Whaleboat Heresy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Bedford Whaling

Whaling Capital of the World Park Partners Cultural Effects Lighting the World Sternboard from the brig Scrimshaw Port of Entry Starting in the Colonial era, the finest smokeless, odorless “ The town itself is perhaps Eunice H. Adams, 1845. On voyages that might The whaling industry Americans pursued whales candles. Whale-oil was also the dearest place to live last as long as four employed large num- primarily for blubber to fuel processed into fine industrial in, in all New England. years, whalemen spent bers of African-Ameri- lamps. Whale blubber was lubricating oils. Whale-oil their leisure hours cans, Azoreans, and rendered into oil at high All these brave houses carving and scratching Cape Verdeans, whose from New Bedford ships lit and flowery gardens decorations on sperm communities still flour- temperatures aboard ship—a much of the world from the whale teeth, whale- ish in New Bedford process whalemen called “try- 1830s until petroleum alterna- came from the Atlantic, bone, and baleen. This today. New Bedford’s ing out.” Sperm whales were tives like kerosene and gas re- Pacific, and Indian folk art, known as role in 19th-century prized for their higher-grade placed it in the 1860s. COLLECTION, NEW BEDFORD WHALING MUSEUM scrimshaw, often de- American history was spermaceti oil, used to make oceans. One and all, picted whaling adven- not limited to whaling, they were harpooned Today, New Bedford is a city of The National Park Service National Park Service is to work Heritage Center in Barrow, tures or scenes of however. It was also a nearly 100,000, but its historic joined this partnership in 1996 collaboratively with a wide Alaska, to help recognize the home. -

The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex

WHALING LINGO and the NANTUCKET SLEIGH RIDE 0. WHALING LINGO and the NANTUCKET SLEIGH RIDE - Story Preface 1. THE CREW of the ESSEX 2. FACTS and MYTHS about SPERM WHALES 3. KNOCKDOWN of the ESSEX 4. CAPTAIN POLLARD MAKES MISTAKES 5. WHALING LINGO and the NANTUCKET SLEIGH RIDE 6. OIL from a WHALE 7. HOW WHALE BLUBBER BECOMES OIL 8. ESSEX and the OFFSHORE GROUNDS 9. A WHALE ATTACKS the ESSEX 10. A WHALE DESTROYS the ESSEX 11. GEORGE POLLARD and OWEN CHASE 12. SURVIVING the ESSEX DISASTER 13. RESCUE of the ESSEX SURVIVORS 14. LIFE after the WRECK of the ESSEX Robert E. Sticker created an oil painting interpreting the “Nantucket Sleigh Ride,” an adrenalin-producing event which occurred after whalers harpooned a whale. As the injured whale reacted to the trauma, swimming away from its hunters, it pulled the small whaleboat and its crew behind. Copyright Robert Sticker, all rights reserved. Image provided here as fair use for educational purposes and to acquaint new viewers with Sticker’s work. As more and more Nantucketers hunted, captured and killed whales—including sperm whales—whalers had to travel farther and farther from home to find their prey. In the early 18th century, Nantucketers were finding cachalot (sperm whales) in the middle of the Pacific at a place they called the “Offshore Ground.” A thousand miles, or so, off the coast of Peru, the Offshore Ground seemed to be productive. After taking-on supplies at the Galapagos Islands—including 180 additional large tortoises (from Hood Island) to use as meat when they were so far from land—Captain Pollard and his crew sailed the Essex toward the Offshore Grounds. -

A New Bedford Voyage!

Funding in Part by: ECHO - Education through Cultural and Historical Organizations The Jessie B. DuPont Fund A New Bedford Voyage! 18 Johnny Cake Hill Education Department New Bedford 508 997-0046, ext. 123 Massachusetts 02740-6398 fax 508 997-0018 new bedford whaling museum education department www.whalingmuseum.org To the teacher: This booklet is designed to take you and your students on a voyage back to a time when people thought whaling was a necessity and when the whaling port of New Bedford was known worldwide. I: Introduction page 3 How were whale products used? What were the advantages of whale oil? How did whaling get started in America? A view of the port of New Bedford II: Preparing for the Voyage page 7 How was the whaling voyage organized? Important papers III: You’re on Your Way page 10 Meet the crew Where’s your space? Captain’s rules A day at sea A 24-hour schedule Time off Food for thought from the galley of a whaleship How do you catch a whale? Letters home Your voice and vision Where in the world? IV: The End of the Voyage page 28 How much did you earn? Modern whaling and conservation issues V: Whaling Terms page 30 VI: Learning More page 32 NEW BEDFORD WHALING MUSEUM Editor ECHO Special Projects Illustrations - Patricia Altschuller - Judy Chatfield - Gordon Grant Research Copy Editor Graphic Designer - Stuart Frank, Michael Dyer, - Clara Stites - John Cox - MediumStudio Laura Pereira, William Wyatt Special thanks to Katherine Gaudet and Viola Taylor, teachers at Friends Academy, North Dartmouth, MA, and to Judy Giusti, teacher at New Bedford Public Schools, for their contributions to this publication. -

