Mandible Cleft: Report of a Case and Review of the Literature*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is the Skeleton Male Or Female? the Pelvis Tells the Story

Activity: Is the Skeleton Male or Female? The pelvis tells the story. Distinct features adapted for childbearing distinguish adult females from males. Other bones and the skull also have features that can indicate sex, though less reliably. In young children, these sex-related features are less obvious and more difficult to interpret. Subtle sex differences are detectable in younger skeletons, but they become more defined following puberty and sexual maturation. What are the differences? Compare the two illustrations below in Figure 1. Female Pelvic Bones Male Pelvic Bones Broader sciatic notch Narrower sciatic notch Raised auricular surface Flat auricular surface Figure 1. Female and male pelvic bones. (Source: Smithsonian Institution, illustrated by Diana Marques) Figure 2. Pelvic bone of the skeleton in the cellar. (Source: Smithsonian Institution) Skull (Cranium and Mandible) Male Skulls Generally larger than female Larger projections behind the Larger brow ridges, with sloping, ears (mastoid processes) less rounded forehead Square chin with a more vertical Greater definition of muscle (acute) angle of the jaw attachment areas on the back of the head Figure 3. Male skulls. (Source: Smithsonian Institution, illustrated by Diana Marques) Female Skulls Smoother bone surfaces where Smaller projections behind the muscles attach ears (mastoid processes) Less pronounced brow ridges, Chin more pointed, with a larger, with more vertical forehead obtuse angle of the jaw Sharp upper margins of the eye orbits Figure 4. Female skulls. (Source: Smithsonian Institution, illustrated by Diana Marques) What Do You Think? Comparing the skull from the cellar in Figure 5 (below) with the illustrated male and female skulls in Figures 3 and 4, write Male or Female to note the sex depicted by each feature. -

The Cat Mandible (II): Manipulation of the Jaw, with a New Prosthesis Proposal, to Avoid Iatrogenic Complications

animals Review The Cat Mandible (II): Manipulation of the Jaw, with a New Prosthesis Proposal, to Avoid Iatrogenic Complications Matilde Lombardero 1,*,† , Mario López-Lombardero 2,†, Diana Alonso-Peñarando 3,4 and María del Mar Yllera 1 1 Unit of Veterinary Anatomy and Embryology, Department of Anatomy, Animal Production and Clinical Veterinary Sciences, Faculty of Veterinary Sciences, Campus of Lugo—University of Santiago de Compostela, 27002 Lugo, Spain; [email protected] 2 Engineering Polytechnic School of Gijón, University of Oviedo, 33203 Gijón, Spain; [email protected] 3 Department of Animal Pathology, Faculty of Veterinary Sciences, Campus of Lugo—University of Santiago de Compostela, 27002 Lugo, Spain; [email protected] 4 Veterinary Clinic Villaluenga, calle Centro n◦ 2, Villaluenga de la Sagra, 45520 Toledo, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-982-822-333 † Both authors contributed equally to this manuscript. Simple Summary: The small size of the feline mandible makes its manipulation difficult when fixing dislocations of the temporomandibular joint or mandibular fractures. In both cases, non-invasive techniques should be considered first. When not possible, fracture repair with internal fixation using bone plates would be the best option. Simple jaw fractures should be repaired first, and caudal to rostral. In addition, a ventral approach makes the bone fragments exposure and its manipulation easier. However, the cat mandible has little space to safely place the bone plate screws without damaging the tooth roots and/or the mandibular blood and nervous supply. As a consequence, we propose a conceptual model of a mandibular prosthesis that would provide biomechanical Citation: Lombardero, M.; stabilization, avoiding any unintended (iatrogenic) damage to those structures. -

Results Description of the SKULLS. the Overall Size of Both Skulls Was Considered to Be Within Normal Limits for Their Ethnic

