John Gorell Barnes, First Lord Gorell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Female Art of War: to What Extent Did the Female Artists of the First World War Con- Tribute to a Change in the Position of Women in Society

University of Bristol Department of History of Art Best undergraduate dissertations of 2015 Grace Devlin The Female Art of War: To what extent did the female artists of the First World War con- tribute to a change in the position of women in society The Department of History of Art at the University of Bristol is commit- ted to the advancement of historical knowledge and understanding, and to research of the highest order. We believe that our undergraduates are part of that endeavour. For several years, the Department has published the best of the annual dis- sertations produced by the final year undergraduates in recognition of the excellent research work being undertaken by our students. This was one of the best of this year’s final year undergraduate disserta- tions. Please note: this dissertation is published in the state it was submitted for examination. Thus the author has not been able to correct errors and/or departures from departmental guidelines for the presentation of dissertations (e.g. in the formatting of its footnotes and bibliography). © The author, 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means without the prior permission in writing of the author, or as expressly permitted by law. All citations of this work must be properly acknowledged. Candidate Number 53468 THE FEMALE ART OF THE FIRST WORLD WAR 1914-1918 To what extent did the female artists of the First World War contribute to a change in the position of women in society? Dissertation submitted for the Degree of B.A. -

Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy 1

Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy 1 CHAPTER I. CHAPTER II. CHAPTER III. CHAPTER IV. CHAPTER V. CHAPTER VI. CHAPTER VII. CHAPTER VIII. CHAPTER IX. CHAPTER X. CHAPTER I. CHAPTER II. CHAPTER III. CHAPTER IV. CHAPTER V. CHAPTER VI. CHAPTER VII. CHAPTER VIII. CHAPTER IX. CHAPTER X. Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy The Project Gutenberg EBook of Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy 2 License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy Author: George Biddell Airy Release Date: January 9, 2004 [EBook #10655] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SIR GEORGE AIRY *** Produced by Joseph Myers and PG Distributed Proofreaders AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF SIR GEORGE BIDDELL AIRY, K.C.B., M.A., LL.D., D.C.L., F.R.S., F.R.A.S., HONORARY FELLOW OF TRINITY COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE, ASTRONOMER ROYAL FROM 1836 TO 1881. EDITED BY WILFRID AIRY, B.A., M.Inst.C.E. 1896 PREFACE. The life of Airy was essentially that of a hard-working, business man, and differed from that of other hard-working people only in the quality and variety of his work. It was not an exciting life, but it was full of interest, and his work brought him into close relations with many scientific men, and with many men high in the State. -

Ships!), Maps, Lighthouses

Price £2.00 (free to regular customers) 03.03.21 List up-dated Winter 2020 S H I P S V E S S E L S A N D M A R I N E A R C H I T E C T U R E 03.03.20 Update PHILATELIC SUPPLIES (M.B.O'Neill) 359 Norton Way South Letchworth Garden City HERTS ENGLAND SG6 1SZ (Telephone; 01462-684191 during my office hours 9.15-3.15pm Mon.-Fri.) Web-site: www.philatelicsupplies.co.uk email: [email protected] TERMS OF BUSINESS: & Notes on these lists: (Please read before ordering). 1). All stamps are unmounted mint unless specified otherwise. Prices in Sterling Pounds we aim to be HALF-CATALOGUE PRICE OR UNDER 2). Lists are updated about every 12-14 weeks to include most recent stock movements and New Issues; they are therefore reasonably accurate stockwise 100% pricewise. This reduces the need for "credit notes" and refunds. Alternatives may be listed in case some items are out of stock. However, these popular lists are still best used as soon as possible. Next listings will be printed in 4, 8 & 12 months time so please indicate when next we should send a list on your order form. 3). New Issues Services can be provided if you wish to keep your collection up to date on a Standing Order basis. Details & forms on request. Regret we do not run an on approval service. 4). All orders on our order forms are attended to by return of post. We will keep a photocopy it and return your annotated original. -

