Choosing to View Morbid Information Involves Reward Circuitry Suzanne Oosterwijk1,2*, Lukas Snoek2,3, Jurriaan Tekoppele1, Lara H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

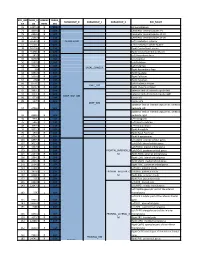

S1 Table. Anatomical Regions of Individual SPES Contacts in Correspondence to Fig 8

S1 Table. Anatomical regions of individual SPES contacts in correspondence to Fig 8. Subject Contact Number Anatomical Region 1 Superior frontal gyrus 2 Central sulcus 3 Lateral occipito-temporal gyrus (fusiform gyrus) #1 4 Superior frontal gyrus 5 Inferior frontal sulcus 6 Middle occipital gyrus 1 Subparietal sulcus 2 Posterior-dorsal part of the cingulate gyrus #2 3 Precuneus 4 Middle-anterior part of the cingulate gyrus and sulcus 5 Sulcus intermedius primus (of Jensen) 1 Inferior part of the precentral sulcus 2 Subcentral gyrus and sulci 3 Inferior part of the precentral sulcus #3 4 Middle-anterior part of the cingulate gyrus and sulcus 5 Middle-anterior part of the cingulate gyrus and sulcus 6 Hippocampus 7 Hippocampus 1 Transverse temporal sulcus 2 Posterior ramus of the lateral sulcus 3 Intraparietal sulcus and transverse parietal sulci 4 Intraparietal sulcus and transverse parietal sulci #4 5 Hippocampus 6 Superior occipital sulcus and transverse occipital sulcus 7 Middle-posterior part of the cingulate gyrus and sulcus 8 Posterior ramus of the lateral sulcus 1 Superior frontal gyrus 2 Superior frontal sulcus #5 3 Middle frontal gyrus 4 Parahippocampal part of the medial occipito-temporal gyrus 5 Middle-anterior part of the cingulate gyrus and sulcus 1 Superior frontal sulcus 2 Posterior-dorsal part of the cingulate gyrus #6 3 Superior frontal gyrus 4 Middle frontal gyrus 1 Inferior frontal sulcus #7 2 Opercular part of the inferior frontal gyrus #8 1 Middle-anterior part of the cingulate gyrus and sulcus 1 Superior frontal sulcus 2 Orbital sulci (H-shaped) #9 3 Superior segment of the circular sulcus of the insula 4 Middle-anterior part of the cingulate gyrus and sulcus . -

Toward a Common Terminology for the Gyri and Sulci of the Human Cerebral Cortex Hans Ten Donkelaar, Nathalie Tzourio-Mazoyer, Jürgen Mai

Toward a Common Terminology for the Gyri and Sulci of the Human Cerebral Cortex Hans ten Donkelaar, Nathalie Tzourio-Mazoyer, Jürgen Mai To cite this version: Hans ten Donkelaar, Nathalie Tzourio-Mazoyer, Jürgen Mai. Toward a Common Terminology for the Gyri and Sulci of the Human Cerebral Cortex. Frontiers in Neuroanatomy, Frontiers, 2018, 12, pp.93. 10.3389/fnana.2018.00093. hal-01929541 HAL Id: hal-01929541 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01929541 Submitted on 21 Nov 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. REVIEW published: 19 November 2018 doi: 10.3389/fnana.2018.00093 Toward a Common Terminology for the Gyri and Sulci of the Human Cerebral Cortex Hans J. ten Donkelaar 1*†, Nathalie Tzourio-Mazoyer 2† and Jürgen K. Mai 3† 1 Department of Neurology, Donders Center for Medical Neuroscience, Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, Netherlands, 2 IMN Institut des Maladies Neurodégénératives UMR 5293, Université de Bordeaux, Bordeaux, France, 3 Institute for Anatomy, Heinrich Heine University, Düsseldorf, Germany The gyri and sulci of the human brain were defined by pioneers such as Louis-Pierre Gratiolet and Alexander Ecker, and extensified by, among others, Dejerine (1895) and von Economo and Koskinas (1925). -

