Recent Language Change in Shoshone: Structural Consequences of Language Loss

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Is Kanakanavu an Ergative Language?

Voice and transitivity in Kanakanavu Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades einer Doktorin der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) der Philosophischen Fakultät der Universität Erfurt vorgelegt von Ilka Wild Erfurt, März 2018 Gutachter der Arbeit: Prof. Dr. Christian Lehmann, Universität Erfurt Prof. Dr. Volker Gast, Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena Datum der Defensio: 6. August 2018 Universitätsbibliothek Erfurt Electronic Text Center URN:nbn:de:gbv:547-201800530 Abstract This is a dissertation on the Kanakanavu language, i.e. that linguistic phenomena found while working on the language underwent a deeper analysis and linguistic techniques were used to provide data and to present analyses in a structured manner. Various topics of the Kanakanavu language system are exemplified: Starting with a grammar sketch of the language, the domains phonology, morphology, and syntax are described and information on the linguistic features in these domains are given. Beyond a general overview of the situation and a brief description of the language and its speakers, an investigation on a central part of the Kanakanavu language system, namely its voice system, can be found in this work. First, it is analyzed and described by its formal characteristics. Second, the question of the motivation of using the voice system in connection to transitivity and, in the literature less often recognized, the semantic side of transitive constructions, i.e. its effectiveness, is discussed. Investigations on verb classes in Kanakanavu and possible semantic connections are presented as well as investigations on possible situations of different degrees of effectiveness. This enables a more detailed view on the language system and, in particular, its voice system. -

A View from Amazonia

1 The value of language and the language of value: a view from Amazonia Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald (The Cairns Institute/SASS, JCU) Abstract. The concept of 'value' is manifold. Something judged good, proper and desirable in human life is judged as 'valuable'. Being valuable may have economic connotations of 'worth' — to do with the degree to which desirable objects may bring material benefits. In this paper, I concentrate on the Tariana, a representative of the Vaupés River Basin linguistic area in the far-corner of north-west Brazilian Amazonia. I focus on how the value of language as the mark of identity is expressed in Tariana. I then turn to the expression of meanings to do with evaluation ('good, proper, as it should be' versus 'bad, adverse', 'other', or 'correct' versus 'incorrect'(), with a special focus on the danger of 'otherness'. The concept of monetary worth came into the society, and the language, through the introduction of market economy within the last two or three decades. At the end, the findings are put within the perspective of Amazonian languages and cultures in general. 1 Value in language The concept of 'value' is manifold. Something judged good, proper and desirable in human life may be looked upon as 'valuable'. Having 'value' may go together with economic connotations of 'worth', that is, the degree to which desirable objects may bring material benefits. The term 'value' in English (and also French, Portuguese and some other familiar Indo-European languages) extends beyond 'worth' and 'evaluation' into 'the ability of a thing to serve a purpose or cause an effect, as in news value'. -

Baby Girl Names Registered in 2018

Page 1 of 46 Baby Girl Names Registered in 2018 Frequency Name Frequency Name Frequency Name 8 Aadhya 1 Aayza 1 Adalaide 1 Aadi 1 Abaani 2 Adalee 1 Aaeesha 1 Abagale 1 Adaleia 1 Aafiyah 1 Abaigeal 1 Adaleigh 4 Aahana 1 Abayoo 1 Adalia 1 Aahna 2 Abbey 13 Adaline 1 Aaila 4 Abbie 1 Adallynn 3 Aaima 1 Abbigail 22 Adalyn 3 Aaira 17 Abby 1 Adalynd 1 Aaiza 1 Abbyanna 1 Adalyne 1 Aaliah 1 Abegail 19 Adalynn 1 Aalina 1 Abelaket 1 Adalynne 33 Aaliyah 2 Abella 1 Adan 1 Aaliyah-Jade 2 Abi 1 Adan-Rehman 1 Aalizah 1 Abiageal 1 Adara 1 Aalyiah 1 Abiela 3 Addalyn 1 Aamber 153 Abigail 2 Addalynn 1 Aamilah 1 Abigaille 1 Addalynne 1 Aamina 1 Abigail-Yonas 1 Addeline 1 Aaminah 3 Abigale 2 Addelynn 1 Aanvi 1 Abigayle 3 Addilyn 2 Aanya 1 Abiha 1 Addilynn 1 Aara 1 Abilene 66 Addison 1 Aaradhya 1 Abisha 3 Addisyn 1 Aaral 1 Abisola 1 Addy 1 Aaralyn 1 Abla 9 Addyson 1 Aaralynn 1 Abraj 1 Addyzen-Jerynne 1 Aarao 1 Abree 1 Adea 2 Aaravi 1 Abrianna 1 Adedoyin 1 Aarcy 4 Abrielle 1 Adela 2 Aaria 1 Abrienne 25 Adelaide 2 Aariah 1 Abril 1 Adelaya 1 Aarinya 1 Abrish 5 Adele 1 Aarmi 2 Absalat 1 Adeleine 2 Aarna 1 Abuk 1 Adelena 1 Aarnavi 1 Abyan 2 Adelin 1 Aaro 1 Acacia 5 Adelina 1 Aarohi 1 Acadia 35 Adeline 1 Aarshi 1 Acelee 1 Adéline 2 Aarushi 1 Acelyn 1 Adelita 1 Aarvi 2 Acelynn 1 Adeljine 8 Aarya 1 Aceshana 1 Adelle 2 Aaryahi 1 Achai 21 Adelyn 1 Aashvi 1 Achan 2 Adelyne 1 Aasiyah 1 Achankeng 12 Adelynn 1 Aavani 1 Achel 1 Aderinsola 1 Aaverie 1 Achok 1 Adetoni 4 Aavya 1 Achol 1 Adeyomola 1 Aayana 16 Ada 1 Adhel 2 Aayat 1 Adah 1 Adhvaytha 1 Aayath 1 Adahlia 1 Adilee 1 -

