Thediachronyof Definitenessinnorth Germanic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Revellers at New Year’S Eve 2018 – the Night Is Yours

AUSTRALIAN BROADCASTING CORPORATION ANNUAL REPORT 2019 Revellers at New Year’s Eve 2018 – The Night is Yours. Image: Jared Leibowtiz Cover: Dianne Appleby, Yawuru Cultural Leader, and her grandson Zeke 11 September 2019 The Hon Paul Fletcher MP Minister for Communications, Cyber Safety and the Arts Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Dear Minister The Board of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation is pleased to present its Annual Report for the year ended 30 June 2019. The report was prepared for section 46 of the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013, in accordance with the requirements of that Act and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation Act 1983. It was approved by the Board on 11 September 2019 and provides a comprehensive review of the ABC’s performance and delivery in line with its Charter remit. The ABC continues to be the home and source of Australian stories, told across the nation and to the world. The Corporation’s commitment to innovation in both storytelling and broadcast delivery is stronger than ever, as the needs of its audiences rapidly evolve in line with technological change. Australians expect an independent, accessible public broadcasting service which produces quality drama, comedy and specialist content, entertaining and educational children’s programming, stories of local lives and issues, and news and current affairs coverage that holds power to account and contributes to a healthy democratic process. The ABC is proud to provide such a service. The ABC is truly Yours. Sincerely, Ita Buttrose AC OBE Chair Letter to the Minister iii ABC Radio Melbourne Drive presenter Raf Epstein. -

The Influence of Old Norse on the English Language

Antonius Gerardus Maria Poppelaars HUSBANDS, OUTLAWS AND KIDS: THE INFLUENCE OF OLD NORSE ON THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE HUSBANDS, OUTLAWS E KIDS: A INFLUÊNCIA DO NÓRDICO ANTIGO NA LÍNGUA INGLESA Antonius Gerardus Maria Poppelaars1 Abstract: What have common English words such as husbands, outlaws and kids and the sentence they are weak to do with Old Norse? Yet, all these examples are from Old Norse, the Norsemen’s language. However, the Norse influence on English is underestimated as the Norsemen are viewed as barbaric, violent pirates. Also, the Norman occupation of England and the Great Vowel Shift have obscured the Old Norse influence. These topics, plus the Viking Age, the Scandinavian presence in England, as well as the Old Norse linguistic influence on English and the supposed French influence of the Norman invasion will be described. The research for this etymological article was executed through a descriptive- qualitative approach. Concluded is that the Norsemen have intensively influenced English due to their military supremacy and their abilities to adaptation. Even the French-Norman French language has left marks on English. Nowadays, English is a lingua franca, leading to borrowings from English to many languages, which is often considered as invasive. But, English itself has borrowed from other languages, maintaining its proper character. Hence, it is hoped that this article may contribute to a greater acknowledgement of the Norse influence on English and undermine the scepticism towards the English language as every language has its importance. Keywords: Old Norse Loanwords, English Language, Viking Age, Etymology. Resumo: O que têm palavras inglesas comuns como husbands, outlaws e kids e a frase they are weak a ver com os Nórdicos? Todos esses exemplos são do nórdico antigo, a língua dos escandinavos. -

Project Catalyst Magazine 2018

PROJECT CATALYST 2018 – THE EVOLUTION OF INNOVATION – HARVESTING IDEAS IN SUGAR TEN YEARS HARVESTING IDEAS FOSTERING INNOVATION CORAL & CANDY Catalyst growers inspiring The innovation challenge EMBRACING TECHNOLOGY next gen to 2030 Why farmers need data Image: Jeppersen Farm visit with Coca-Cola, WWF and Catalyst growers Mackay. TEN YEARS As we meet again for Project Catalyst Forum They say it takes a village to raise a child flow freely across mill and regional boundaries – 2018, we reflect on 10 years since a group of well I think it takes a community to deliver a this is part of the glue that holds our community forward thinking growers and representatives program like Project Catalyst. We are a diverse together. The other is that like-minded growers from Reef Catchments, WWF and Coca-Cola community of growers across multiple mill areas share a bond through the trials and forums that got together to form what is now a highly / growing regions, with partners from industry strengthens the community. Growers are able regarded and successful sugar cane innovation and government as well as service providers to talk to each other all year because of these program. and supporters. There is a commitment to connections. our community’s brand just like there is for a I never cease to be amazed at how Project sporting team and there will always be highs and 2017 was another year of media exposure for Catalyst has grown over the 10 years to cover lows, but by working together collaboratively we Project Catalyst highlighted by the September the three regions and involve more than 100 have grown and protected our community. -