Ossification Defects and Craniofacial Morphology In Incomplete Forms of Mandibulofacial Dysostosis A Description of Two Dry Skulls ERIK DAHL, D.D.S., DR. ODONT. ARNE BJORK, D.D.S., ODONT. DR. Copenhagen, Denmark The morphology of two East Indian dry skulls exhibiting anomalies which were suggested to represent incomplete forms of mandibulofacial dysostosis is described. Obvious although minor ossification anomalies were found localized to the temporal, sphenoid, the zygomatic, the maxillary and the mandibular bones. The observations substantiate the concept of the regional and bilateral nature of this malformation syndrome. Bilateral orbital deviations, hypoplasia of the malar bones, and incomplete zygomatic arches appear to be hard tissue aberrations which may be helpful in exami- nation for subclinical carrier status. Changes in mandibular morphology seem to be less distinguishing features in incomplete or abortive types of mandibulofacial dysostosis. KEY WORDS craniofacial problems, mandible, mandibulofacial dysostosis, maxilla, sphenoid bone, temporal bone, zygomatic bone Mandibulofacial dysostosis (MFD) often roentgencephalometric examinations were results in the development of a characteristic made of the skulls, and tomograms were ob- facial disfigurement with considerable simi- tained of the internal and middle ear. Com- larity between affected individuals. However, parisons were made with normal adult skulls the symptoms may vary highly in respect to and with an adult skull exhibiting the char- type and degree, and both incomplete and acteristics of MFD. All of the skulls were from abortive forms of the syndrome have been the same ethnic group. ' reported in the literature (Franceschetti and Klein, 1949; Moss et al., 1964; Rogers, 1964). Results In previous papers, we have shown the DEsCRIPTION OF THE SKULLS. -

GLOSSARY of MEDICAL and ANATOMICAL TERMS

GLOSSARY of MEDICAL and ANATOMICAL TERMS Abbreviations: • A. Arabic • abb. = abbreviation • c. circa = about • F. French • adj. adjective • G. Greek • Ge. German • cf. compare • L. Latin • dim. = diminutive • OF. Old French • ( ) plural form in brackets A-band abb. of anisotropic band G. anisos = unequal + tropos = turning; meaning having not equal properties in every direction; transverse bands in living skeletal muscle which rotate the plane of polarised light, cf. I-band. Abbé, Ernst. 1840-1905. German physicist; mathematical analysis of optics as a basis for constructing better microscopes; devised oil immersion lens; Abbé condenser. absorption L. absorbere = to suck up. acervulus L. = sand, gritty; brain sand (cf. psammoma body). acetylcholine an ester of choline found in many tissue, synapses & neuromuscular junctions, where it is a neural transmitter. acetylcholinesterase enzyme at motor end-plate responsible for rapid destruction of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter. acidophilic adj. L. acidus = sour + G. philein = to love; affinity for an acidic dye, such as eosin staining cytoplasmic proteins. acinus (-i) L. = a juicy berry, a grape; applied to small, rounded terminal secretory units of compound exocrine glands that have a small lumen (adj. acinar). acrosome G. akron = extremity + soma = body; head of spermatozoon. actin polymer protein filament found in the intracellular cytoskeleton, particularly in the thin (I-) bands of striated muscle. adenohypophysis G. ade = an acorn + hypophyses = an undergrowth; anterior lobe of hypophysis (cf. pituitary). adenoid G. " + -oeides = in form of; in the form of a gland, glandular; the pharyngeal tonsil. adipocyte L. adeps = fat (of an animal) + G. kytos = a container; cells responsible for storage and metabolism of lipids, found in white fat and brown fat. -