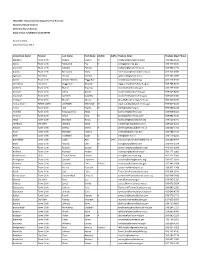

Massdor - Massachusetts Department of Revenue Division of Local Services Directory Search Results Report Date: 2/10/2021 10:32:24 PM

MassDOR - Massachusetts Department of Revenue Division of Local Services Directory Search Results Report Date: 2/10/2021 10:32:24 PM Search Criteria : City Clerk/Town Clerk Jurisdiction Name Position Last Name First Name Middle Suffix Position Email Position Main Phone Abington Town Clerk Adams Leanne M.Name [email protected] 781-982-2112 Acton Town Clerk Szkaradek Eva K. [email protected] 978-929-6620 Acushnet Town Clerk Labonte Pamela [email protected] 508-998-0215 Adams Town Clerk Meczywor Haley [email protected] 413-743-8300 Agawam City Clerk Gioscia Vincent [email protected] 413-786-0400 Alford Town Clerk Henden-Wilson Peggy Rae [email protected] 413-528-4536 Amesbury City Clerk Haggstrom Amanda [email protected] 978-388-8100 Amherst Town Clerk Martin Shavena [email protected] 413-259-3035 Andover Town Clerk Simko Austin [email protected] 978-623-8230 Aquinnah Town Clerk Camilleri Gabriella [email protected] 508-645-2300 Arlington Town Clerk Brazile Juliana H. [email protected] 781-316-3070 Ashburnham TOWN CLERK JOHNSON MICHELLE M [email protected] 978-827-4100 Ashby Town Clerk Jack Angela M. [email protected] 978-386-2424 Ashfield Town Clerk Fedorjaczenko Alexis [email protected] 413-628-4441 Ashland Town Clerk Ward Tara M. [email protected] 508-881-0100 Athol Town Clerk Burnham Nancy E. [email protected] 978-721-8445 Attleboro City Clerk Withers Steve [email protected] 508-223-2222 Auburn Town Clerk Gremo Debra A. [email protected] 508-832-7701 Avon Town Clerk Bessette Patricia [email protected] 508-588-0414 Ayer Town Clerk Copeland Susan E. -