Modern Whaling

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: In Pursuit of Leviathan: Technology, Institutions, Productivity, and Profits in American Whaling, 1816-1906 Volume Author/Editor: Lance E. Davis, Robert E. Gallman, and Karin Gleiter Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-13789-9 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/davi97-1 Publication Date: January 1997 Chapter Title: Modern Whaling Chapter Author: Lance E. Davis, Robert E. Gallman, Karin Gleiter Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c8288 Chapter pages in book: (p. 498 - 512) 13 Modern Whaling The last three decades of the nineteenth century were a period of decline for American whaling.' The market for oil was weak because of the advance of petroleum production, and only the demand for bone kept right whalers and bowhead whalers afloat. It was against this background that the Norwegian whaling industry emerged and grew to formidable size. Oddly enough, the Norwegians were not after bone-the whales they hunted, although baleens, yielded bone of very poor quality. They were after oil, and oil of an inferior sort. How was it that the Norwegians could prosper, selling inferior oil in a declining market? The answer is that their costs were exceedingly low. The whales they hunted existed in profusion along the northern (Finnmark) coast of Norway and could be caught with a relatively modest commitment of man and vessel time. The area from which the hunters came was poor. Labor was cheap; it also happened to be experienced in maritime pursuits, particularly in the sealing industry and in hunting small whales-the bottlenose whale and the white whale (narwhal). -

By ROBERT F. HEIZER

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 133 Anthropological Papers, No. 24 Aconite Poison Whaling in Asia and America An Aleutian Transfer to the New World By ROBERT F. HEIZER 415 . CONTENTS PAGE Introduction 419 Kamchatka Peninsula-Kurile Islands 421 Japan 422 Koryak 425 Chukchee 426 Aleutian Islands 427 Kodiak Island region 433 Eskimo 439 Northwest Coast 441 Aconite poison 443 General implications of North Pacific whaling 450 Appendix 1 453 The use of poison-harpoons and nets in the modern whale fishery 453 The modern use of heavy nets in whale catching 459 Bibliography 461 ILLUSTRATIONS PLATES 18. The whale fishery of the Greenland Eskimo 468 19. Greenland whales and harpoon with bladder 468 20. Cutting up the whale, Japan 468 21. Dispatching the already harpooned and netted whale with lances, Japan 468 22 Japanese whalers setting out nets for a whale 468 23. The whale hunt of the Aleuts 468 23a. Whale hunt of the Kodiak Island natives (after de Mofras) 468 TEXT FIGURES 56 Whaling methods in the North Pacific and Bering Sea (map) 420 57. Whaling scenes as represented by native artists 423 58. Whaling scenes according to native Eskimo artists 428 59 South Alaskan lance heads of ground slate 432 60. Ordinary whale harpoon and poison harpoon with hinged barbs 455 417 ACONITE POISON WHALING IN ASIA AND AMERICA AN ALEUTIAN TRANSFER TO THE NEW WORLD By Robert F. Heizer INTRODUCTION In this paper I propose to discuss a subject which on its own merits deserves specific treatment, and in addition has the value of present- ing new evidence bearing on the important problem of the interchange of culture between Asia and America via the Aleutian Island chain. -

Artisanal Whaling in the Atlantic: a Comparative Study of Culture, Conflict, and Conservation in St

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2010 Artisanal whaling in the Atlantic: a comparative study of culture, conflict, and conservation in St. Vincent and the Faroe Islands Russell Fielding Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Fielding, Russell, "Artisanal whaling in the Atlantic: a comparative study of culture, conflict, and conservation in St. Vincent and the Faroe Islands" (2010). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 368. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/368 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. ARTISANAL WHALING IN THE ATLANTIC: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF CULTURE, CONFLICT, AND CONSERVATION IN ST. VINCENT AND THE FAROE ISLANDS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Geography and Anthropology Russell Fielding B.S., University of Florida, 2000 M.A., University of Montana, 2005 December, 2010 Dedicated to my mother, who first took me to the sea and taught me to explore. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation has benefitted from the assistance, advice, inspiration, and effort of many people. Kent Mathewson, my advisor and major professor, provided the kind of leadership and direction under which I work best, offering guidance when necessary and allowing me to chart my own course when I was able. -

