815 SECOND CHANCE 8559 3LW I DO 10524 NO MORE (BABY I'MA DO RIGHT) 178 PLAYAS GON' PLAY 8862 3RD STRIKE NO LIGHT 10310 REDEMPTION 10573 3T ANYTHING 6643 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 1412 4 P.M. -

Acoustic Guitar Songs by Title 11Th Street Waltz Sean Mcgowan Sean

Acoustic Guitar Songs by Title Title Creator(s) Arranger Performer Month Year 101 South Peter Finger Peter Finger Mar 2000 11th Street Waltz Sean McGowan Sean McGowan Aug 2012 1952 Vincent Black Lightning Richard Thompson Richard Thompson Nov/Dec 1993 39 Brian May Queen May 2015 50 Ways to Leave Your Lover Paul Simon Paul Simon Jan 2019 500 Miles Traditional Mar/Apr 1992 5927 California Street Teja Gerken Jan 2013 A Blacksmith Courted Me Traditional Martin Simpson Martin Simpson May 2004 A Daughter in Denver Tom Paxton Tom Paxton Aug 2017 A Day at the Races Preston Reed Preston Reed Jul/Aug 1992 A Grandmother's Wish Keola Beamer, Auntie Alice Namakelua Keola Beamer Sep 2001 A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall Bob Dylan Bob Dylan Dec 2000 A Little Love, A Little Kiss Adrian Ross, Lao Silesu Eddie Lang Apr 2018 A Natural Man Jack Williams Jack Williams Mar 2017 A Night in Frontenac Beppe Gambetta Beppe Gambetta Jun 2004 A Tribute to Peador O'Donnell Donal Lunny Jerry Douglas Sep 1998 A Whiter Shade of Pale Keith Reed, Gary Brooker Martin Tallstrom Procul Harum Jun 2011 About a Girl Kurt Cobain Nirvana Nov 2009 Act Naturally Vonie Morrison, Johnny Russel The Beatles Nov 2011 Addison's Walk (excerpts) Phil Keaggy Phil Keaggy May/Jun 1992 Adelita Francisco Tarrega Sep 2018 Africa David Paich, Jeff Porcaro Andy McKee Andy McKee Nov 2009 After the Rain Chuck Prophet, Kurt Lipschutz Chuck Prophet Sep 2003 After You've Gone Henry Creamer, Turner Layton Sep 2005 Ain't It Enough Ketch Secor, Willie Watson Old Crow Medicine Show Jan 2013 Ain't Life a Brook -

Sorted by Title

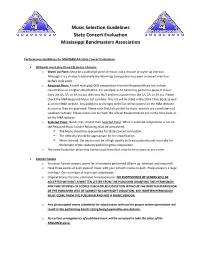

Music Selection Guidelines State Concert Evaluation Mississippi Bandmasters Association Performance Guidelines for MBA/MHSAA State Concert Evaluation • All bands must play three (3) pieces of music. o Warm Up Piece: Must be a published piece of music, not a chorale or warm up exercise. Although it is a choice, traditionally the Warm Up Composition has been a concert march or fanfare style piece. o Required Piece: A band must play ONE composition from the Required Music List in their classification or a higher classification. For example: A 4A band may perform a piece of music from the 4A, 5A, or 6A list but they may NOT perform a piece from the 1A, 2A, or 3A list. Please check the MBA Required Music List carefully. This list will be listed in the State Clinic Book as well as on the MBA website. Any additions or changes to the list will be posted on the MBA Website as soon as they are approved. Please note that lists posted by music vendors are sometimes not updated routinely. Please make sure to check the official Required Music List in the clinic book or on the MBA website. o Selected Piece: Bands may choose their Selected Piece. When a Selected composition is not on the Required Music List the following must be considered: . The Music should be appropriate for State Concert Evaluation. The difficulty should be appropriate for the classification. When learned, the music must be of high quality both educationally and musically for the benefit of the students performing the composition. o The same Evaluation piece may not be used more than once in three years at any event. -

Emergency in Thehighlands

www.ihwebsite.com | facebook.com/highlands.council March 2013 EMERGENCY IN THE HIGHLANDS By Nina Milligan with Maureen Bondor, Highlands Resident of the original “Cottages” neighborhood of an emergency; I don’t like feeling helpless when CERT members learn to help themselves and Are you ready? it is so easy these days to get the basics squared others! The program only runs twice a year and away,” explains Maureen. “Even basic the spring program has two classes beginning on Thanks to Maureen and Michael preparedness (hey that’s about two March 13, 2013. Bondor, IH residents of the original “Cottages” weeks) brings great neighborhood, Issaquah Highlands has many peace of mind. It is an 8-week course, costing only $35. It is CERT-certified neighbors: 40 to 50 at last count. Just go to training that is invaluable and can affect many Maureen and Michael are virtual evangelists when Costco and get people’s lives including your own. Details and it comes to CERT training. But what is CERT it done!” registration can be found at anyway? http://issaquahcitizencorps.com/ We all think CERT stands for Community Emergency about fire, Through CERT Training you learn: Response Team (CERT) and is part of Issaquah earthquake and Disaster First Aid Training Citizen Corps, a volunteer organization dedicated in greater Issaquah, flooding, Disaster Preparedness to helping neighbors be better prepared for as the big threats to our safety. But Basic Firefighting disasters and emergencies. Issaquah’s CERT Maureen says there’s more. “Power Light Search and Rescue program