Indigenous Language Programs in South Australian Schools: Issues, Dilemmas and Solutions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Knowledge for Country

2 2 STRENGTHENING OUR KNOWLEDGE FOR COUNTRY Authors: 2.1 INTRODUCTION TO CARING FOR COUNTRY 22 Barry Hunter, Aunty Shaa Smith, Neeyan Smith, Sarah Wright, Paul Hodge, Lara Daley, Peter Yates, Amelia Turner, 2.2 LISTENING AND TALKING WITH COUNTRY 23 Mia Mulladad, Rachel Perkins, Myf Turpin, Veronica Arbon, Eleanor McCall, Clint Bracknell, Melinda McLean, Vic 2.3 SINGING AND DANCING OUR COUNTRY 25 McGrath, Masigalgal Rangers, Masigalgal RNTBC, Doris 2.4 ART FOR COUNTRY 28 Yethun Burarrwaŋa, Bentley James, Mick Bourke, Nathan Wong, Yiyili Aboriginal Community School Board, John Hill, 2.5 BRINGING INDIGENOUS Wiluna Martu Rangers, Birriliburu Rangers, Kate Cherry, Darug LANGUAGES INTO ALL ASPECTS OF LIFE 29 Ngurra, Uncle Lex Dadd, Aunty Corina Norman-Dadd, Paul Glass, Paul Hodge, Sandie Suchet-Pearson, Marnie Graham, 2.6 ESTABLISHING CULTURAL Rebecca Scott, Jessica Lemire, Harriet Narwal, NAILSMA, KNOWLEDGE DATABASES AND ARCHIVES 35 Waanyi Garawa, Rosemary Hill, Pia Harkness, Emma Woodward. 2.7 BUILDING STRENGTH THROUGH KNOWLEDGE-RECORDING 36 2.8 WORKING WITH OUR CULTURAL HIGHLIGHTS HERITAGE, OBJECTS AND SITES 43 j Our Role in caring for Country 2.9 STRENGTHENING KNOWLEDGE j The importance of listening and hearing Country WITH OUR KIDS IN SCHOOLS 48 j The connection between language, songs, dance 2.10 WALKING OUR COUNTRY 54 and visual arts and Country 2.11 WALKING COUNTRY WITH j The role of Indigenous women in caring WAANYI GARAWA 57 for Country 2.12 LESSONS TOWARDS BEST j Keeping ancient knowledge for the future PRACTICE FROM THIS CHAPTER 60 j Modern technology in preserving, protecting and presenting knowledge j Unlocking the rich stories that our cultural heritage tell us about our past j Two-ways science ensuring our kids learn and grow within two knowledge systems – Indigenous and western science 21 2 STRENGTHENING OUR KNOWLEDGE FOR COUNTRY 2.1 INTRODUCTION TO CARING We do many different actions to manage and look after Country9,60,65,66. -

Noun Phrase Constituency in Australian Languages: a Typological Study

Linguistic Typology 2016; 20(1): 25–80 Dana Louagie and Jean-Christophe Verstraete Noun phrase constituency in Australian languages: A typological study DOI 10.1515/lingty-2016-0002 Received July 14, 2015; revised December 17, 2015 Abstract: This article examines whether Australian languages generally lack clear noun phrase structures, as has sometimes been argued in the literature. We break up the notion of NP constituency into a set of concrete typological parameters, and analyse these across a sample of 100 languages, representing a significant portion of diversity on the Australian continent. We show that there is little evidence to support general ideas about the absence of NP structures, and we argue that it makes more sense to typologize languages on the basis of where and how they allow “classic” NP construal, and how this fits into the broader range of construals in the nominal domain. Keywords: Australian languages, constituency, discontinuous constituents, non- configurationality, noun phrase, phrase-marking, phrasehood, syntax, word- marking, word order 1 Introduction It has often been argued that Australian languages show unusual syntactic flexibility in the nominal domain, and may even lack clear noun phrase struc- tures altogether – e. g., in Blake (1983), Heath (1986), Harvey (2001: 112), Evans (2003a: 227–233), Campbell (2006: 57); see also McGregor (1997: 84), Cutfield (2011: 46–50), Nordlinger (2014: 237–241) for overviews and more general dis- cussion of claims to this effect. This idea is based mainly on features -

