Results Description of the SKULLS. the Overall Size of Both Skulls Was Considered to Be Within Normal Limits for Their Ethnic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is the Skeleton Male Or Female? the Pelvis Tells the Story

Activity: Is the Skeleton Male or Female? The pelvis tells the story. Distinct features adapted for childbearing distinguish adult females from males. Other bones and the skull also have features that can indicate sex, though less reliably. In young children, these sex-related features are less obvious and more difficult to interpret. Subtle sex differences are detectable in younger skeletons, but they become more defined following puberty and sexual maturation. What are the differences? Compare the two illustrations below in Figure 1. Female Pelvic Bones Male Pelvic Bones Broader sciatic notch Narrower sciatic notch Raised auricular surface Flat auricular surface Figure 1. Female and male pelvic bones. (Source: Smithsonian Institution, illustrated by Diana Marques) Figure 2. Pelvic bone of the skeleton in the cellar. (Source: Smithsonian Institution) Skull (Cranium and Mandible) Male Skulls Generally larger than female Larger projections behind the Larger brow ridges, with sloping, ears (mastoid processes) less rounded forehead Square chin with a more vertical Greater definition of muscle (acute) angle of the jaw attachment areas on the back of the head Figure 3. Male skulls. (Source: Smithsonian Institution, illustrated by Diana Marques) Female Skulls Smoother bone surfaces where Smaller projections behind the muscles attach ears (mastoid processes) Less pronounced brow ridges, Chin more pointed, with a larger, with more vertical forehead obtuse angle of the jaw Sharp upper margins of the eye orbits Figure 4. Female skulls. (Source: Smithsonian Institution, illustrated by Diana Marques) What Do You Think? Comparing the skull from the cellar in Figure 5 (below) with the illustrated male and female skulls in Figures 3 and 4, write Male or Female to note the sex depicted by each feature. -

The Cat Mandible (II): Manipulation of the Jaw, with a New Prosthesis Proposal, to Avoid Iatrogenic Complications

animals Review The Cat Mandible (II): Manipulation of the Jaw, with a New Prosthesis Proposal, to Avoid Iatrogenic Complications Matilde Lombardero 1,*,† , Mario López-Lombardero 2,†, Diana Alonso-Peñarando 3,4 and María del Mar Yllera 1 1 Unit of Veterinary Anatomy and Embryology, Department of Anatomy, Animal Production and Clinical Veterinary Sciences, Faculty of Veterinary Sciences, Campus of Lugo—University of Santiago de Compostela, 27002 Lugo, Spain; [email protected] 2 Engineering Polytechnic School of Gijón, University of Oviedo, 33203 Gijón, Spain; [email protected] 3 Department of Animal Pathology, Faculty of Veterinary Sciences, Campus of Lugo—University of Santiago de Compostela, 27002 Lugo, Spain; [email protected] 4 Veterinary Clinic Villaluenga, calle Centro n◦ 2, Villaluenga de la Sagra, 45520 Toledo, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-982-822-333 † Both authors contributed equally to this manuscript. Simple Summary: The small size of the feline mandible makes its manipulation difficult when fixing dislocations of the temporomandibular joint or mandibular fractures. In both cases, non-invasive techniques should be considered first. When not possible, fracture repair with internal fixation using bone plates would be the best option. Simple jaw fractures should be repaired first, and caudal to rostral. In addition, a ventral approach makes the bone fragments exposure and its manipulation easier. However, the cat mandible has little space to safely place the bone plate screws without damaging the tooth roots and/or the mandibular blood and nervous supply. As a consequence, we propose a conceptual model of a mandibular prosthesis that would provide biomechanical Citation: Lombardero, M.; stabilization, avoiding any unintended (iatrogenic) damage to those structures. -