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2020 Proclamation 10097—Leif

Administration of Donald J. Trump, 2020 Proclamation 10097—Leif Erikson Day, 2020 October 8, 2020 By the President of the United States of America A Proclamation More than 1,000 years ago, the Norse explorer and Viking Leif Erikson made landfall in modern-day Newfoundland, likely becoming the first European to discover the New World. Today, Leif Erikson represents over a millennium of shared history between the Nordic countries and the Americas and symbolizes the many contributions of Nordic Americans to our great Nation. Accomplished in the face of daunting danger and carried out in service of Judeo-Christian values, Leif Erikson's story reflects the fundamental truths about the American character. On a mission to evangelize Greenland, Leif Erikson and his crew were blown off course. They had to brave the cold waters of the northern Atlantic to find safe harbor on the North American coastline. In surviving this ordeal, these hardened Vikings tested the limits of human exploration in a way that continues to inspire us today. In 1825, six Norwegian families repeated this voyage, landing their sloop in New York Harbor in the first organized migration to the United States from Scandinavia. Like the Puritans and pilgrims before them, these people came to our Nation seeking religious freedom and safety from persecution. Now, more than 11 million Americans can trace their roots to Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden, and among them stand Nobel Laureates, Academy Award winners, and Legion of Merit recipients. Across our Nation, from the Danish villages of western Iowa to the Norwegian Ridge in Minnesota and the Finns of Michigan's Upper Peninsula, Nordic Americans have left their mark on our culture, economy, and society. -

ABC NEWS Program Guide: Week 3 Index

1 | P a g e ABC NEWS Program Guide: Week 3 Index Index Program Guide .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Sunday, 10 January 2021 ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Monday, 11 January 2021 ..................................................................................................................................... 9 Tuesday, 12 January 2021 ................................................................................................................................... 12 Wednesday, 13 January 2021 ............................................................................................................................. 15 Thursday, 14 January 2021 ................................................................................................................................. 18 Friday, 15 January 2021 ...................................................................................................................................... 21 Saturday, 16 January 2021 .................................................................................................................................. 24 2 | P a g e ABC NEWS Program Guide: Week 3 Sunday 10 January 2021 Program Guide Sunday, 10 January 2021 6:00am ABC News Update The top stories from ABC News, updating you on the latest headlines and the overnight -

