War at Sea: Nineteenth-Century Laws for Twenty-First

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clash of Steel a Closer Look at WWII Grand Strategy Simulation

Clash of Steel A Closer Look at WWII Grand Strategy Simulation Table of Contents Introduction Third Reich vs COS Ground Units Where's the Front? Getting Cutoff Strength, Morale, Efficiency, & Supply Air Units Naval Units Action Points Troop Quality (Efficiency) Ground Combat Weather Supply Railroads Mechanized Infantry Conquering Countries and Victory Points Economies Strategic Bombing Research Politics Grand Strategy Equations Combat Tables Versions Rule Book COS II Why Did I Write This? Introduction The designer of a wargame is confronted with two conflicting goals. One goal is to design a game that is fun to play. The other is to design a game which is reasonably accurate. A little too much of the former and one builds a “beer and pretzels” game; fast and fun at the expensive of realism. A design based on the later often finds its way into the “monster” game hall of fame; big and slow with lots of stats. It is indeed rare when a design emerges which nicely balances the two extremes. The end result is a game which is relatively fast and fun while also embodying solid realistic modeling. SSI's Clash of Steel (COS) is one such game. The purpose of this paper is to highlight some well-designed features of COS. On the surface, COS is a very simple and straight-forward game. However, under the surface one will find a magnificently designed and well thought-out model of WWII grand strategy. It is easy to confuse simplicity with a lack of realism. On the other hand, it is also easy to confuse complexity with accuracy. -

American Naval Policy, Strategy, Plans and Operations in the Second Decade of the Twenty- First Century Peter M

American Naval Policy, Strategy, Plans and Operations in the Second Decade of the Twenty- first Century Peter M. Swartz January 2017 Select a caveat DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A. Approved for public release: distribution unlimited. CNA’s Occasional Paper series is published by CNA, but the opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of CNA or the Department of the Navy. Distribution DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A. Approved for public release: distribution unlimited. PUBLIC RELEASE. 1/31/2017 Other requests for this document shall be referred to CNA Document Center at [email protected]. Photography Credit: A SM-6 Dual I fired from USS John Paul Jones (DDG 53) during a Dec. 14, 2016 MDA BMD test. MDA Photo. Approved by: January 2017 Eric V. Thompson, Director Center for Strategic Studies This work was performed under Federal Government Contract No. N00014-16-D-5003. Copyright © 2017 CNA Abstract This paper provides a brief overview of U.S. Navy policy, strategy, plans and operations. It discusses some basic fundamentals and the Navy’s three major operational activities: peacetime engagement, crisis response, and wartime combat. It concludes with a general discussion of U.S. naval forces. It was originally written as a contribution to an international conference on maritime strategy and security, and originally published as a chapter in a Routledge handbook in 2015. The author is a longtime contributor to, advisor on, and observer of US Navy strategy and policy, and the paper represents his personal but well-informed views. The paper was written while the Navy (and Marine Corps and Coast Guard) were revising their tri- service strategy document A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower, finally signed and published in March 2015, and includes suggestions made by the author to the drafters during that time. -

Technology Strategy Integration

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Calhoun, Institutional Archive of the Naval Postgraduate School Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 2012-06 Technology Strategy Integration Carter, Keith L. Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/7317 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS TECHNOLOGY STRATEGY INTEGRATION by Keith L. Carter June 2012 Thesis Advisor: John Arquilla Second Reader: Doowan Lee Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704–0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202–4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704–0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED June 2012 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE Technology Strategy Integration 5. FUNDING NUMBERS 6. AUTHOR(S) Keith L. Carter 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION Naval Postgraduate School REPORT NUMBER Monterey, CA 93943–5000 9. SPONSORING /MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. -

The Boardgamer Magazine

Volume 9, Issue 3 July 2004 The BOARDGAMER Sample file Dedicated To The Competitive Play of Avalon Hill / Victory Games and the Board & Card Games of the World Boardgame Championships Featuring: Puerto Rico, 1776, Gunslinger, Victory In The Pacific, Naval War, Panzerblitz / Panzer Leader and AREA Ratings 2 The Boardgamer Volume 9, Issue 3 July 2004 Current Specific Game AREA Ratings To have a game AREA rated, report the game result to: Glenn Petroski; 6829 23rd Avenue; Kenosha, WI 53143-1233; [email protected] March Madness War At Sea Roborally 48 Active Players Apr. 12, 2004 134 Active Players Apr. 1, 2004 70 Active Players Feb. 9, 2004 1. Bruce D Reiff 5816 1. Jonathan S Lockwood 6376 1. Bradley Johnson 5439 2. John Coussis 5701 2. Ray Freeman 6139 2. Jeffrey Ribeiro 5187 3. Kenneth H Gutermuth Jr 5578 3. Bruce D Reiff 6088 3. Patrick Mitchell 5143 4. Debbie Gutermuth 5532 4. Patrick S Richardson 6042 4. Clyde Kruskal 5108 5. Derek Landel 5514 5. Kevin Shewfelt 6036 5. Winton Lemoine 5101 6. Peter Staab 5489 6. Stephen S Packwood 5922 6. Marc F Houde 5093 7. Stuart K Tucker 5398 7. Glenn McMaster 5887 7. Brian Schott 5092 8. Steven Caler 5359 8. Michael A Kaye 5873 8. Jason Levine 5087 9. David Anderson 5323 9. Andy Gardner 5848 9. David desJardins 5086 10. Dennis D Nicholson 5295 10. Nicholas J Markevich 5770 10. James M Jordan 5080 11. Harry E Flawd III 5248 11. Vince Meconi 5736 11. Kaarin Engelmann 5078 12. Bruno Passacantando 5236 12. -