Guide to Sound Recordings Collected by Luise Hercus 1976-1978

Finding aid HERCUS_L28 Sound recordings collected by Luise Hercus, 1976-1978 Prepared January 2012 by CC Last updated 2 December 2016 ACCESS Availability of copies Listening copies are available. Contact the AIATSIS Audiovisual Access Unit by completing an online enquiry form or phone (02) 6261 4212 to arrange an appointment to listen to the recordings or to order copies. Restrictions on listening Some materials in this collection are restricted and may only be listened to by those who have obtained permission from Luise Hercus as well as the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community. Refer to audition sheets below for more details. Restrictions on use Copies of this collection may be made for private research. Permission must be sought from the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community for any publication or quotation of this material. Any publication or quotation must be consistent with the Copyright Act (1968). SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE Date: 1976-1978 Extent: 43 sound tape reels (ca. 60 min. each) : analogue, mono ; 5 in. Production history These recordings were collected by Luise Hercus in between July 1976 and February 1978 funded by an AIAS (now AIATSIS) grant to study languages collected by interviewees in North East South Australia and Wilcannia, New South Wales. The interviewees are Alice Oldfield, Mona (Merna) Merrick, Elsie Bowman, Ernie Ellis, Brian Marks, Arthur Warren, Ben Murray, Maudie Reese (nee Lennie) and George Macumba who provided the South Australian languages of Arabana, Kuyani, Wangkangurru and Diyari during which references were made to and influences noted from Central Desert languages. Gertie Johnson and Elsie Jones provided Paakantyi material language from NSW; and Jack Long provided Madhi Madhi, Nari Nari, Dadi Dadi language material from NSW and Victoria. -

DS Ang TERRICHE Abdallaha

People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria Ministry of Higher Education and Scentific Research Djillali Liabes University of Sidi Bel Abbes Faculty of Letters, Languages and Arts Department of English Language Planning and Endangered Minority Languages Schools as Agents for Language Revival in Algeria and Australia Thesis Submitted to the Department of English in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctorate in Language Planning and Education Submitted by: Supervised by: Mr. Terriche Abdallah Amin Prof. Melouk Mohamed Board of Examiners Prof. Bedjaoui Fewzia President Sidi Bel Abbes University Prof. Melouk Mohamed Supervisor Sidi Bel Abbes University Prof. Ouerrad Belabbas Examiner Sidi Bel Abbes University Dr. Bensafa Abdelakader Examiner Tlemcen University Dr. Baraka Abdellah Examiner Mascara University Dr. Gambaza Hichem Examiner Saida University 2019-2020 Dedication To all my teachers and teacher educators I Acknowledgements The accomplishment of the present study is due to the assistance of several individuals. I would like to take this opportunity to express immense gratitude to all of them. In particular, I am profoundly indebted to my supervisor, Prof. Melouk Mohamed, who has been very generous with his time, knowledge and assisted me in each step to complete the dissertation. I also owe a debt of gratitude to all members of the jury for their extensive advice and general support: Prof. Bedjaoui Fewzia as president, Prof. Ouerrad Belabbas, Dr. Bensafa Abdelakaer, Dr. Baraka Abdellah, and Dr. Gambaza Hichem as examiners. I gratefully acknowledge the very generous support of Mr Zaitouni Ali, Mr Hamza Mohamed, Dr Robert Amery, and Mr Greg Wilson who were instrumental in producing this work, in particular data collection. -

