Statement of Marshall S. Huebner, Partner, Davis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK

CC22 N848AE HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 5 £1 CC203 OK-HFM Tupolev Tu-134 CSA -large OK on fin 91 2 £3 CC211 G-31-962 HP Jetstream 31 American eagle 92 2 £1 CC368 N4213X Douglas DC-6 Northern Air Cargo 88 4 £2 CC373 G-BFPV C-47 ex Spanish AF T3-45/744-45 78 1 £4 CC446 G31-862 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC487 CS-TKC Boeing 737-300 Air Columbus 93 3 £2 CC489 PT-OKF DHC8/300 TABA 93 2 £2 CC510 G-BLRT Short SD-360 ex Air Business 87 1 £2 CC567 N400RG Boeing 727 89 1 £2 CC573 G31-813 HP Jetstream 31 white 88 1 £1 CC574 N5073L Boeing 727 84 1 £2 CC595 G-BEKG HS 748 87 2 £2 CC603 N727KS Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC608 N331QQ HP Jetstream 31 white 88 2 £1 CC610 D-BERT DHC8 Contactair c/s 88 5 £1 CC636 C-FBIP HP Jetstream 31 white 88 3 £1 CC650 HZ-DG1 Boeing 727 87 1 £2 CC732 D-CDIC SAAB SF-340 Delta Air 89 1 £2 CC735 C-FAMK HP Jetstream 31 Canadian partner/Air Toronto 89 1 £2 CC738 TC-VAB Boeing 737 Sultan Air 93 1 £2 CC760 G31-841 HP Jetstream 31 American Eagle 89 3 £1 CC762 C-GDBR HP Jetstream 31 Air Toronto 89 3 £1 CC821 G-DVON DH Devon C.2 RAF c/s VP955 89 1 £1 CC824 G-OOOH Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 3 £1 CC826 VT-EPW Boeing 747-300 Air India 89 3 £1 CC834 G-OOOA Boeing 757 Air 2000 89 4 £1 CC876 G-BHHU Short SD-330 89 3 £1 CC901 9H-ABE Boeing 737 Air Malta 88 2 £1 CC911 EC-ECR Boeing 737-300 Air Europa 89 3 £1 CC922 G-BKTN HP Jetstream 31 Euroflite 84 4 £1 CC924 I-ATSA Cessna 650 Aerotaxisud 89 3 £1 CC936 C-GCPG Douglas DC-10 Canadian 87 3 £1 CC940 G-BSMY HP Jetstream 31 Pan Am Express 90 2 £2 CC945 7T-VHG Lockheed C-130H Air Algerie -

TWA's Caribbean Flights Caribbean Cure for The

VOLUME 48 NUMBER 9 MAY 6, 1985 Caribbean . TWA's Caribbean Flights Cure for The Doldrums TWA will fly to the Caribbean this fall, President Ed Meyer announced. The air line willserve nine Caribbean destinations from New York starting November 15; at the same time, it will inaugurate non-stop service between St. Louis and SanJuan. Islands to be served are St. Thomas, the Bahamas, St. Maarten, St. Croix, Antigua, Martinique, Guadeloupe and Puerto Rico. For more than a decade TWA has con sistently been the leading airline across . the North Atlantic in terms of passengers carried. With the addition of the Caribbean routes, TWA willadd an important North South dimension to its internationalserv ices, Mr. Meyer said. "We expect that strong winter loads to Caribbean vacation destinations will help TWA counterbalance relatively light transatlantic traffic at that time of year, . and vice versa," he explained. "Travelers willbenefit from TWA's premiere experi ence in international operations and its reputation for excellent service," he added. Mr. Meyer emphasized TWA's leader ship as the largest tour operator across the Atlantic, and pointed to the airline's feeder network at both Kennedy and St. Louis: "Passengers from the west and midwest caneasily connect into these ma- (topage4) Freeport � 1st Quarter: Nassau SAN JUAN A Bit Better St. Thomas With the publication of TWA's first-quar St. Croix ter financial results,· the perennial ques tion recurs: "With load factors like that, how could we lose so much money?" Martinique As always, the answer isn't simple. First the numbers, then the words. -

