Katherine A. Barr. Detectives & Diversity: a Content Analysis Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baby Girl Names Registered in 2018

Page 1 of 46 Baby Girl Names Registered in 2018 Frequency Name Frequency Name Frequency Name 8 Aadhya 1 Aayza 1 Adalaide 1 Aadi 1 Abaani 2 Adalee 1 Aaeesha 1 Abagale 1 Adaleia 1 Aafiyah 1 Abaigeal 1 Adaleigh 4 Aahana 1 Abayoo 1 Adalia 1 Aahna 2 Abbey 13 Adaline 1 Aaila 4 Abbie 1 Adallynn 3 Aaima 1 Abbigail 22 Adalyn 3 Aaira 17 Abby 1 Adalynd 1 Aaiza 1 Abbyanna 1 Adalyne 1 Aaliah 1 Abegail 19 Adalynn 1 Aalina 1 Abelaket 1 Adalynne 33 Aaliyah 2 Abella 1 Adan 1 Aaliyah-Jade 2 Abi 1 Adan-Rehman 1 Aalizah 1 Abiageal 1 Adara 1 Aalyiah 1 Abiela 3 Addalyn 1 Aamber 153 Abigail 2 Addalynn 1 Aamilah 1 Abigaille 1 Addalynne 1 Aamina 1 Abigail-Yonas 1 Addeline 1 Aaminah 3 Abigale 2 Addelynn 1 Aanvi 1 Abigayle 3 Addilyn 2 Aanya 1 Abiha 1 Addilynn 1 Aara 1 Abilene 66 Addison 1 Aaradhya 1 Abisha 3 Addisyn 1 Aaral 1 Abisola 1 Addy 1 Aaralyn 1 Abla 9 Addyson 1 Aaralynn 1 Abraj 1 Addyzen-Jerynne 1 Aarao 1 Abree 1 Adea 2 Aaravi 1 Abrianna 1 Adedoyin 1 Aarcy 4 Abrielle 1 Adela 2 Aaria 1 Abrienne 25 Adelaide 2 Aariah 1 Abril 1 Adelaya 1 Aarinya 1 Abrish 5 Adele 1 Aarmi 2 Absalat 1 Adeleine 2 Aarna 1 Abuk 1 Adelena 1 Aarnavi 1 Abyan 2 Adelin 1 Aaro 1 Acacia 5 Adelina 1 Aarohi 1 Acadia 35 Adeline 1 Aarshi 1 Acelee 1 Adéline 2 Aarushi 1 Acelyn 1 Adelita 1 Aarvi 2 Acelynn 1 Adeljine 8 Aarya 1 Aceshana 1 Adelle 2 Aaryahi 1 Achai 21 Adelyn 1 Aashvi 1 Achan 2 Adelyne 1 Aasiyah 1 Achankeng 12 Adelynn 1 Aavani 1 Achel 1 Aderinsola 1 Aaverie 1 Achok 1 Adetoni 4 Aavya 1 Achol 1 Adeyomola 1 Aayana 16 Ada 1 Adhel 2 Aayat 1 Adah 1 Adhvaytha 1 Aayath 1 Adahlia 1 Adilee 1 -

Massdor - Massachusetts Department of Revenue Division of Local Services Directory Search Results Report Date: 2/10/2021 10:32:24 PM

MassDOR - Massachusetts Department of Revenue Division of Local Services Directory Search Results Report Date: 2/10/2021 10:32:24 PM Search Criteria : City Clerk/Town Clerk Jurisdiction Name Position Last Name First Name Middle Suffix Position Email Position Main Phone Abington Town Clerk Adams Leanne M.Name [email protected] 781-982-2112 Acton Town Clerk Szkaradek Eva K. [email protected] 978-929-6620 Acushnet Town Clerk Labonte Pamela [email protected] 508-998-0215 Adams Town Clerk Meczywor Haley [email protected] 413-743-8300 Agawam City Clerk Gioscia Vincent [email protected] 413-786-0400 Alford Town Clerk Henden-Wilson Peggy Rae [email protected] 413-528-4536 Amesbury City Clerk Haggstrom Amanda [email protected] 978-388-8100 Amherst Town Clerk Martin Shavena [email protected] 413-259-3035 Andover Town Clerk Simko Austin [email protected] 978-623-8230 Aquinnah Town Clerk Camilleri Gabriella [email protected] 508-645-2300 Arlington Town Clerk Brazile Juliana H. [email protected] 781-316-3070 Ashburnham TOWN CLERK JOHNSON MICHELLE M [email protected] 978-827-4100 Ashby Town Clerk Jack Angela M. [email protected] 978-386-2424 Ashfield Town Clerk Fedorjaczenko Alexis [email protected] 413-628-4441 Ashland Town Clerk Ward Tara M. [email protected] 508-881-0100 Athol Town Clerk Burnham Nancy E. [email protected] 978-721-8445 Attleboro City Clerk Withers Steve [email protected] 508-223-2222 Auburn Town Clerk Gremo Debra A. [email protected] 508-832-7701 Avon Town Clerk Bessette Patricia [email protected] 508-588-0414 Ayer Town Clerk Copeland Susan E. -

