History in a Nutshell the Golden Age of Yankee Whaling

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Bedford Whaling

Whaling Capital of the World Park Partners Cultural Effects Lighting the World Sternboard from the brig Scrimshaw Port of Entry Starting in the Colonial era, the finest smokeless, odorless “ The town itself is perhaps Eunice H. Adams, 1845. On voyages that might The whaling industry Americans pursued whales candles. Whale-oil was also the dearest place to live last as long as four employed large num- primarily for blubber to fuel processed into fine industrial in, in all New England. years, whalemen spent bers of African-Ameri- lamps. Whale blubber was lubricating oils. Whale-oil their leisure hours cans, Azoreans, and rendered into oil at high All these brave houses carving and scratching Cape Verdeans, whose from New Bedford ships lit and flowery gardens decorations on sperm communities still flour- temperatures aboard ship—a much of the world from the whale teeth, whale- ish in New Bedford process whalemen called “try- 1830s until petroleum alterna- came from the Atlantic, bone, and baleen. This today. New Bedford’s ing out.” Sperm whales were tives like kerosene and gas re- Pacific, and Indian folk art, known as role in 19th-century prized for their higher-grade placed it in the 1860s. COLLECTION, NEW BEDFORD WHALING MUSEUM scrimshaw, often de- American history was spermaceti oil, used to make oceans. One and all, picted whaling adven- not limited to whaling, they were harpooned Today, New Bedford is a city of The National Park Service National Park Service is to work Heritage Center in Barrow, tures or scenes of however. It was also a nearly 100,000, but its historic joined this partnership in 1996 collaboratively with a wide Alaska, to help recognize the home. -

White Whale, Called “Old Tom,” Who Fought Back E? Against the Whalemen Who Were Trying to Kill Him for His Oil

A White n 1834 author Ralph Waldo Emerson was traveling W Ithrough Boston in a carriage. A sailor sitting beside him told h an extraordinary story. For many years the people of New Eng- al land knew of a white whale, called “Old Tom,” who fought back e? against the whalemen who were trying to kill him for his oil. Emerson wrote that this white whale “crushed the boats to small but covered in white patches, spots, and scratches. The white chips in his jaws, the men generally escaping by jumping over- whale that Reynolds described, however, might have been an al- board & being picked up.” The sailor explained that bino, meaning it was born without the normal pigment the whalemen eventually caught Old Tom in in its skin. Though rare, white or colorless individuals the Pacific Ocean, off Peru. occur in most animals, including birds, chimpanzees, Five years later, Jeremiah elephants, and humans. It seems that Amos Smalley, a Reynolds wrote a magazine ar- Native American whaler from Martha’s Vineyard, killed ticle about a sailor in the Pacific a white sperm whale in the South Atlantic in 1902. A few who said he had killed a white years ago, the author and adventurer, Tim Severin, wrote about a whale. This white whale was not white sperm whale witnessed by Pacific Islanders. At least two dif- called Old Tom but was known as ferent white sperm whales have been photographed in the Pacific, “Mocha Dick,” combining the name as have an albino whale shark and, just this winter, a white killer of a local island off Chile, Mocha Is- whale. -

The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex

WHALING LINGO and the NANTUCKET SLEIGH RIDE 0. WHALING LINGO and the NANTUCKET SLEIGH RIDE - Story Preface 1. THE CREW of the ESSEX 2. FACTS and MYTHS about SPERM WHALES 3. KNOCKDOWN of the ESSEX 4. CAPTAIN POLLARD MAKES MISTAKES 5. WHALING LINGO and the NANTUCKET SLEIGH RIDE 6. OIL from a WHALE 7. HOW WHALE BLUBBER BECOMES OIL 8. ESSEX and the OFFSHORE GROUNDS 9. A WHALE ATTACKS the ESSEX 10. A WHALE DESTROYS the ESSEX 11. GEORGE POLLARD and OWEN CHASE 12. SURVIVING the ESSEX DISASTER 13. RESCUE of the ESSEX SURVIVORS 14. LIFE after the WRECK of the ESSEX Robert E. Sticker created an oil painting interpreting the “Nantucket Sleigh Ride,” an adrenalin-producing event which occurred after whalers harpooned a whale. As the injured whale reacted to the trauma, swimming away from its hunters, it pulled the small whaleboat and its crew behind. Copyright Robert Sticker, all rights reserved. Image provided here as fair use for educational purposes and to acquaint new viewers with Sticker’s work. As more and more Nantucketers hunted, captured and killed whales—including sperm whales—whalers had to travel farther and farther from home to find their prey. In the early 18th century, Nantucketers were finding cachalot (sperm whales) in the middle of the Pacific at a place they called the “Offshore Ground.” A thousand miles, or so, off the coast of Peru, the Offshore Ground seemed to be productive. After taking-on supplies at the Galapagos Islands—including 180 additional large tortoises (from Hood Island) to use as meat when they were so far from land—Captain Pollard and his crew sailed the Essex toward the Offshore Grounds. -

