Explorations in Ethnobiology: the Legacy of Amadeo Rea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barking up the Same Tree: a Comparison of Ethnomedicine and Canine Ethnoveterinary Medicine Among the Aguaruna Kevin a Jernigan

Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine BioMed Central Research Open Access Barking up the same tree: a comparison of ethnomedicine and canine ethnoveterinary medicine among the Aguaruna Kevin A Jernigan Address: COPIAAN (Comité de Productores Indígenas Awajún de Alto Nieva), Bajo Cachiaco, Peru Email: Kevin A Jernigan - [email protected] Published: 10 November 2009 Received: 9 July 2009 Accepted: 10 November 2009 Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 2009, 5:33 doi:10.1186/1746-4269-5-33 This article is available from: http://www.ethnobiomed.com/content/5/1/33 © 2009 Jernigan; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Background: This work focuses on plant-based preparations that the Aguaruna Jivaro of Peru give to hunting dogs. Many plants are considered to improve dogs' sense of smell or stimulate them to hunt better, while others treat common illnesses that prevent dogs from hunting. This work places canine ethnoveterinary medicine within the larger context of Aguaruna ethnomedicine, by testing the following hypotheses: H1 -- Plants that the Aguaruna use to treat dogs will be the same plants that they use to treat people and H2 -- Plants that are used to treat both people and dogs will be used for the same illnesses in both cases. Methods: Structured interviews with nine key informants were carried out in 2007, in Aguaruna communities in the Peruvian department of Amazonas. -

Lesser Prairie-Chicken Habitat Map for Portions of Eastern New Mexico

________________________________________________________________________ Lesser Prairie-Chicken Habitat Map for Portions of Eastern New Mexico ________________________________________________________________________ 16 November 2005 Lesser Prairie-Chicken Habitat Map for 1 Portions of Eastern New Mexico Paul Neville, Teri Neville, and Kristine Johnson2 ABSTRACT The purpose of this project was to provide a map depicting the extent and location of lesser prairie-chicken habitat in New Mexico. The 923,441 ha (2,281,868 ac) study area includes most of the remaining occupied habitat for the lesser prairie-chicken in the state. We used field data in conjunction with satellite imagery and aerial photography to create a vegetation map. We classified the map according to plant associations and subsequently regrouped it into map units that incorporated landforms, to reflect the habitat requirements of lesser prairie-chickens. We performed GIS analyses incorporating vegetation type, patch size, and fragmentation to identify areas of high quality lesser prairie-chicken habitat. These analyses demonstrate that only three places within the mapped area contain large patches of suitable habitat, and one of those is south of US 380, where LPCH populations are already sparse and scattered. The GIS analyses also indicate that the vast majority of high-quality vegetation types occur in patches smaller than 3200 ha, rendering them by most definitions below the minimum size required by LPCH. Used in combination with GIS analysis and current LPCH population data, the map represents a powerful management, planning, and monitoring tool. 1 Draft Final report submitted 31 August 2005 in partial fulfillment of Task Order 5 to Cooperative Agreement No. GDA010009 between Natural Heritage New Mexico at the University of New Mexico and Bureau of Land Management; Work Order No. -

A Comparative Study of Ethnobotanical Taxonomies: Swahili and Digo

A Comparative Study of Ethnobotanical Taxonomies: Swahili and Digo Steve Nicolle This paper explores how members of two East African language groups, with similar languages and cultures, classify the plant world. Differences primarily concern which parameters (e.g., size, uses, and longevity) determine how plant species are categorized. I show how linguistically similar classifications can obscure significant differences in folk botanical taxonomies. Introduction The early classic studies from which the present paper has developed began with the seminal ethnoscience work of the cognitive anthropologists Harold Conklin (1954, 1962), Charles Frake (1969), and Ward Goodenough (1957). Later influential ethnobiological taxonomic studies were done by Cecil Brown (1977, 1979), Terence Hays (1976), and especially by Brent Berlin and his co-authors (e.g., Berlin, Breedlove and Raven 1968, 1969, 1973, etc.) and peaking with Berlin's magnum opus (1992). Early methodologies for eliciting ethnobotanical folk taxonomies, now used as a standard, are found in Black (1969) and in Werner and Fenton's "card sorting" (1973); both methods were used in the present study. Later critics refined the endeavor of folk botanical classification as they encountered problems in "intra-cultural variability" among neighbors in the same speech community (e.g., Gal 1973, Pelto and Pelto 1975, Gardner 1976, Headland 1981, 1983, and several other papers in a special 1975 issue of American Ethnologist vol. 2, no. 1, titled "Intra-cultural Variability"). The present author found some of these problems of disagreements between informants as well. This brief study looks at the way plants are classified by speakers of two Northeast Coast Bantu languages, Swahili and Digo. -