The Provision of Naval Defense in the Early American Republic a Comparison of the U.S

SUBSCRIBE NOW AND RECEIVE CRISIS AND LEVIATHAN* FREE! “The Independent Review does not accept “The Independent Review is pronouncements of government officials nor the excellent.” conventional wisdom at face value.” —GARY BECKER, Noble Laureate —JOHN R. MACARTHUR, Publisher, Harper’s in Economic Sciences Subscribe to The Independent Review and receive a free book of your choice* such as the 25th Anniversary Edition of Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government, by Founding Editor Robert Higgs. This quarterly journal, guided by co-editors Christopher J. Coyne, and Michael C. Munger, and Robert M. Whaples offers leading-edge insights on today’s most critical issues in economics, healthcare, education, law, history, political science, philosophy, and sociology. Thought-provoking and educational, The Independent Review is blazing the way toward informed debate! Student? Educator? Journalist? Business or civic leader? Engaged citizen? This journal is for YOU! *Order today for more FREE book options Perfect for students or anyone on the go! The Independent Review is available on mobile devices or tablets: iOS devices, Amazon Kindle Fire, or Android through Magzter. INDEPENDENT INSTITUTE, 100 SWAN WAY, OAKLAND, CA 94621 • 800-927-8733 • [email protected] PROMO CODE IRA1703 The Provision of Naval Defense in the Early American Republic A Comparison of the U.S. Navy and Privateers, 1789–1815 F NICHOLAS J. ROSS he War of 1812 began badly for British ocean-going commerce. Although the United States had a pitifully small navy, it did have a large merchant T marine fleet keen to make a profit. Shortly after the outbreak of the war, the London Times lamented, “American merchant seamen were almost to a man con- verted into privateersmen and the whole of our West India trade either has or will in consequence sustain proportionate loss” (Letters from New York State 1812). -

Guide to the War of 1812 Sources

Source Guide to the War of 1812 Table of Contents I. Military Journals, Letters and Personal Accounts 2 Service Records 5 Maritime 6 Histories 10 II. Civilian Personal and Family Papers 12 Political Affairs 14 Business Papers 15 Histories 16 III. Other Broadsides 17 Maps 18 Newspapers 18 Periodicals 19 Photos and Illustrations 19 Genealogy 21 Histories of the War of 1812 23 Maryland in the War of 1812 25 This document serves as a guide to the Maryland Center for History and Culture’s library items and archival collections related to the War of 1812. It includes manuscript collections (MS), vertical files (VF), published works, maps, prints, and photographs that may support research on the military, political, civilian, social, and economic dimensions of the war, including the United States’ relations with France and Great Britain in the decade preceding the conflict. The bulk of the manuscript material relates to military operations in the Chesapeake Bay region, Maryland politics, Baltimore- based privateers, and the impact of economic sanctions and the British blockade of the Bay (1813-1814) on Maryland merchants. Many manuscript collections, however, may support research on other theaters of the war and include correspondence between Marylanders and military and political leaders from other regions. Although this inventory includes the most significant manuscript collections and published works related to the War of 1812, it is not comprehensive. Library and archival staff are continually identifying relevant sources in MCHC’s holdings and acquiring new sources that will be added to this inventory. Accordingly, researchers should use this guide as a starting point in their research and a supplement to thorough searches in MCHC’s online library catalog. -