A New Bedford Voyage!

Funding in Part by: ECHO - Education through Cultural and Historical Organizations The Jessie B. DuPont Fund A New Bedford Voyage! 18 Johnny Cake Hill Education Department New Bedford 508 997-0046, ext. 123 Massachusetts 02740-6398 fax 508 997-0018 new bedford whaling museum education department www.whalingmuseum.org To the teacher: This booklet is designed to take you and your students on a voyage back to a time when people thought whaling was a necessity and when the whaling port of New Bedford was known worldwide. I: Introduction page 3 How were whale products used? What were the advantages of whale oil? How did whaling get started in America? A view of the port of New Bedford II: Preparing for the Voyage page 7 How was the whaling voyage organized? Important papers III: You’re on Your Way page 10 Meet the crew Where’s your space? Captain’s rules A day at sea A 24-hour schedule Time off Food for thought from the galley of a whaleship How do you catch a whale? Letters home Your voice and vision Where in the world? IV: The End of the Voyage page 28 How much did you earn? Modern whaling and conservation issues V: Whaling Terms page 30 VI: Learning More page 32 NEW BEDFORD WHALING MUSEUM Editor ECHO Special Projects Illustrations - Patricia Altschuller - Judy Chatfield - Gordon Grant Research Copy Editor Graphic Designer - Stuart Frank, Michael Dyer, - Clara Stites - John Cox - MediumStudio Laura Pereira, William Wyatt Special thanks to Katherine Gaudet and Viola Taylor, teachers at Friends Academy, North Dartmouth, MA, and to Judy Giusti, teacher at New Bedford Public Schools, for their contributions to this publication. -

Modern Whaling

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: In Pursuit of Leviathan: Technology, Institutions, Productivity, and Profits in American Whaling, 1816-1906 Volume Author/Editor: Lance E. Davis, Robert E. Gallman, and Karin Gleiter Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-13789-9 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/davi97-1 Publication Date: January 1997 Chapter Title: Modern Whaling Chapter Author: Lance E. Davis, Robert E. Gallman, Karin Gleiter Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c8288 Chapter pages in book: (p. 498 - 512) 13 Modern Whaling The last three decades of the nineteenth century were a period of decline for American whaling.' The market for oil was weak because of the advance of petroleum production, and only the demand for bone kept right whalers and bowhead whalers afloat. It was against this background that the Norwegian whaling industry emerged and grew to formidable size. Oddly enough, the Norwegians were not after bone-the whales they hunted, although baleens, yielded bone of very poor quality. They were after oil, and oil of an inferior sort. How was it that the Norwegians could prosper, selling inferior oil in a declining market? The answer is that their costs were exceedingly low. The whales they hunted existed in profusion along the northern (Finnmark) coast of Norway and could be caught with a relatively modest commitment of man and vessel time. The area from which the hunters came was poor. Labor was cheap; it also happened to be experienced in maritime pursuits, particularly in the sealing industry and in hunting small whales-the bottlenose whale and the white whale (narwhal). -