Interspecific Relationships Affecting Endangered Species Recognized by O'odham and Comcaac Cultures

Interspecific Relationships Affecting Endangered Species Recognized by O'Odham and Comcáac Cultures Author(s): Gary Paul Nabhan Source: Ecological Applications, Vol. 10, No. 5 (Oct., 2000), pp. 1288-1295 Published by: Ecological Society of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2641284 Accessed: 03/11/2010 16:20 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=esa. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Ecological Society of America is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Ecological Applications. http://www.jstor.org 1288 INVITED FEATURE Ecological Applications Vol. 10, No. -

Pima County Plant List (2020) Common Name Exotic? Source

Pima County Plant List (2020) Common Name Exotic? Source McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Abies concolor var. concolor White fir Devender, T. R. (2005) McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Abies lasiocarpa var. arizonica Corkbark fir Devender, T. R. (2005) Abronia villosa Hariy sand verbena McLaughlin, S. (1992) McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Abutilon abutiloides Shrubby Indian mallow Devender, T. R. (2005) Abutilon berlandieri Berlandier Indian mallow McLaughlin, S. (1992) Abutilon incanum Indian mallow McLaughlin, S. (1992) McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Abutilon malacum Yellow Indian mallow Devender, T. R. (2005) Abutilon mollicomum Sonoran Indian mallow McLaughlin, S. (1992) Abutilon palmeri Palmer Indian mallow McLaughlin, S. (1992) Abutilon parishii Pima Indian mallow McLaughlin, S. (1992) McLaughlin, S. (1992); UA Abutilon parvulum Dwarf Indian mallow Herbarium; ASU Vascular Plant Herbarium Abutilon pringlei McLaughlin, S. (1992) McLaughlin, S. (1992); UA Abutilon reventum Yellow flower Indian mallow Herbarium; ASU Vascular Plant Herbarium McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Acacia angustissima Whiteball acacia Devender, T. R. (2005); DBGH McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Acacia constricta Whitethorn acacia Devender, T. R. (2005) McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Acacia greggii Catclaw acacia Devender, T. R. (2005) Acacia millefolia Santa Rita acacia McLaughlin, S. (1992) McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Acacia neovernicosa Chihuahuan whitethorn acacia Devender, T. R. (2005) McLaughlin, S. (1992); UA Acalypha lindheimeri Shrubby copperleaf Herbarium Acalypha neomexicana New Mexico copperleaf McLaughlin, S. (1992); DBGH Acalypha ostryaefolia McLaughlin, S. (1992) Acalypha pringlei McLaughlin, S. (1992) Acamptopappus McLaughlin, S. (1992); UA Rayless goldenhead sphaerocephalus Herbarium Acer glabrum Douglas maple McLaughlin, S. (1992); DBGH Acer grandidentatum Sugar maple McLaughlin, S. (1992); DBGH Acer negundo Ashleaf maple McLaughlin, S. -