Insular Volume Reductions in Patients with Major Depressive Disorder

Insular volume reductions in patients with major depressive disorder Item Type Article Authors Mutschler, Isabella; Hänggi, Jürgen; Frei, Manuela; Lieb, Roselind; grosse Holforth, Martin; Seifritz, Erich; Spinelli, Simona Citation Mutschler, I., Hänggi, J., Frei, M., Lieb, R., grosse Holforth, M., Seifritz, E., & Spinelli, S. (2019). Insular volume reductions in patients with major depressive disorder. Neurology, Psychiatry and Brain Research, 33, 39–47. doi:10.1016/j.npbr.2019.06.002 Eprint version Post-print DOI 10.1016/j.npbr.2019.06.002 Publisher Elsevier BV Journal Neurology Psychiatry and Brain Research Rights NOTICE: this is the author’s version of a work that was accepted for publication in Neurology Psychiatry and Brain Research. Changes resulting from the publishing process, such as peer review, editing, corrections, structural formatting, and other quality control mechanisms may not be reflected in this document. Changes may have been made to this work since it was submitted for publication. A definitive version was subsequently published in Neurology Psychiatry and Brain Research, [[Volume], [Issue], (2019-06-22)] DOI: 10.1016/ j.npbr.2019.06.002 . © 2019. This manuscript version is made available under the CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 license http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Download date 23/09/2021 13:26:26 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10754/656271 Neurology, Psychiatry and Brain Research 33 (2019) 39–47 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Neurology, -

Cortical Abnormalities in Bipolar Disorder: an MRI Analysis of 6503 Individuals from the ENIGMA Bipolar Disorder Working Group

OPEN Molecular Psychiatry (2018) 23, 932–942 www.nature.com/mp ORIGINAL ARTICLE Cortical abnormalities in bipolar disorder: an MRI analysis of 6503 individuals from the ENIGMA Bipolar Disorder Working Group DP Hibar1,2, LT Westlye3,4,5, NT Doan3,4, N Jahanshad1, JW Cheung1, CRK Ching1,6, A Versace7, AC Bilderbeck8, A Uhlmann9,10, B Mwangi11, B Krämer12, B Overs13, CB Hartberg3, C Abé14, D Dima15,16, D Grotegerd17, E Sprooten18, E Bøen19, E Jimenez20, FM Howells9, G Delvecchio21, H Temmingh9, J Starke9, JRC Almeida22, JM Goikolea20, J Houenou23,24, LM Beard25, L Rauer12, L Abramovic26, M Bonnin20, MF Ponteduro16, M Keil27, MM Rive28,NYao29,30, N Yalin31, P Najt32, PG Rosa33,34, R Redlich17, S Trost27, S Hagenaars35, SC Fears36,37, S Alonso-Lana38,39, TGM van Erp40, T Nickson35, TM Chaim-Avancini33,34, TB Meier41,42, T Elvsåshagen3,43, UK Haukvik3,44, WH Lee18, AH Schene45,46, AJ Lloyd47, AH Young31, A Nugent48, AM Dale49,50, A Pfennig51, AM McIntosh35, B Lafer33, BT Baune52, CJ Ekman14, CA Zarate48, CE Bearden53,54, C Henry23,55, C Simhandl56, C McDonald32, C Bourne8,57, DJ Stein9,10, DH Wolf25, DM Cannon32, DC Glahn29,30, DJ Veltman58, E Pomarol-Clotet38,39, E Vieta20, EJ Canales-Rodriguez38,39, FG Nery33,59, FLS Duran33,34, GF Busatto33,34, G Roberts60, GD Pearlson29,30, GM Goodwin8, H Kugel61, HC Whalley35, HG Ruhe8,28,62, JC Soares11, JM Fullerton13,63, JK Rybakowski64, J Savitz42,65, KT Chaim66,67, M Fatjó-Vilas38,39, MG Soeiro-de-Souza33, MP Boks26, MV Zanetti33,34, MCG Otaduy66,67, MS Schaufelberger33,34, M Alda68, M Ingvar14,69, -