From Mocha Dick to Moby Dick: Fishing for Clues to Moby's Name and Color

From Mocha Dick to Moby Dick: Fishing for Clues to Moby's Name and Color Ben Rogers University of Delaware Melville's fictional whale Moby Dick appears to derive from the real whale Mocha Dick, yet the differences in names and colors between these two suggest that Moby's name may be intimately connected to his symbolic role. One meaning of mob is 'to wrap in a cowl or veil'. Creating an adjective by adding -y produces moby 'having the qualities of being hooded, especially about the head', a definition reflected in Ishmael's "grand hooded phantom." Dick may be a shortening of Dickens, a euphemism for the devil. Dick may also suggest Dicky 'an officer acting on commission', an appropriate meaning for Ahab' s and Starbuck's conception of Moby as God or an agent of God. Lexicons available to Melville reveal the meaning of the name and illuminate the characteriza- tion of Moby as both commodity and Zeus of the sea, both "dumb brute" and divine Leviathan. The 1929 discovery of a narrative about a white whale named Mocha Dick began 70 years of speculation as to the extent of Mocha as Moby's prototype. The narrative, written by J.R. Reynolds in 1839, described a "renowned monster, who had come off victorious in a hundred fights ... [and was] white as wool." Typical of the reaction of literary critics at the time was Garnett's remark that "Moby Dick ... was but Mocha Dick in faery fiction dressed" (1929, 858). Critical editions of Moby-Dick often include the Reynold's narrative and today scholars generally agree that Melville probably knew of Mocha.1 The obvious sibling qualities of the two whales has tended to center onomastic study on the name Mocha Dick, and subsequent research has attempted to demonstrate that Melville knew of Mocha Dick or, assuming this, to explain why Mocha changed to Moby. -

An Ecocritical Examination of Whale Texts

Econstruction: The Nature/Culture Opposition in Texts about Whales and Whaling. Gregory R. Pritchard B.A. (Deakin) B.A. Honours (Deakin) THESIS SUBMITTED IN TOTAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY. FACULTY OF ARTS DEAKIN UNIVERSITY March 2004 1 Acknowledgements I would like to thank the following people for their assistance in the research and production of this thesis: Associate Professor Brian Edwards, Dr Wenche Ommundsen, Dr Elizabeth Parsons, Glenda Bancell, Richard Smith, Martin Bride, Jane Wilkinson, Professor Mark Colyvan, Dr Rob Leach, Ian Anger and the staff of the Deakin University Library. I would also like to acknowledge with gratitude the assistance of the Australian Postgraduate Award. 2 For Bessie Showell and Ron Pritchard, for a love of words and nature. 3 The world today is sick to its thin blood for lack of elemental things, for fire before the hands, for water welling from the earth, for air, for the dear earth itself underfoot. In my world of beach and dune these elemental presences lived and had their being, and under their arch there moved an incomparable pageant of nature and the year. The flux and reflux of ocean, the incomings of waves, the gatherings of birds, the pilgrimages of the peoples of the sea, winter and storm, the splendour of autumn and the holiness of spring – all these were part of the great beach. The longer I stayed, the more eager was I to know this coast and to share its mysteries and elemental life … Edward Beston, The Outermost House Premises of the machine age. -

North Carolina Folklore

VOLUME XII DECEMBER 1964 NUMBER 2 NORTH CAROLINA FOLKLORE ARTHUR PALMER HUDSON Editor ., a CONTENTS·- ... Page INSTRUMENTAL MUSIC OF THE SOUTHERN APPALACHIANS: TRADITIONAL FIDDLE TUNES, Joan Moser •••••••••• CRITERIA FOR THE MELODIC CLASSIFICATION OF FOLKSONGS, Patricia Mosely • • • • • • • •••• 9 POTATO LORE, Joseph T. McCullen •••••••••••••••• \ 14 UP IN OLD LORAY: FOLKWAYS OF VIOLENCE IN THE GASTONIA STRIKE, Charles W. Joyner • • • • • • • • • 20 THE OLD BLIND MULE, Mrs. John L. Johnson • • • • • ••• 25 NOTE ON "OLD VIRGINIA NEVER TIRE," Jay B. Hubbell 26 SANDLAPPERS AND CLAY EATERS, Francis W. Bradley • 27 "MY EYES ARE DIM -- I CANNOT SEE" ••••••• 29 FOLKLORE IN THE TRACK OF THE CAT, Jack B. Moore 30 BOOK NOTICES Baum: Anglo-Saxon Riddles of the Exeter Book, Archer Taylor • 35 Poe: My First 80 Years, A. P. Hudson • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 37 Warner: Folk Songs and Ballads of the Eastern Seaboard, A. P. Hudson • 38 A Publication of THE NORTH CAROLINA FOLKLORE SOCIETY and THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA FOLKLORE COUNCIL Chapel Hill NORTH CAROLINA FOLKLORE Every reader is invited to submit items or manuscriprs for publication, preferably of the length of those in this issue. Subscriptions, other business communications, and contributions should be sent to Arthur Palmer Hudson Editor of North Carolina Folklore The University of North Carolina 710 Greenwood Road Chapel Hill, North Carolina. Annual subscription, $2 for adults, $1 for students (including membership in The North Carolina Folklore Society). Price of this number, $1. THE NORTH CAROLINA FOLKLORE SOCIETY Holgec 0. Nygard, Durham, President Philip H. Kennedy, Chapel Hill, 1 Vice-President Joan Noser, Brevard, 2 Vice-President Mrs. S, R, Prince, Reidsville, 3 Vice-President A. -

