Aboriginal History Journal: Volume 9

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Incorporating Indigenous Knowledge in the Care of Threatened Species at Arakwal National Park

Incorporating Indigenous knowledge in the care of threatened species at Arakwal National Park Project 6.2.1 KEY MESSAGES • Scientists, Traditional • We have held planning • Over the past year, this Owners and Park staff and evaluation workshops project has supported are working together to to develop knowledge- a back-to-country manage the Byron Bay sharing protocols, priority workshop for local Orchid (Diuris byronensis) actions and measures Indigenous families, and its clay heath habitat of success to care for cultural burning in Arakwal National Park. these important areas. on the clay heath habitat and community engagement activities. What is the problem being tackled? The endangered Byron Bay Orchid (Diuris byronensis) is unique to Arakwal National Park. The orchid and its endangered clay heath habitat, which is an endangered ecological community, have important conservation and cultural values. Yet these values are threatened by wild fires, weeds, feral animals and the impact of thousands of tourists who visit this region throughout the year. Joint managers at Arakwal need to work together to ensure effective joint management of these important species and areas. Indigenous burning of clay heath was recently carried out for the first time in 30 years. Photo: Arakwal Aboriginal Corporation. Who is involved? Why is this important to the Bundjalung of Byron Bay People (Arakwal)? This project is a collaboration Local Traditional Owners are the Bundjalung of Byron Bay between Bundjalung people interested in the decisions and People (Arakwal) to look after of Byron Bay (Arakwal), outcomes achieved in this the things they think are most Arakwal joint Park Managers, protected area. -

ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY and CULTURE Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc

ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY AND CULTURE Aboriginal History Incorporated Aboriginal History Inc. is a part of the Australian Centre for Indigenous History, Research School of Social Sciences, The Australian National University, and gratefully acknowledges the support of the School of History and the National Centre for Indigenous Studies, The Australian National University. Aboriginal History Inc. is administered by an Editorial Board which is responsible for all unsigned material. Views and opinions expressed by the author are not necessarily shared by Board members. Contacting Aboriginal History All correspondence should be addressed to the Editors, Aboriginal History Inc., ACIH, School of History, RSSS, 9 Fellows Road (Coombs Building), The Australian National University, Acton, ACT, 2601, or [email protected]. WARNING: Readers are notified that this publication may contain names or images of deceased persons. ON TAUNGURUNG LAND SHARING HISTORY AND CULTURE UNCLE ROY PATTERSON AND JENNIFER JONES Published by ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] Available to download for free at press.anu.edu.au ISBN (print): 9781760464066 ISBN (online): 9781760464073 WorldCat (print): 1224453432 WorldCat (online): 1224452874 DOI: 10.22459/OTL.2020 This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press Cover photograph: Patterson family photograph, circa 1904 This edition © 2020 ANU Press and Aboriginal History Inc. Contents Acknowledgements ....................................... vii Note on terminology ......................................ix Preface .................................................xi Introduction: Meeting and working with Uncle Roy ..............1 Part 1: Sharing Taungurung history 1. -

Report to Office of Water Science, Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation, Brisbane

Lake Eyre Basin Springs Assessment Project Hydrogeology, cultural history and biological values of springs in the Barcaldine, Springvale and Flinders River supergroups, Galilee Basin and Tertiary springs of western Queensland 2016 Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation Prepared by R.J. Fensham, J.L. Silcock, B. Laffineur, H.J. MacDermott Queensland Herbarium Science Delivery Division Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation PO Box 5078 Brisbane QLD 4001 © The Commonwealth of Australia 2016 The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence Under this licence you are free, without having to seek permission from DSITI or the Commonwealth, to use this publication in accordance with the licence terms. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the source of the publication. For more information on this licence visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en Disclaimer This document has been prepared with all due diligence and care, based on the best available information at the time of publication. The department holds no responsibility for any errors or omissions within this document. Any decisions made by other parties based on this document are solely the responsibility of those parties. Information contained in this document is from a number of sources and, as such, does not necessarily represent government or departmental policy. If you need to access this document in a language other than English, please call the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS National) on 131 450 and ask them to telephone Library Services on +61 7 3170 5725 Citation Fensham, R.J., Silcock, J.L., Laffineur, B., MacDermott, H.J. -