Neural Correlates Underlying Change in State Self-Esteem Hiroaki Kawamichi 1,2,3, Sho K

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Neural correlates underlying change in state self-esteem Hiroaki Kawamichi 1,2,3, Sho K. Sugawara2,4,5, Yuki H. Hamano2,5,6, Ryo Kitada 2,7, Eri Nakagawa2, Takanori Kochiyama8 & Norihiro Sadato 2,5 Received: 21 July 2017 State self-esteem, the momentary feeling of self-worth, functions as a sociometer involved in Accepted: 11 January 2018 maintenance of interpersonal relations. How others’ appraisal is subjectively interpreted to change Published: xx xx xxxx state self-esteem is unknown, and the neural underpinnings of this process remain to be elucidated. We hypothesized that changes in state self-esteem are represented by the mentalizing network, which is modulated by interactions with regions involved in the subjective interpretation of others’ appraisal. To test this hypothesis, we conducted task-based and resting-state fMRI. Participants were repeatedly presented with their reputations, and then rated their pleasantness and reported their state self- esteem. To evaluate the individual sensitivity of the change in state self-esteem based on pleasantness (i.e., the subjective interpretation of reputation), we calculated evaluation sensitivity as the rate of change in state self-esteem per unit pleasantness. Evaluation sensitivity varied across participants, and was positively correlated with precuneus activity evoked by reputation rating. Resting-state fMRI revealed that evaluation sensitivity was positively correlated with functional connectivity of the precuneus with areas activated by negative reputation, but negatively correlated with areas activated by positive reputation. Thus, the precuneus, as the part of the mentalizing system, serves as a gateway for translating the subjective interpretation of reputation into state self-esteem. -

Supplementary Tables

Supplementary Tables: ROI Atlas Significant table grey matter Test ROI # Brainetome area beta volume EG pre vs post IT 8 'superior frontal gyrus, part 4 (dorsolateral area 6), right', 0.773 17388 11 'superior frontal gyrus, part 6 (medial area 9), left', 0.793 18630 12 'superior frontal gyrus, part 6 (medial area 9), right', 0.806 24543 17 'middle frontal gyrus, part 2 (inferior frontal junction), left', 0.819 22140 35 'inferior frontal gyrus, part 4 (rostral area 45), left', 1.3 10665 67 'paracentral lobule, part 2 (area 4 lower limb), left', 0.86 13662 EG pre vs post ET 20 'middle frontal gyrus, part 3 (area 46), right', 0.934 28188 21 'middle frontal gyrus, part 4 (ventral area 9/46 ), left' 0.812 27864 31 'inferior frontal gyrus, part 2 (inferior frontal sulcus), left', 0.864 11124 35 'inferior frontal gyrus, part 4 (rostral area 45), left', 1 10665 50 'orbital gyrus, part 5 (area 13), right', -1.7 22626 67 'paracentral lobule, part 2 (area 4 lower limb), left', 1.1 13662 180 'cingulate gyrus, part 3 (pregenual area 32), right', 0.9 10665 261 'Cerebellar lobule VIIb, vermis', -1.5 729 IG pre vs post IT 16 middle frontal gyrus, part 1 (dorsal area 9/46), right', -0.8 27567 24 'middle frontal gyrus, part 5 (ventrolateral area 8), right', -0.8 22437 40 'inferior frontal gyrus, part 6 (ventral area 44), right', -0.9 8262 54 'precentral gyrus, part 1 (area 4 head and face), right', -0.9 14175 64 'precentral gyrus, part 2 (caudal dorsolateral area 6), left', -1.3 18819 81 'middle temporal gyrus, part 1 (caudal area 21), left', -1.4 14472 -

Altered Resting State Connectivity of the Insular Cortex in Individuals with Fibromyalgia