See Also Kriol

Index A 125, 127, 133–34, 138, 140, 158–59, 162–66, 168, 171, 193, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander 214, 218, 265, 283, 429. Commission (ATSIC) 107, 403, case studies 158 405 Dharug 182, 186–87 Training Policy Statement 2004–06 Miriwoong 149 170 Ngarrindjeri 396 Aboriginal Education Consultative Group Wergaia 247 (AECG) xiii, xviii, 69, 178, 195, Wiradjuri 159, 214, 216–18, 222–23 205 adverbs 333, 409, 411 Dubbo 222 Alphabetic principle 283–84 Aboriginal Education Officers (AEOs) Anaiwan (language) 171 189, 200, 211, 257 Certificate I qualification 171 Aboriginal English xix, 6, 9, 15–16, 76, Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara 91, 147, 293, 303, 364, 373, 383. (APY) 86. See also Pitjantjatjara See also Kriol (language) Aboriginal Land Rights [Northern Territory] Arabana (language) 30 Act 228, 367 language program 30 Aboriginal Languages of Victoria Re- See source Portal (ALV-RP) 310, 315, archival records. language source 317, 320 materials portal architecture 317–319 Arrernte (language) 84–85 Victorian Word Finder 316 Arwarbukarl Cultural Resource Associa- See also Aboriginal Languages Summer School tion (ACRA) 359. Miro- 108, 218 maa Language Program Aboriginal Resource Development Ser- Aboriginal training agency 359 vices (ARDS) xxix workshops 359 absolutive case 379 Audacity sound editing software 334, accusative case 379 393 adjectives audio recordings 29–30, 32, 56, 94, 96, Gamilaraay 409, 411 104, 109–11, 115–16, 121, 123– Ngemba 46 26, 128, 148, 175, 243–44, 309, Wiradjuri 333 316, 327–28, 331–32, 334–35, Yuwaalaraay 411 340, 353, 357–59, 368, 375, 388, See also Adnyamathanha (language) 57 403, 405, 408, 422. -

A Needs-Based Review of the Status of Indigenous Languages in South Australia

“KEEP THAT LANGUAGE GOING!” A Needs-Based Review of the Status of Indigenous Languages in South Australia A consultancy carried out by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission, South Australia by Patrick McConvell, Rob Amery, Mary-Anne Gale, Christine Nicholls, Jonathan Nicholls, Lester Irabinna Rigney and Simone Ulalka Tur May 2002 Declaration The authors of this report wish to acknowledge that South Australia’s Indigenous communities remain the custodians for all of the Indigenous languages spoken across the length and breadth of this state. Despite enormous pressures and institutionalised opposition, Indigenous communities have refused to abandon their culture and languages. As a result, South Australia is not a storehouse for linguistic relics but remains the home of vital, living languages. The wisdom of South Australia’s Indigenous communities has been and continues to be foundational for all language programs and projects. In carrying out this project, the Research Team has been strengthened and encouraged by the commitment, insight and linguistic pride of South Australia’s Indigenous communities. All of the recommendations contained in this report are premised on the fundamental right of Indigenous Australians to speak, protect, strengthen and reclaim their traditional languages and to pass them on to future generations. * Within this report, the voices of Indigenous respondents appear in italics. In some places, these voices stand apart from the main body of the report, in other places, they are embedded within sentences. The decision to incorporate direct quotations or close paraphrases of Indigenous respondent’s view is recognition of the importance of foregrounding the perspectives and aspirations of Indigenous communities across the state. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-17886-1 — the Cambridge World History of Lexicography Edited by John Considine Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-17886-1 — The Cambridge World History of Lexicography Edited by John Considine Index More Information Index Aa (Mesopotamian sign list), 31, 34 academies as producers of dictionaries, 304–5, Aasen, Ivar, 476, 738 311, 313, 418, 428, 433–4, 437, 451, 453–4, 461, Abba–Ababus, 270, 273 466–7, 472–3, 474, 481, 486, 487–8, 531, 541, ‘ ı 242 738 543 545–6 548–9 551–2 Abd-al-lat˙¯f ibni Melek, , , , , ‘Abd-al-Rash¯d,ı 234, 739; see also Farhang-i Accius, 90 Rash¯dı ¯ı Achagua language, 556, 706 Abdel-Nour, Jabbour, 425, 739 Adam von Rottwil, 299 Abenaki language, 599, 706 Addison, Joseph, 486, 489, 517 Abhidha¯nappad¯pika¯ı , 77, 78, 143–5 Addy, Sidney Oldall, 512–13, 739 Abhima¯nacihna, 141 Adelung, Johann Christoph, 462–4, 466, 468, Abramovic´,Teodor, 730, 739 469, 470, 739 ı ı 231 739 abridged dictionaries, Ad¯b Nat˙anz¯, , Arabic, 174, 423, 425, 429 Adler, Ada, 254, 258 Chinese, 204, 214 Aelius Herodianus. See Herodian English, 308, 490–1, 498 Aelius Stilo, 90–1 French, 534, 535 Aeschylus, 257 Greek, 96, 99, 251, 257, 263, 297, 298 Afghā nī navī s, ʻAbdullā h, 387 Hebrew, 188 Afranius, 90, 91 Italian, 538 Afrikaans language, 480–1, 528, 679, 706 Japanese, 619 Afroasiatic languages, 706 Korean, 220 Aggavaṃsa, 76, 144, 739 Latin, 90, 269, 271, 272, 275, Ahom language, 404, 706 284, 286 Aitken, Adam Jack, 514, 739 Persian, 385 Ajayapa¯la, 134, 139, 141, 739 545 149 153 155 645 Portuguese, Akara¯ti Nikan˙˙tu, , , , Scots, 514 Akkadian language, 11–35, 40 Spanish, 541 Aktunç, Hulkı, 375, 739 Tibetan, 147 Albanian -

