Championing Careers Guidance in Schools: Impact Evaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bexleyheath Academy Woolwich Road, Bexleyheath, DA6 7DA

School report Bexleyheath Academy Woolwich Road, Bexleyheath, DA6 7DA Inspection dates 18−19 September 2013 Previous inspection: Not previously inspected Overall effectiveness This inspection: Good 2 Achievement of pupils Good 2 Quality of teaching Good 2 Behaviour and safety of pupils Good 2 Leadership and management Good 2 Summary of key findings for parents and pupils This is a good school. ‘The Principal is inspirational.’ ‘We are in a The sixth form is good. Students are phase of strong, meaningful and planned successfully guided onto academic and leadership.’ Such feedback from parents, vocational courses they enjoy and succeed in carers and staff highlights the Principal’s and that lead reliably to further education, outstanding ability to engage and encourage. training or employment. With skilled senior leaders, he is raising Systematic monitoring, well-directed training expectations and improving achievement. and effective teacher recruitment are Most students enter with low attainment and extending and embedding good teaching, as make good progress, particularly those in students’ progress shows. need of additional support. Well-evidenced Governors provide expert challenge and checks on current learning indicate that last support, closely monitoring the impact of year’s improvement is being maintained. leadership, teaching and use of government Government targets are met. funding (Year 7 catch-up and pupil premium). The range of subjects on offer reflects Students are keen and respond happily to national trends, extends students’ options challenge. They treat adults and each other and supports their spiritual, moral, cultural considerately, untroubled by differences of and social development. Good use is made of culture or lifestyle. -

England LEA/School Code School Name Town 330/6092 Abbey

England LEA/School Code School Name Town 330/6092 Abbey College Birmingham 873/4603 Abbey College, Ramsey Ramsey 865/4000 Abbeyfield School Chippenham 803/4000 Abbeywood Community School Bristol 860/4500 Abbot Beyne School Burton-on-Trent 312/5409 Abbotsfield School Uxbridge 894/6906 Abraham Darby Academy Telford 202/4285 Acland Burghley School London 931/8004 Activate Learning Oxford 307/4035 Acton High School London 919/4029 Adeyfield School Hemel Hempstead 825/6015 Akeley Wood Senior School Buckingham 935/4059 Alde Valley School Leiston 919/6003 Aldenham School Borehamwood 891/4117 Alderman White School and Language College Nottingham 307/6905 Alec Reed Academy Northolt 830/4001 Alfreton Grange Arts College Alfreton 823/6905 All Saints Academy Dunstable Dunstable 916/6905 All Saints' Academy, Cheltenham Cheltenham 340/4615 All Saints Catholic High School Knowsley 341/4421 Alsop High School Technology & Applied Learning Specialist College Liverpool 358/4024 Altrincham College of Arts Altrincham 868/4506 Altwood CofE Secondary School Maidenhead 825/4095 Amersham School Amersham 380/6907 Appleton Academy Bradford 330/4804 Archbishop Ilsley Catholic School Birmingham 810/6905 Archbishop Sentamu Academy Hull 208/5403 Archbishop Tenison's School London 916/4032 Archway School Stroud 845/4003 ARK William Parker Academy Hastings 371/4021 Armthorpe Academy Doncaster 885/4008 Arrow Vale RSA Academy Redditch 937/5401 Ash Green School Coventry 371/4000 Ash Hill Academy Doncaster 891/4009 Ashfield Comprehensive School Nottingham 801/4030 Ashton -

Candidate Information Brochure

CANDIDATE INFORMATION BROCHURE To inspire young people to make their best better October 2016 Dear Candidate, Thank you for showing an interest in the Teacher of REP role at Tendring Technology College. Tendring Technology College, judged by Ofsted as ‘good’ in all catergories , with the behaviour of students being rated as ‘outstanding’ in March 2016. We opened in August 2011 and are part of Academies Enterprise Trust, the largest nationwide, multi academy sponsor in the country. Academies Enterprise Trust firmly believes that all young people deserve to become world class learners – to learn, enjoy, succeed and thrive in a world class educational environment, which has the best facilities, the best teaching and the most up to date resources available to them. Our vision is to help students achieve world class learning outcomes by developing world class teachers in a world class community. Tendring Technology College has an exciting future and this appointment represents a great opportunity to secure positive outcomes for our learners. If you share our vision and values then we would be very excited to hear from you. Yours faithfully The Recruitment Team Tendring Technology College Tendring Technology College serves a wide catchment area in the Tendring District that is a mix of rural and coastal environment with easy access to the vibrant town of Colchester with London Liverpool Street a straightforward train journey. TTC is unique in that it is a split site College. The Thorpe campus is dedicated to our Key Stage 3 students and nearly 5 miles away is the Frinton campus for our Key Stage 4 and 5 students. -