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

Approve Airline Lease with Allegiant Air LLC

DRAFT Agenda Item 3 AGENDA STAFF REPORT ASR Control 20-00 l 077 MEETING DATE: 01 /1 2/21 LEGAL ENTITY TAKING ACTION: Board ofSupervisors BOARD OF SUPERVISORS DISTRICT(S): 2 SUBMITTING AGENCY/DEPARTMENT: John Wayne Airport (Approved) DEPARTMENT CONTACT PERSON(S): Barry A. Rondinella (949) 252-5183 Dave Pfeiffer (949) 252-5291 SUBJECT: Approve Airline Lease with Allegiant Air LLC CEO CONCUR COUNTY COUNSEL REVIEW CLERK OF THE BOARD Concur Approved Agreement to Form Discussion 4/5 Vote Budgeted: Yes Current Year Cost: NI A Annual Cost: NIA Staffing Impact: No # of Positions: Sole Source: No Current Fiscal Year Revenue: $614,681 Funding Source: Airport Operating Fund 280: 100% County Audit in last 3 years: No Prior Board Action: 11/03/2020 #6 RECOMMENDED ACTION(S): 1. Approve and execute the Certificated Passenger Airline Lease with Allegiant Air LLC, for a term effective February 1, 2021, through December 31, 2025. 2. Authorize John Wayne Airport to allocate three Regulated Class A Average Daily Departures and seat capacity, effective February I, 2021, through December 31, 2025, consistent with the terms of the Phase 2 Commercial Airline Access Plan and Regulation. 3. Authorize the Airport Director or designee to make minor modifications and amendments to the lease that do not materially alter the terms or financial obligations to the County and perform all activities specified under the terms ofthe lease. SUMMARY: Approval of the Certificated Passenger Airline Lease between the County of Orange and Allegiant Air LLC and approval of the allocation of operating capacity will allow Allegiant Air LLC, a new carrier from the commercial air carrier new entrant waiting list, to initiate operations at John Wayne Airport. -

Airline Schedules

Airline Schedules This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on January 08, 2019. English (eng) Describing Archives: A Content Standard Special Collections and Archives Division, History of Aviation Archives. 3020 Waterview Pkwy SP2 Suite 11.206 Richardson, Texas 75080 [email protected]. URL: https://www.utdallas.edu/library/special-collections-and-archives/ Airline Schedules Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Series Description .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 - Page 2 - Airline Schedules Summary Information Repository: -

Integrated Report 2020 Index

INTEGRATED REPORT 2020 INDEX 4 28 70 92 320 PRESENTATION CORPORATE GOVERNANCE SECURITY METHODOLOGY SWORN STATEMENT 29 Policies and practices 71 Everyone’s commitment 93 Construction of the report 31 Governance structure 96 GRI content index 35 Ownership structure 102 Global Compact 5 38 Policies 103 External assurance 321 HIGHLIGHTS 74 104 Glossary CORPORATE STRUCTURE LATAM GROUP EMPLOYEES 42 75 Joint challenge OUR BUSINESS 78 Who makes up LATAM group 105 12 81 Team safety APPENDICES 322 LETTER FROM THE CEO 43 Industry context CREDITS 44 Financial results 47 Stock information 48 Risk management 83 50 Investment plan LATAM GROUP CUSTOMERS 179 14 FINANCIAL INFORMATION INT020 PROFILE 84 Connecting people This is a 86 More digital travel experience 180 Financial statements 2020 navigable PDF. 15 Who we are 51 270 Affiliates and subsidiaries Click on the 17 Value generation model SUSTAINABILITY 312 Rationale buttons. 18 Timeline 21 Fleet 52 Strategy and commitments 88 23 Passenger operation 57 Solidary Plane program LATAM GROUP SUPPLIERS 25 LATAM Cargo 62 Climate change 89 Partner network 27 Awards and recognition 67 Environmental management and eco-efficiency Presentation Highlights Letter from the CEO Profile Corporate governance Our business Sustainability Integrated Report 2020 3 Security Employees Customers Suppliers Methodology Appendices Financial information Credits translated at the exchange rate of each transaction date, • Unless the context otherwise requires, references to “TAM” although a monthly rate may also be used if exchange rates are to TAM S.A., and its consolidated affiliates, including do not vary widely. TAM Linhas Aereas S.A. (“TLA”), which operates under the name “LATAM Airlines Brazil”, Fidelidade Viagens e Turismo Conventions adopted Limited (“TAM Viagens”), and Transportes Aéreos Del * Unless the context otherwise requires, references to Mercosur S.A. -