The Hudson River Valley Review

THE HUDSON RIVER VA LLEY REviEW A Journal of Regional Studies MARIST Publisher Thomas S. Wermuth, Vice President for Academic Affairs, Marist College Editors Reed Sparling, writer, Scenic Hudson Christopher Pryslopski, Program Director, Hudson River Valley Institute, Marist College Editorial Board Art Director Myra Young Armstead, Professor of History, Richard Deon Bard College Business Manager Col. Lance Betros, Professor and deputy head, Ann Panagulias Department of History, U.S. Military Academy at West Point The Hudson River Valley Review (ISSN 1546-3486) is published twice Susan Ingalls Lewis, Assistant Professor of History, a year by the Hudson River Valley State University of New York at New Paltz Institute at Marist College. Sarah Olson, Superintendent, Roosevelt- James M. Johnson, Executive Director Vanderbilt National Historic Sites Roger Panetta, Professor of History, Research Assistants Fordham University Richard “RJ” Langlois H. Daniel Peck, Professor of English, Elizabeth Vielkind Vassar College Emily Wist Robyn L. Rosen, Associate Professor of History, Hudson River Valley Institute Marist College Advisory Board David Schuyler, Professor of American Studies, Todd Brinckerhoff, Chair Franklin & Marshall College Peter Bienstock, Vice Chair Thomas S. Wermuth, Vice President of Academic Dr. Frank Bumpus Affairs, Marist College, Chair Frank J. Doherty David Woolner, Associate Professor of History Patrick Garvey & Political Science, Marist College, Franklin Marjorie Hart & Eleanor Roosevelt Institute, Hyde Park Maureen Kangas Barnabas McHenry Alex Reese Denise Doring VanBuren Copyright ©2008 by the Hudson River Valley Institute Tel: 845-575-3052 Post: The Hudson River Valley Review Fax: 845-575-3176 c/o Hudson River Valley Institute E-mail: [email protected] Marist College, 3399 North Road, Web: www.hudsonrivervalley.org Poughkeepsie, NY 12601-1387 Subscription: The annual subscription rate is $20 a year (2 issues), $35 for two years (4 issues). -

By ROBERT F. HEIZER

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 133 Anthropological Papers, No. 24 Aconite Poison Whaling in Asia and America An Aleutian Transfer to the New World By ROBERT F. HEIZER 415 . CONTENTS PAGE Introduction 419 Kamchatka Peninsula-Kurile Islands 421 Japan 422 Koryak 425 Chukchee 426 Aleutian Islands 427 Kodiak Island region 433 Eskimo 439 Northwest Coast 441 Aconite poison 443 General implications of North Pacific whaling 450 Appendix 1 453 The use of poison-harpoons and nets in the modern whale fishery 453 The modern use of heavy nets in whale catching 459 Bibliography 461 ILLUSTRATIONS PLATES 18. The whale fishery of the Greenland Eskimo 468 19. Greenland whales and harpoon with bladder 468 20. Cutting up the whale, Japan 468 21. Dispatching the already harpooned and netted whale with lances, Japan 468 22 Japanese whalers setting out nets for a whale 468 23. The whale hunt of the Aleuts 468 23a. Whale hunt of the Kodiak Island natives (after de Mofras) 468 TEXT FIGURES 56 Whaling methods in the North Pacific and Bering Sea (map) 420 57. Whaling scenes as represented by native artists 423 58. Whaling scenes according to native Eskimo artists 428 59 South Alaskan lance heads of ground slate 432 60. Ordinary whale harpoon and poison harpoon with hinged barbs 455 417 ACONITE POISON WHALING IN ASIA AND AMERICA AN ALEUTIAN TRANSFER TO THE NEW WORLD By Robert F. Heizer INTRODUCTION In this paper I propose to discuss a subject which on its own merits deserves specific treatment, and in addition has the value of present- ing new evidence bearing on the important problem of the interchange of culture between Asia and America via the Aleutian Island chain. -