Ruby Langford Ginibi: Bundjalung Historian, Writer and Educator

Ruby Langford Ginibi: Bundjalung Historian, Writer and Educator Patricia Grimshaw School of Historical and Philosophical Studies University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC. 3010 [email protected] Abstract: The chapter considers the leadership of Ruby Langford Ginibi, whose writings recorded the history of the Bundjalung people of the Northern Rivers Region of New South Wales. She became prominent in national debates on Indigenous issues from the publication in 1988 of her autobiography, Don’t Take Your Love to Town until her death in 2011. Langford Ginibi was an effective voice in the attempt to persuade non-Aboriginal Australians to acknowledge the oppressive character of settler colonialism and its outcome in negative aspects of many Indigenous Australians’ lives in contemporary Australia. Above all, she drove understanding of the precariousness Indigenous peoples’ livelihoods and the social wellbeing of their families when they left impoverished communities to seek waged work in far flung rural and in urban environments. Through her numerous publications, her research, public talks and interviews, Langford Ginibi made a major contribution to Australia that was recognized by numerous prestigious awards and an honorary doctorate. In 2012, a special issue of the Journal of the European Association of Studies on Australia commemorated her achievements. Key words: Aboriginal historians, Aboriginal writers, Indigenous rights, Bundjalung people, human rights, social justice In 1988 a Bundjalung woman, Ruby Langford (later Ruby Langford Ginibi), published her autobiography Don’t Take Your Love to Town to considerable applause, including the Australian Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission’s Award for Literature.1 Encouraged that she had an audience open to the story of the fraught life situations of Indigenous people, Langford Ginibi continued to produce works that informed non-Indigenous Australians about the past experiences of her people until shortly before her death in October 2011. -

Deep Time Dreaming: a Critical Review

NEW: Emerging Scholars in Australian Indigenous Studies Deep Time Dreaming: A Critical Review Natasha Capstick University of Technology Sydney, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, PO Box 123, Ultimo NSW 2017, Australia. [email protected] DOI: https://doi.org/10.5130/nesais.v4i1.1527 In 2017, Nature, the international journal of science, published research that pushed the dawn of human occupation in Australia even further into deep time: an estimated 65,000 years ago (Clarkson et al. 2017). Inevitably, questions were posed about how this discovery might affect not only our understanding of Australia’s Indigenous past, but also the global story of human evolution. Billy Griffiths’ 2018 book, Deep Time Dreaming: Uncovering Ancient Australia, chronicles developments in the field of Aboriginal archaeology from the mid-twentieth century to the current day, and is therefore well-situated to address the possible implications of these new findings. Deep Time Dreaming is an invaluable read due to the way it demonstrates that the study of deep time is not an isolatable pursuit; rather, archaeology is humanistic and often profoundly political, carrying consequences for how we identify and interact with the present. A 370-page work of historical non-fiction naturally runs the risk of becoming dry and uninspiring. To avoid such an outcome, Griffiths adopts an interlude storytelling structure that weaves together ‘miniature biographies’ of the key players in Australia’s archaeological past with a more personal, journalistic account of the author’s own experiences as an informal apprentice working alongside deep time scholars at significant sites all around the country. -

German Lutheran Missionaries and the Linguistic Description of Central Australian Languages 1890-1910

German Lutheran Missionaries and the linguistic description of Central Australian languages 1890-1910 David Campbell Moore B.A. (Hons.), M.A. This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Social Sciences Linguistics 2019 ii Thesis Declaration I, David Campbell Moore, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text and, where relevant, in the Authorship Declaration that follows. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis contains published work and/or work prepared for publication, some of which has been co-authored. Signature: 15th March 2019 iii Abstract This thesis establishes a basis for the scholarly interpretation and evaluation of early missionary descriptions of Aranda language by relating it to the missionaries’ training, to their goals, and to the theoretical and broader intellectual context of contemporary Germany and Australia. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UM l films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UME a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, b^inning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back o f the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy, ffigher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UM l directly to order. UMl A Bell & Howell Infoimation Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Velar-Initial Etyma and Issues in Comparative Pama-Nyungan by Susan Ann Fitzgerald B.A.. University of V ictoria. 1989 VI.A. -

Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia 1788-1930: Sources

Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia 1788-1930: Sources © Ryan, Lyndall; Pascoe, William; Debenham, Jennifer; Gilbert, Stephanie; Richards, Jonathan; Smith, Robyn; Owen, Chris; Anders, Robert J; Brown, Mark; Price, Daniel; Newley, Jack; Usher, Kaine, 2019. The information and data on this site may only be re-used in accordance with the Terms Of Use. This research was funded by the Australian Government through the Australian Research Council, PROJECT ID: DP140100399. http://hdl.handle.net/1959.13/1340762 Colonial Frontier Massacres in Australia 1788-1930: Sources 0 Abbreviations 1 Unpublished Archival Sources 2 Battye Library, Perth, Western Australia 2 State Records of NSW (SRNSW) 2 Mitchell Library - State Library of New South Wales (MLSLNSW) 3 National Library of Australia (NLA) 3 Northern Territory Archives Service (NTAS) 4 Oxley Memorial Library, State Library Of Queensland 4 National Archives, London (PRO) 4 Queensland State Archives (QSA) 4 State Libary Of Victoria (SLV) - La Trobe Library, Melbourne 5 State Records Of Western Australia (SROWA) 5 Tasmanian Archives And Heritage Office (TAHO), Hobart 7 Colonial Secretary’s Office (CSO) 1/321, 16 June, 1829; 1/316, 24 August, 1831. 7 Victorian Public Records Series (VPRS), Melbourne 7 Manuscripts, Theses and Typescripts 8 Newspapers 9 Films and Artworks 12 Printed and Electronic Sources 13 Colonial Frontier Massacres In Australia, 1788-1930: Sources 1 Abbreviations AJCP Australian Joint Copying Project ANU Australian National University AOT Archives of Office of Tasmania -

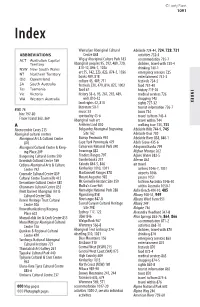

Australia-15-Index.Pdf

© Lonely Planet 1091 Index Warradjan Aboriginal Cultural Adelaide 724-44, 724, 728, 731 ABBREVIATIONS Centre 848 activities 732-3 ACT Australian Capital Wigay Aboriginal Culture Park 183 accommodation 735-7 Territory Aboriginal peoples 95, 292, 489, 720, children, travel with 733-4 NSW New South Wales 810-12, 896-7, 1026 drinking 740-1 NT Northern Territory art 55, 142, 223, 823, 874-5, 1036 emergency services 725 books 489, 818 entertainment 741-3 Qld Queensland culture 45, 489, 711 festivals 734-5 SA South Australia festivals 220, 479, 814, 827, 1002 food 737-40 Tas Tasmania food 67 history 719-20 INDEX Vic Victoria history 33-6, 95, 267, 292, 489, medical services 726 WA Western Australia 660, 810-12 shopping 743 land rights 42, 810 sights 727-32 literature 50-1 tourist information 726-7 4WD 74 music 53 tours 734 hire 797-80 spirituality 45-6 travel to/from 743-4 Fraser Island 363, 369 Aboriginal rock art travel within 744 A Arnhem Land 850 walking tour 733, 733 Abercrombie Caves 215 Bulgandry Aboriginal Engraving Adelaide Hills 744-9, 745 Aboriginal cultural centres Site 162 Adelaide Oval 730 Aboriginal Art & Cultural Centre Burrup Peninsula 992 Adelaide River 838, 840-1 870 Cape York Penninsula 479 Adels Grove 435-6 Aboriginal Cultural Centre & Keep- Carnarvon National Park 390 Adnyamathanha 799 ing Place 209 Ewaninga 882 Afghan Mosque 262 Bangerang Cultural Centre 599 Flinders Ranges 797 Agnes Water 383-5 Brambuk Cultural Centre 569 Gunderbooka 257 Aileron 862 Ceduna Aboriginal Arts & Culture Kakadu 844-5, 846 air travel Centre -