The Journal of Pain, Vol 15, No 8 (August), 2014: pp 815-826 Available online at www.jpain.org and www.sciencedirect.com Original Reports Altered Resting State Connectivity of the Insular Cortex in Individuals With Fibromyalgia Eric Ichesco,* Tobias Schmidt-Wilcke,*,** Rupal Bhavsar,*,y Daniel J. Clauw,* Scott J. Peltier,z Jieun Kim,x Vitaly Napadow,x,{,k Johnson P. Hampson,* Anson E. Kairys,*,yy David A. Williams,* and Richard E. Harris* *Department of Anesthesiology, Chronic Pain and Fatigue Research Center, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan. yNeurology Department, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. z Functional MRI Laboratory, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan. xMGH/MIT/HMS Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Charlestown, Massachusetts. {Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts. kDepartment of Radiology, Logan College of Chiropractic, Chesterfield, Missouri. **Department of Neurology, Bergmannsheil, Ruhr University Bochum, Bochum, Germany. yyDepartment of Psychology, University of Colorado Denver, Denver, Colorado. Abstract: The insular cortex (IC) and cingulate cortex (CC) are critically involved in pain perception. Previously we demonstrated that fibromyalgia (FM) patients have greater connectivity between the insula and default mode network at rest, and that changes in the degree of this connectivity were associated with changes in the intensity of ongoing clinical pain. In this study we more thoroughly evaluated the degree of resting-state connectivity to multiple regions of the IC in individuals with FM and healthy controls. We also investigated the relationship between connectivity, experimental pain, and current clinical chronic pain. Functional connectivity was assessed using resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging in 18 FM patients and 18 age- and sex-matched healthy controls using predefined seed regions in the anterior, middle, and posterior IC. -

Seed MNI Coordinates Lobe

MNI Coordinates Seed Lobe (Hemisphere) Region BAa X Y Z FP1 -18 62 0 Frontal Lobe (L) Medial Frontal Gyrus 10 FPz 4 62 0 Frontal Lobe (R) Medial Frontal Gyrus 10 FP2 24 60 0 Frontal Lobe (R) Superior Frontal Gyrus 10 AF7 -38 50 0 Frontal Lobe (L) Middle Frontal Gyrus 10 AF3 -30 50 24 Frontal Lobe (L) Superior Frontal Gyrus 9 AFz 4 58 30 Frontal Lobe (R) Medial Frontal Gyrus 9 AF4 36 48 20 Frontal Lobe (R) Middle Frontal Gyrus 10 AF8 42 46 -4 Frontal Lobe (R) Inferior Frontal Gyrus 10 F7 -48 26 -4 Frontal Lobe (L) Inferior Frontal Gyrus 47 F5 -48 28 18 Frontal Lobe (L) Inferior Frontal Gyrus 45 F3 -38 28 38 Frontal Lobe (L) Precentral Gyrus 9 F1 -20 30 50 Frontal Lobe (L) Superior Frontal Gyrus 8 Fz 2 32 54 Frontal Lobe (L) Superior Frontal Gyrus 8 F2 26 32 48 Frontal Lobe (R) Superior Frontal Gyrus 8 F4 42 30 34 Frontal Lobe (R) Precentral Gyrus 9 F6 50 28 14 Frontal Lobe (R) Middle Frontal Gyrus 46 F8 48 24 -8 Frontal Lobe (R) Inferior Frontal Gyrus 47 FT9 -50 -6 -36 Temporal Lobe (L) Inferior Temporal Gyrus 20 FT7 -54 2 -8 Temporal Lobe (L) Superior Temporal Gyrus 22 FC5 -56 4 22 Frontal Lobe (L) Precentral Gyrus 6 FC3 -44 6 48 Frontal Lobe (L) Middle Frontal Gyrus 6 FC1 -22 6 64 Frontal Lobe (L) Middle Frontal Gyrus 6 FCz 4 6 66 Frontal Lobe (R) Medial Frontal Gyrus 6 FC2 28 8 60 Frontal Lobe (R) Sub-Gyral 6 FC4 48 8 42 Frontal Lobe (R) Middle Frontal Gyrus 6 FC6 58 6 16 Frontal Lobe (R) Inferior Frontal Gyrus 44 FT8 54 2 -12 Temporal Lobe (R) Superior Temporal Gyrus 38 FT10 50 -6 -38 Temporal Lobe (R) Inferior Temporal Gyrus 20 T7/T3 -