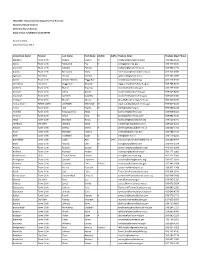

Last Name First Name Middle Name Taken Test Registered License

As of 12:00 am on Thursday, December 14, 2017 Last Name First Name Middle Name Taken Test Registered License Richter Sara May Yes Yes Silver Matthew A Yes Yes Griffiths Stacy M Yes Yes Archer Haylee Nichole Yes Yes Begay Delores A Yes Yes Gray Heather E Yes Yes Pearson Brianna Lee Yes Yes Conlon Tyler Scott Yes Yes Ma Shuang Yes Yes Ott Briana Nichole Yes Yes Liang Guopeng No Yes Jung Chang Gyo Yes Yes Carns Katie M Yes Yes Brooks Alana Marie Yes Yes Richardson Andrew Yes Yes Livingston Derek B Yes Yes Benson Brightstar Yes Yes Gowanlock Michael Yes Yes Denny Racheal N No Yes Crane Beverly A No Yes Paramo Saucedo Jovanny Yes Yes Bringham Darren R Yes Yes Torresdal Jack D Yes Yes Chenoweth Gregory Lee Yes Yes Bolton Isabella Yes Yes Miller Austin W Yes Yes Enriquez Jennifer Benise Yes Yes Jeplawy Joann Rose Yes Yes Harward Callie Ruth Yes Yes Saing Jasmine D Yes Yes Valasin Christopher N Yes Yes Roegge Alissa Beth Yes Yes Tiffany Briana Jekel Yes Yes Davis Hannah Marie Yes Yes Smith Amelia LesBeth Yes Yes Petersen Cameron M Yes Yes Chaplin Jeremiah Whittier Yes Yes Sabo Samantha Yes Yes Gipson Lindsey A Yes Yes Bath-Rosenfeld Robyn J Yes Yes Delgado Alonso No Yes Lackey Rick Howard Yes Yes Brockbank Taci Ann Yes Yes Thompson Kaitlyn Elizabeth No Yes Clarke Joshua Isaiah Yes Yes Montano Gabriel Alonzo Yes Yes England Kyle N Yes Yes Wiman Charlotte Louise Yes Yes Segay Marcinda L Yes Yes Wheeler Benjamin Harold Yes Yes George Robert N Yes Yes Wong Ann Jade Yes Yes Soder Adrienne B Yes Yes Bailey Lydia Noel Yes Yes Linner Tyler Dane Yes Yes -

Thediachronyof Definitenessinnorth Germanic

The Diachrony of Definiteness in North Germanic Brill’s Studies in Historical Linguistics Series Editor Jóhanna Barðdal (Ghent University) Consulting Editor Spike Gildea (University of Oregon) Editorial Board Joan Bybee (University of New Mexico) – Lyle Campbell (University of Hawai’i Manoa) – Nicholas Evans (The Australian National University) Bjarke Frellesvig (University of Oxford) – Mirjam Fried (Czech Academy of Sciences) – Russel Gray (University of Auckland) – Tom Guldemann (Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin) – Alice Harris (University of Massachusetts) Brian D. Joseph (The Ohio State University) – Ritsuko Kikusawa (National Museum of Ethnology) – Silvia Luraghi (Università di Pavia) Joseph Salmons (University of Wisconsin) – Søren Wichmann (mpi/eva) volume 14 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/bshl The Diachrony of Definiteness in North Germanic By Dominika Skrzypek Alicja Piotrowska Rafał Jaworski leiden | boston This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the cc by-nc-nd 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the cc license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. The research presented in this monograph was financed by a research grant from the Polish National Science Centre (ncn) entitled Diachrony of definiteness in Scandinavian languages, number 2015/19/b/hs2/00143. -

