The Cat Mandible (II): Manipulation of the Jaw, with a New Prosthesis Proposal, to Avoid Iatrogenic Complications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary for Narrative Writing

Periodontal Assessment and Treatment Planning Gingival description Color: o pink o erythematous o cyanotic o racial pigmentation o metallic pigmentation o uniformity Contour: o recession o clefts o enlarged papillae o cratered papillae o blunted papillae o highly rolled o bulbous o knife-edged o scalloped o stippled Consistency: o firm o edematous o hyperplastic o fibrotic Band of gingiva: o amount o quality o location o treatability Bleeding tendency: o sulcus base, lining o gingival margins Suppuration Sinus tract formation Pocket depths Pseudopockets Frena Pain Other pathology Dental Description Defective restorations: o overhangs o open contacts o poor contours Fractured cusps 1 ww.links2success.biz [email protected] 914-303-6464 Caries Deposits: o Type . plaque . calculus . stain . matera alba o Location . supragingival . subgingival o Severity . mild . moderate . severe Wear facets Percussion sensitivity Tooth vitality Attrition, erosion, abrasion Occlusal plane level Occlusion findings Furcations Mobility Fremitus Radiographic findings Film dates Crown:root ratio Amount of bone loss o horizontal; vertical o localized; generalized Root length and shape Overhangs Bulbous crowns Fenestrations Dehiscences Tooth resorption Retained root tips Impacted teeth Root proximities Tilted teeth Radiolucencies/opacities Etiologic factors Local: o plaque o calculus o overhangs 2 ww.links2success.biz [email protected] 914-303-6464 o orthodontic apparatus o open margins o open contacts o improper -

Establishment of a Dental Effects of Hypophosphatasia Registry Thesis

Establishment of a Dental Effects of Hypophosphatasia Registry Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jennifer Laura Winslow, DMD Graduate Program in Dentistry The Ohio State University 2018 Thesis Committee Ann Griffen, DDS, MS, Advisor Sasigarn Bowden, MD Brian Foster, PhD Copyrighted by Jennifer Laura Winslow, D.M.D. 2018 Abstract Purpose: Hypophosphatasia (HPP) is a metabolic disease that affects development of mineralized tissues including the dentition. Early loss of primary teeth is a nearly universal finding, and although problems in the permanent dentition have been reported, findings have not been described in detail. In addition, enzyme replacement therapy is now available, but very little is known about its effects on the dentition. HPP is rare and few dental providers see many cases, so a registry is needed to collect an adequate sample to represent the range of manifestations and the dental effects of enzyme replacement therapy. Devising a way to recruit patients nationally while still meeting the IRB requirements for human subjects research presented multiple challenges. Methods: A way to recruit patients nationally while still meeting the local IRB requirements for human subjects research was devised in collaboration with our Office of Human Research. The solution included pathways for obtaining consent and transferring protected information, and required that the clinician providing the clinical data refer the patient to the study and interact with study personnel only after the patient has given permission. Data forms and a custom database application were developed. Results: The registry is established and has been successfully piloted with 2 participants, and we are now initiating wider recruitment. -

Is the Skeleton Male Or Female? the Pelvis Tells the Story

Activity: Is the Skeleton Male or Female? The pelvis tells the story. Distinct features adapted for childbearing distinguish adult females from males. Other bones and the skull also have features that can indicate sex, though less reliably. In young children, these sex-related features are less obvious and more difficult to interpret. Subtle sex differences are detectable in younger skeletons, but they become more defined following puberty and sexual maturation. What are the differences? Compare the two illustrations below in Figure 1. Female Pelvic Bones Male Pelvic Bones Broader sciatic notch Narrower sciatic notch Raised auricular surface Flat auricular surface Figure 1. Female and male pelvic bones. (Source: Smithsonian Institution, illustrated by Diana Marques) Figure 2. Pelvic bone of the skeleton in the cellar. (Source: Smithsonian Institution) Skull (Cranium and Mandible) Male Skulls Generally larger than female Larger projections behind the Larger brow ridges, with sloping, ears (mastoid processes) less rounded forehead Square chin with a more vertical Greater definition of muscle (acute) angle of the jaw attachment areas on the back of the head Figure 3. Male skulls. (Source: Smithsonian Institution, illustrated by Diana Marques) Female Skulls Smoother bone surfaces where Smaller projections behind the muscles attach ears (mastoid processes) Less pronounced brow ridges, Chin more pointed, with a larger, with more vertical forehead obtuse angle of the jaw Sharp upper margins of the eye orbits Figure 4. Female skulls. (Source: Smithsonian Institution, illustrated by Diana Marques) What Do You Think? Comparing the skull from the cellar in Figure 5 (below) with the illustrated male and female skulls in Figures 3 and 4, write Male or Female to note the sex depicted by each feature. -