Last Name First Name Middle Name Taken Test Registered License

As of 12:00 am on Thursday, December 14, 2017 Last Name First Name Middle Name Taken Test Registered License Richter Sara May Yes Yes Silver Matthew A Yes Yes Griffiths Stacy M Yes Yes Archer Haylee Nichole Yes Yes Begay Delores A Yes Yes Gray Heather E Yes Yes Pearson Brianna Lee Yes Yes Conlon Tyler Scott Yes Yes Ma Shuang Yes Yes Ott Briana Nichole Yes Yes Liang Guopeng No Yes Jung Chang Gyo Yes Yes Carns Katie M Yes Yes Brooks Alana Marie Yes Yes Richardson Andrew Yes Yes Livingston Derek B Yes Yes Benson Brightstar Yes Yes Gowanlock Michael Yes Yes Denny Racheal N No Yes Crane Beverly A No Yes Paramo Saucedo Jovanny Yes Yes Bringham Darren R Yes Yes Torresdal Jack D Yes Yes Chenoweth Gregory Lee Yes Yes Bolton Isabella Yes Yes Miller Austin W Yes Yes Enriquez Jennifer Benise Yes Yes Jeplawy Joann Rose Yes Yes Harward Callie Ruth Yes Yes Saing Jasmine D Yes Yes Valasin Christopher N Yes Yes Roegge Alissa Beth Yes Yes Tiffany Briana Jekel Yes Yes Davis Hannah Marie Yes Yes Smith Amelia LesBeth Yes Yes Petersen Cameron M Yes Yes Chaplin Jeremiah Whittier Yes Yes Sabo Samantha Yes Yes Gipson Lindsey A Yes Yes Bath-Rosenfeld Robyn J Yes Yes Delgado Alonso No Yes Lackey Rick Howard Yes Yes Brockbank Taci Ann Yes Yes Thompson Kaitlyn Elizabeth No Yes Clarke Joshua Isaiah Yes Yes Montano Gabriel Alonzo Yes Yes England Kyle N Yes Yes Wiman Charlotte Louise Yes Yes Segay Marcinda L Yes Yes Wheeler Benjamin Harold Yes Yes George Robert N Yes Yes Wong Ann Jade Yes Yes Soder Adrienne B Yes Yes Bailey Lydia Noel Yes Yes Linner Tyler Dane Yes Yes -

Language Revitalization As Rebuilding a Speech Community

Language Revitalization as Rebuilding a Speech Community MARIANNA DI PAOLO, LISA JOHNSON, SARAH ARNOFF, JENNIFER MITCHELL, DERRON BORDERS ICLDC- 4 HONOLULU, HI FEBRUARY 28, 2015 Wick R. Miller Collection Shoshoni Language Project, Who we are University of Utah Project began in 2002 Focus--to preserve and disseminate Miller’s collection NSF: #0418351, PI: M.J. Mixco, Co-PI: M. Di Paolo. 2004-2007. In 2007, focus shifted to revitalization Barrick Gold of North America Inc. PI: Marianna Di Paolo. 2007-2014. Shoshoni Language: Past & Future Uto- Wick Miller predicted that Aztecan Shoshoni would probably be gone by the late 20th century Northern Uto- Aztecan Few children were using it in the home by the late 1960’s Numic US Census estimate 2006- 2010 Central 2,211 Shoshoni speakers Numic 1,319 living in tribal communities Timbisha Shoshoni Comanche Shoshone/Goshute Communities What is a speech community? “A linguistic community is a social group which may be either From an anthropologist (Gumperz 1972:463) monolingual or multilingual, held together by frequency of social interaction patterns and set off from the surrounding areas by weaknesses in the lines of communication.” (Emphasis is ours.) What is a speech community? “The speech community is not defined From a sociolinguist by any marked agreement in the use of (Labov 1972:120) language elements, so much as by participation in a set of shared norms; these norms may be observed in overt types of evaluative behavior, and by the uniformity of abstract patterns of variation which are invariant in respect to particular levels of usage.” (Emphasis is ours.) What is a speech community? Themes Frequent interactions by members of the community using the language variety in question Shared language norms among community members, which influence their linguistic behavior People who derive a sense of identity from the community and together constitute the community Why do Languages don’t die out because of a languages die? lack of dictionaries, or grammars, or classes, or recordings. -

Conference on American Indian Languages Clearinghouse Newsletter

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 100 146 FL 006 141 AUTHOR Fidelholtz, James L., Ed. TITLE Conference on American Indian Languages Clearinghouse Newsletter. Vol. 2, No. 1. PUB DATE Jun 73 NOTE 21p.; Filmed from best available copy EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC Not Available from EDRS. PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS American Indian Culture; *American Indian Languages; Bibliographies; *Bilingual Education; Bilingualism; Language Instruction; Linguistics; *Newsletters; Second Language Learning ABSTRACT The first report in this issue, from Fort McPherson, MVT, concerns the ongoing work of transcribing, recording, and teaching Kutchin. In addition, there are reports concerning efforts in progress to preserve various Indian languages, among them Kwakiutl, Skagit, Shulkayn, Shoshoni, and Ojibway. Other investigations and courses in Alaskan native languagesare also mentioned. The status of the Tehlequah bilingual Cherokeeprogram is briefly reported, and the Navajo community-controlled bilingual program in Rough Rock, Arizona is described. A list of GPO publications involving Indian languages is provided, as is an annotated list of books available from other sources. Excerpts from the 'General Discussion of Papers by Mattingly and Halle' from 'Language by Ear and by Eye,' edited by James Kavanaugh and Ignatious Mattingly, are also provided. (LG) AMMO 110111more IggIgg% CONFERENCEL ON 1MERICAM INDIAN LANnUAGES CLEARINGHOUSEIMETTER =EN ..r...410.01arret. .1,1110.1 maw 1DIVIR: JAMES L.FIDELHOLTZ VOLVIE II,NO, 1 .1 WE, 173 PArE . U S DEPARTMENTOF HEALTH. NEADTUICOANTAILON HA,;. BEEN REPRO c DOCUMENT C f ROM 44S TWI TEuLTFEAR0EF xA( Tt Y AS GENE 1 DU( D oRIGIN EDUCATION tosoN ORGANIZATION THE Of, OPINiON Af,NC.ITpOiNTS Of VtF ALEXANDRA :"'AUSS MEMORIAL FUND ,.,4YED DO NOI NE( f. -

