Phonetic Description of a Three-Way Stop Contrast in Northern Paiute

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Phonetic Nature of Consonants in Modern Standard Arabic

www.sciedupress.com/elr English Linguistics Research Vol. 4, No. 3; 2015 The Phonetic Nature of Consonants in Modern Standard Arabic Mohammad Yahya Bani Salameh1 1 Tabuk University, Saudi Arabia Correspondence: Mohammad Yahya Bani Salameh, Tabuk University, Saudi Arabia. Tel: 966-58-0323-239. E-mail: [email protected] Received: June 29, 2015 Accepted: July 29, 2015 Online Published: August 5, 2015 doi:10.5430/elr.v4n3p30 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5430/elr.v4n3p30 Abstract The aim of this paper is to discuss the phonetic nature of Arabic consonants in Modern Standard Arabic (MSA). Although Arabic is a Semitic language, the speech sound system of Arabic is very comprehensive. Data used for this study were collocated from the standard speech of nine informants who are native speakers of Arabic. The researcher used himself as informant, He also benefited from three other Jordanians and four educated Yemenis. Considering the alphabets as the written symbols used for transcribing the phones of actual pronunciation, it was found that the pronunciation of many Arabic sounds has gradually changed from the standard. The study also discussed several related issues including: Phonetic Description of Arabic consonants, classification of Arabic consonants, types of Arabic consonants and distribution of Arabic consonants. Keywords: Modern Standard Arabic (MSA), Arabic consonants, Dialectal variation, Consonants distribution, Consonants classification. 1. Introduction The Arabic language is one of the most important languages of the world. With it is growing importance of Arab world in the International affairs, the importance of Arabic language has reached to the greater heights. Since the holy book Qura'n is written in Arabic, the language has a place of special prestige in all Muslim societies, and therefore more and more Muslims and Asia, central Asia, and Africa are learning the Arabic language, the language of their faith. -

Mimicry of Non-Distinctive Phonetic Differences Between Language Varieties *

Mimicry of Non-distinctive Phonetic Differences Between Language Varieties * James Emil Flege Ro bert M. Ham mond Unil'l

Gradient Phonemic Contrast in Nanjing Mandarin Keith Johnson (UC Berkeley) Yidan Song (Nanjing Normal University)

UC Berkeley Phonetics and Phonology Lab Annual Report (2016) Gradient phonemic contrast in Nanjing Mandarin Keith Johnson (UC Berkeley) Yidan Song (Nanjing Normal University) Abstract Sounds that are contrastive in a language are rated by listeners as being more different from each other than sounds that don’t occur in the language or sounds that are allophones of a single phoneme. The study reported in this paper replicates this finding and adds new data on the perceptual impact of learning a language with a new contrast. Two groups of speakers of the Nanjing dialect of Mandarin Chinese were tested. One group was older and had not been required to learn standard Mandarin as school children, while the other younger group had learned standard Mandarin in school. Nanjing dialect does not contrast [n] and [l], while standard Mandarin does. Listeners rated the similarity of naturally produced non-words presented in pairs, where the only difference between the tokens was the medial consonant. Pairs contrasting [n] and [l] were rated by older Nanjing speakers as if two [n] tokens or two [l] tokens had been presented, while these same pairs were rated by younger Nanjing speakers as noticeably different but not as different as pairs that contrast in their native language. Introduction The variety of Mandarin Chinese spoken in Nanjing does not have a contrast between [n] and [l] (Song, 2015), while the standard variety which is now taught in schools in Nanjing does have this contrast. Prior research has shown that speech perception is modulated by linguistic experience. Years of research has shown that listeners find it very difficult to perceive differences between sounds that are not contrastive in their language (Goto, 1971; Werker & Tees, 1984; Flege, 1995; Best et al., 2001). -

Introductory Phonology

3 More on Phonemes 3.1 Phonemic Analysis and Writing The question of phonemicization is in principle independent from the question of writing; that is, there is no necessary connection between letters and phonemes. For example, the English phoneme /e}/ can be spelled in quite a few ways: say /se}/, Abe /e}b/, main /me}n/, beige /be}è/, reggae /cryge}/, H /e}tà/. Indeed, there are languages (for example, Mandarin Chinese) that are written with symbols that do not correspond to phonemes at all. Obviously, there is at least a loose connection between alphabetic letters and phonemes: the designers of an alphabet tend to match up the written symbols with the phonemes of a language. Moreover, the conscious intuitions of speakers about sounds tend to be heavily influenced by their knowledge of spelling – after all, most literate speakers receive extensive training in how to spell during child- hood, but no training at all in phonology. Writing is prestigious, and our spoken pronunciations are sometimes felt to be imperfect realizations of what is written. This is reflected in the common occur- rence of spelling pronunciations, which are pronunciations that have no historical basis, but which arise as attempts to mimic the spelling, as in often [cÑftvn] or palm [pwlm]. In contrast, most linguists feel that spoken language is primary, and that written language is a derived system, which is mostly parasitic off the spoken language and is often rather artificial in character. Some reasons that support this view are that spoken language is far older than writing, it is acquired first and with greater ease by children, and it is the common property of our species, rather than of just an educated subset of it. -