Feline Tooth Resorption Feline Odontoclastic Resorptive Lesions (FORL)

Feline Tooth Resorption Feline Odontoclastic Resorptive Lesions (FORL) What is tooth resorption? Tooth resorption is a destructive process that eats away at teeth and is quite common in cats. Up to 50% of cats over the age of 8 will have resorptive lesions. Of those 50% with lesions, 50% of them will have more than one. This process can be very painful, and due to the nature of the cat, many will not show obvious signs of pain. These lesions will often require immediate treatment. Feline tooth resorption does progress and will require treatment to avoid pain and loss of function. This process is not necessarily preventable, but studies do show that cats who do not receive oral hygiene care are at an increased risk of development of resorptive lesions. Feline patients diagnosed with Feline Immunodeficiency Virus and Feline Leukemia Virus are also more likely to develop lesions. Despite the health status of your cat, it is important to know tooth resorption is a common and treatable disease. What causes tooth resorption? Tooth resorption is an idiopathic disease of the teeth. This means that the cause is unknown. We do know odontoclasts, the cat’s own cells, begin to destroy the structure of the tooth. Sometimes resorption will be associated with a tooth root abscess, although this is uncommon. What are the clinical signs of this? Cats with tooth resorption will often have inflammation of the gum tissue surrounding the affected tooth. Your veterinarian will comment on the teeth and gums during the oral part of the physical examination. Even though an oral exam is done, many of these lesions are below the gum line and require dental radiography to fully diagnose. -

Feline Alveolar Osteitis Treatment Planning: Implant Protocol with Osseodensification and Early Crown Placement Rocco E

Feline Alveolar Osteitis Treatment Planning: Implant Protocol with Osseodensification and Early Crown Placement Rocco E. Mele DVM1, Gregori M. Kurtzman, DDS, MAGD, DICOI,DIDIA2 1 Eastpoint Pet Clinic, Tucson, A, USA 2 Silver Spring, MD, USA Abstract: Feline dental implants are becoming a predictable and viable treatment option for the replacement of lost canines due to maxillary Alveolar Osteitis (AO) a painful condition, commonly experienced by a growing number of cats. Surgical extraction and debridement remains the treatment of choice for this complex inflammatory process. However, future complications can be a common sequela of maxillary canine loss. This case will demonstrate the successful surgical extraction of a maxillary canine with implant placement following the osseodensification protocol and utilizing the sockets osteitis buttressing bone formation to promote a positive result with final crown restoration 13 weeks following implant placement. Introduction: Alveolar Osteitis (AO) is a chronic inflammatory process more often diagnosed in maxillary canine sockets of the feline patient. Clinical presentation may include oral pain, bleeding, periodontitis, tooth resorption (ORL), and alveolar buccal bone changes.1-5 Clinical Features: A presumptive diagnosis of (AO) is made on the awake patient, documenting clinical features such as; gingivitis with soft tissue swelling, gingival mucosal erythema, buccal bone expansion, and coronal extrusion. (Figure 1) Radiographic Features: Radiographic changes are identified under general anesthesia. These bony changes and pathology may include; deep palatal probing (Figure 2 red), alveolar bone expansion (Figure 2 green), buttressing condensing bone (Figure 2 blue) and a mottled osseous appearance mimicking rough, large trabeculae (Figure 2 yellow) Osseodensification (OD): OD is a novel biomechanical bone preparation technique for dental implant placement to improve bone quality by increasing its density utilizing Densah burs. -