European Airports Fact Sheet

European Airports from the 1960s to the 1980s To support the commentary on this DVD, AVION VIDEO has produced this complimentary Fact Sheet listing all the aircraft featured, in the order of their first appearance. PLEASE RETURN THE SLIP BELOW TO RECEIVE A FREE CATALOGUE KLM Viscount V803 Pan American 707-121 BEA Vanguard V953 G-APEK USAF C9A Nightingale Trans Arabia Airways DC6B 9K-ABB Air France 727-200 TAP Caravelle VI-R CS-TCB Laker Airways DC10-10 G-AZZD Air Ceylon Comet 4 G-APDH Pan American 707-121 Air France L1049G Super Constellation F-BHBG Laker Airways BAC1-11 320AZ G-AVBY Iberia Caravelle VI-R EC-ARK Aeroamerica 720-027 KLM L188 Electra II Dan Air BAC 1-11 401AK G-AXCK Air France Caravelle III F-BHRU French A.F. Nord 262 Sabena CV440 Dan Air BAC 1-11 Qantas 707-138 VH-EBA French A.F. Noratlas 312 BA British Westpoint Airlines DC3 G-AJHY Intl. Caribbean Airways 707-138B G-AVZZ BOAC [Nigeria Airways] 707-436 G-ARRA French A.F. DC6A KLM Viscount V803 PH-VIA Jersey Airlines Herald Finnair Caravelle III Derby Airways DC3 Aer Lingus DC3 EI-AFA KLM Viscount V803 Iraqi Airways Viscount V735 YI-ACL Fairways Rotterdam DC3 PH-SCC JAT Caravelle VI-N YU-AHB Channel Airways Viking US Navy R4Y Channel Airways DC3 TWA 707-331 N763TW Aer Lingus F27 BOAC Comet 4 G-APDR Aer Lingus 720-048 EI-ALA Cunard Eagle Viscount V755 G-AOCB Sabena DC6B South African Airways 707-344 British Eagle Viscount 700 East African Airways Comet 4 VP-KPK Channel Airways Viscount 812 Dan Air 707-321 G-AZTG BKS Avro 748 Air France Concorde F-BVFA Dan Air DC3 Air France -

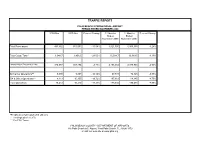

Traffic Report

TRAFFIC REPORT PALM BEACH INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT PERIOD ENDED NOVEMBER 2008 2008/Nov 2007/Nov Percent Change 12 Months 12 Months Percent Change Ended Ended November 2008 November 2007 Total Passengers 493,852 561,053 -11.98% 6,521,590 6,955,356 -6.24% Total Cargo Tons * 1,048.7 1,456.6 -28.00% 15,584.7 16,083.5 -3.10% Landed Weight (Thousands of Lbs.) 326,077 357,284 -8.73% 4,106,354 4,370,930 -6.05% Air Carrier Operations** 5,099 5,857 -12.94% 67,831 72,125 -5.95% GA & Other Operations*** 8,313 10,355 -19.72% 107,861 118,145 -8.70% Total Operations 13,412 16,212 -17.27% 175,692 190,270 -7.66% H17 + H18 + H19 + H20 13,412.0000 16,212.0000 -17.27% 175,692.0000 190,270.0000 -7.66% * Freight plus mail reported in US tons. ** Landings plus takeoffs. *** Per FAA Tower. PALM BEACH COUNTY - DEPARTMENT OF AIRPORTS 846 Palm Beach Int'l. Airport, West Palm Beach, FL 33406-1470 or visit our web site at www.pbia.org TRAFFIC REPORT PALM BEACH INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT AIRLINE PERCENTAGE OF MARKET November 2008 2008/Nov 12 Months Ended November 2008 Enplaned Market Share Enplaned Market Share Passengers Passengers Total Enplaned Passengers 246,559 100.00% 3,273,182 100.00% Delta Air Lines, Inc. 54,043 21.92% 676,064 20.65% JetBlue Airways 50,365 20.43% 597,897 18.27% US Airways, Inc. 36,864 14.95% 470,538 14.38% Continental Airlines, Inc. -

Bankruptcy Tilts Playing Field Frank Boroch, CFA 212 272-6335 [email protected]