Morfofunctional Structure of the Skull

N.L. Svintsytska V.H. Hryn Morfofunctional structure of the skull Study guide Poltava 2016 Ministry of Public Health of Ukraine Public Institution «Central Methodological Office for Higher Medical Education of MPH of Ukraine» Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukranian Medical Stomatological Academy» N.L. Svintsytska, V.H. Hryn Morfofunctional structure of the skull Study guide Poltava 2016 2 LBC 28.706 UDC 611.714/716 S 24 «Recommended by the Ministry of Health of Ukraine as textbook for English- speaking students of higher educational institutions of the MPH of Ukraine» (minutes of the meeting of the Commission for the organization of training and methodical literature for the persons enrolled in higher medical (pharmaceutical) educational establishments of postgraduate education MPH of Ukraine, from 02.06.2016 №2). Letter of the MPH of Ukraine of 11.07.2016 № 08.01-30/17321 Composed by: N.L. Svintsytska, Associate Professor at the Department of Human Anatomy of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukrainian Medical Stomatological Academy», PhD in Medicine, Associate Professor V.H. Hryn, Associate Professor at the Department of Human Anatomy of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukrainian Medical Stomatological Academy», PhD in Medicine, Associate Professor This textbook is intended for undergraduate, postgraduate students and continuing education of health care professionals in a variety of clinical disciplines (medicine, pediatrics, dentistry) as it includes the basic concepts of human anatomy of the skull in adults and newborns. Rewiewed by: O.M. Slobodian, Head of the Department of Anatomy, Topographic Anatomy and Operative Surgery of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Bukovinian State Medical University», Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor M.V. -

GLOSSARY of MEDICAL and ANATOMICAL TERMS

GLOSSARY of MEDICAL and ANATOMICAL TERMS Abbreviations: • A. Arabic • abb. = abbreviation • c. circa = about • F. French • adj. adjective • G. Greek • Ge. German • cf. compare • L. Latin • dim. = diminutive • OF. Old French • ( ) plural form in brackets A-band abb. of anisotropic band G. anisos = unequal + tropos = turning; meaning having not equal properties in every direction; transverse bands in living skeletal muscle which rotate the plane of polarised light, cf. I-band. Abbé, Ernst. 1840-1905. German physicist; mathematical analysis of optics as a basis for constructing better microscopes; devised oil immersion lens; Abbé condenser. absorption L. absorbere = to suck up. acervulus L. = sand, gritty; brain sand (cf. psammoma body). acetylcholine an ester of choline found in many tissue, synapses & neuromuscular junctions, where it is a neural transmitter. acetylcholinesterase enzyme at motor end-plate responsible for rapid destruction of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter. acidophilic adj. L. acidus = sour + G. philein = to love; affinity for an acidic dye, such as eosin staining cytoplasmic proteins. acinus (-i) L. = a juicy berry, a grape; applied to small, rounded terminal secretory units of compound exocrine glands that have a small lumen (adj. acinar). acrosome G. akron = extremity + soma = body; head of spermatozoon. actin polymer protein filament found in the intracellular cytoskeleton, particularly in the thin (I-) bands of striated muscle. adenohypophysis G. ade = an acorn + hypophyses = an undergrowth; anterior lobe of hypophysis (cf. pituitary). adenoid G. " + -oeides = in form of; in the form of a gland, glandular; the pharyngeal tonsil. adipocyte L. adeps = fat (of an animal) + G. kytos = a container; cells responsible for storage and metabolism of lipids, found in white fat and brown fat. -

98796-Anatomy of the Orbit

Anatomy of the orbit Prof. Pia C Sundgren MD, PhD Department of Diagnostic Radiology, Clinical Sciences, Lund University, Sweden Lund University / Faculty of Medicine / Inst. Clinical Sciences / Radiology / ECNR Dubrovnik / Oct 2018 Lund University / Faculty of Medicine / Inst. Clinical Sciences / Radiology / ECNR Dubrovnik / Oct 2018 Lay-out • brief overview of the basic anatomy of the orbit and its structures • the orbit is a complicated structure due to its embryological composition • high number of entities, and diseases due to its composition of ectoderm, surface ectoderm and mesoderm Recommend you to read for more details Lund University / Faculty of Medicine / Inst. Clinical Sciences / Radiology / ECNR Dubrovnik / Oct 2018 Lund University / Faculty of Medicine / Inst. Clinical Sciences / Radiology / ECNR Dubrovnik / Oct 2018 3 x 3 Imaging technique 3 layers: - neuroectoderm (retina, iris, optic nerve) - surface ectoderm (lens) • CT and / or MR - mesoderm (vascular structures, sclera, choroid) •IOM plane 3 spaces: - pre-septal •thin slices extraconal - post-septal • axial and coronal projections intraconal • CT: soft tissue and bone windows 3 motor nerves: - occulomotor (III) • MR: T1 pre and post, T2, STIR, fat suppression, DWI (?) - trochlear (IV) - abducens (VI) Lund University / Faculty of Medicine / Inst. Clinical Sciences / Radiology / ECNR Dubrovnik / Oct 2018 Lund University / Faculty of Medicine / Inst. Clinical Sciences / Radiology / ECNR Dubrovnik / Oct 2018 Superior orbital fissure • cranial nerves (CN) III, IV, and VI • lacrimal nerve • frontal nerve • nasociliary nerve • orbital branch of middle meningeal artery • recurrent branch of lacrimal artery • superior orbital vein • superior ophthalmic vein Lund University / Faculty of Medicine / Inst. Clinical Sciences / Radiology / ECNR Dubrovnik / Oct 2018 Lund University / Faculty of Medicine / Inst. -