3 Researchers and Coranderrk

3 Researchers and Coranderrk Coranderrk was an important focus of research for anthropologists, archaeologists, naturalists, historians and others with an interest in Australian Aboriginal people. Lydon (2005: 170) describes researchers treating Coranderrk as ‘a kind of ethno- logical archive’. Cawte (1986: 36) has argued that there was a strand of colonial thought – which may be characterised as imperialist, self-congratulatory, and social Darwinist – that regarded Australia as an ‘evolutionary museum in which the primi- tive and civilised races could be studied side by side – at least while the remnants of the former survived’. This chapter considers contributions from six researchers – E.H. Giglioli, H.N. Moseley, C.J.D. Charnay, Rev. J. Mathew, L.W.G. Büchner, and Professor F.R. von Luschan – and a 1921 comment from a primary school teacher, named J.M. Provan, who was concerned about the impact the proposed closure of Coranderrk would have on the ability to conduct research into Aboriginal people. Ethel Shaw (1949: 29–30) has discussed the interaction of Aboriginal residents and researchers, explaining the need for a nuanced understanding of the research setting: The Aborigine does not tell everything; he has learnt to keep silent on some aspects of his life. There is not a tribe in Australia which does not know about the whites and their ideas on certain subjects. News passes quickly from one tribe to another, and they are quick to mislead the inquirer if it suits their purpose. Mr. Howitt, Mr. Matthews, and others, who made a study of the Aborigines, often visited Coranderrk, and were given much assistance by Mr. -

1 Picturing a Golden Age: September and Australian Rules Pauline Marsh, University of Tasmania It Is 1968, Rural Western Austra

1 Picturing a Golden Age: September and Australian Rules Pauline Marsh, University of Tasmania Abstract: In two Australian coming-of-age feature films, Australian Rules and September, the central young characters hold idyllic notions about friendship and equality that prove to be the keys to transformative on- screen behaviours. Intimate intersubjectivity, deployed in the close relationships between the indigenous and nonindigenous protagonists, generates multiple questions about the value of normalised adult interculturalism. I suggest that the most pointed significance of these films lies in the compromises that the young adults make. As they reach the inevitable moral crisis that awaits them on the cusp of adulthood, despite pressures to abandon their childhood friendships they instead sustain their utopian (golden) visions of the future. It is 1968, rural Western Australia. As we glide along an undulating bitumen road up ahead we see, from a low camera angle, a school bus moving smoothly along the same route. Periodically a smattering of roadside trees filters the sunlight, but for the most part open fields of wheat flank the roadsides and stretch out to the horizon, presenting a grand and golden vista. As we reach the bus, music that has hitherto been a quiet accompaniment swells and in the next moment we are inside the vehicle with a fair-haired teenager. The handsome lad, dressed in a yellow school uniform, is drawing a picture of a boxer in a sketchpad. Another cut takes us back outside again, to an equally magnificent view from the front of the bus. This mesmerising piece of cinema—the opening of September (Peter Carstairs, 2007)— affords a viewer an experience of tranquillity and promise, and is homage to the notion of a golden age of youth. -

A STUDY GUIDE by Katy Marriner

© ATOM 2012 A STUDY GUIDE BY KATY MARRINER http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN 978-1-74295-267-3 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au Raising the Curtain is a three-part television series celebrating the history of Australian theatre. ANDREW SAW, DIRECTOR ANDREW UPTON Commissioned by Studio, the series tells the story of how Australia has entertained and been entertained. From the entrepreneurial risk-takers that brought the first Australian plays to life, to the struggle to define an Australian voice on the worldwide stage, Raising the Curtain is an in-depth exploration of all that has JULIA PETERS, EXECUTIVE PRODUCER ALINE JACQUES, SERIES PRODUCER made Australian theatre what it is today. students undertaking Drama, English, » NEIL ARMFIELD is a director of Curriculum links History, Media and Theatre Studies. theatre, film and opera. He was appointed an Officer of the Order Studying theatre history and current In completing the tasks, students will of Australia for service to the arts, trends, allows students to engage have demonstrated the ability to: nationally and internationally, as a with theatre culture and develop an - discuss the historical, social and director of theatre, opera and film, appreciation for theatre as an art form. cultural significance of Australian and as a promoter of innovative Raising the Curtain offers students theatre; Australian productions including an opportunity to study: the nature, - observe, experience and write Australian Indigenous drama. diversity and characteristics of theatre about Australian theatre in an » MICHELLE ARROW is a historian, as an art form; how a country’s theatre analytical, critical and reflective writer, teacher and television pre- reflects and shape a sense of na- manner; senter.