Equity Research Airlines / Rated: Market Underweight September 15, 2005 Research Analyst(s): David Strine 212 272-7869 [email protected] Bankruptcy tilts playing field Frank Boroch, CFA 212 272-6335 [email protected] Key Points *** TWIN BANKRUPTCY FILINGS TILT PLAYING FIELD. NWAC and DAL filed for Chapter 11 protection yesterday, becoming the 20 and 21st airlines to do so since 2000. Now with 47% of industry capacity in bankruptcy, the playing field looks set to become even more lopsided pressuring non-bankrupt legacies to lower costs further and low cost carriers to reassess their shrinking CASM advantage. *** CAPACITY PULLBACK. Over the past 20 years, bankrupt carriers decreased capacity by 5-10% on avg in the year following their filing. If we assume DAL and NWAC shrink by 7.5% (the midpoint) in '06, our domestic industry ASM forecast goes from +2% y/y to flat, which could potentially be favorable for airline pricing (yields). *** NWAC AND DAL INTIMATE CAPACITY RESTRAINT. After their filing yesterday, NWAC's CEO indicated 4Q:05 capacity could decline 5-6% y/y, while Delta announced plans to accelerate its fleet simplification plan, removing four aircraft types by the end of 2006. *** BIGGEST BENEFICIARIES LIKELY TO BE LOW COST CARRIERS. NWAC and DAL account for roughly 26% of domestic capacity, which, if trimmed by 7.5% equates to a 2% pt reduction in industry capacity. We believe LCC-heavy routes are likely to see a disproportionate benefit from potential reductions at DAL and NWAC, with AAI, AWA, and JBLU in particular having an easier path for growth. -

Department of Transportation Bureau of Transportation Statistics Office of Airline Information

DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION BUREAU OF TRANSPORTATION STATISTICS OFFICE OF AIRLINE INFORMATION ACCOUNTING AND REPORTING DIRECTIVE No. 328 Issue Date: 10-1-2018 Effective Date: 01-01-2019 Part: 241 Section: 04 AIR CARRIER GROUPINGS This Accounting and Reporting Directive updates the reporting groups for filing the Form 41 report during calendar year 2019 and replaces Reporting Directive No. 325. From our review, the reporting carrier groupings for the carriers below are updated as indicated: AIR CARRIER: NEW REPORTING GROUP: Aloha Air Cargo Group I - $20 million to $100 million to Group II Express Jet Group III to Group II National Airlines Group I - $20 million to $100 million to Group II Republic Group II to Group III SkyLease Group I - $20 million to $100 million to Group II Swift Group I - $20 million to $100 million to Group II Western Global Group I - $20 million to $100 million to Group II Carriers are grouped according to the operating revenue boundaries contained in Section 04 of Part 241. The current reporting levels are: Group III Over $1 billion; Group II Over $100 million to $1 billion; Group I $100 million and under, Subgroups: Group I - $20 million to $100 million, Group I - Under $20 million. Changes in the reporting groups are effective January 1, 2019. Any questions regarding the groupings should be directed to [email protected]. William Chadwick, Jr. Director Office of Airline Information Attachment ATTACHMENT PAGE 1 OF 3 GROUP III AIR CARRIERS - 17 CARRIER Alaska Airlines Allegiant Air American Airlines Atlas Air -