Dissertation Title Page

“Singing by Course” and the Politics of Worship in the Church of England, c1560–1640 By James Campbell Nelson Apgar A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Professor James Davies Professor Diego Pirillo Spring 2018 Abstract “Singing by Course” and the Politics of Worship in the Church of England, c1560–1640 by James Campbell Nelson Apgar Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair “Singing by course” was both a product of and a rhetorical tool within the religious discourses of post-Reformation England. Attached to a variety of ostensibly distinct practices, from choirs singing alternatim to congregations praying responsively, it was used to advance a variety of partisan agendas regarding performance and sound within the services of the English Church. This dissertation examines discourses of public worship that were conducted around and through “singing by course,” treating it as a linguistic and conceptual node within broader networks of contemporary religious debate. I thus attend less to the history of the vocal practices to which “by course” and similar descriptions were applied than to the polemical dynamics of these applications. Discussions of these terms and practices slipped both horizontally, to other matters of ritual practice, and vertically, to larger topics or frameworks such as the nature of the Christian Church, the production of piety, and the roles of sound and performance in corporate prayer. Through consideration of these issues, “singing by course” emerges as a rhetorical, political, and theological construction, one that circulated according to changing historical conditions and to the interests of various ecclesiastical constituencies. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Summerfield, Angela (2007). Interventions : Twentieth-century art collection schemes and their impact on local authority art gallery and museum collections of twentieth- century British art in Britain. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University, London) This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/17420/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] 'INTERVENTIONS: TWENTIETH-CENTURY ART COLLECTION SCIIEMES AND TIIEIR IMPACT ON LOCAL AUTHORITY ART GALLERY AND MUSEUM COLLECTIONS OF TWENTIETII-CENTURY BRITISH ART IN BRITAIN VOLUME If Angela Summerfield Ph.D. Thesis in Museum and Gallery Management Department of Cultural Policy and Management, City University, London, August 2007 Copyright: Angela Summerfield, 2007 CONTENTS VOLUME I ABSTRA.CT.................................................................................. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS •........••.••....••........•.•.•....•••.......•....•...• xi CHAPTER 1:INTRODUCTION................................................. 1 SECTION 1 THE NATURE AND PURPOSE OF PUBLIC ART GALLERIES, MUSEUMS AND THEIR ART COLLECTIONS.......................................................................... -

Morris King Thompson, Jr

The Holy Eucharist with The Ordination and Consecration of Morris King Thompson, Jr. As a Bishop in the Church of God and Eleventh Bishop of Louisiana Saturday, May 8, 2010 10:00 AM Christ Church Cathedral New Orleans, Louisiana The People of God and Their Bishop In Christianity’s early centuries, bishops presided over urban churches, functioning as pastors to the Christians of their city and the surrounding countryside. Everyone came into the city on Sunday to participate in the urban liturgy as presided over by the local bishop. These bishops were also our chief theologians, reflecting on the faith in the context of their people’s lives and experiences. It was not until between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries that the parish priest became the usual person to preside over the Eucharistic assembly. The Greek word episcopacy (επισϰοπή) provides the origin of the word “episcopal.” In Greek, the word is related to the idea of visitation, specifically a divine revelation. It came to mean “overseer.” In English, the word means “of or relating to bishops.” In our scriptures, “overseer” was used somewhat interchangeably with the word “elder” (πϱϵσβυτέϱουϛ, presbyteros, from which comes the word priest), for one who leads the fledgling Christian community and holds to sound doctrine despite the danger presented by false teachers (see I Timothy 3:1-7, II Timothy 1:6-10, Titus 1:5-9 and I Peter 5:1-11). The images of a bishop in our Book of Common Prayer are derived from this history. As you will hear in this ordination liturgy, the bishop is understood to be our chief priest and presider of the diocese as well as its chief pastor. -

« ^ T « £ M ? ^ I CHANGES in BRITISH CABINET

THE A/ ^T^JW^-^^SK? BERMUDA COMMERCIAL AH* GENERAL ADVERTISER AND RECORDER. Vol LXXXIV—No. 129 HAMILTON, BERMUDA., THURSDAY, OCTOBER 26. 1911. 20s. PER ANNUM THE FEMALE OF THE SPECIES. A SEA VOLCANO. Moving Pictures Theatres The «^T«£m?^ i CHANGES IN BRITISH A STUDY n* NATURAL HISTORY : BY RUDYARD KIPLING. a^mong the most curious phenomena World Over. ,eas of New Zealand is its sea volcano. This condition owing to long usage elsewhere, When the Himalayan peasant meets the he-bear in his pride, fe a great mountain of black scoria 830 but the moderate-priced houses take CABINET. lie shouts to scare the monster who will often turn aside; feet high, from the top of which, with As far as caa be ascertained there are none but the best films, whkh have But the .she-bear tins accosted reads the peasant tooth and nail, much force, rise white clouds of vapor at least 30,000 moving pkture shows cost a good deal to produce, in which For the female of the species is more deadly than thc male. to a height of fally 2,000 feet. It fe not scattered ©ver the civilised world. In actors aad actresses understand charact- easy travelliag oa che island, for ia places the United States there are over 12,- erizatioa—the real secret of tbe natural BIRREL AND CHURCHILL SWAP. When Nag, the wayside cobra, hears the careless foot of man, the black pebbles of the beach are all 000, where 5,000,000 people, of whom ness of a film. I doubt if a public He wiH .sometimes wriggle sideways and avoid it if he can; astir with water boiling up thiough one-fifth are children, are present every fed on "rush" pictures which purport But his mate makes no such motion where she camps beside the trail— them—water so hot that a misstep might day, spending yearly at least $100,000,- to show in tbe evening the principal scald the foot serioasly. -