Minimal Pair Approaches to Phonological Remediation

Minimal Pair Approaches to Phonological Remediation Jessica A. Barlow, Ph.D.,1 and Judith A. Gierut, Ph.D.2 ABSTRACT This article considers linguistic approaches to phonological reme- diation that emphasize the role of the phoneme in language. We discuss the structure and function of the phoneme by outlining procedures for de- termining contrastive properties of sound systems through evaluation of minimal word pairs. We then illustrate how these may be applied to a case study of a child with phonological delay. The relative effectiveness of treat- ment approaches that facilitate phonemic acquisition by contrasting pairs of sounds in minimal pairs is described. A hierarchy of minimal pair treat- ment efficacy emerges, as based on the number of new sounds, the number of featural differences, and the type of featural differences being intro- duced. These variables are further applied to the case study, yielding a range of possible treatment recommendations that are predicted to vary in their effectiveness. KEYWORDS: Phoneme, minimal pair, phonological remediation Learning Outcomes: As a result of this activity, the reader will be able to (1) analyze and recognize the con- trastive function of phonemes in a phonological system, (2) develop minimal pair treatment programs that aim to introduce phonemic contrasts in a child’s phonological system, and (3) discriminate between different types of minimal pair treatment programs and their relative effectiveness. Models of clinical treatment for children cognition given our need to understand how with functional phonological delays have been learning takes place in the course of interven- based on three general theoretical frameworks. tion. Still other approaches are grounded in Some models are founded on development linguistics because the problem at hand in- given that the population of concern involves volves the phonological system. -

Focus on Consonants: Prosodic Prominence and the Fortis-Lenis Contrast in English

237 Focus on Consonants: Prosodic Prominence and the Fortis-Lenis Contrast in English Míša Hejná & Anna Jespersen Aarhus University Abstract This study investigates the effects of intonational focus on the implementation of the fortis-lenis contrast. We analyse data from 5 speakers of different English dialects (Ocke’s colleagues), with the aim of examining the extent to which different correlates of the contrast are used by each speaker, and whether the contrast is implemented differently across different levels of focal prominence (narrow focus, broad focus, de-accentuation). The correlates examined include three measures often associated with the contrast (pre-obstruent vowel duration, consonant/ vowel durational ratio, rate of application of obstruent voicing), as well as a number of lesser-investigated phenomena. Firstly, we fi nd that individual speakers utilise different phonetic correlates to implement the fortis-lenis contrast. Secondly, focus affects several of these, with the biggest effect found with consonant/vowel ratio, and the smallest with obstruent voicing. 1. Introduction It has been frequently claimed that there is more variation in vowels than consonants (e.g. Bohn & Caudery, 2017, p. 63), possibly because “consonantal variation (in British English at least) tends to be used less as a way of marking local identity than vocalic variation does” (Trousdale, 2010, p. 116). An alternative claim may be that “[c]onsonantal features have been studied far less rigorously than vowel features” (Cox & Palethorpe, 2007, p. 342, who comment on the state of consonantal variation studies in Australian English; but see also Su, 2007, p. 6). Anne Mette Nyvad, Michaela Hejná, Anders Højen, Anna Bothe Jespersen & Mette Hjortshøj Sørensen (Eds.), A Sound Approach to Language Matters – In Honor of Ocke-Schwen Bohn (pp. -

High-Elevation Prehistoric Land Use in the Central Sierra Nevada, Yosemite National Park, California

High-Elevation Prehistoric Land Use in the Central Sierra Nevada, Yosemite National Park, California Suzanna Theresa Montague B.A., Colorado College, Colorado Springs, 1982 THESIS Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in ANTHROPOLOGY at CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, SACRAMENTO SPRING 2010 High-Elevation Prehistoric Land Use in the Central Sierra Nevada, Yosemite National Park, California A Thesis by Suzanna Theresa Montague Approved by: __________________________________, Committee Chair Mark E. Basgall, Ph.D. __________________________________, Second Reader David W. Zeanah, Ph.D. ____________________________ Date ii Student: Suzanna Theresa Montague I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the thesis. __________________________, ___________________ Michael Delacorte, Ph.D, Graduate Coordinator Date Department of Anthropology iii Abstract of High-Elevation Prehistoric Land Use in the Central Sierra Nevada, Yosemite National Park, California by Suzanna Theresa Montague The study investigated pre-contact land use on the western slope of California’s central Sierra Nevada, within the subalpine and alpine zones of the Tuolumne River watershed, Yosemite National Park. Relying on existing data for 373 archaeological sites and minimal surface materials collected for this project, examination of site constituents and their presumed functions in light of geography and chronology indicated two distinctive archaeological patterns. First, limited-use sites—lithic scatters thought to represent hunting, travel, or obsidian procurement activities—were most prevalent in pre- 1500 B.P. contexts. Second, intensive-use sites, containing features and artifacts believed to represent a broader range of activities, were most prevalent in post-1500 B.P. -