War at Sea Class Limits

War at Sea Class Limits Australia (RAN) Aviation Units; NL} A-29 Kittyhawk (Set A) RAF--RCAF--RAAF--RNZAF--USAAF--Russia NL} DAP Beaufort Mk. VIII (Set B) RAAF--R NL} DAP Beaufighter Mk.21 (Set D) RCAF--RAF--RAAF--RNZAF--USAAF Cruisers; 3} Australia (Set 5) Canberra (Set 1) Shropshire (Set D) ** County class [Kent] 1} Adelaide (Set C) ** WW1 Town class 3} Sydney (Set 1), Perth (Set B) + Hobart ** Amphion class [modified Leander] Destroyers; NL} Stuart (Set D) ** Scott class [6 WW2] 3} Arunta (Set 2) + Warramunga, Bataan ** Tribal class [Cossack] 4} Vampire (Set A) + Vendetta, + Waterhen + Voyager ** WW1 V-W Class 5} Nizam (Starter) + Napier, Nepal, Nestor, Norman ** J-K-N class [Javelin] New Zealand (RNZN) Cruisers; 2} Leander (Set 3) + Achilles ** Leander class 1} Gambia (Set B) ** Colony class [Jamaica] Norway (RNoN) Cruisers; 2} Norge (Set D) + Eidsvold Destroyers; 2} Stord (Set C) + Svenner ** S-T class [Saumarez] Submarines; 2} Ula (Set C ) + Uredd ** UK U-class Fortress; 1} Oscarsborg (Set D) Canada (RCN) Aviation Units; NL} Hudson Mk III (Set B) RAF--RNZAF--RCAF--USAAF--RAAF Cruisers; 1} Uganda (Set 4) ** Colony class [Jamaica] 1} Ontario (Set D) ** Swiftsure class Destroyers; 2} Saguenay (Set C) + Skeena ** A-B class 2} Algonquin ( Set 6) + Sioux ** U-V class NL} Haida (Set 2) 4 in RCN ** Tribal class [Cossack] NL} St. Laurent (Set 5) 7 in RCN ** C-D class NL} Sackville (Set 3) 107 in RCN ** Flower class Auxiliaries; 3} Prince David (Set A) + Prince Robert and Prince Henry Greece (BN) Aviation Units; NL} Bloch MB. -

Download the Full PDF Here

THE PHILADELPHIA PAPERS A Publication of the Foreign Policy Research Institute GREAT WAR AT SEA: REMEMBERING THE BATTLE OF JUTLAND by John H. Maurer May 2016 13 FOREIGN POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE THE PHILADELPHIA PAPERS, NO. 13 GREAT WAR AT SEA: REMEMBERING THE BATTLE OF JUTLAND BY JOHN H. MAURER MAY 2016 www.fpri.org 1 THE PHILADELPHIA PAPERS ABOUT THE FOREIGN POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE Founded in 1955 by Ambassador Robert Strausz-Hupé, FPRI is a non-partisan, non-profit organization devoted to bringing the insights of scholarship to bear on the development of policies that advance U.S. national interests. In the tradition of Strausz-Hupé, FPRI embraces history and geography to illuminate foreign policy challenges facing the United States. In 1990, FPRI established the Wachman Center, and subsequently the Butcher History Institute, to foster civic and international literacy in the community and in the classroom. ABOUT THE AUTHOR John H. Maurer is a Senior Fellow of the Foreign Policy Research Institute. He also serves as the Alfred Thayer Mahan Professor of Sea Power and Grand Strategy at the Naval War College in Newport, Rhode Island. The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone, and do not represent the settled policy of the Naval War College, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. Foreign Policy Research Institute 1528 Walnut Street, Suite 610 • Philadelphia, PA 19102-3684 Tel. 215-732-3774 • Fax 215-732-4401 FOREIGN POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE 2 Executive Summary This essay draws on Maurer’s talk at our history institute for teachers on America’s Entry into World War I, hosted and cosponsored by the First Division Museum at Cantigny in Wheaton, IL, April 9-10, 2016. -

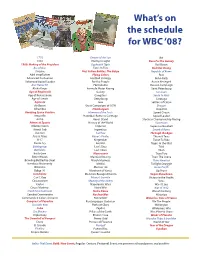

What's on the Schedule For

What’s on the schedule for WBC ‘08? 1776 Empire of the Sun Ra! 1830 Enemy In Sight Race For the Galaxy 1960: Making of the President Euphrat & Tigris Rail Baron Ace of Aces Facts In Five Red Star Rising Acquire Fast Action Battles: The Bulge Republic of Rome Adel Verpflichtet Flying Colors Risk Advanced Civilization Football Strategy Robo Rally Advanced Squad Leader For the People Russia Besieged ASL Starter Kit Formula De Russian Campaign Afrika Korps Formula Motor Racing Saint Petersburg Age of Empires III Galaxy San Juan Age of Renaissance Gangsters Santa Fe Rails Age of Steam Gettysburg Saratoga Agricola Goa Settlers of Catan Air Baron Great Campaigns of ACW Shogun Alhambra Hamburgum Slapshot Amazing Space Venture Hammer of the Scots Speed Circuit Amun-Re Hannibal: Rome vs Carthage Squad Leader Anzio Here I Stand Stockcar Championship Racing Athens & Sparta History of the World Successors Atlantic Storm Imperial Superstar Baseball Attack Sub Ingenious Sword of Rome Auction Ivanhoe Through the Ages Axis & Allies Kaiser's Pirates Thurn & Taxis B-17 Kingmaker Ticket To Ride Battle Cry Kremlin Tigers In the Mist Battlegroup Liar's Dice Tikal Battleline Lost Cities Titan BattleLore Manoeuver Titan Two Bitter Woods Manifest Destiny Titan: The Arena Brawling Battleship Steel March Madness Trans America Breakout Normandy Medici Twilight Struggle Britannia Memoir '44 Union Pacific Bulge '81 Merchant of Venus Up Front Candidate Monsters Ravage America Vegas Showdown Can't Stop Monty's Gamble Victory in the Pacific Carcassonne Mystery of the -