Announcements

227 Journal of Language Contact – THEMA 1 (2007): Contact: Framing its Theories and Descriptions ANNOUNCEMENTS Symposium Language Contact and the Dynamics of Language: Theory and Implications 10-13 May 2007 Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (Leipzig) Organizing institutions: Institut Universitaire de France : Chaire ‘Dynamique du langage et contact des langues’ (Nice) Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology: Department of Linguistics (Leipzig) Information and presentation: http://www.unice.fr/ChaireIUF-Nicolai/Symposium/Index_Symposium.html Thematic orientation Three themes are chosen. I. “‘Contact’: an ‘obvious fact ? A notion to be rethought?” The aim is to open theoretical reflection on the importance of ‘contact’ as a linguistic and anthropological phenomenon for the study of the evolution and dynamics of languages and of Language. II. “Contact, typology and evolution of languages: a perspective to be explored” Here the aim is to open discussion on what is constructed by ‘typology’. III. “Representation of the phenomena and the role of descriptors: a perspective to be established” In connection with the double requirement of theoretical reflection and empirical underpinning, the aim is to develop an epistemological reflection on the elaboration of knowledge in the domain of languages and Language. Titles of communications Peter Bakker (Aarhus) Rethinking structural diffusion Cécile Canut (Montpelllier) & Paroles et Agencements Jean-Marie Prieur (Montpelllier) Bernard Comrie (MPI-EVA, Leipzig & WALS tell us about the diffusion of structural features Santa Barbara) Nick Enfield (MPI, Nijmegen) Conceptual tools for a natural science of language (contact and change) Zygmunt Frajzyngier & Erin Shay (Boulder, Language-internal versus contact-induced change: the case of split Colorado) coding of person and number. -

Phonetic Description of a Three-Way Stop Contrast in Northern Paiute

UC Berkeley Phonology Lab Annual Report (2010) Phonetic description of a three-way stop contrast in Northern Paiute Reiko Kataoka Abstract This paper presents the phonetic description of a three-way phonemic contrast in the medial stops (lenis, fortis, and voiced fortis stops) of a southern dialect of Northern Paiute. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of VOT, closure duration, and voice quality was performed on field recordings of a female speaker from the 1950s. The findings include that: 1) voiced fortis stops are realized phonetically as voiceless unaspirated stops; 2) the difference between fortis and voiced fortis and between voiced fortis and lenis in terms of VOT is subtle; 3) consonantal duration is a robust acoustic characteristic differentiating the three classes of stops; 4) lenis stops are characterized by a smooth VC transition, while fortis stops often exhibit aspiration at the VC juncture, and voiced fortis stops exhibit occasional glottalization at the VC juncture. These findings suggest that the three-way contrast is realized by combination of multiple phonetic properties, particularly the properties that occur at the vowel-consonant boundary rather than the consonantal release. 1. Introduction Northern Paiute (NP) belongs to the Western Numic branch of the Uto-Aztecan language family and is divided into two main dialect groups: the northern group, Oregon Northern Paiute, and the southern group, Nevada Northern Paiute (Nichols 1974:4). Some of the southern dialects of Nevada Northern Paiute, known as Southern Nevada Northern Paiute (SNNP) (Nichols 1974), have a unique three-way contrast in the medial obstruent: ‗fortis‘, ‗lenis‘, and what has been called by Numic specialists the ‗voiced fortis‘ series. -