Student Magazine Historic Photograph of Siletz Feather Dancers in Newport for the 4Th of July Celebration in the Early 1900S

STUDENT MAGAZINE Historic photograph of Siletz Feather dancers in Newport for the 4th of July celebration in the early 1900s. For more information, see page 11. (Photo courtesy of the CT of the Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw). The Oregon Historical Society thanks contributing tradition bearers and members of the Nine Federally Recognized Tribes for sharing their wisdom and preserving their traditional lifeways. Text by: Lisa J. Watt, Seneca Tribal Member Carol Spellman, Oregon Historical Society Allegra Gordon, intern Paul Rush, intern Juliane Schudek, intern Edited by: Eliza Canty-Jones Lisa J. Watt Marsha Matthews Tribal Consultants: Theresa Peck, Burns Paiute Tribe David Petrie, Confederated Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Indians Angella McCallister, Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community Deni Hockema, Coquille Tribe, Robert Kentta, Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians Susan Sheoships, Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation and Museum at Tamástslikt Cultural Institute Myra Johnson, Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation Louis La Chance, Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Tribe of Indians Perry Chocktoot, The Klamath Tribes Photographs provided by: The Nine Federally Recognized Tribes Oregon Council for the Humanities, Cara Unger-Gutierrez and staff Oregon Historical Society Illustration use of the Plateau Seasonal Round provided by Lynn Kitagawa Graphic Design: Bryan Potter Design Cover art by Bryan Potter Produced by the Oregon Historical Society 1200 SW Park Avenue, Portland, OR 97205 Copyright -

Pre-Fortis Shortening in Fluent Read Speech: a Comparison of Czech and Native Speakers of English

2014 ACTA UNIVERSITATIS CAROLINAE PAG. 91–100 PHILOLOGICA 1 / PHONETICA PRAGENSIA XIII PRE-FORTIS SHORTENING IN FLUENT READ SPEECH: A COMPARISON OF CZECH AND NATIVE SPEAKERS OF ENGLISH DITA FEJLOVÁ ABSTRACT This paper inspects the details of a phenomenon called pre-fortis short- ening, the existence of which is widely acknowledged by phoneticians. It occurs in VC sequences where the final consonant is voiceless (fortis). For English, the difference in the duration before fortis and lenis consonants is recognized as a cue of the consonant’s voicing, since the actual voicing tends to be missing. The study compares the extent to which pre-fortis shortening is employed by native speakers of English and by Czech stu- dents of English with different degrees of foreign accent. The results sug- gest that the difference in the duration of pre-fortis and pre-lenis vowels is considerably lower in connected speech than in previously reported results, even in native speakers, with the difference more pronounced in long (tense) vowels. Key words: vowel duration, fortis and lenis consonants, pre-fortis short- ening, Czech English 1. Introduction The duration of individual segments in speech has been researched from several perspectives. Leaving aside higher-level cognitive decisions determined by the commu- nicative intent, it is possible to identify several factors which affect the ultimate duration of vowels and consonants in connected speech. The following paragraphs will focus on vowels only, not only because it is their duration that will be investigated in this paper, but also because studies on vowels are more numerous. Van Santen (1992) lists seven factors which have quantitative effects on vowel durations, some of which will be discussed here in some detail. -