5 Is It Really a Placename?

5 IS IT REALLY A PLACENAME? Luise Hercus There are few topics as challenging as the study of Australian placenames. Their fODnation varies from region to region, they may be analysable or not, they may refer to the actions of Ancestors, they may be descriptive, or 'indirectly' descriptive: an Ancestor is said to have noticed some particular feature and named the place accordingly. That feature mayor may not be penuanent. Placenames may be single morphemes or consist of a whole sentence, they may show archaic features. In any case they are unpredictable: we can never guess what a place was called. We can also never be sure we are right about a placename unless there is clear evidence stemming from people who have traditional infonuation on the topic. In the absence of such evidence we have to admit we are only guessing. While, for instance, within the bounds of grammatical rules one can know with reasonable surety how to make certain verb fonus, with placenames there are no such bounds; the only limitation is the extent of human imagination. That is why, in those cases where there is clear evidence, they can tell us so much about how people thought about their country. This paper is intended to illustrate this from two specific angles, the use ofgeneric terms as names, and the use ofapparently 'silly' names.' I GENERIC TERMS' If we look at general dictionaries of the past, rather than just placenames, there are many instances of the use of general tenus where one might have expected a specific tenu. -

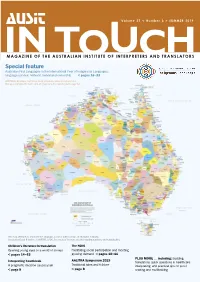

Special Feature

Volume 27 < Number 3 > SUMMER 2019 MAGAZINE OF THE AUSTRALIAN INSTITUTE OF INTERPRETERS AND TRANSLATORS Special feature Australian First Languages in the International Year of Indigenous Languages: language survival, retrieval, revival and ownership < pages 16–22 WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are warned that this issue contains the name and an image of a deceased person: page 18. This map attempts to represent the language, social or nation groups of Aboriginal Australia. Created by David R Horton, © AIATSIS, 1996. See overleaf for more details, including purchase and reproduction. Children’s literature-in-translation The NDIS Opening young eyes to a world of stories Facilitating social participation and meeting < pages 14–15 growing demand < pages 10–11 PLUS MORE … including: budding AALITRA Symposium 2019 Interpreting heartbreak translators; quick questions in healthcare A pragmatic decision causes pain Traditional tales and folklore interpreting; and practical tips on proof- < page 9 < page 8 reading and multitasking < In Touch Summer 2019 Volume 27 number 3 The submission deadline for the Autumn 2020 issue is 1 February Vale Marika Bisas OAM Publication editor Helen Sturgess AUSIT sadly notes the passing of Marika Bisas Callout for [email protected] OAM, a strong and passionate advocate for the T&I profession. An article on Marika's life and her T&I editor contributions to profession, community and family proofers will appear in the April issue of In Touch. Melissa McMahon [email protected] You may have noticed -