The PTI Schools Programme and Schools Leadership Programme : Member Schools

The PTI Schools Programme and Schools Leadership Programme : Member Schools (excluding Greater London) Member schools in Greater London East Midlands Subjects in the Schools Member of the Schools School Programme Leadership Programme Ashfield School Modern Foreign Languages Brooke Weston Academy Modern Foreign Languages Brookvale High School Music Caistor Yarborough Academy Maths Yes Carre's Grammar School History Yes Manor High School MFL and Science Yes Monks' Dyke Tennyson College Yes Northampton School for Boys Geography and MFL Sir Robert Pattinson Academy Yes Spalding Grammar School Latin Yes University Academy Holbeach Geography Weavers Academy MFL Art, English, Geography, History, William Farr CE School Yes Maths, MFL, Music and Science Eastern England Subjects in the Schools Member of the Schools School Programme Leadership Programme City of Norwich School History Mathematics and Modern Foreign Coleridge Community College Languages English, History, Art, Music, Davenant Foundation School Science and Modern Foreign Yes Languages Downham Market Academy Yes Harlington Upper School History Hedingham School and Sixth Geography Form Luton Sixth Form College Latin Geography, History, Maths, Monk's Walk School Music, Science and Art Nene Park Academy English Mathematics and Modern Foreign Notre Dame High School Languages Ormiston Sudbury Academy Geography, History and Science Palmer's College English and Science Latin, Science, Mathematics and Parkside Community College Yes Modern Foreign Languages Passmores Academy MFL and Music Saffron -

Candidate Information Brochure

CANDIDATE INFORMATION BROCHURE To inspire young people to make their best better December 2015 Dear Candidate Thank you for taking the time to apply for the 1-1 English Tutor role at New Rickstones Academy. New Rickstones Academy opened in September 2008 and is part of Academies Enterprise Trust, the largest nationwide, multi academy sponsor in the country. The Academies Enterprise Trust firmly believes that all young people deserve to become world class learners – to learn, enjoy, succeed and thrive in a world class educational environment, which has the best facilities, the best teaching and the most up to date resources available to them. Our vision is to help students achieve world class learning outcomes by developing world class teachers in a world class community. New Rickstones Academy has an exciting future and this appointment represents a great opportunity to secure positive outcomes for our learners. If you share our vision and values then we would be very excited to hear from you. Yours sincerely The Recruitment Team New Rickstones Academy At New Rickstones Academy, we are passionate about learning. A creative and dynamic academy, we deliver a broad, balanced, personalised and rigorous education that prepares students for the challenges and opportunities of living and working in the 21st century. New Rickstones Academy has approximately 650 students on roll and has held specialisms in Arts and Maths. In 2013, the academy recorded its best ever results. In February 2012, the academy moved into its new state of the art £25 million building, which provides an outstanding environment for teaching and learning. -

Candidate Information Brochure Aylward Academy

CANDIDATE INFORMATION BROCHURE AYLWARD ACADEMY To inspire young people to make their best better November 2016 Dear Candidate, Thank you for your interest in the Curriculum and Assessment Manager role at Aylward Academy. We are passionate about ensuring that, individually, we are continually improving and challenging ourselves and as an academy, striving towards our vision ‘To make our best better’ and become a great school. Aylward is a community academy based in a deprived area of North London. Since its foundation in 2010 it has dedicated itself to the education of young people from the local area, driving the Value Added score up to 1029. There is now a waiting list for year 7 entrants and the sixth form has grown from 30 to just under 300. The academy opened in 2010 with an Ofsted notice to improve and in an extremely short time were graded good in a 2012 inspection. The most recent inspection conducted in the summer of 2016 confirmed the school continues to be good whilst also identifying outstanding features. In 2012 the Ofsted report confirmed that, “Students are well motivated in their learning and their behaviour is good”. It also stated that, “Teachers plan well- structured lessons in line with students’ abilities and this adds to their enjoyment of learning”. We place learning at the core of everything we do at Aylward Academy. We have a committed and highly skilled staff and Governing Body who are dedicated to ensuring that all students achieve the best possible outcomes in their academic qualifications as well as their personal development. -