Analyses of Thoracic and Lumbar Spine Injuries in Frontal Impacts

IRC-13-17 Analyses of Thoracic and Lumbar Spine Injuries in Frontal IRCOBIImpacts Conference 2013 Thorsten Adolph, Marcus Wisch, Andre Eggers, Heiko Johannsen, Richard Cuerden, Jolyon Carroll, David Hynd, Ulrich Sander Abstract In general the passive safety capability is much greater in newer versus older cars due to the stiff compartment preventing intrusion in severe collisions. However, the stiffer structure which increases the deceleration can lead to a change in injury patterns. In order to analyse possible injury mechanisms for thoracic and lumbar spine injuries, data from the German In‐Depth Accident Study (GIDAS) were used in this study. A two‐step approach of statistical and case‐by‐case analysis was applied for this investigation. In total 4,289 collisions were selected involving 8,844 vehicles, 5,765 injured persons and 9,468 coded injuries. Thoracic and lumbar spine injuries such as burst, compression or dislocation fractures as well as soft tissue injuries were found to occur in frontal impacts even without intrusion to the passenger compartment. If a MAIS 2+ injury occurred, in 15% of the cases a thoracic and/or lumbar spine injury is included. Considering AIS 2+ thoracic and lumbar spine, most injuries were fractures and occurred in the lumbar spine area. From the case by case analyses it can be concluded that lumbar spine fractures occur in accidents without the engagement of longitudinals, lateral loading to the occupant and/or very severe accidents with MAIS being much higher than the spine AIS. Keywords accident analysis, injuries, frontal impact, lumbar spine, thoracic spine I. INTRODUCTION With the introduction of lap belts a new injury pattern, the so called seat belt syndrome, was observed [1]. -

An Insight Into Internal Resorption

Hindawi Publishing Corporation ISRN Dentistry Volume 2014, Article ID 759326, 7 pages http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/759326 Review Article An Insight into Internal Resorption Priya Thomas, Rekha Krishna Pillai, Bindhu Pushparajan Ramakrishnan, and Jayanthi Palani Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, Annoor Dental College & Hospital, Muvattupuzha, Ernakulam District, Kerala 686673, India Correspondence should be addressed to Priya Thomas; [email protected] Received 20 January 2014; Accepted 27 March 2014; Published 12 May 2014 Academic Editors: S.-C. Choi and G. Mount Copyright © 2014 Priya Thomas et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Internal resorption, a rare phenomenon, has been a quandary from the standpoints of both its diagnosis and treatment. It is usually asymptomatic and discovered by chance on routine radiographic examinations or by a classic clinical sign, “pink spot” in the crown. This paper emphasizes the etiology and pathophysiologic mechanisms involved in internal root resorption. Prognosis is good for smaller lesions; however, for those with extensive resorption associated with perforation the tooth structure is greatly weakened and the prognosis remains poor. 1. Introduction teeth. Unlike the deciduous teeth, the permanent teeth rarely undergo resorption unless stimulated by a pathological Tooth resorption presents itself either as a physiological process. Pathologic resorption occurs following traumatic or a pathological process occurring internally (pulpally injuries, orthodontic tooth movement, or chronic infections derived) or externally (periodontally derived). According to of the pulp or periodontal structures [1]. -

Results Description of the SKULLS. the Overall Size of Both Skulls Was Considered to Be Within Normal Limits for Their Ethnic