And Still They Speak Diyari: the Life History of an Endangered Language

And still they speak Diyari: the life history of an endangered language Peter K. Austin Department of Linguistics SOAS University of London [email protected] SOMMARIO La lingua diyari era parlata tradizionalmente nell’estremo nord dello stato della South Australia, ed ha una storia interessante e complessa nota fin dal 1860, quando venne conosciuta per la prima volta da non aborigeni. Fu utilizzata per attività missionarie luterane dal 1867 al 1914, che portarono allo sviluppo di un suo uso scritto ed alla produzione di testi redatti da parlanti nativi. Ma la sua vitalità venne gravemente colpita dalla chiusura della missione nel 1914. La ricerca linguistica è iniziata nel 1960, e questa lingua è relativamente ben documentata con testi e registrazioni audio. Dal 1990 attività sociali e culturali della comunità hanno prodotto un interesse crescente per il diyari, e una serie di iniziative miranti alla sua rivitalizzazione sono state avviate a partire dal 2008. Diversamente da quanto scritto da alcuni, questa lingua non è estinta, ed ha attualmente diversi parlanti che la parlano con diversi gradi di competenza. Un attivo gruppo di componenti della comunità diyari nutre un forte interesse per la sua conservazione e la sua ripresa. Keywords: endangered language, language revitalisation, Australian Aboriginal languages, Diyari, South Australia ISO 639-3 code: dif Peter K. Austin 1. Introduction1 According to the sixteenth edition of the online language listing Ethnologue (Lewis 2009)2, the Diyari language3 (ISO 639-3 code dif) that was traditionally spoken in the far north of South Australia (see Map 1 below) is categorized as ‘extinct’ and ‘the language is no longer used and no one retains a sense of ethnic identity associated with the language’4. -

Guide to Sound Recordings Collected by Ken Hale, 1958-1960

Finding aid HALE_K06 Sound recordings collected by Ken Hale, 1958-1960 Prepared November 2014 by SL Last updated 8 December 2017 ACCESS Availability of copies Listening copies are available. Contact the AIATSIS Audiovisual Access Unit by completing an online enquiry form or phone (02) 6261 4212 to arrange an appointment to listen to the recordings or to order copies. Restrictions on listening This collection is open for listening. Restrictions on use Copies of this collection may be made for private research. Permission must be sought from the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community for any publication or quotation of this material. Any publication or quotation must be consistent with the Copyright Act (1968). SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE Date: 1958-1960 Extent: 124 audiotape reels ; 5 in. 2 audiotape reels ; 10 1/2 in. Production history These recordings were collected 1958 1nd 1960 by linguist Ken Hale during fieldwork in Gunbalanya, NT, Borroloola, NT, Gurungu, NT, Brunette Downs, NT, Anthony Lagoon, NT, Alice Springs, NT, Oodnadatta, SA, Papunya, NT, Roebourne, WA, Areyonga, NT, Yuendumu, NT, Warrabri, NT, Bidyadanga, WA, Nicholson, WA, Wave Hill, NT, Tennant Creek, NT, Barrow Creek, NT, Murray Downs, NT, Hermannsburg, NT, Santa Teresa, NT, Bond Springs, NT, Port Augusta, NT, Dajarra, Qld, Woree, Qld, Cooktown, Qld, Mitchell River, Qld, Yarrabah, Qld, Holroyd, Qld, Aurukun, Qld, Portland Roads, Qld, Weipa, Qld and Normanton, Qld. The purpose of the field trips was to document the languages and occasionally songs of Indigenous peoples of these areas. The language groups of the speakers and performers are indicated in parentheses after their names. -

Issue 55, December 2013 a Publication of South Australian Native Title Services

Aboriginal Way Issue 55, December 2013 A publication of South Australian Native Title Services Wangki Peel with Clem Lawrie and the Bryant family performing the welcome to country ceremony at the Far West Coast Consent Determination. Far West Coast native title claim resolved The state’s largest native title the Far West Coast to have their various our traditional law and practices,” said into one claim in January 2006 after claim was resolved earlier this native title claims determined. Mr Coleman. ten years of mediation. month at a Federal Court hearing Basil Coleman, Far West Coast Traditional Osker Linde, the group’s solicitor, said The determination covers a vast area north of Yalata community. Lands Association Chairperson, said “the fact that their culture is still alive of land between the Western Australian Justice John Mansfield made a “our people have fought and worked and strong is a testament to elders past Border and Tarcoola to the North and Consent Determination over claims hard for a long time for this recognition and present.” around Streaky Bay to the South. from the Far West Coast claim group to and it provided us with the capacity to They’ve had to claim their rights and It includes several Aboriginal Lands Trust recognise native title rights and interests have greater control over our land and interests in land through the Federal holdings such as Yalata and Koonibba in an area of approximately 80,000 communities for future generations.” Court, and after seventeen years of communities, over which exclusive native square kilometres. struggle, this recognition is an event of It gives us credibility and respect in the title rights will be recognised.