Bexleyheath Academy Woolwich Road, Bexleyheath, Kent DA6 7DA

School report Bexleyheath Academy Woolwich Road, Bexleyheath, Kent DA6 7DA Inspection dates 28–29 November 2018 Overall effectiveness Inadequate Effectiveness of leadership and management Inadequate Quality of teaching, learning and assessment Inadequate Personal development, behaviour and welfare Inadequate Outcomes for pupils Inadequate 16 to 19 study programmes Good Overall effectiveness at previous inspection Requires improvement Summary of key findings for parents and pupils This is an inadequate school The school is failing to give its pupils an Pupils’ behaviour is poor, and teachers’ acceptable standard of education. Leaders are expectations are too low. Pupils’ poor not demonstrating the capacity to improve the behaviour disrupts learning and hinders school. progress. Leaders have not taken essential actions to Different groups of pupils, including the most make improvements. Standards have fallen for able and those with special educational needs several years. and/or disabilities (SEND) make progress that is significantly below national averages. Systems developed by the new leadership team to improve the quality of education in the Governors are not thorough enough in how school are recent and have not yet had an they hold leaders to account. They have not impact. Staff do not use the school’s policies ensured that additional funding for special consistently. Teachers do not use assessment educational needs and the pupil premium are information to inform their planning. Pupils used effectively. make weak progress from their starting points. Leaders do not support staff well enough. Staff The curriculum does not meet pupils’ needs. morale is low. Pupils’ learning is disrupted by a Programmes of study in key stage 3 do not high turnover of staff. -

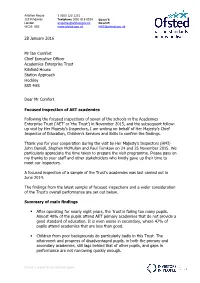

AET Academies

Aviation House T 0300 123 1231 125 Kingsway Textphone 0161 618 8524 Direct T: London [email protected] Direct F: WC2B 6SE www.ofsted.gov.uk [email protected] 28 January 2016 Mr Ian Comfort Chief Executive Officer Academies Enterprise Trust Kilnfield House Station Approach Hockley SS5 4HS Dear Mr Comfort Focused inspection of AET academies Following the focused inspections of seven of the schools in the Academies Enterprise Trust (‘AET’ or ‘the Trust’) in November 2015, and the subsequent follow- up visit by Her Majesty’s Inspectors, I am writing on behalf of Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Education, Children’s Services and Skills to confirm the findings. Thank you for your cooperation during the visit by Her Majesty’s Inspectors (HMI) John Daniell, Stephen McMullan and Paul Tomkow on 24 and 25 November 2015. We particularly appreciate the time taken to prepare the visit programme. Please pass on my thanks to your staff and other stakeholders who kindly gave up their time to meet our inspectors. A focused inspection of a sample of the Trust’s academies was last carried out in June 2014. The findings from the latest sample of focused inspections and a wider consideration of the Trust’s overall performance are set out below. Summary of main findings . After operating for nearly eight years, the Trust is failing too many pupils. Almost 40% of the pupils attend AET primary academies that do not provide a good standard of education. It is even worse in secondary, where 47% of pupils attend academies that are less than good. -

Candidate Information Brochure

CANDIDATE INFORMATION BROCHURE To inspire young people to make their best better September 2016 Dear Candidate, Thank you for taking the time to apply for the Assistant Headteacher role at Lea Forest Primary Academy. Lea Forest Primary Academy opened in December 2012 and is part of Academies Enterprise Trust, the largest nationwide, multi academy sponsor in the country. Academies Enterprise Trust firmly believes that all young people deserve to become world class learners – to learn, enjoy, succeed and thrive in a world class educational environment, which has the best facilities, the best teaching and the most up to date resources available to them. Our vision is to help students achieve world class learning outcomes by developing world class teachers in a world class community. Lea Forest Primary Academy has an exciting future and this appointment represents a great opportunity to secure positive outcomes for our learners. If you share our vision and values then we would be very excited to hear from you. Yours faithfully, The Recruitment Team Lea Forest Primary Academy Lea Forest Primary Academy is a happy, dedicated and enthusiastic academy. We are committed to safeguarding and promoting the well-being and welfare of all of our children and young people and expect all staff and volunteers to share this commitment. We work hard to provide a stimulating environment in which each child can realise their full potential, developing their individual abilities, alongside the acquisition of skills and establishing positive values and attitudes. Lea Forest Primary Academy is a larger than average two form entry community academy that was originally built as two separate buildings over an extensive site in 1938. -