Traffic.Org/Home/2015/12/4/ Thousands-Of-Birds-Seized-From-East-Java-Port.Html

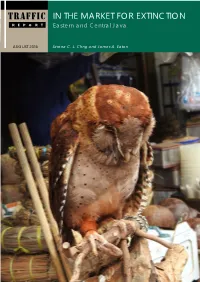

TRAFFIC IN THE MARKET FOR EXTINCTION REPORT Eastern and Central Java AUGUST 2016 Serene C. L. Chng and James A. Eaton TRAFFIC Report: In The Market for Extinction: Eastern and Central Java 1 TRAFFIC REPORT TRAFFIC, the wild life trade monitoring net work, is the leading non-governmental organization working globally on trade in wild animals and plants in the context of both biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. TRAFFIC is a strategic alliance of WWF and IUCN. Reprod uction of material appearing in this report requires written permission from the publisher. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organizations con cern ing the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views of the authors expressed in this publication are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect those of TRAFFIC, WWF or IUCN. Published by TRAFFIC. Southeast Asia Regional Office Unit 3-2, 1st Floor, Jalan SS23/11 Taman SEA, 47400 Petaling Jaya Selangor, Malaysia Telephone : (603) 7880 3940 Fax : (603) 7882 0171 Copyright of material published in this report is vested in TRAFFIC. © TRAFFIC 2016. ISBN no: 978-983-3393-50-3 UK Registered Charity No. 1076722. Suggested citation: Chng, S.C.L. and Eaton, J.A. (2016). In the Market for Extinction: Eastern and Central Java. TRAFFIC. Petaling Jaya, Selangor, Malaysia. Front cover photograph: An Oriental Bay Owl Phodilus badius displayed for sale at Malang Bird Market Credit: Heru Cahyono/TRAFFIC IN THE MARKET FOR EXTINCTION Eastern and Central Java Serene C. -

The Phylogenetic Significance of Fruit Structural Variation in the Tribe Heteromorpheae (Apiaceae)

Pak. J. Bot., 48(1): 201-210, 2016. THE PHYLOGENETIC SIGNIFICANCE OF FRUIT STRUCTURAL VARIATION IN THE TRIBE HETEROMORPHEAE (APIACEAE) MEI LIU1*, BEN-ERIK VAN WYK2, PATRICIA M. TILNEY2, GREGORY M. PLUNKETT3 AND PORTER P. LOWRY II4,5 AND ANTHONY R. MAGEE6 1Department of Biology, Harbin Normal University, Harbin, People’s Republic of China 2Department of Botany and Plant Biotechnology, University of Johannesburg, Auckland Park, Johannesburg, South Africa 3Cullman Program for Molecular Systematics, The New York Botanical Garden, Bronx, New York, United States of America 4Missouri Botanical Garden, Saint Louis, Missouri, United States of America 5Département Systématique et Evolution (UMR 7205) Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, CP 39, 57 rue Cuvier, 75213 Paris CEDEX 05, France 6South African National Biodiversity Institute, Compton Herbarium, Private Bag X7, Claremont 7735, South Africa *Correspondence author’s e-mail: [email protected]; Tel: +86 451 8806 0576; Fax: +86 451 8806 0575 Abstract Fruit structure of Apiaceae was studied in 19 species representing the 10 genera of the tribe Heteromorpheae. Our results indicate this group has a woody habit, simple leaves, heteromorphic mericarps with lateral wings. fruits with bottle- shaped or bulging epidermal cells which have thickened and cutinized outer wall, regular vittae (one in furrow and two in commissure) and irregular vittae (short, dwarf, or branching and anatosmosing), and dispersed druse crystals. However, lateral winged mericarps, bottle-shaped epidermal cells, and branching and anatosmosing vittae are peculiar in the tribe Heteromorpheae of Apioideae sub family. Although many features share with other early-diverging groups of Apiaceae, including Annesorhiza clade, Saniculoideae sensu lato, Azorelloideae, Mackinlayoideae, as well as with Araliaceae. -

Designations for Individual Genomes and Chromosomes in Gossypium WANG Kunbo1*, WENDEL Jonathan F.2 and HUA Jinping3