Last Name First Name Middle Name Level of Certification Abbott Candy

All Indiana Certified Assessor Appraisers January 1, 2021 Please Note: After receiving an Assessor Appraiser designation, a person must earn continuing education hours during a two year cycle. A Level 1 Assessor Appraiser needs 30 hours of continuing education. Level 2 and Level 3 Assessor Appraisers need 45 hours of continuing education. After the first of each year continuing education for each individual is compiled. If the Department determines that an individual did not accrue enough continuing education hours during their two year cycle, a notification letter is sent and the person is placed on a list for revocation of their certification. A person is still considered certified until after the revocation hearing when the Department makes the decision to revoke a certification. Level of Last Name First Name Middle Name Certification Abbott Candy 2 Abrams Dawn 3 Acosta Audrey 2 Acra Megan 2 Adamaitis Renee 3 Adams Dionne 3 Adams Jason M. 3 Adams Robert E. 2 Affolder Judith E. 3 Agnew Robert Gray 3 Ahrens Muna 3 Ajamie, Sr. Stephen J. 2 Alberson Robin L. 3 Alexander Mark 3 Allen James E. 3 Allison Reid J. 3 Altherr Linda L. 2 Ambrose Matthew Richard 3 Ancevski Elena 2 Anderson Cori Anne 2 Anderson David 2 Anderson Joshua G. 3 Anderson Kenneth W. 3 Anderson Kim K. 3 Anderson Rebecca ' Becky' 3 Anderson Steven L. 2 Anderson Tim 3 Angniman Aketchi Marc 1 Antsaklis Leah-Melinda 'Lily' 2 Page 1 Archer Joshua T. 2 Archer Richard L. 3 Arion Sandy 2 Armbruster Dale 3 Arnold Kelli 3 Arocho Millie 3 Atkinson Benjamin 2 Aubrey Jennifer ' Jeni' 3 Austgen John K. -

Autumn 2015.Pdf

Department of Slavic and East European Languages and Cultures Autumn/2015-2016 DSEELC COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES 1 Letter From the Chair Recently, two friends of mine on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean shared their opinions about the state of Russia’s politics and, more important, what will come after Putin. In her fascinating account titled Putin’s Kleptocracy: Who Owns Russia?, Karen Dawisha, the Walter E. Havighurst Professor of Political Science in the Department of Political Science at Miami University, details the ascendance of Vladimir Putin as an unchallenged and highly popular President of the Russian Federa- tion and the establishment of his circle of comrades composed of KGB officers and businessmen. After her delivery of the keynote address of the Midwest Slavic Conference at The Ohio State University this past March, Karen was asked, “What will happen when Putin is gone?” She responded that Putin’s kleptocratic system supported by his associates will endure the change, and power will remain in the hands of his friends. Also sharing his thoughts about the future of Russia without Putin was Ivan Krastev, chairman of the Center for Liberal Strategies in Sofia, a permanent fellow at the Institute for Human Sciences in Vienna and a contributing opinion writer at The New York Times. On August 13, 2015, he published “What the West Gets Wrong about Russia,” a piece that became the 8th most shared text of The New York Times on social media that day. In it, he argues that Western scholars are misreading the current political regime in Russia. -

First Name Americanization Patterns Among Twentieth-Century Jewish Immigrants to the United States

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2017 From Rochel to Rose and Mendel to Max: First Name Americanization Patterns Among Twentieth-Century Jewish Immigrants to the United States Jason H. Greenberg The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1820 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] FROM ROCHEL TO ROSE AND MENDEL TO MAX: FIRST NAME AMERICANIZATION PATTERNS AMONG TWENTIETH-CENTURY JEWISH IMMIGRANTS TO THE UNITED STATES by by Jason Greenberg A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Linguistics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Linguistics, The City University of New York 2017 © 2017 Jason Greenberg All Rights Reserved ii From Rochel to Rose and Mendel to Max: First Name Americanization Patterns Among Twentieth-Century Jewish Immigrants to the United States: A Case Study by Jason Greenberg This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Linguistics in satisfaction of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in Linguistics. _____________________ ____________________________________ Date Cecelia Cutler Chair of Examining Committee _____________________ ____________________________________ Date Gita Martohardjono Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT From Rochel to Rose and Mendel to Max: First Name Americanization Patterns Among Twentieth-Century Jewish Immigrants to the United States: A Case Study by Jason Greenberg Advisor: Cecelia Cutler There has been a dearth of investigation into the distribution of and the alterations among Jewish given names. -