Paramedian Mandibular Cleft in a Patient Who Also Had Goldenhar 2

Brief Clinical Studies The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery & Volume 23, Number 1, January 2012 as the thyroid gland and hyoid bone, to determine whether any 10. Franzese C, Hayes JD, Nichols K. Congenital midline cervical cleft: a associated anomalies exist.3,16 Alternatively, CT or magnetic reso- report of two cases. Ear Nose Throat J 2008;87:166Y168 nance imaging may be performed for a more thorough assessment 11. Hirokawa S, Uotani H, Okami H, et al. A case of congenital midline of the soft tissue relationships; in our case, a CT scan of the neck cervical cleft with congenital heart disease. J Pediatr Surg Y confirmed a superficial subcutaneous cord, without deeper tissue 2003;38:1099 1101 involvement. To determine the source of airway obstruction, pre- 12. Tsukuno M, Kita Y, Kurihara K. A case of midline cervical cleft. Congenit Anom (Kyoto) 2002;42:143Y145 operative flexible laryngoscopy should be performed. 13. Vure S, Pang K, Hallam L, et al. Congenital midline cervical cleft Surgical treatment of CMCC is required to alleviate or prevent with an underlying bronchogenic like cyst. Pediatr Surg Int anterior neck contracture, respiratory distress, micrognathia, and 2009;25:811Y813 4,5,13 infection and for aesthetic reasons. Treatment involves the com- 14. Andryk JE, Kerschner JE, Hung RT, et al. Mid-line cervical cleft with a plete excision of the lesion and any involved tissues, followed by bronchogenic cyst. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 1999;47:261Y264 closure, which is most commonly performed with a Z-plasty or mul- 15. Agag R, Sacks J, Silver L. -

Lab Manual Axial Skeleton Atla

1 PRE-LAB EXERCISES When studying the skeletal system, the bones are often sorted into two broad categories: the axial skeleton and the appendicular skeleton. This lab focuses on the axial skeleton, which consists of the bones that form the axis of the body. The axial skeleton includes bones in the skull, vertebrae, and thoracic cage, as well as the auditory ossicles and hyoid bone. In addition to learning about all the bones of the axial skeleton, it is also important to identify some significant bone markings. Bone markings can have many shapes, including holes, round or sharp projections, and shallow or deep valleys, among others. These markings on the bones serve many purposes, including forming attachments to other bones or muscles and allowing passage of a blood vessel or nerve. It is helpful to understand the meanings of some of the more common bone marking terms. Before we get started, look up the definitions of these common bone marking terms: Canal: Condyle: Facet: Fissure: Foramen: (see Module 10.18 Foramina of Skull) Fossa: Margin: Process: Throughout this exercise, you will notice bold terms. This is meant to focus your attention on these important words. Make sure you pay attention to any bold words and know how to explain their definitions and/or where they are located. Use the following modules to guide your exploration of the axial skeleton. As you explore these bones in Visible Body’s app, also locate the bones and bone markings on any available charts, models, or specimens. You may also find it helpful to palpate bones on yourself or make drawings of the bones with the bone markings labeled. -