Ossification Defects and Craniofacial Morphology In Incomplete Forms of Mandibulofacial Dysostosis A Description of Two Dry Skulls ERIK DAHL, D.D.S., DR. ODONT. ARNE BJORK, D.D.S., ODONT. DR. Copenhagen, Denmark The morphology of two East Indian dry skulls exhibiting anomalies which were suggested to represent incomplete forms of mandibulofacial dysostosis is described. Obvious although minor ossification anomalies were found localized to the temporal, sphenoid, the zygomatic, the maxillary and the mandibular bones. The observations substantiate the concept of the regional and bilateral nature of this malformation syndrome. Bilateral orbital deviations, hypoplasia of the malar bones, and incomplete zygomatic arches appear to be hard tissue aberrations which may be helpful in exami- nation for subclinical carrier status. Changes in mandibular morphology seem to be less distinguishing features in incomplete or abortive types of mandibulofacial dysostosis. KEY WORDS craniofacial problems, mandible, mandibulofacial dysostosis, maxilla, sphenoid bone, temporal bone, zygomatic bone Mandibulofacial dysostosis (MFD) often roentgencephalometric examinations were results in the development of a characteristic made of the skulls, and tomograms were ob- facial disfigurement with considerable simi- tained of the internal and middle ear. Com- larity between affected individuals. However, parisons were made with normal adult skulls the symptoms may vary highly in respect to and with an adult skull exhibiting the char- type and degree, and both incomplete and acteristics of MFD. All of the skulls were from abortive forms of the syndrome have been the same ethnic group. ' reported in the literature (Franceschetti and Klein, 1949; Moss et al., 1964; Rogers, 1964). Results In previous papers, we have shown the DEsCRIPTION OF THE SKULLS. -

GLOSSARY of MEDICAL and ANATOMICAL TERMS

GLOSSARY of MEDICAL and ANATOMICAL TERMS Abbreviations: • A. Arabic • abb. = abbreviation • c. circa = about • F. French • adj. adjective • G. Greek • Ge. German • cf. compare • L. Latin • dim. = diminutive • OF. Old French • ( ) plural form in brackets A-band abb. of anisotropic band G. anisos = unequal + tropos = turning; meaning having not equal properties in every direction; transverse bands in living skeletal muscle which rotate the plane of polarised light, cf. I-band. Abbé, Ernst. 1840-1905. German physicist; mathematical analysis of optics as a basis for constructing better microscopes; devised oil immersion lens; Abbé condenser. absorption L. absorbere = to suck up. acervulus L. = sand, gritty; brain sand (cf. psammoma body). acetylcholine an ester of choline found in many tissue, synapses & neuromuscular junctions, where it is a neural transmitter. acetylcholinesterase enzyme at motor end-plate responsible for rapid destruction of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter. acidophilic adj. L. acidus = sour + G. philein = to love; affinity for an acidic dye, such as eosin staining cytoplasmic proteins. acinus (-i) L. = a juicy berry, a grape; applied to small, rounded terminal secretory units of compound exocrine glands that have a small lumen (adj. acinar). acrosome G. akron = extremity + soma = body; head of spermatozoon. actin polymer protein filament found in the intracellular cytoskeleton, particularly in the thin (I-) bands of striated muscle. adenohypophysis G. ade = an acorn + hypophyses = an undergrowth; anterior lobe of hypophysis (cf. pituitary). adenoid G. " + -oeides = in form of; in the form of a gland, glandular; the pharyngeal tonsil. adipocyte L. adeps = fat (of an animal) + G. kytos = a container; cells responsible for storage and metabolism of lipids, found in white fat and brown fat. -

Paramedian Mandibular Cleft in a Patient Who Also Had Goldenhar 2

Brief Clinical Studies The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery & Volume 23, Number 1, January 2012 as the thyroid gland and hyoid bone, to determine whether any 10. Franzese C, Hayes JD, Nichols K. Congenital midline cervical cleft: a associated anomalies exist.3,16 Alternatively, CT or magnetic reso- report of two cases. Ear Nose Throat J 2008;87:166Y168 nance imaging may be performed for a more thorough assessment 11. Hirokawa S, Uotani H, Okami H, et al. A case of congenital midline of the soft tissue relationships; in our case, a CT scan of the neck cervical cleft with congenital heart disease. J Pediatr Surg Y confirmed a superficial subcutaneous cord, without deeper tissue 2003;38:1099 1101 involvement. To determine the source of airway obstruction, pre- 12. Tsukuno M, Kita Y, Kurihara K. A case of midline cervical cleft. Congenit Anom (Kyoto) 2002;42:143Y145 operative flexible laryngoscopy should be performed. 13. Vure S, Pang K, Hallam L, et al. Congenital midline cervical cleft Surgical treatment of CMCC is required to alleviate or prevent with an underlying bronchogenic like cyst. Pediatr Surg Int anterior neck contracture, respiratory distress, micrognathia, and 2009;25:811Y813 4,5,13 infection and for aesthetic reasons. Treatment involves the com- 14. Andryk JE, Kerschner JE, Hung RT, et al. Mid-line cervical cleft with a plete excision of the lesion and any involved tissues, followed by bronchogenic cyst. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 1999;47:261Y264 closure, which is most commonly performed with a Z-plasty or mul- 15. Agag R, Sacks J, Silver L. -