Thediachronyof Definitenessinnorth Germanic

The Diachrony of Definiteness in North Germanic Brill’s Studies in Historical Linguistics Series Editor Jóhanna Barðdal (Ghent University) Consulting Editor Spike Gildea (University of Oregon) Editorial Board Joan Bybee (University of New Mexico) – Lyle Campbell (University of Hawai’i Manoa) – Nicholas Evans (The Australian National University) Bjarke Frellesvig (University of Oxford) – Mirjam Fried (Czech Academy of Sciences) – Russel Gray (University of Auckland) – Tom Guldemann (Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin) – Alice Harris (University of Massachusetts) Brian D. Joseph (The Ohio State University) – Ritsuko Kikusawa (National Museum of Ethnology) – Silvia Luraghi (Università di Pavia) Joseph Salmons (University of Wisconsin) – Søren Wichmann (mpi/eva) volume 14 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/bshl The Diachrony of Definiteness in North Germanic By Dominika Skrzypek Alicja Piotrowska Rafał Jaworski leiden | boston This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the cc by-nc-nd 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the cc license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. The research presented in this monograph was financed by a research grant from the Polish National Science Centre (ncn) entitled Diachrony of definiteness in Scandinavian languages, number 2015/19/b/hs2/00143. -

Last Name First Name Middle Name Level of Certification Abbott Candy

All Indiana Certified Assessor Appraisers January 1, 2021 Please Note: After receiving an Assessor Appraiser designation, a person must earn continuing education hours during a two year cycle. A Level 1 Assessor Appraiser needs 30 hours of continuing education. Level 2 and Level 3 Assessor Appraisers need 45 hours of continuing education. After the first of each year continuing education for each individual is compiled. If the Department determines that an individual did not accrue enough continuing education hours during their two year cycle, a notification letter is sent and the person is placed on a list for revocation of their certification. A person is still considered certified until after the revocation hearing when the Department makes the decision to revoke a certification. Level of Last Name First Name Middle Name Certification Abbott Candy 2 Abrams Dawn 3 Acosta Audrey 2 Acra Megan 2 Adamaitis Renee 3 Adams Dionne 3 Adams Jason M. 3 Adams Robert E. 2 Affolder Judith E. 3 Agnew Robert Gray 3 Ahrens Muna 3 Ajamie, Sr. Stephen J. 2 Alberson Robin L. 3 Alexander Mark 3 Allen James E. 3 Allison Reid J. 3 Altherr Linda L. 2 Ambrose Matthew Richard 3 Ancevski Elena 2 Anderson Cori Anne 2 Anderson David 2 Anderson Joshua G. 3 Anderson Kenneth W. 3 Anderson Kim K. 3 Anderson Rebecca ' Becky' 3 Anderson Steven L. 2 Anderson Tim 3 Angniman Aketchi Marc 1 Antsaklis Leah-Melinda 'Lily' 2 Page 1 Archer Joshua T. 2 Archer Richard L. 3 Arion Sandy 2 Armbruster Dale 3 Arnold Kelli 3 Arocho Millie 3 Atkinson Benjamin 2 Aubrey Jennifer ' Jeni' 3 Austgen John K. -

Blended Grammar: Kumandene Tariana of Northwest Amazonia

DOI: 10.26346/1120-2726-169 Blended grammar: Kumandene Tariana of northwest Amazonia Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald Central Queensland University, Cairns, Australia <[email protected]> Kumandene Tariana, a North Arawak language, spoken by about 40 people in the community of Santa Terezinha on the Iauari river (tributary of the Vaupés River in north-west Amazonia), can be considered a new blended language. The Kumandene Tariana moved to their present location from the middle Vaupés about two generations ago. They now intermarry with the Baniwa Hohôdene, speakers of a closely related language. This agrees with the principle of ‘lin- guistic exogamy’ common to most indigenous people within the Vaupés River Basin linguistic area. With Baniwa as the majority language, Kumandene Tariana is endangered. The only other extant variety of Tariana is the Wamiarikune Tariana dialect which has undergone strong influence from Tucano, the major language of the region. As a result of their divergent development, Kumandene Tariana and Wamiarikune Tariana are not mutually intelligible. Over the past fifty years, speakers of Kumandene Tariana have acquired numerous Baniwa-like features in the grammar and lexicon. The extent of Baniwa impact on Kumandene Tariana varies depending on the speaker. Kumandene Tariana shares some similarities with other ‘blended’, or ‘merged’ languages. The influence of Baniwa is particularly instructive in the domain of verbal categories – negation, tense, aspect, and evidentiality. Keywords: Tariana, Arawak languages, Amazonian languages, blended lan- guages, multilingualism. 1. Colonial expansion and linguistic repertoires in Amazonia Lowland Amazonia is renowned for its linguistic diversity in terms of number of languages, their genetic affiliation, and their structural patterns.