MBB: Head & Neck Anatomy

MBB: Head & Neck Anatomy Skull Osteology • This is a comprehensive guide of all the skull features you must know by the practical exam. • Many of these structures will be presented multiple times during upcoming labs. • This PowerPoint Handout is the resource you will use during lab when you have access to skulls. Mind, Brain & Behavior 2021 Osteology of the Skull Slide Title Slide Number Slide Title Slide Number Ethmoid Slide 3 Paranasal Sinuses Slide 19 Vomer, Nasal Bone, and Inferior Turbinate (Concha) Slide4 Paranasal Sinus Imaging Slide 20 Lacrimal and Palatine Bones Slide 5 Paranasal Sinus Imaging (Sagittal Section) Slide 21 Zygomatic Bone Slide 6 Skull Sutures Slide 22 Frontal Bone Slide 7 Foramen RevieW Slide 23 Mandible Slide 8 Skull Subdivisions Slide 24 Maxilla Slide 9 Sphenoid Bone Slide 10 Skull Subdivisions: Viscerocranium Slide 25 Temporal Bone Slide 11 Skull Subdivisions: Neurocranium Slide 26 Temporal Bone (Continued) Slide 12 Cranial Base: Cranial Fossae Slide 27 Temporal Bone (Middle Ear Cavity and Facial Canal) Slide 13 Skull Development: Intramembranous vs Endochondral Slide 28 Occipital Bone Slide 14 Ossification Structures/Spaces Formed by More Than One Bone Slide 15 Intramembranous Ossification: Fontanelles Slide 29 Structures/Apertures Formed by More Than One Bone Slide 16 Intramembranous Ossification: Craniosynostosis Slide 30 Nasal Septum Slide 17 Endochondral Ossification Slide 31 Infratemporal Fossa & Pterygopalatine Fossa Slide 18 Achondroplasia and Skull Growth Slide 32 Ethmoid • Cribriform plate/foramina -

1 TABLE 23-1 Muscles and Nerves of the Mandible

0350 ch 23-Tab 10/12/04 12:19 PM Page 1 Chapter 23: The Temporomandibular Joint 1 TABLE 23-1 Muscles and Nerves of the Mandible MUSCLE AND NERVE (N) ORIGIN INSERTION FUNCTION Digastric N: trigeminal Anterior belly: depression Common tendon to the Mandibular depression and and facial on inner side of inferior hyoid bone elevation of hyoid border of mandible (in swallowing) Posterior belly: mastoid notch of the temporal bone Temporalis N: Temporal fossa and deep Medial and anterior Elevates mandible to close the mandibular division surface of temporal coronoid process and mouth and approximates teeth of trigeminal nerve fascia anterior ramus of (biting motion); retracts the mandible mandible and participates in lateral grinding motions Masseter N: Superficial: zygomatic Angle and lower half of Elevates the mandible; active in up mandibular division arch and maxillary process lateral ramus and down biting motions and of trigeminal nerve Deep portion: zygomatic Lateral coronoid and occlusion of the teeth arch superior ramus in mastication Medial pterygoid N: Greater wing of sphenoid Medial ramus and angle of Elevates the mandible to close mandibular division and pyramidal process mandibular foramen the mouth; protrudes the mandible of trigeminal nerve of palatine bone (with lateral pterygoid). Unilaterally, the medial and lateral pterygoid rotate the mandible forward and to the opposite side Lateral pterygoid N: Superior: inferior crest of Articular disk, capsule, and Protracts mandibular condyle and mandibular division greater wing of sphenoid condyle disk of the temporomandibular of trigeminal nerve bones Neck of mandible and joint forward while the mandibular Inferior: lateral surface of medial condyle head rotates on disk; aids in pterygoid plate opening the mouth. -

Topographical Anatomy and Morphometry of the Temporal Bone of the Macaque

Folia Morphol. Vol. 68, No. 1, pp. 13–22 Copyright © 2009 Via Medica O R I G I N A L A R T I C L E ISSN 0015–5659 www.fm.viamedica.pl Topographical anatomy and morphometry of the temporal bone of the macaque J. Wysocki 1Clinic of Otolaryngology and Rehabilitation, II Medical Faculty, Warsaw Medical University, Poland, Kajetany, Nadarzyn, Poland 2Laboratory of Clinical Anatomy of the Head and Neck, Institute of Physiology and Pathology of Hearing, Poland, Kajetany, Nadarzyn, Poland [Received 7 July 2008; Accepted 10 October 2008] Based on the dissections of 24 bones of 12 macaques (Macaca mulatta), a systematic anatomical description was made and measurements of the cho- sen size parameters of the temporal bone as well as the skull were taken. Although there is a small mastoid process, the general arrangement of the macaque’s temporal bone structures is very close to that which is observed in humans. The main differences are a different model of pneumatisation and the presence of subarcuate fossa, which possesses considerable dimensions. The main air space in the middle ear is the mesotympanum, but there are also additional air cells: the epitympanic recess containing the head of malleus and body of incus, the mastoid cavity, and several air spaces on the floor of the tympanic cavity. The vicinity of the carotid canal is also very well pneuma- tised and the walls of the canal are very thin. The semicircular canals are relatively small, very regular in shape, and characterized by almost the same dimensions. The bony walls of the labyrinth are relatively thin. -