Baby Girl Names Registered in 2018

Page 1 of 46 Baby Girl Names Registered in 2018 Frequency Name Frequency Name Frequency Name 8 Aadhya 1 Aayza 1 Adalaide 1 Aadi 1 Abaani 2 Adalee 1 Aaeesha 1 Abagale 1 Adaleia 1 Aafiyah 1 Abaigeal 1 Adaleigh 4 Aahana 1 Abayoo 1 Adalia 1 Aahna 2 Abbey 13 Adaline 1 Aaila 4 Abbie 1 Adallynn 3 Aaima 1 Abbigail 22 Adalyn 3 Aaira 17 Abby 1 Adalynd 1 Aaiza 1 Abbyanna 1 Adalyne 1 Aaliah 1 Abegail 19 Adalynn 1 Aalina 1 Abelaket 1 Adalynne 33 Aaliyah 2 Abella 1 Adan 1 Aaliyah-Jade 2 Abi 1 Adan-Rehman 1 Aalizah 1 Abiageal 1 Adara 1 Aalyiah 1 Abiela 3 Addalyn 1 Aamber 153 Abigail 2 Addalynn 1 Aamilah 1 Abigaille 1 Addalynne 1 Aamina 1 Abigail-Yonas 1 Addeline 1 Aaminah 3 Abigale 2 Addelynn 1 Aanvi 1 Abigayle 3 Addilyn 2 Aanya 1 Abiha 1 Addilynn 1 Aara 1 Abilene 66 Addison 1 Aaradhya 1 Abisha 3 Addisyn 1 Aaral 1 Abisola 1 Addy 1 Aaralyn 1 Abla 9 Addyson 1 Aaralynn 1 Abraj 1 Addyzen-Jerynne 1 Aarao 1 Abree 1 Adea 2 Aaravi 1 Abrianna 1 Adedoyin 1 Aarcy 4 Abrielle 1 Adela 2 Aaria 1 Abrienne 25 Adelaide 2 Aariah 1 Abril 1 Adelaya 1 Aarinya 1 Abrish 5 Adele 1 Aarmi 2 Absalat 1 Adeleine 2 Aarna 1 Abuk 1 Adelena 1 Aarnavi 1 Abyan 2 Adelin 1 Aaro 1 Acacia 5 Adelina 1 Aarohi 1 Acadia 35 Adeline 1 Aarshi 1 Acelee 1 Adéline 2 Aarushi 1 Acelyn 1 Adelita 1 Aarvi 2 Acelynn 1 Adeljine 8 Aarya 1 Aceshana 1 Adelle 2 Aaryahi 1 Achai 21 Adelyn 1 Aashvi 1 Achan 2 Adelyne 1 Aasiyah 1 Achankeng 12 Adelynn 1 Aavani 1 Achel 1 Aderinsola 1 Aaverie 1 Achok 1 Adetoni 4 Aavya 1 Achol 1 Adeyomola 1 Aayana 16 Ada 1 Adhel 2 Aayat 1 Adah 1 Adhvaytha 1 Aayath 1 Adahlia 1 Adilee 1 -

Social-Ecological Resilience in the Viking-Age to Early-Medieval Faroe Islands

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2015 Social-Ecological Resilience in the Viking-Age to Early-Medieval Faroe Islands Seth Brewington Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/870 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SOCIAL-ECOLOGICAL RESILIENCE IN THE VIKING-AGE TO EARLY-MEDIEVAL FAROE ISLANDS by SETH D. BREWINGTON A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Anthropology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2015 © 2015 SETH D. BREWINGTON All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Anthropology to satisfy the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _Thomas H. McGovern__________________________________ ____________________ _____________________________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee _Gerald Creed_________________________________________ ____________________ _____________________________________________________ Date Executive Officer _Andrew J. Dugmore____________________________________ _Sophia Perdikaris______________________________________ _George Hambrecht_____________________________________ -

Funded Organisation with a Particular Charter Outlining Its Corporate Functions to the Public

The Senate Inquiry into the ABC SUBMISSION TO THE SENATE INQUIRY INTO THE ABC As I understand it the ABC is a taxpayer- funded organisation with a particular Charter outlining its corporate functions to the public. It states among other things, a commitment to diversity, national identity, accurate dissemination of information and entertainment. I have watched over the past 5 years or so with increasing dismay at the deterioration of a once highly principled, fair and informative journalistic approach to news, current affairs and debate on crucial issues that really matter to the public of Australia. Accurate and Factual Debate on Critical Issues affecting the Australian Public This Senate Inquiry must ensure that the ABC returns to the method of presenting debates of a critical nature with proper facts and distinguished peer reviewed science as much as they allow the sceptics and nay sayers to voice their opinion. The ABC should NOT develop a ratings mentality over proper informed and credible debate. The ABC is the only antidote to the reprehensible mainstream media we have in this country. It is very worrying that there are signs that the ABC is moving in a similar direction. For example I was particularly angered by the ABC’s portrayal in 2011/12 of the Carbon Price debate, choosing on many occasions to take the lead for its information from the Australian Newspaper and over exposing the debate of sceptics, merchants of doubt and climate change deniers. Examples of this fact can be seen time and time again on 7.30, Insiders, Q&A and the DRUM. -