Anatomy and White Matter Connections of the Superior Frontal Gyrus

Anatomy and White Matter Connections of the Superior Frontal Gyrus Robert G. Briggs, BS1; A. Basit Khan, MD5; Arpan R. Chakraborty, BS2; Carol J Abraham, BS2; Christopher D. Anderson, BA2; Patrick J. Karas, MD5; Phillip A. Bonney, MD1; Ali H. Palejwala, MD2; Andrew K. Conner, MD2; Daniel L. O’Donoghue, PhD3; and Michael E. Sughrue, MD4 1Department of Neurosurgery, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California 2Department of Neurosurgery, University of Oklahoma Health Science Center, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 3Department of Cell Biology, University of Oklahoma Health Science Center, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 4Center for Minimally Invasive Neurosurgery, Prince of Wales Private Hospital, Sydney, Australia 5Department of Neurosurgery, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Texas Running Title: SFG Subcortical Anatomy Keywords: neurology, neurosurgery, white matter, imaging, connectome Corresponding Author: Michael E. Sughrue, MD Suite 3, Level 7 Prince of Wales Private Hospital Barker Street, Randwick New South Wales, 2031 Australia Tel: 02 9650 4940 Fax: 02 9650 4902 Email: [email protected] This article has been accepted for publication and undergone full peer review but has not been through the copyediting, typesetting, pagination and proofreading process which may lead to differences between this version and the Version of Record. Please cite this article as doi: 10.1002/ca.23523 This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved. Funding: None. Declaration of Interests: None. Anatomy and White Matter Connections of the Superior Frontal Gyrus ABSTRACT Introduction. The superior frontal gyrus (SFG) is an important region implicated in a variety of tasks including motor movement, working memory, resting-state and cognitive control. A detailed understanding of the subcortical white matter of the SFG could improve post-operative morbidity related to surgery around this gyrus. -

Normal Cortical Anatomy

Normal Cortical Anatomy MGH Massachusetts General Hospital Harvard Medical School NORMAL CORTICAL ANATOMY • Sagittal • Axial • Coronal • The Central Sulcus NP/MGH Sagittal Neuroanatomy NP/MGH Cingulate sulcus Superior frontal gyrus Marginal ramus of Cingulate sulcus Cingulate gyrus Paracentral lobule Superior parietal lobule Parietooccipital sulcus Cuneus Calcarine sulcus Lingual gyrus Subcallosal gyrus Gyrus rectus Fastigium, fourth ventricle NP/MGH Superior frontal gyrus Cingulate sulcus Precentral gyrus Marginal ramus of Cingulate gyrus Central sulcus Cingulate sulcus Superior parietal lobule Precuneus Parietooccipital sulcus Cuneus Calcarine sulcus Frontomarginal gyrus Lingual gyrus Caudothallamic groove Gyrus rectus NP/MGH Precentral sulcus Central sulcus Superior frontal gyrus Marginal ramus of Corona radiata Cingulate sulcus Superior parietal lobule Precuneus Parietooccipital sulcus Calcarine sulcus Inferior occipital gyrus Lingual gyrus NP/MGH Central sulcus Superior parietal lobule Parietooccipital sulcus Frontopolar gyrus Frontomarginal gyrus Superior occipital gyrus Middle occipital gyrus Medial orbital gyrus Lingual gyrus Posterior orbital gyrus Inferior occipital gyrus Inferior temporal gyrus Temporal horn, lateral ventricle NP/MGH Central sulcus Superior Temporal gyrus Middle Temporal gyrus Inferior Temporal gyrus NP/MGH Central sulcus Superior parietal gyrus Inferior frontal gyrus Frontomarginal gyrus Anterior orbital gyrus Superior occipital gyrus Middle occipital Posterior orbital gyrus gyrus Superior Temporal gyrus Inferior -