The Axial Skeleton Visual Worksheet

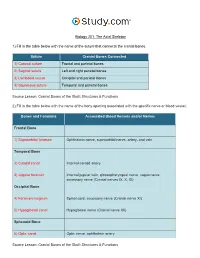

Biology 201: The Axial Skeleton 1) Fill in the table below with the name of the suture that connects the cranial bones. Suture Cranial Bones Connected 1) Coronal suture Frontal and parietal bones 2) Sagittal suture Left and right parietal bones 3) Lambdoid suture Occipital and parietal bones 4) Squamous suture Temporal and parietal bones Source Lesson: Cranial Bones of the Skull: Structures & Functions 2) Fill in the table below with the name of the bony opening associated with the specific nerve or blood vessel. Bones and Foramina Associated Blood Vessels and/or Nerves Frontal Bone 1) Supraorbital foramen Ophthalmic nerve, supraorbital nerve, artery, and vein Temporal Bone 2) Carotid canal Internal carotid artery 3) Jugular foramen Internal jugular vein, glossopharyngeal nerve, vagus nerve, accessory nerve (Cranial nerves IX, X, XI) Occipital Bone 4) Foramen magnum Spinal cord, accessory nerve (Cranial nerve XI) 5) Hypoglossal canal Hypoglossal nerve (Cranial nerve XII) Sphenoid Bone 6) Optic canal Optic nerve, ophthalmic artery Source Lesson: Cranial Bones of the Skull: Structures & Functions 3) Label the anterior view of the skull below with its correct feature. Frontal bone Palatine bone Ethmoid bone Nasal septum: Perpendicular plate of ethmoid bone Sphenoid bone Inferior orbital fissure Inferior nasal concha Maxilla Orbit Vomer bone Supraorbital margin Alveolar process of maxilla Middle nasal concha Inferior nasal concha Coronal suture Mandible Glabella Mental foramen Nasal bone Parietal bone Supraorbital foramen Orbital canal Temporal bone Lacrimal bone Orbit Alveolar process of mandible Superior orbital fissure Zygomatic bone Infraorbital foramen Source Lesson: Facial Bones of the Skull: Structures & Functions 4) Label the right lateral view of the skull below with its correct feature. -

Illustrated Review of the Embryology and Development of the Facial

REVIEW ARTICLE Illustrated Review of the Embryology and Development of the Facial Region, Part 2: Late Development of the Fetal Face and Changes in the Face from the Newborn to Adulthood P.M. Som and T.P. Naidich ABSTRACT SUMMARY: The later embryogenesis of the fetal face and the alteration in the facial structure from birth to adulthood have been reviewed. Part 3 of the review will address the molecular mechanisms that are responsible for the changes described in parts 1 and 2. art 1 of this 3-part review primarily dealt with the early em- first make contact, each is completely covered by a homoge- Pbryologic development of the face and nasal cavity. Part 2 will neous epithelium. A special epithelium arises at the edge of discuss the later embryonic and fetal development of the face, and each palatal shelf, facilitating the eventual fusion of these changes in facial appearance from neonate to adulthood will be shelves. The epithelium on the nasal cavity surface of the palate reviewed. will differentiate into columnar ciliated epithelium. The epi- thelium on the oral cavity side of the palate will differentiate Formation of the Palate into stratified squamous epithelium. Between the sixth and 12th weeks, the palate is formed from 3 The 2 palatal shelves also fuse with the triangular primary pal- primordia: a midline median palatine process and paired lateral ate anteromedially to form a y-shaped fusion line. The point of palatine processes (Fig 1). In the beginning of the sixth week, fusion of the secondary palatal shelves with the primary palate is merging of the paired medial nasal processes forms the intermax- marked in the adult by the incisive foramen.