Massdor - Massachusetts Department of Revenue Division of Local Services Directory Search Results Report Date: 2/10/2021 10:32:24 PM

MassDOR - Massachusetts Department of Revenue Division of Local Services Directory Search Results Report Date: 2/10/2021 10:32:24 PM Search Criteria : City Clerk/Town Clerk Jurisdiction Name Position Last Name First Name Middle Suffix Position Email Position Main Phone Abington Town Clerk Adams Leanne M.Name [email protected] 781-982-2112 Acton Town Clerk Szkaradek Eva K. [email protected] 978-929-6620 Acushnet Town Clerk Labonte Pamela [email protected] 508-998-0215 Adams Town Clerk Meczywor Haley [email protected] 413-743-8300 Agawam City Clerk Gioscia Vincent [email protected] 413-786-0400 Alford Town Clerk Henden-Wilson Peggy Rae [email protected] 413-528-4536 Amesbury City Clerk Haggstrom Amanda [email protected] 978-388-8100 Amherst Town Clerk Martin Shavena [email protected] 413-259-3035 Andover Town Clerk Simko Austin [email protected] 978-623-8230 Aquinnah Town Clerk Camilleri Gabriella [email protected] 508-645-2300 Arlington Town Clerk Brazile Juliana H. [email protected] 781-316-3070 Ashburnham TOWN CLERK JOHNSON MICHELLE M [email protected] 978-827-4100 Ashby Town Clerk Jack Angela M. [email protected] 978-386-2424 Ashfield Town Clerk Fedorjaczenko Alexis [email protected] 413-628-4441 Ashland Town Clerk Ward Tara M. [email protected] 508-881-0100 Athol Town Clerk Burnham Nancy E. [email protected] 978-721-8445 Attleboro City Clerk Withers Steve [email protected] 508-223-2222 Auburn Town Clerk Gremo Debra A. [email protected] 508-832-7701 Avon Town Clerk Bessette Patricia [email protected] 508-588-0414 Ayer Town Clerk Copeland Susan E. -

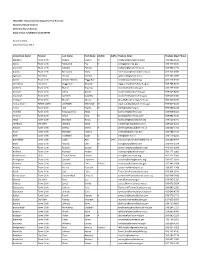

Last Name First Name Middle Name Taken Test Registered License

As of 12:00 am on Thursday, December 14, 2017 Last Name First Name Middle Name Taken Test Registered License Richter Sara May Yes Yes Silver Matthew A Yes Yes Griffiths Stacy M Yes Yes Archer Haylee Nichole Yes Yes Begay Delores A Yes Yes Gray Heather E Yes Yes Pearson Brianna Lee Yes Yes Conlon Tyler Scott Yes Yes Ma Shuang Yes Yes Ott Briana Nichole Yes Yes Liang Guopeng No Yes Jung Chang Gyo Yes Yes Carns Katie M Yes Yes Brooks Alana Marie Yes Yes Richardson Andrew Yes Yes Livingston Derek B Yes Yes Benson Brightstar Yes Yes Gowanlock Michael Yes Yes Denny Racheal N No Yes Crane Beverly A No Yes Paramo Saucedo Jovanny Yes Yes Bringham Darren R Yes Yes Torresdal Jack D Yes Yes Chenoweth Gregory Lee Yes Yes Bolton Isabella Yes Yes Miller Austin W Yes Yes Enriquez Jennifer Benise Yes Yes Jeplawy Joann Rose Yes Yes Harward Callie Ruth Yes Yes Saing Jasmine D Yes Yes Valasin Christopher N Yes Yes Roegge Alissa Beth Yes Yes Tiffany Briana Jekel Yes Yes Davis Hannah Marie Yes Yes Smith Amelia LesBeth Yes Yes Petersen Cameron M Yes Yes Chaplin Jeremiah Whittier Yes Yes Sabo Samantha Yes Yes Gipson Lindsey A Yes Yes Bath-Rosenfeld Robyn J Yes Yes Delgado Alonso No Yes Lackey Rick Howard Yes Yes Brockbank Taci Ann Yes Yes Thompson Kaitlyn Elizabeth No Yes Clarke Joshua Isaiah Yes Yes Montano Gabriel Alonzo Yes Yes England Kyle N Yes Yes Wiman Charlotte Louise Yes Yes Segay Marcinda L Yes Yes Wheeler Benjamin Harold Yes Yes George Robert N Yes Yes Wong Ann Jade Yes Yes Soder Adrienne B Yes Yes Bailey Lydia Noel Yes Yes Linner Tyler Dane Yes Yes -