Old Dartmouth Historical Sketches

-ov* :jS§^. w r-^a-. ^o^ 4 o 4 o i* «o ' jf °o « r ..^'^ ^ *fev* ,CT e ° 4*' * ^ . 0/ • c^5^Vv.^'- O ^oV f± •- «J> * » » ° . ?> v * v' ' 0° *« V" v. i* >6 .....V < O * ^' o r '- V-CV oV ^o« ! 1 tf w ^bv j.°-v •wife; ^°* J^V V^ • ^ a^ /xvV»:* >. c^ s&Btf. ^ WHALING EXHIBITS OF Til E Old Dartmouth Historical Society NEW BEDFORD. MASS. PREPARED P.Y ARTHtR C. WATSON, ASSISTANT-CURATOR. PUBLISHED If) 2 4. BY THE OLD DARTMOUTH HISTORICAL SOCIETY ii PUBLIC ATIOX XO. 53. (REPRINTED ]!)L> <i i The Jl'halinq Museum The Bourne Building ' =%&& _ "O, ^^^ The Rogers Building, with the main entrance to the museum OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, 1926 President—GEORGE H. TRIPP / 'ice-presidents—ZEPHANIAH W. PEASE, JAMES E. STAXTOX, Jr. Treasurer—FREDERIC H. TABER Secretary—MISS ETHEL L. JENNINGS Directors 'George H. Tripp, Zephaniah W. Pease. William W. Crapo, Frederic H. Taber, James E. Stanton, Jr., Miss Rosamond Clifford, Abbott P. Smith, William A. Robinson, Jr.. Oliver F. Brown. Edward L. Macomber, F. Gilbert Hinsdale. Frank Wood, Miss Ethel P. Jennings. ^Curator— Frank Wend. Assistant Curator—Arthur C. Watson. Half-sice Model of the Lagoda THE SOCIETY The Old Dartmouth Historical Society was incorpo- rated in 1903 for the purpose of preserving, through re- search and through the collection of objects of interest, the past history of what was originally the township of Dartmouth, now comprising the city of Xew Bedford and the towns of Westport, Dartmouth, Acushnet and Fairhaven. The formation of such a society came none too soon, for already many of the relics of days gone by had been carried away to other places. -

Historicising Ambergris in the Anthropocene

Historicising Ambergris in the Anthropocene Erin Hortle Figure 1: ‘Ambergris’. Photo: Erin Hortle, 2017. © Australian Humanities Review 63 (November 2018). ISSN: 1325 8338 Australian Humanities Review (November 2018) 49 HIS PIECE OF WRITING IS AN EXPERIMENTAL HISTORY OF A NUGGET OF AMBERGRIS that washed up on the south west coast of Tasmania. It’s also a confession. T When it’s fresh, ambergris smells like briny cow shit, or it smelt like that to me when I sniffed this piece, pictured here. This wasn’t what I expected, given the fact that ambergris is an integral ingredient of perfume. In the twenty-first century its value has dwindled slightly because many perfume makers are now brewing their wares from synthetic substances; however, it remains unsurpassed as a scent stabiliser and fixer and thus is still a much sought-after product that has, at times, been worth more than its weight in gold (Clarke 10). And there it was, sitting on the shoreline of a beach in the remote south west of Tasmania. The shoreline: remote, but not so remote in this globalised world. If you are human, you can only get there by boat or days on foot. But if you are buoyant ambergris, or if you are marine debris—perhaps carelessly tossed into the ocean, or perhaps inadequately fastened to a ship—you can ride the Roaring Forties across the Indian Ocean to arrive on Tasmania’s shores. I’ve struck gold, I thought to myself, when I spied the black little mass. But later I found out that I hadn’t. -

Report on Whaling in St. Vincent and the Grenadines

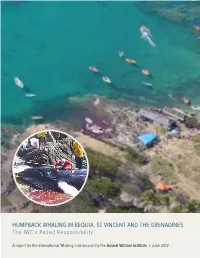

HUMPBACK WHALING IN BEQUIA, ST VINCENT AND THE GRENADINES The IWC’s Failed Responsibility A report for the International Whaling Commission by the Animal Welfare Institute | June 2012 HUMPbacK WHALING INTRODUCTION Since the Caribbean nation of St Vincent and the Grenadines (hereafter SVG) joined the International Whaling Commission (IWC or Commission) IN BEQUIA, in 1981, whalers on the Grenadine island of Bequia are reported to have struck and landed twenty-nine humpback whales (Megaptera ST VINCENT AND novaeangliae) and struck and lost at least five more. While this constitutes a small removal from a population of whales estimated to number over THE GRENADINES 11,0001, it does not excuse the IWC’s three decades of inattention to many problems with the hunt, including the illegal killing of at least nine The IWC’s Failed Responsibility humpback whale calves. Humpback whaling in SVG commenced in 1875 as a primarily commercial activity. In the 1970s, the focus of the operation changed from whale oil for export to meat and blubber for domestic consumption and a small scale artisinal hunt continued in Bequia despite the IWC’s ban on hunting North Atlantic humpback whales. In 1987, the IWC accepted SVG’s assurances that the Bequian whaling operation would not outlast its last surviving harpooner and granted SVG an Aboriginal Subsistence Whaling (ASW) quotai. Since then, the IWC has renewed SVG’s ‘temporary’ ASW quota six more times, including doubling it in 2002, two years after the harpooner died. With the exception of a handful of countries -