Paramedian Mandibular Cleft in a Patient Who Also Had Goldenhar 2

Brief Clinical Studies The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery & Volume 23, Number 1, January 2012 as the thyroid gland and hyoid bone, to determine whether any 10. Franzese C, Hayes JD, Nichols K. Congenital midline cervical cleft: a associated anomalies exist.3,16 Alternatively, CT or magnetic reso- report of two cases. Ear Nose Throat J 2008;87:166Y168 nance imaging may be performed for a more thorough assessment 11. Hirokawa S, Uotani H, Okami H, et al. A case of congenital midline of the soft tissue relationships; in our case, a CT scan of the neck cervical cleft with congenital heart disease. J Pediatr Surg Y confirmed a superficial subcutaneous cord, without deeper tissue 2003;38:1099 1101 involvement. To determine the source of airway obstruction, pre- 12. Tsukuno M, Kita Y, Kurihara K. A case of midline cervical cleft. Congenit Anom (Kyoto) 2002;42:143Y145 operative flexible laryngoscopy should be performed. 13. Vure S, Pang K, Hallam L, et al. Congenital midline cervical cleft Surgical treatment of CMCC is required to alleviate or prevent with an underlying bronchogenic like cyst. Pediatr Surg Int anterior neck contracture, respiratory distress, micrognathia, and 2009;25:811Y813 4,5,13 infection and for aesthetic reasons. Treatment involves the com- 14. Andryk JE, Kerschner JE, Hung RT, et al. Mid-line cervical cleft with a plete excision of the lesion and any involved tissues, followed by bronchogenic cyst. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 1999;47:261Y264 closure, which is most commonly performed with a Z-plasty or mul- 15. Agag R, Sacks J, Silver L. -

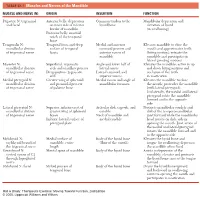

1 TABLE 23-1 Muscles and Nerves of the Mandible

0350 ch 23-Tab 10/12/04 12:19 PM Page 1 Chapter 23: The Temporomandibular Joint 1 TABLE 23-1 Muscles and Nerves of the Mandible MUSCLE AND NERVE (N) ORIGIN INSERTION FUNCTION Digastric N: trigeminal Anterior belly: depression Common tendon to the Mandibular depression and and facial on inner side of inferior hyoid bone elevation of hyoid border of mandible (in swallowing) Posterior belly: mastoid notch of the temporal bone Temporalis N: Temporal fossa and deep Medial and anterior Elevates mandible to close the mandibular division surface of temporal coronoid process and mouth and approximates teeth of trigeminal nerve fascia anterior ramus of (biting motion); retracts the mandible mandible and participates in lateral grinding motions Masseter N: Superficial: zygomatic Angle and lower half of Elevates the mandible; active in up mandibular division arch and maxillary process lateral ramus and down biting motions and of trigeminal nerve Deep portion: zygomatic Lateral coronoid and occlusion of the teeth arch superior ramus in mastication Medial pterygoid N: Greater wing of sphenoid Medial ramus and angle of Elevates the mandible to close mandibular division and pyramidal process mandibular foramen the mouth; protrudes the mandible of trigeminal nerve of palatine bone (with lateral pterygoid). Unilaterally, the medial and lateral pterygoid rotate the mandible forward and to the opposite side Lateral pterygoid N: Superior: inferior crest of Articular disk, capsule, and Protracts mandibular condyle and mandibular division greater wing of sphenoid condyle disk of the temporomandibular of trigeminal nerve bones Neck of mandible and joint forward while the mandibular Inferior: lateral surface of medial condyle head rotates on disk; aids in pterygoid plate opening the mouth. -

Illustrated Review of the Embryology and Development of the Facial

REVIEW ARTICLE Illustrated Review of the Embryology and Development of the Facial Region, Part 2: Late Development of the Fetal Face and Changes in the Face from the Newborn to Adulthood P.M. Som and T.P. Naidich ABSTRACT SUMMARY: The later embryogenesis of the fetal face and the alteration in the facial structure from birth to adulthood have been reviewed. Part 3 of the review will address the molecular mechanisms that are responsible for the changes described in parts 1 and 2. art 1 of this 3-part review primarily dealt with the early em- first make contact, each is completely covered by a homoge- Pbryologic development of the face and nasal cavity. Part 2 will neous epithelium. A special epithelium arises at the edge of discuss the later embryonic and fetal development of the face, and each palatal shelf, facilitating the eventual fusion of these changes in facial appearance from neonate to adulthood will be shelves. The epithelium on the nasal cavity surface of the palate reviewed. will differentiate into columnar ciliated epithelium. The epi- thelium on the oral cavity side of the palate will differentiate Formation of the Palate into stratified squamous epithelium. Between the sixth and 12th weeks, the palate is formed from 3 The 2 palatal shelves also fuse with the triangular primary pal- primordia: a midline median palatine process and paired lateral ate anteromedially to form a y-shaped fusion line. The point of palatine processes (Fig 1). In the beginning of the sixth week, fusion of the secondary palatal shelves with the primary palate is merging of the paired medial nasal processes forms the intermax- marked in the adult by the incisive foramen. -