Modern British, Irish and East Anglian Art Tuesday 19 November 2013 at 1Pm Knightsbridge, London

Modern British, Irish and East Anglian Art Tuesday 19 November 2013 at 1pm Knightsbridge, London Modern British, Irish and East Anglian Art Tuesday 19 November 2013 at 1pm Knightsbridge Bonhams Bids Enquiries Please see page 2 for bidder Montpelier Street +44 (0) 20 7447 7448 Modern British & Irish Art information including after-sale Knightsbridge +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax Emma Corke collection and shipment London SW7 1HH To bid via the internet please visit +44 (0) 20 7393 3949 www.bonhams.com www.bonhams.com [email protected] Please see back of catalogue for important notice to bidders Viewings Please note that bids should be Shayn Speed submitted no later than 24 hours +44 (0) 20 7393 3909 Illustration [email protected] East Anglian Pictures only before the sale. Front cover: Lot 91 The Guildhall Back cover: Lot 216 East Anglian Pictures Guildhall Street New bidders must also provide Inside front: Lot 46 Daniel Wright Bury St Edmunds proof of identity when submitting Inside back: Lot 215 +44 (0) 1284 716195 Suffolk, IP33 1PS bids. Failure to do this may result [email protected] in your bids not being processed. Tuesday 5 November 9am to 7pm Bidding by telephone will only be Customer Services Monday to Friday 8.30am to 6pm Wednesday 6 November accepted on a lot with a lower +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 9am to 4pm estimate in excess of £400. ----------- St Michael’s Hall Sale Number: 20779 Church Street Live online bidding is Reepham available for this sale Catalogue: £12 Norfolk, NR10 4JW Please email [email protected] with “Live bidding” in the subject Tuesday 12 November line 48 hours before the auction 9am to 7pm to register for this service. -

AUTOBIOGRAPHY of SIR GEORGE BIDDELL AIRY, K.C.B., By

AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF SIR GEORGE BIDDELL AIRY, K.C.B., By George Biddell Airy CHAPTER I. PERSONAL SKETCH OF GEORGE BIDDELL AIRY. The history of Airy's life, and especially the history of his life's work, is given in the chapters that follow. But it is felt that the present Memoir would be incomplete without a reference to those personal characteristics upon which the work of his life hinged and which can only be very faintly gathered from his Autobiography. He was of medium stature and not powerfully built: as he advanced in years he stooped a good deal. His hands were large-boned and well-formed. His constitution was remarkably sound. At no period in his life does he seem to have taken the least interest in athletic sports or competitions, but he was a very active pedestrian and could endure a great deal of fatigue. He was by no means wanting in physical courage, and on various occasions, especially in boating expeditions, he ran considerable risks. In debate and controversy he had great self-reliance, and was absolutely fearless. His eye-sight was peculiar, and required correction by spectacles the lenses of which were ground to peculiar curves according to formulae which he himself investigated: with these spectacles he saw extremely well, and he commonly carried three pairs, adapted to different distances: he took great interest in the changes that took place in his eye-sight, and wrote several Papers on the subject. In his later years he became somewhat deaf, but not to the extent of serious personal inconvenience. -

THE LIFE-BOAT. JOURNAL of the National Xffe^Boat Jnstitution, (ISSUED QUARTERLY.)