Nber Working Paper Series Productivity in American

NBER WORKINGPAPERSERIES PRODUCTIVITY IN AMERICANWHALING: THENEW BEDFORD FLEET IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY Lance Davis Robert Galiman Teresa Hutchins Working Paper No. 2477 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 December 1987 Most of the research on which this paper was based was funded by the National Science Foundation and the NBER project, Productivity and Industrial Change in the World Economy. Grants to Galiman from the Kenan Foundation helped finance the construction of the capital stock estimates. The Division of Humanities and Social Sciences at the California Institute of Technology provided funds for the collection of the labor data. The Carolina Population Center helped plan and carry out the computer operations. We thank in particular Judith Kovenock, Karin Gleiter, Kathleen Gallagher, and Billie Norwood. Paul Cyr, of the New Bedford Public Library, was a kind and helpful guide through the whaling data. Evidence from the Joseph Dias manuscript is published with the permission of the Baker Library of the Graduate School of Business, Harvard University. We thank Michael Butler, Emil Friberg and Eugene Dyar for research assistance. The research reported here is part of the NBER's research program in Development of the American Economy. Any opinions expressed are those of the authors and not those of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER Working Paper #2477 December 1987 Productivity in American Whaling: The New Bedford Fleet in the Nineteenth Century ABSTRACT From the end of the War of 1812 until the Civil War the New Bedford whaling fleet grew spectacularly; thereafter it declined, equally spectacularly. By the end of the century New Bedford's day was over. -

History in a Nutshell the Golden Age of Yankee Whaling

History in a Nutshell The Golden Age of Yankee Whaling Grade Level: 3-5 Learning Objectives: Students will be able to: ● Identify the variety of individuals who worked onboard whaling vessels and explain how they worked together to meet their goals. (Connecticut Social Studies Frameworks HIST 3.3- 5, 4.4-5, 5.4-5; CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.4.6, 5.6; SL.3.1-3, 4.1-4, 5.1-4) ● Explain the economic motivation of 19th- and early 20th-century whalers and identify examples of the resources they sought through the harvesting of whales. (Connecticut Social Studies Frameworks ECO 3.2-3, 4.2-3, 5.2-3; CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.3.1-4, 4.1-4, 5.1-4) ● Use maps to explain New England’s connection to the sea and investigate the journeys taken by whalers during the Golden Age of Yankee Whaling. (Connecticut Social Studies Frameworks GEO 3.1-3, 4.1-3, 5.1-3; CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.3.1-4, 4.1-4, 5.1-4) Program Framework: 1. Introductory video 2. Close-looking activity 3. Independent practice Teacher Background: In this program students will learn about the role and importance of the whaling industry in New England's history. Students will explore the Golden Age of Yankee Whaling through investigating the resources that whales provided, exploring what life was like for a sailor aboard a whaling vessel, and discovering where the voyages took these whalemen. Materials: introductory video, images for close-looking activity, reproducibles for independent practice I. Introductory Video Images Shown 1. -

History of Whaling in and Near North Carolina

NOAA Technical Report NMFS 65 March 1988 History of Whaling In and Near North Carolina Randall R. Reeves Edward Mitchell "II \1.1 '1,\ 1It:.\l"1I .\T ...-:."'· ..·ukT. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Marine Fisheries Service NOAA TECHNICAL REPORT NMFS The major responsibilities of the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) are to monitor and assess the abundance and geographic distribution of fishery resources, to understand and predict fluctuations in the quantity and distribution of these resources, and to establish levels for their optimum use. NMFS is also charged with the development "nd implementation of policies for managing national fishing grounds, development and enforcement of domestic fisheries regulations, surveillance of foreign fishing off United States coastal waters, and the development and enforcement of international fishery agreements and policies. NMFS also assists the fishing industry through marketing service and economic analysis programs, and mortgage insurance and vessel construction subsidies. It collects, analyzes, and publishes statistics on various phases of the industry. The NOAA Technical Report NMFS series was established in 1983 to replace two subcategories of the Technical Reports series: "Special Scientific Report-Fisheries" and "Circular." The series contains the following types of reports: Scientific investigations that document long-term continuing programs of NMFS; intensive scientific reports on studies of restricted scope; papers on applied fishery problems; technical reports of general interest intended to aid conservation and management; reports that review in con siderable detail and at a high technical level certain broad areas of research; and technical papers originating in economics studies and from management investigations.