International Law and Naval Operations

JIJI International Law and Naval Operations James H. Doyle, Jr. N THE OVER TWO HUNDRED YEARS from American commerce raiding I in the Revolutionary War through two World Wars, the Korean and Vietnam wars, and a host of crises along the way, to the Persian Gulf conflict, peacekeeping, and peace enforcement, there has been a continuous evolution in the international law that governs naval operations. Equally changed has been the role of naval officers in applying oceans law and the rules of naval warfare in carrying out the mission of the command. This paper explores that evolution and the challenges that commanders and their operational lawyers will face in the 21st century. The Early Years and Global Wars Naval operations have been governed by international law since the early days of the Republic. Soon after the Continental Congress authorized fitting out armed vessels to disrupt British trade and reinforcement, the Colonies established Admiralty and Maritime courts to adjudicate prizes.1 American captains of warships and privateers were admonished to "respect the rights of neutrality" and "not to commit any such Violation of the Laws of Nations."z The first Navy Regulations enjoined a commanding officer to protect and defend his convoy in peace and war.3 In the War of 1812, frigate captains International Law and Naval Operations employed the traditional ruse de guerre in boarding merchant ships to suppress trade licensed by the enemy.4 President Lincoln's blockade of Confederate ports satisfied the criterion of effectiveness (ingress -

Few Americans in the 1790S Would Have Predicted That the Subject Of

AMERICAN NAVAL POLICY IN AN AGE OF ATLANTIC WARFARE: A CONSENSUS BROKEN AND REFORGED, 1783-1816 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jeffrey J. Seiken, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2007 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor John Guilmartin, Jr., Advisor Professor Margaret Newell _______________________ Professor Mark Grimsley Advisor History Graduate Program ABSTRACT In the 1780s, there was broad agreement among American revolutionaries like Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and Alexander Hamilton about the need for a strong national navy. This consensus, however, collapsed as a result of the partisan strife of the 1790s. The Federalist Party embraced the strategic rationale laid out by naval boosters in the previous decade, namely that only a powerful, seagoing battle fleet offered a viable means of defending the nation's vulnerable ports and harbors. Federalists also believed a navy was necessary to protect America's burgeoning trade with overseas markets. Republicans did not dispute the desirability of the Federalist goals, but they disagreed sharply with their political opponents about the wisdom of depending on a navy to achieve these ends. In place of a navy, the Republicans with Jefferson and Madison at the lead championed an altogether different prescription for national security and commercial growth: economic coercion. The Federalists won most of the legislative confrontations of the 1790s. But their very success contributed to the party's decisive defeat in the election of 1800 and the abandonment of their plans to create a strong blue water navy. -

Attitudes Towards Privateering During the Era of the Early American Republic

ATTITUDES TOWARDS PRIVATEERING DURING THE ERA OF THE EARLY AMERICAN REPUBLIC A Senior Honors Thesis by James R. Holcomb IV Submitted to the Office of Honors Programs & Academic Scholarships Texas A&M University In partial fulfillment of the requirements of the UNIVERSITY UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH FELLOWS April 2007 Major: History ii ABSTRACT Attitudes towards Privateering during the Era of the Early American Republic (April 2007) James R. Holcomb IV Department of History Texas A&M University Fellows Advisor: Dr. James C. Bradford Department of History Lacking sufficient funds to build and maintain a sizeable navy, the young United States was forced to employ privateers as a “stop-gap navy” in its struggles against stronger sea powers during the War for Independence, the Quasi War, and the War of 1812. Many American leaders opposed privateering on moral grounds, but felt compelled to employ it. Merchants and seamen were generally more supportive, wither because their usual employment, fishing and peaceful commerce, was denied them when enemies hovered outside American ports and began seizing American ships, or because privateering offered the prospect of quick and large profits. Sailors preferred service in iii privateers to enlisting in the navy because discipline tended to be less rigorous in privateers than in warships, privateers appeared safer since their captains generally tried to avoid combat with enemy men of war, and privateers offered the prospect of more prize money from the sale of captured ships. Officers in the Continental and United States Navy usually opposed privateering because privateers competed with them for recruits and for naval stores to fit their ships out for sea.