THE LIFE-BOAT. JOURNAL OF THE National Xffe^Boat Jnstitution, (ISSUED QUARTERLY.) VOL. XXI.—No. 245.] IST AUGUST, 1912. [PRICE 3d. LIGHTING THE BEACH. SAILORS have always been famous for between walls or gate-posts for the the keenness of their vision, and more carriage to pass. Sometimes it lies over especially for a power, beyond that of a rough foreshore, where the greatest the average man of seeing clearly at care must be taken to avoid hummocks night; but of those who serve the sea, of rock or large boulders, and sometimes none perhaps has this gift in larger over a sandy beach full of deep pools, or measure than the coast fisherman, who " lows," as they are called colloquially ; forms so much the largest proportion or with patches of soft mud where the of the crews of our Life-boats. The wheels of the carriage may sink. nature of his -work will account for The larger types of boats, launched this. Long hours of. toil -with net or on what are known as " roller-skids," line, through moonless nights, have require even more careful manipulation developed the faculty; and the way than those which are small enough for he will take his boat into harbour on a transporting carriage. A couple of a dark night, or steer her through a inches too much to the right or left and narrow channel with only the black the keel misses the roller and buries water between the white of the breakers itself in sand or shingle. As these on either hand to guide him, always boats often weigh from 8 to 10 tons, strikes the landsman with astonishment the hoisting of one of them on to the and admiration. -

Aryan Nations Deflates

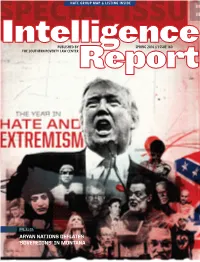

HATE GROUP MAP & LISTING INSIDE PUBLISHED BY SPRING 2016 // ISSUE 160 THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER PLUS: ARYAN NATIONS DEFLATES ‘SOVEREIGNS’ IN MONTANA EDITORIAL A Year of Living Dangerously BY MARK POTOK Anyone who read the newspapers last year knows that suicide and drug overdose deaths are way up, less edu- 2015 saw some horrific political violence. A white suprem- cated workers increasingly are finding it difficult to earn acist murdered nine black churchgoers in Charleston, S.C. a living, and income inequality is at near historic lev- Islamist radicals killed four U.S. Marines in Chattanooga, els. Of course, all that and more is true for most racial Tenn., and 14 people in San Bernardino, Calif. An anti- minorities, but the pressures on whites who have his- abortion extremist shot three people to torically been more privileged is fueling real fury. death at a Planned Parenthood clinic in It was in this milieu that the number of groups on Colorado Springs, Colo. the radical right grew last year, according to the latest But not many understand just how count by the Southern Poverty Law Center. The num- bad it really was. bers of hate and of antigovernment “Patriot” groups Here are some of the lesser-known were both up by about 14% over 2014, for a new total political cases that cropped up: A West of 1,890 groups. While most categories of hate groups Virginia man was arrested for allegedly declined, there were significant increases among Klan plotting to attack a courthouse and mur- groups, which were energized by the battle over the der first responders; a Missourian was Confederate battle flag, and racist black separatist accused of planning to murder police officers; a former groups, which grew largely because of highly publicized Congressional candidate in Tennessee allegedly conspired incidents of police shootings of black men. -

Episcopal Tombs in Early Modern England

Jnl of Ecclesiastical History, Vol. 55, No. 4, October 2004. f 2004 Cambridge University Press 654 DOI: 10.1017/S0022046904001502 Printed in the United Kingdom Episcopal Tombs in Early Modern England by PETER SHERLOCK The Reformation simultaneously transformed the identity and role of bishops in the Church of England, and the function of monuments to the dead. This article considers the extent to which tombs of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century bishops represented a set of episcopal ideals distinct from those conveyed by the monuments of earlier bishops on the one hand and contemporary laity and clergy on the other. It argues that in death bishops were increasingly undifferentiated from other groups such as the gentry in the dress, posture, location and inscriptions of their monuments. As a result of the inherent tension between tradition and reform which surrounded both bishops and tombs, episcopal monuments were unsuccessful as a means of enhancing the status or preserving the memory and teachings of their subjects in the wake of the Reformation. etween 1400 and 1700, some 466 bishops held office in England and Wales, for anything from a few months to several decades.1 The B majority died peacefully in their beds, some fading into relative obscurity. Others, such as Richard Scrope, Thomas Cranmer and William Laud, were executed for treason or burned for heresy in one reign yet became revered as saints, heroes or martyrs in another. Throughout these three centuries bishops played key roles in the politics of both Church and PRO=Public Record Office; TNA=The National Archives I would like to thank Craig D’Alton, Felicity Heal, Clive Holmes, Ralph Houlbrooke, Judith Maltby, Keith Thomas and the anonymous reader for this JOURNAL for their comments on this article.