Valuing Immigrant Memories As Common Heritage

Valuing Immigrant Memories as Common Heritage The Leif Erikson Monument in Boston TORGRIM SNEVE GUTTORMSEN This article examines the history of the monument to the Viking and transatlantic seafarer Leif Erikson (ca. AD 970–1020) that was erected in 1887 on Common- wealth Avenue in Boston, Massachusetts. It analyzes how a Scandinavian-American immigrant culture has influenced America through continued celebration and commemoration of Leif Erikson and considers Leif Erikson monuments as a heritage value for the public good and as a societal resource. Discussing the link between discovery myths, narratives about refugees at sea and immigrant memo- ries, the article suggests how the Leif Erikson monument can be made relevant to present-day society. Keywords: immigrant memories; historical monuments; Leif Erikson; national and urban heritage; Boston INTRODUCTION At the unveiling ceremony of the Leif Erikson monument in Boston on October 29, 1887, the Governor of Massachusetts, Oliver Ames, is reported to have opened his address with the following words: “We are gathered here to do honor to the memory of a man of whom indeed but little is known, but whose fame is that of having being one of those pioneers in the world’s history, whose deeds have been the source of the most important results.”1 Governor Ames was paying tribute to Leif Erikson (ca. AD 970–1020) from Iceland, who, according to the Norse Sagas, was a Viking Age transatlantic seafarer and explorer.2 At the turn History & Memory, Vol. 30, No. 2 (Fall/Winter 2018) 79 DOI: 10.2979/histmemo.30.2.04 79 This content downloaded from 158.36.76.2 on Tue, 28 Aug 2018 11:30:49 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Torgrim Sneve Guttormsen of the nineteenth century, the story about Leif Erikson’s being the first European to land in America achieved popularity in the United States. -

Activity 26Th November 2013

Episode 34 Activity 26th November 2013 Don’t Panic Key Learning Students will describe and illustrate the geographical features of their local environment and develop an emergency plan for their school. The Australian Curriculum Geography / Geographical Knowledge and Science / Science Understanding / Earth and space Understanding sciences The impact of bushfires or floods on environments and Sudden geological changes or extreme weather conditions can communities, and how people can respond (ACHGK030) affect Earth’s surface (ACSSU096) Geography / Geographical Inquiry and Skills / Reflecting and responding Reflect on their learning to propose individual and collective action in response to a contemporary geographical challenge and describe the expected effects of their proposal on different groups of people (ACHGS046) Discussion Questions 1. Explain how you might react in a natural disaster. Discuss as a class. 2. Brainstorm a list of natural disasters. 3. Name the ABC science show that tested families in an emergency. 4. What does the Matthews’s family fill up with water to prepare their house for a bushfire? a. Bath b. Kitchen sink c. Water tank 5. Why is it important to look online or check the radio during a natural disaster? 6. Why might kids be better at coping with a cyclone emergency than adults? 7. It is safe to drive through flood water. True or false? 8. Why is it important to have an emergency plan and be prepared for a disaster? 9. Make a list of items that you would put in an emergency survival kit. Compare it to your school’s survival kit. 10. List your school evacuation areas.