WANG et al. Journal of Cotton Research (2018) 1:3 Journal of Cotton Research https://doi.org/10.1186/s42397-018-0002-1 REVIEW Open Access Designations for individual genomes and chromosomes in Gossypium WANG Kunbo1*, WENDEL Jonathan F.2 and HUA Jinping3 Abstract Gossypium, as the one of the biggest genera, the most diversity, and the highest economic value in field crops, is assuming an increasingly important role in studies on plant taxonomy, polyploidization, phylogeny, cytogenetics, and genomics. Here we update and provide a brief summary of the emerging picture of species relationships and diversification, and a set of the designations for individual genomes and chromosomes in Gossypium. This cytogenetic and genomic nomenclature will facilitate comparative studies worldwide, which range from basic taxonomic exploration to breeding and germplasm introgression. Keywords: Nomenclature, Individual genome, Individual chromosome, Gossypium Because of its diversity and economic significance, the cotton diversity, from consisting of only a single species (F gen- genus (Gossypium) has been subjected to decades of taxo- ome) to larger genome groups containing more than a nomic, cytogenetic, and phylogenetic analyses. Accordingly, dozen species each (D, K). The important allopolyploid a reasonably well-documented phylogenetic and taxonomic clade, which includes G. hirsutum and G. barbadense,con- understanding has developed, as recently summarized tains 7 species, including two described only in the last (Wendel and Grover 2015). Work published since that time 10 years (G.ekmanianum,G.stephensii) (Krapovickas and also supports the emerging picture of species relationships Seijo 2008; Gallagher et al. 2017). and diversification (Grover et al. 2015a, 2015b;Chenetal. Many Gossypium species are taxonomically well- 2016; Gallagher et al. -

A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum Pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, Or Independent Domestication

UC Davis UC Davis Previously Published Works Title A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, or Independent Domestication Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1v84t8z1 Journal KIVA, 83(4) ISSN 0023-1940 Authors Graham, AF Adams, KR Smith, SJ et al. Publication Date 2017-10-02 DOI 10.1080/00231940.2017.1376261 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California KIVA Journal of Southwestern Anthropology and History ISSN: 0023-1940 (Print) 2051-6177 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ykiv20 A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, or Independent Domestication Anna F. Graham, Karen R. Adams, Susan J. Smith & Terence M. Murphy To cite this article: Anna F. Graham, Karen R. Adams, Susan J. Smith & Terence M. Murphy (2017): A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, or Independent Domestication, KIVA, DOI: 10.1080/00231940.2017.1376261 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00231940.2017.1376261 View supplementary material Published online: 12 Oct 2017. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ykiv20 Download by: [184.99.134.102] Date: 12 October 2017, At: 06:14 kiva, 2017, 1–29 A New Record of Domesticated Little Barley (Hordeum pusillum Nutt.) in Colorado: Travel, Trade, or Independent Domestication Anna F. Graham1, Karen R. Adams2, Susan J. Smith3, and Terence M. -

Appendix B References

Final Tier 1 Environmental Impact Statement and Preliminary Section 4(f) Evaluation Appendix B, References July 2021 Federal Aid No. 999-M(161)S ADOT Project No. 999 SW 0 M5180 01P I-11 Corridor Final Tier 1 EIS Appendix B, References 1 This page intentionally left blank. July 2021 Project No. M5180 01P / Federal Aid No. 999-M(161)S I-11 Corridor Final Tier 1 EIS Appendix B, References 1 ADEQ. 2002. Groundwater Protection in Arizona: An Assessment of Groundwater Quality and 2 the Effectiveness of Groundwater Programs A.R.S. §49-249. Arizona Department of 3 Environmental Quality. 4 ADEQ. 2008. Ambient Groundwater Quality of the Pinal Active Management Area: A 2005-2006 5 Baseline Study. Open File Report 08-01. Arizona Department of Environmental Quality Water 6 Quality Division, Phoenix, Arizona. June 2008. 7 https://legacy.azdeq.gov/environ/water/assessment/download/pinal_ofr.pdf. 8 ADEQ. 2011. Arizona State Implementation Plan: Regional Haze Under Section 308 of the 9 Federal Regional Haze Rule. Air Quality Division, Arizona Department of Environmental Quality, 10 Phoenix, Arizona. January 2011. https://www.resolutionmineeis.us/documents/adeq-sip- 11 regional-haze-2011. 12 ADEQ. 2013a. Ambient Groundwater Quality of the Upper Hassayampa Basin: A 2003-2009 13 Baseline Study. Open File Report 13-03, Phoenix: Water Quality Division. 14 https://legacy.azdeq.gov/environ/water/assessment/download/upper_hassayampa.pdf. 15 ADEQ. 2013b. Arizona Pollutant Discharge Elimination System Fact Sheet: Construction 16 General Permit for Stormwater Discharges Associated with Construction Activity. Arizona 17 Department of Environmental Quality. June 3, 2013. 18 https://static.azdeq.gov/permits/azpdes/cgp_fact_sheet_2013.pdf. -