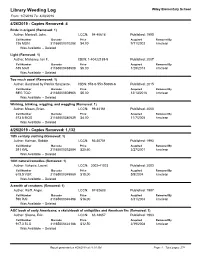

Library Weeding Log Wiley Elementary School From: 1/7/2019 To: 4/29/2019

Library Weeding Log Wiley Elementary School From: 1/7/2019 To: 4/29/2019 4/26/2019 - Copies Removed: 4 Birds in origami (Removed: 1) Author: Montroll, John. LCCN: 94-40618 Published: 1995 Call Number Barcode Price Acquired Removed By 736 MON 31165000310288 $4.00 9/11/2002 kmclean Was Available -- Deleted Light (Removed: 1) Author: Mahaney, Ian F. ISBN: 1-40422185-9 Published: 2007 Call Number Barcode Price Acquired Removed By 535 MAH 31165000468508 $5.00 1/28/2013 kmclean Was Available -- Deleted Too much ooze! (Removed: 1) Author: illustrated by Patrick Spaziante. ISBN: 978-0-553-50866-6 Published: 2015 Call Number Barcode Price Acquired Removed By BEG TOO 31165000508956 $5.00 12/13/2016 kmclean Was Available -- Deleted Winking, blinking, wiggling, and waggling (Removed: 1) Author: Moses, Brian. LCCN: 99-44161 Published: 2000 Call Number Barcode Price Acquired Removed By 573.8 MOS 31165000380539 $4.00 11/7/2005 kmclean Was Available -- Deleted 4/25/2019 - Copies Removed: 1,132 18th century clothing (Removed: 1) Author: Kalman, Bobbie. LCCN: 93-30701 Published: 1993 Call Number Barcode Price Acquired Removed By 391 KAL 31165000352884 $20.60 3/27/2001 kmclean Was Available -- Deleted 1001 natural remedies (Removed: 1) Author: Vukovic, Laurel. LCCN: 2002-41023 Published: 2003 Call Number Barcode Price Acquired Removed By 615.5 VUK 31165000349989 $15.00 5/5/2004 kmclean Was Available -- Deleted A-zenith of creatures (Removed: 1) Author: Raiff, Angie. LCCN: 97-92688 Published: 1997 Call Number Barcode Price Acquired Removed By 590 RAI 31165000346498 $16.00 3/31/2004 kmclean Was Available -- Deleted ABC book of early Americana; a sketchbook of antiquities and American firs (Removed: 1) Author: Sloane, Eric. -

Neptune : the New Yorker

A Reporter at Large: Neptune : The New Yorker http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2007/11/05/071105fa_fac... A REPORTER AT LARGE NEPTUNE’S NAVY Paul Watson’s wild crusade to save the oceans. by Raffi Khatchadourian NOVEMBER 5, 2007 Watson, the founder of the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, a vigilante organization that was founded thirty years ago, with one of its ships, the Farley Mowat, a trawler that has nearly sunk three times. Photograph by James Nachtwey. ne afternoon last winter, two ships lined up side by side in a field of pack ice at the mouth of the Ross Sea, off O the coast of Antarctica. They belonged to the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, a vigilante organization founded by Paul Watson, thirty years ago, to protect the world’s marine life from the destructive habits and the voracious appetites of humankind. Watson and a crew of fifty-two volunteers had sailed the ships—the Farley Mowat, from Australia, and the Robert Hunter, from Scotland—to the Ross Sea with the intention of saving whales in one of their principal habitats. A century ago, when Ernest Shackleton and his crew sailed into the Ross Sea, they discovered so many whales “spouting all around” that they named part of it the Bay of Whales. (“A veritable playground for these monsters,” Shackleton wrote.) During much of the twentieth century, though, whales were intensively hunted in the area, and a Japanese fleet still sails into Antarctic waters every winter to catch minke whales and endangered fin whales. Watson believes in coercive conservation, and for several decades he has been using his private navy to ram whaling and fishing vessels on the high seas.