A Review of the Mandibular and Maxillary Nerve Supplies and Their Clinical Relevance

AOB-2674; No. of Pages 12 a r c h i v e s o f o r a l b i o l o g y x x x ( 2 0 1 1 ) x x x – x x x Available online at www.sciencedirect.com journal homepage: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/aob Review A review of the mandibular and maxillary nerve supplies and their clinical relevance L.F. Rodella *, B. Buffoli, M. Labanca, R. Rezzani Division of Human Anatomy, Department of Biomedical Sciences and Biotechnologies, University of Brescia, V.le Europa 11, 25123 Brescia, Italy a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Mandibular and maxillary nerve supplies are described in most anatomy textbooks. Accepted 20 September 2011 Nevertheless, several anatomical variations can be found and some of them are clinically relevant. Keywords: Several studies have described the anatomical variations of the branching pattern of the trigeminal nerve in great detail. The aim of this review is to collect data from the literature Mandibular nerve and gives a detailed description of the innervation of the mandible and maxilla. Maxillary nerve We carried out a search of studies published in PubMed up to 2011, including clinical, Anatomical variations anatomical and radiological studies. This paper gives an overview of the main anatomical variations of the maxillary and mandibular nerve supplies, describing the anatomical variations that should be considered by the clinicians to understand pathological situations better and to avoid complications associated with anaesthesia and surgical procedures. # 2011 Elsevier Ltd. -

Embryology and Development: Mandible, Maxillary, Deciduous and Permanent Teeth

Central JSM Dentistry Review Article *Corresponding author Michel Goldberg, Department of Oral Biology, Faculty of Fundamental and Biomedical Sciences, Paris Embryology and Development: Cité University, France, Tel: 33 6 62 67 67 09 Email: [email protected] Submitted: 19 September 2019 Mandible, Maxillary, Deciduous and Accepted: 06 November 2019 Published: 08 November 2019 Permanent Teeth ISSN: 2333-7133 Copyright Michel Goldberg* © 2019 Goldberg M Department of Oral Biology, Paris Cité University, France OPEN ACCESS Abstract Keywords Endochondral and membranous (intramembranous) ossification control skeletogenesis. • Mandible In contrast to endochondral ossification, in which cartilage is replaced by bone, membranous • Maxillary mineralisation involves a highly vascular connective tissue, loaded by proliferating • Deciduous osteoprogenitor cells. The face is formed mostly by intramembranous bones (premaxillary, • Permanent maxillary, zygomatic, petrous portions of the temporal bone), with the contribution of the • Teeth frontal, parietal, the squamous portions of the temporal and interoccipital bones. Maxillary and mandible formation, tooth crown and root shaping are related to eruption. Dentin structure is also linked to teeth and bone early stages of development. Growth and transcription factors regulate tooth development, eruption, and resorption. Secretion of 4um/daily contribute to the von Ebner and/or Andresen lines, displaying dentin periodicity. INTRODUCTION The body of the mandible and the cartilaginous condyle replace Meckel’s cartilage. The condylar unit forms the articulation. Except the condylar process, the mandibular bone is The body of the mandible is the center of mandibular growth intramembranous and its development can be divided into a and the angula is formed in response to the lateral pterigoid pre-osteogenic phase, involving mesenchymal condensation, and and masseter muscles. -