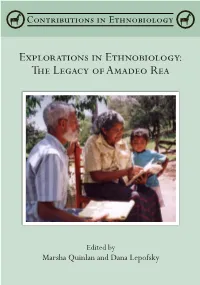

Explorations in Ethnobiology: the Legacy of Amadeo Rea

Explorations in Ethnobiology: The Legacy of Amadeo Rea Edited by Marsha Quinlan and Dana Lepofsky Explorations in Ethnobiology: The Legacy of Amadeo Rea Edited by Marsha Quinlan and Dana Lepofsky Copyright 2013 ISBN-10: 0988733013 ISBN-13: 978-0-9887330-1-5 Library of Congress Control Number: 2012956081 Society of Ethnobiology Department of Geography University of North Texas 1155 Union Circle #305279 Denton, TX 76203-5017 Cover photo: Amadeo Rea discussing bird taxonomy with Mountain Pima Griselda Coronado Galaviz of El Encinal, Sonora, Mexico, July 2001. Photograph by Dr. Robert L. Nagell, used with permission. Contents Preface to Explorations in Ethnobiology: The Legacy of Amadeo Rea . i Dana Lepofsky and Marsha Quinlan 1 . Diversity and its Destruction: Comments on the Chapters . .1 Amadeo M. Rea 2 . Amadeo M . Rea and Ethnobiology in Arizona: Biography of Influences and Early Contributions of a Pioneering Ethnobiologist . .11 R. Roy Johnson and Kenneth J. Kingsley 3 . Ten Principles of Ethnobiology: An Interview with Amadeo Rea . .44 Dana Lepofsky and Kevin Feeney 4 . What Shapes Cognition? Traditional Sciences and Modern International Science . .60 E.N. Anderson 5 . Pre-Columbian Agaves: Living Plants Linking an Ancient Past in Arizona . .101 Wendy C. Hodgson 6 . The Paleobiolinguistics of Domesticated Squash (Cucurbita spp .) . .132 Cecil H. Brown, Eike Luedeling, Søren Wichmann, and Patience Epps 7 . The Wild, the Domesticated, and the Coyote-Tainted: The Trickster and the Tricked in Hunter-Gatherer versus Farmer Folklore . .162 Gary Paul Nabhan 8 . “Dog” as Life-Form . .178 Eugene S. Hunn 9 . The Kasaga’yu: An Ethno-Ornithology of the Cattail-Eater Northern Paiute People of Western Nevada . -

Northern Paiute of California, Idaho, Nevada and Oregon

טקוּפה http://family.lametayel.co.il/%D7%9E%D7%A1%D7%9F+%D7%A4%D7%A8%D7%A0%D7 %A1%D7%99%D7%A1%D7%A7%D7%95+%D7%9C%D7%9C%D7%90%D7%A1+%D7%9 5%D7%92%D7%90%D7%A1 تاكوبا Τακόπα The self-sacrifice on the tree came to them from a white-bearded god who visited them 2,000 years ago. He is called different names by different tribes: Tah-comah, Kate-Zahi, Tacopa, Nana-bush, Naapi, Kul-kul, Deganaweda, Ee-see-cotl, Hurukan, Waicomah, and Itzamatul. Some of these names can be translated to: the Pale Prophet, the bearded god, the Healer, the Lord of Water and Wind, and so forth. http://www.spiritualjourneys.com/article/diary-entry-a-gift-from-an-indian-spirit/ Chief Tecopa - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chief_Tecopa Chief Tecopa From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Chief Tecopa (c.1815–1904) was a Native American leader, his name means wildcat. [1] Chief Tecopa was a leader of the Southern Nevada tribe of the Paiute in the Ash Meadows and Pahrump areas. In the 1840s Tecopa and his warriors engaged the expedition of Kit Carson and John C. Fremont in a three-day battle at Resting Springs.[2] Later on in life Tecopa tried to maintain peaceful relations with the white settlers to the region and was known as a peacemaker. [3] Tecopa usually wore a bright red band suit with gold braid and a silk top hat. Whenever these clothes wore out they were replaced by the local white miners out of gratitude for Tecopa's help in maintaining peaceful relations with the Paiute. -

Introduction

Introduction This dictionary is primarily of the Death Valley variety of what has come to be known in the linguistic and anthropological literature in recent years as Panamint (e.g., Freeze and Iannucci 1979; Lamb 1958 and 1964; McLaughlin 1987; Miller 1984), or sometimes Panamint Shoshone (Miller et al. 1971). In the nineteenth century and up to the middle of this century, it was often called Coso (sometimes spelled Koso) or Coso Shoshone (e.g., Kroeber 1925; Lamb 1958). In aboriginal times and even well into this century, Panamint was spoken by small bands of people living in southeastern California and extreme southwestern Nevada in the valleys and mountain ranges east of the Sierra Nevada. Thus, Panamint territory included the southern end of Owens Valley around Owens Lake, the Coso Range and Little Lake area, the southern end of Eureka Valley, Saline Valley and the eastern slopes of the Inyo Mountains, the Argus Range, northern Panamint Valley and the Panamint Mountains, northern and central Death Valley, the Grapevine Mountains and Funeral Range, the Amargosa Desert and area around Beatty, Nevada (see Maps, pp. x-xi; also Kroeber 1925:589-90 and Steward 1938:70ff). Panamint is closely related to Shoshone proper, spoken immediately to the northeast of it, and to Comanche, spoken now in Oklahoma but formerly in the central and southern Great Plains. Together these three closely related languages comprise the Central Numic branch of the Numic family of the xv xvi INTRODUCTION uto-Aztecan stock of American Indian languages (see Kaufman and Campbell 1981, Lamb 1964, and Miller 1984).