U.S. Department of Transportation Federal

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ORDER TRANSPORTATION JO 7340.2E FEDERAL AVIATION Effective Date: ADMINISTRATION July 24, 2014 Air Traffic Organization Policy Subject: Contractions Includes Change 1 dated 11/13/14 https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/atpubs/CNT/3-3.HTM A 3- Company Country Telephony Ltr AAA AVICON AVIATION CONSULTANTS & AGENTS PAKISTAN AAB ABELAG AVIATION BELGIUM ABG AAC ARMY AIR CORPS UNITED KINGDOM ARMYAIR AAD MANN AIR LTD (T/A AMBASSADOR) UNITED KINGDOM AMBASSADOR AAE EXPRESS AIR, INC. (PHOENIX, AZ) UNITED STATES ARIZONA AAF AIGLE AZUR FRANCE AIGLE AZUR AAG ATLANTIC FLIGHT TRAINING LTD. UNITED KINGDOM ATLANTIC AAH AEKO KULA, INC D/B/A ALOHA AIR CARGO (HONOLULU, UNITED STATES ALOHA HI) AAI AIR AURORA, INC. (SUGAR GROVE, IL) UNITED STATES BOREALIS AAJ ALFA AIRLINES CO., LTD SUDAN ALFA SUDAN AAK ALASKA ISLAND AIR, INC. (ANCHORAGE, AK) UNITED STATES ALASKA ISLAND AAL AMERICAN AIRLINES INC. UNITED STATES AMERICAN AAM AIM AIR REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA AIM AIR AAN AMSTERDAM AIRLINES B.V. NETHERLANDS AMSTEL AAO ADMINISTRACION AERONAUTICA INTERNACIONAL, S.A. MEXICO AEROINTER DE C.V. AAP ARABASCO AIR SERVICES SAUDI ARABIA ARABASCO AAQ ASIA ATLANTIC AIRLINES CO., LTD THAILAND ASIA ATLANTIC AAR ASIANA AIRLINES REPUBLIC OF KOREA ASIANA AAS ASKARI AVIATION (PVT) LTD PAKISTAN AL-AAS AAT AIR CENTRAL ASIA KYRGYZSTAN AAU AEROPA S.R.L. ITALY AAV ASTRO AIR INTERNATIONAL, INC. PHILIPPINES ASTRO-PHIL AAW AFRICAN AIRLINES CORPORATION LIBYA AFRIQIYAH AAX ADVANCE AVIATION CO., LTD THAILAND ADVANCE AVIATION AAY ALLEGIANT AIR, INC. (FRESNO, CA) UNITED STATES ALLEGIANT AAZ AEOLUS AIR LIMITED GAMBIA AEOLUS ABA AERO-BETA GMBH & CO., STUTTGART GERMANY AEROBETA ABB AFRICAN BUSINESS AND TRANSPORTATIONS DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF AFRICAN BUSINESS THE CONGO ABC ABC WORLD AIRWAYS GUIDE ABD AIR ATLANTA ICELANDIC ICELAND ATLANTA ABE ABAN AIR IRAN (ISLAMIC REPUBLIC ABAN OF) ABF SCANWINGS OY, FINLAND FINLAND SKYWINGS ABG ABAKAN-AVIA RUSSIAN FEDERATION ABAKAN-AVIA ABH HOKURIKU-KOUKUU CO., LTD JAPAN ABI ALBA-AIR AVIACION, S.L. -

PORTLAND INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT (PDX) Monthly Traffic Report June, 2019: Fiscal Year Report

PORTLAND INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT (PDX) Monthly Traffic Report June, 2019: Fiscal Year Report This Month Fiscal Year to Date 2019 2018 %Chg 2019 2018 %Chg Total PDX Flight Operations * 21,711 21,200 2.4% 235,278 230,657 2.0% Military 369 215 71.6% 4,293 3,682 16.6% General Aviation 2,146 1,720 24.8% 17,074 16,535 3.3% Hillsboro Airport Operations 12,121 19,758 -38.7% 188,728 204,604 -7.8% Troutdale Airport Operations 12,375 13,498 -8.3% 114,420 127,483 -10.2% Total System Operations 46,207 54,456 -15.1% 538,426 562,744 -4.3% PDX Commercial Flight Operations ** 17,920 18,544 -3.4% 204,160 201,836 1.2% Cargo 1,568 1,708 -8.2% 21,806 21,030 3.7% Charter 4 0 36 20 80.0% Major 9,582 10,000 -4.2% 109,470 106,680 2.6% National 408 484 -15.7% 4,818 6,500 -25.9% Regional 6,358 6,352 0.1% 68,030 67,606 0.6% Domestic 17,082 17,690 -3.4% 195,960 194,082 1.0% International 838 854 -1.9% 8,200 7,754 5.8% Total Enplaned & Deplaned Passengers 1,860,276 1,888,308 -1.5% 19,941,424 19,480,857 2.4% Charter 134 0 884 841 5.1% Major 1,368,081 1,400,967 -2.3% 14,896,381 14,333,240 3.9% National 67,548 77,427 -12.8% 785,557 1,003,840 -21.7% Regional 424,513 409,914 3.6% 4,258,602 4,142,936 2.8% Total Enplaned Passengers 935,016 946,687 -1.2% 9,966,798 9,733,011 2.4% Total Deplaned Passengers 925,260 941,621 -1.7% 9,974,626 9,747,846 2.3% Total Domestic Passengers 1,767,588 1,796,567 -1.6% 19,094,789 18,683,193 2.2% Total Enplaned Passengers 886,446 899,212 -1.4% 9,546,855 9,337,800 2.2% Total Deplaned Passengers 881,142 897,355 -1.8% 9,547,934 9,345,393 2.2% Total