Largest Species, Citheronia Splendens Sinaloensis (Hoffmann) and Ea Cles Oslari Rothschild, Is Poorly Known

Journal of the Lepidopterists' Society 40(4), 1986, 264- 270 BIOLOGY AND IMMATURE STAGES OF CITHERONIA SPLENDENS SINALOENSIS AND EACLES OSLARI IN ARIZONA (SATURNIIDAE) PAUL M. TUSKES 7900 Cambridge IllD, Houston, Texas 77054 ABSTRACT. Citheronia splendens sinaloensis and Eacles oslari occur in Cochise, Pima, and Santa Cruz counties in southern Arizona. Both species have one generation per year. The flight season of E. oslari extends from early June to mid-August, and the larval host plants include Quercus species. The flight season of C. splendens extends from July to mid-August, and the larval host plants include wild cotton, manzanita, and New Mexico evergreen sumac. The immature stages are described for the first time. The citheroniine fauna of Arizona is unique in that all seven species are primarily of Mexican origin (Tuskes 1985). The biology of the two largest species, Citheronia splendens sinaloensis (Hoffmann) and Ea cles oslari Rothschild, is poorly known. Ferguson (1971) illustrated the adults, summarized existing information, and indicated that their im mature stages were undescribed. The purpose of this paper is to de scribe the immature stages of both species and to present additional biological and distributional information. Citheronia splendens sinaloensis (Figs. 1-4) Citheronia splendens sinaloensis is the only member of the genus presently known to occur in Arizona. Citheronia mexicana G. & R. occurs just south of Arizona, in Sonora, Mexico. Although reported from Arizona before the turn of the century, there are no recent United States records. Citheronia regalis (F.) and C. sepulcralis (Druce) are common in the eastern or central United States but do not occur farther west than central Texas. -

Yerba Buena Chapter – CNPS

PROGRAMS Everyone is welcome to attend membership meetings in the Recreation Room of the San Francisco YERBA County Fair Building (SFCFB) at 9 th Avenue and Lincoln Way in Golden Gate Park. The #71 and #44 buses stop at the building. The N-Judah, #6, #43, and #66 lines stop within 2 blocks. Before our BUENA programs, we take our speakers to dinner at Changs Kitchen, 1030 Irving Street, between 11 th and 12 th Avenues. Join us for good Chinese food and interesting conversation. Meet at the restaurant at 5:30 pm. RSVP appreciated but not required - call Jake Sigg at 415-731-3028 if you wish to notify. THURSDAY JUNE 7, 7:30pm Tiny and Tough: Rare Plants of Mount Tams Serpentine Barrens Speaker: Rachel Kesel Among the rare vegetation types found on Mount Tamalpais, serpentine barrens present plants with NEW S some of the harshest soil conditions for growth. For much of the year it appears that these areas of pretty blue rock and soil are indeed barren. However, several rare annual plants make a living in this habitat, including some endemic to the Mount Tam area. In addition to serpentine barrens, adjacent THE YERBA BUENA chaparral and grasslands host rare perennial species equally as tough as the tiny annuals, if far larger in CHAPTER OF THE size. CALIFORNIA Land managers across the mountain are monitoring a suite of ten rare plants found in serpentine barrens NATIVE PLANT to better understand their distributions and population fluctuations over time. Known as the Serpentine SOCIETY FOR Endemic Occupancy Project, this effort is one of many cross-jurisdictional endeavors of the One Tam initiative.