Promoting the Achievement of Looked After Children and Young People In

Institute of Education Promoting the achievement of looked after children and young people in the London Borough of Hounslow May 2017 Case studies of education provision for children and young people in care in the London Borough of Hounslow Promoting the Achievement of Looked After Children PALAC Contents Introduction 4 Case studies 6 Cranford Community College 7 Making lasting changes in school step by step Chiswick School 11 Chiswick Book Club The Green School 16 Corporate Parenting in Practice Kingsley Academy 20 There is no ‘magic bullet’ approach to improving outcomes for children and young people in care West Thames and South Thames Colleges 23 Improving provision for students in care in Further Education Conclusion 26 Authors UCL Institute of Education Gill Brackenbury, Director, Centre for Inclusive Education Dr Catherine Carroll, Senior Research Associate, Centre for Inclusive Education Professor Claire Cameron, Deputy Director, Thomas Coram Research Unit Elizabeth Herbert, Lecturer, Centre for Inclusive Education Dr Amelia Roberts, Deputy Director, Centre for Inclusive Education Hounslow Virtual School Karena Brown Kate Elliott Sue Thompson Schools Chiswick School, Andrea Kitteringham Cranford Community College, Simon Dean Kingsley Academy, Sharon Gladstone and Catherine McCutcheon The Green School for Girls, Francis Markall Acknowledgments The authors would like to thank all the children and young people, their carers, parents, schools and local authority colleagues who have contributed their time and support to the case studies described in this report. 3 Introduction Education of children in care As of March 2016, there were 70,440 However, research is emerging to show that children and young people in care in children and young people in care can have England. -

London Learners, London Lives: Tackling the School

Education Panel London learners, London lives Tackling the school places crisis and supporting children to achieve the best they can September 2014 Education Panel Members Jennette Arnold OBE (Chair) Labour Tony Arbour Conservative Andrew Boff Conservative Andrew Dismore Labour Darren Johnson Green Caroline Pidgeon MBE Liberal Democrat Contact: Richard Derecki email: [email protected] Tel: 020 7983 4899 Cover photo by Sue Harris, Governor Ashburnham Community School. ©Greater London Authority September 2014 2 Contents Foreword 4 Executive Summary 6 1. The school places crisis 8 2. The challenge to raise standards across London’s schools 18 3. Accountability and tackling poorly performing schools 24 4. Developing a regional identity 27 Appendix 1 Recommendations 29 Appendix 2 Endnotes 30 Orders and translations 32 3 Foreword The beating heart of our global city is our education system. Timid, shy, playful four year olds are transformed through primary and secondary school into articulate, creative, resourceful young people who will drive our city forward to ever greater success. At least that is the goal. A good school will achieve that end; supporting and nurturing the development of the child into a young person the city can be proud of. A poor school will quite possibly irreparably damage the life chances of the children entrusted to it. Over the past year I and my colleagues on the Education Panel have been reviewing how London government can effectively respond to two great challenges faced by our education sector: how to ensure we create enough school places to meet the demands from our fast growing population; and how to ensure that our schools continue to stretch the able and support those that need extra support to ensure they all achieve the best they can. -

Minded to Terminate Letter to Bexleyheath Academy

The Members and Trustees Academies Enterprise Trust 3rd Floor, 183 Eversholt Street London NW1 1BU 28 March 2019 Dear Sirs, Minded to Terminate Letter to the Members and Trustees of Academies Enterprise Trust in respect of Bexleyheath Academy In accordance with section 2A of the Academies Act 2010i, any funding agreement of an academy may be terminated by the Secretary of State where special measures are required to be taken by the academy, or the academy requires significant improvement and the Chief Inspector of Ofsted has given notice of that under section 13(3) (a) of the Education Act 2005. We received an Ofsted inspection report dated 7 February 2019 confirming that Bexleyheath Academy was judged inadequate following a section 5 inspection on 28-29 November 2018, and requires special measures. The school was judged ‘Inadequate’ across all measures, apart from 16-19 provision, which was rated as ‘Good’. Of serious concern were Ofsted’s conclusions: The school is failing to give its pupils an acceptable standard of education. Leaders are not demonstrating the capacity to improve the school. Leaders have not taken essential actions to make improvements. Standards have fallen for several years. Systems developed by the new leadership team to improve the quality of education in the school are recent and have not yet had an impact. Staff do not use the school’s policies consistently. Teachers do not use assessment information to inform their planning. Pupils make weak progress from their starting points. The curriculum does not meet pupils’ needs. Programmes of study in key stage 3 do not prepare pupils well enough for key stage 4.