Core-Example1.Pdf

ROI_IND NUM_V HEMISP TISSUE_ SUBGROUP_0 SUBGROUP_1 SUBGROUP_2 ROI_NAME EX OX HERE SEG 95 12871.8 B WM corpus callosum 71 4899.8 B GM Cerebellar Vermal Lobules I-V 73 2858.8 B GM Cerebellar Vermal Lobules VIII-X 72 2266.9 B GM Cerebellar Vermal Lobules VI-VII 39 54582.6 L GM CEREBELLUM Left Cerebellum Exterior 41 15500.7 L WM Left Cerebellum White Matter 38 54379.4 R GM Right Cerebellum Exterior 40 15458.7 R WM Right Cerebellum White Matter 30 585.9 L GM Left Accumbens Area 37 3578.9 L GM Left Caudate 56 1597.6 L GM Left Pallidum 58 4942.3 L GM Left Putamen BASAL_GANGLIA 23 526 R GM Right Accumbens Area 36 3651.5 R GM Right Caudate 55 1638.8 R GM Right Pallidum 57 4726 R GM Right Putamen 60 8574.1 L GM Left Thalamus Proper DEEP_GM 59 8256.3 R GM Right Thalamus Proper 92 2887.7 L WM anterior limb of internal capsule left 91 3393.3 R WM anterior limb of internal capsule right DEEP_WM_GM 90 673.6 L WM fornix left 89 517.5 R WM fornix right DEEP_WM posterior limb of internal capsule inc. cerebral 94 2416.3 L WM peduncle left posterior limb of internal capsule inc. cerebral 93 2480.5 R WM peduncle right 32 993.7 L GM Left Amygdala 75 586.5 L GM Left Basal Forebrain 48 3597.7 L GM Left Hippocampus 31 1021.3 R GM Right Amygdala 76 593.1 R GM Right Basal Forebrain 47 3704.7 R GM Right Hippocampus 105 1897.7 L GM Left AOrG anterior orbital gyrus 137 3015.9 L GM Left LOrG lateral orbital gyrus 147 4637.3 L GM Left MOrG medial orbital gyrus 179 2915.7 L GM FRONTAL_INFERIOR_G Left POrG posterior orbital gyrus 104 2244.9 R GM M Right AOrG anterior orbital -

Brain Regions Supporting Verbal Memory Improvement in Healthy Older Subjects Regiões Do Cérebro Relacionadas À Melhora Da Memória Verbal Em Idosos Saudáveis Eliane C

DOI: 10.1590/0004-282X20140120 ARTICLE Brain regions supporting verbal memory improvement in healthy older subjects Regiões do cérebro relacionadas à melhora da memória verbal em idosos saudáveis Eliane C. Miotto1, Joana B. Balardin1, Cary R. Savage2, Maria da Graça M. Martin3, Marcelo C. Batistuzzo1, Edson Amaro Junior3, Ricardo Nitrini1 ABSTRACT Despite growing interest in developing cognitive training interventions to minimize the aging cognitive decline process, no studies have attempted to explore which brain regions support the application of semantic strategies during verbal memory encoding. Our aim was to investigate the behavioral performance and brain correlates of these strategies in elderly individuals using fMRI in healthy older subjects. Method: Subjects were scanned twice on the same day, before and after, directed instructions to apply semantic strategies during the encoding of word lists. Results: Improved memory performance associated to increased semantic strategy application and brain activity in the left inferior and middle and right medial superior prefrontal cortex were found after the directed instructions. There was also reduced activation in areas related to strategy mobilization. Conclusion: Improved memory performance in older subjects after the application of semantic strategies was associated with functional brain reorganization involving regions inside and outside the typical memory network. Keywords: older subjects, semantic strategies, fMRI, episodic memory. RESUMO Apesar do crescente interesse em intervenções de treinamento cognitivo para minimizar o declínio cognitivo do envelhecimento, nenhum estudo explorou quais regiões do cérebro estão relacionadas à aplicação de estratégias semânticas durante a codificação da memória verbal. Nosso objetivo foi investigar o comportamento e correlatos cerebrais associados a essas estratégias usando fMRI em idosos saudáveis.