Why Fuse the Mandibular Symphysis? a Comparative Analysis

AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PHYSICAL ANTHROPOLOGY 112:517–540 (2000) Why Fuse the Mandibular Symphysis? A Comparative Analysis D.E. LIEBERMAN1,2 AND A.W. CROMPTON2 1Department of Anthropology, George Washington University, Washington, DC 20052, and Human Origins Program, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC 20560 2Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 KEY WORDS symphysis; mammals; primates; electromyograms; mandible; mastication ABSTRACT Fused symphyses, which evolved independently in several mammalian taxa, including anthropoids, are stiffer and stronger than un- fused symphyses. This paper tests the hypothesis that orientations of tooth movements during occlusion are the primary basis for variations in symph- yseal fusion. Mammals whose teeth have primarily dorsally oriented occlusal trajectories and/or rotate their mandibles during occlusion will not benefit from symphyseal fusion because it prevents independent mandibular move- ments and because unfused symphyses transfer dorsally oriented forces with equal efficiency; mammals with predominantly transverse power strokes are predicted to benefit from symphyseal fusion or greatly restricted mediolateral movement at the symphysis in order to increase force transfer efficiency across the symphysis in the transverse plane. These hypotheses are tested with comparative data on symphyseal and occlusal morphology in several mammals, and with kinematic and EMG analyses of mastication in opossums (Didelphis virginiana) and -

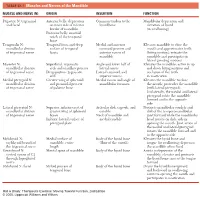

1 TABLE 23-1 Muscles and Nerves of the Mandible

0350 ch 23-Tab 10/12/04 12:19 PM Page 1 Chapter 23: The Temporomandibular Joint 1 TABLE 23-1 Muscles and Nerves of the Mandible MUSCLE AND NERVE (N) ORIGIN INSERTION FUNCTION Digastric N: trigeminal Anterior belly: depression Common tendon to the Mandibular depression and and facial on inner side of inferior hyoid bone elevation of hyoid border of mandible (in swallowing) Posterior belly: mastoid notch of the temporal bone Temporalis N: Temporal fossa and deep Medial and anterior Elevates mandible to close the mandibular division surface of temporal coronoid process and mouth and approximates teeth of trigeminal nerve fascia anterior ramus of (biting motion); retracts the mandible mandible and participates in lateral grinding motions Masseter N: Superficial: zygomatic Angle and lower half of Elevates the mandible; active in up mandibular division arch and maxillary process lateral ramus and down biting motions and of trigeminal nerve Deep portion: zygomatic Lateral coronoid and occlusion of the teeth arch superior ramus in mastication Medial pterygoid N: Greater wing of sphenoid Medial ramus and angle of Elevates the mandible to close mandibular division and pyramidal process mandibular foramen the mouth; protrudes the mandible of trigeminal nerve of palatine bone (with lateral pterygoid). Unilaterally, the medial and lateral pterygoid rotate the mandible forward and to the opposite side Lateral pterygoid N: Superior: inferior crest of Articular disk, capsule, and Protracts mandibular condyle and mandibular division greater wing of sphenoid condyle disk of the temporomandibular of trigeminal nerve bones Neck of mandible and joint forward while the mandibular Inferior: lateral surface of medial condyle head rotates on disk; aids in pterygoid plate opening the mouth.