Bone Diagram.Pub

Bone Diagram Forehead The common name of (Frontal bone) each bone is listed first, Nose bones with the scientific name (Nasals) given in parenthesis. Cheek bone (Zygoma) Upper jaw (Maxilla) Lower jaw (Mandible) Collar bone (Clavicle) Breast bone (Sternum) Upper arm bone (Humerus) Lower arm bone (Ulna) Lower arm bone (Radius) Thigh bone (Femur) Kneecap (Patella) Shin bone (Tibia) Calf bone (Fibula) Ankle bones (Tarsals) Foot bones (Metatarsals) Toe bones (Phalanges) Skull Side of skull (Cranium) (Parietal bone) Back of skull Did you know? (Occipital bone) When you are a baby you Temple have more than 300 (Temporal bone) bones. By the time you are an adult you only Backbone Neck vertebrae (7) have 206 bones, because (Spine) (Cervical vertebrae) some of your bones join together as you grow! Shoulder blade (Scapula) Chest vertebrae (12) (Thoracic vertebrae) Ribs (12 pairs) Lower back vertebrae (5) (Lumbar vertebrae) Fused vertebrae (5) (Sacrum) Pelvic bones (Ilium) (Pubis) (Ischium) Wrist bones (Carpals) Hand bones (Metacarpals) Finger bones Bones are important! (Phalanges) They hold up your body, and along with your muscles, keep you moving. Without your bones, you’d just be one big blob! To be able to grow, strong bones needs lots of calcium and weight-bearing physical activity. Heel bone (Calcaneus) University of Washington PKU Clinic CHDD - Box 357920, Seattle, WA 98195 (206) 685-3015, Toll Free in Washington State 877-685-3015 http://depts.washington.edu/pku . -

Glossary of Periodontal Terms.Pdf

THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF PERIODONTOLOGY Glossary of Periodontal Te rms 4th Edition Copyright 200 I by The American Academy of Periodontology Suite 800 737 North Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60611-2690 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, or otherwise without the express written permission of the publisher. ISBN 0-9264699-3-9 The first two editions of this publication were published under the title Glossary of Periodontic Terms as supplements to the Journal of Periodontology. First edition, January 1977 (Volume 48); second edition, November 1986 (Volume 57). The third edition was published under the title Glossary vf Periodontal Terms in 1992. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The fourth edition of the Glossary of Periodontal Terms represents four years of intensive work by many members of the Academy who generously contributed their time and knowledge to its development. This edition incorporates revised definitions of periodontal terms that were introduced at the 1996 World Workshop in Periodontics, as well as at the 1999 International Workshop for a Classification of Periodontal Diseases and Conditions. A review of the classification system from the 1999 Workshop has been included as an Appendix to the Glossary. Particular recognition is given to the members of the Subcommittee to Revise the Glossary of Periodontic Terms (Drs. Robert E. Cohen, Chair; Angelo Mariotti; Michael Rethman; and S. Jerome Zackin) who developed the revised material. Under the direction of Dr. Robert E. Cohen, the Committee on Research, Science and Therapy (Drs. David L. -

Osteonecrosis of the Jaw (ONJ)

Division of Oral Medicine and Dentistry Osteonecrosis of the Jaw (ONJ) What is ONJ? Osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) is a condition in which one Bisphosphonates may be taken either intravenously (IV) or or more parts of the jawbones become dead (necrotic) and orally as a pill. Te most commonly prescribed agents include exposed in the mouth. Tese fragments of bone poke through pamidronate (ArediaTM), alendronate (FosamaxTM), ibandronate the gums and may easily be mistaken for broken teeth. Both (BonivaTM), risedronate (ActonelTM), and zoledronic acid the upper (maxilla) and lower (mandible) jaw can be afected. (ZometaTM or ReclastTM). Alendronate is the most common Tis condition may develop for no obvious reason or may oral bisphosphonate and has a very low risk for causing ONJ. follow a dental extraction in which the socket fails to heal. Many IV bisphosphonates are administered much more frequently patients experience no symptoms at all, although symptoms for the cancer patient (once a month for the frst two years) may develop later. In some cases, the exposed bone is infected compared to osteoporosis patients (once a year only). Since it by oral bacteria, which may result in pain and swelling of the is the total amount of bisphosphonates received over time that surrounding gums. Sharp fragments of bone may cause painful is related to risk of ONJ, cancer patients face a much greater tongue sores. Large areas of necrotic bone are sometimes risk. Denosumab (ProliaTM, XgevaTM) is an IV medication that associated with loose or painful teeth that may require is approved for treatment of osteoporosis and cancer patients extraction.