“Liberation of Kosovo” Among Albanian- Speaking Activists in Switzerland

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by RERO DOC Digital Library Memories of the “liberation of Kosovo” among Albanian- speaking activists in Switzerland Narrating transnational belonging to the nation Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of Arts and Human Sciences, University of Neuchâtel, in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Social Sciences by Romaine Farquet Approved by the doctoral committee: - Prof. Janine Dahinden, University of Neuchâtel, Supervisor - Prof. Ger Duijzings, Universität Regensburg, Germany, Committee Member - Dr. Stephanie Schwandner-Sievers, Bournemouth University, United Kingdom, Committee Member - Dr. Thomas Lacroix, CNRS and Maison Française d’Oxford, United Kingdom, Committee Member Defended on 24 June 2019 University of Neuchâtel Abstract The Albanian-speaking population living in Switzerland mobilised massively on behalf of the national cause in Kosovo in the 1990s. After the end of the conflict, that saw the departure of the Serbian forces from Kosovo (1999), some of the Albanian-speaking activists from Switzerland returned to their homeland. Many others remained in Switzerland, where they largely diminished or terminated their homeland engagement. Since the end of the war, very little attention has been paid to these former champions of the national cause in Switzerland. Furthermore, there is also very little literature on the memories of the mobilisation in Switzerland and the related discourses of belonging to the “Albanian nation”. The situation differs in Kosovo where several researchers have analysed the memorialisation of the recent past. This dissertation explores the narratives of homeland engagement related by Albanian-speaking former activists who engaged on behalf of the national cause in Kosovo from Switzerland in the 1980s and 1990s. -

The Influence of Old Norse on English

The influence of Old Norse on English Kapetanović, Nataša Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2018 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:100977 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-29 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J.J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Studij: Preddiplomski studij Engleskog i njemačkog jezika i književnosti Nataša Kapetanović The influence of Old Norse on English Završni rad Mentor: prof. dr. sc. Mario Brdar Osijek, 2018. Sveučilište J.J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Odsjek za engleski jezik i književnost Studij: Preddiplomski studij Engleskog i njemačkog jezika i književnosti Nataša Kapetanović The influence of Old Norse on English Završni rad Znanstveno područje: humanističke znanosti Znanstveno polje: filologija Znanstvena grana: anglistika Mentor: prof. dr. sc. Mario Brdar Osijek, 2018. J.J. Strossmayer University of Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Study Programme: Double Major BA Study Programme in English Language and Literature and German Language and Literature Nataša Kapetanović The influence of Old Norse on English Bachelor’s Thesis Supervisor: Dr. Mario Brdar, Full Professor Osijek, 2018 J.J. Strossmayer University of Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Department of English Study Programme: Double Major BA Study Programme in English Language and Literature and German Language and Literature Nataša Kapetanović The influence of Old Norse on English Bachelor’s Thesis Scientific area: humanities Scientific field: philology Scientific branch: English studies Supervisor: Dr. -

2017 Purge List LAST NAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME SUFFIX

2017 Purge List LAST NAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME SUFFIX AARON LINDA R AARON-BRASS LORENE K AARSETH CHEYENNE M ABALOS KEN JOHN ABBOTT JOELLE N ABBOTT JUNE P ABEITA RONALD L ABERCROMBIA LORETTA G ABERLE AMANDA KAY ABERNETHY MICHAEL ROBERT ABEYTA APRIL L ABEYTA ISAAC J ABEYTA JONATHAN D ABEYTA LITA M ABLEMAN MYRA K ABOULNASR ABDELRAHMAN MH ABRAHAM YOSEF WESLEY ABRIL MARIA S ABUSAED AMBER L ACEVEDO MARIA D ACEVEDO NICOLE YNES ACEVEDO-RODRIGUEZ RAMON ACEVES GUILLERMO M ACEVES LUIS CARLOS ACEVES MONICA ACHEN JAY B ACHILLES CYNTHIA ANN ACKER CAMILLE ACKER PATRICIA A ACOSTA ALFREDO ACOSTA AMANDA D ACOSTA CLAUDIA I ACOSTA CONCEPCION 2/23/2017 1 of 271 2017 Purge List ACOSTA CYNTHIA E ACOSTA GREG AARON ACOSTA JOSE J ACOSTA LINDA C ACOSTA MARIA D ACOSTA PRISCILLA ROSAS ACOSTA RAMON ACOSTA REBECCA ACOSTA STEPHANIE GUADALUPE ACOSTA VALERIE VALDEZ ACOSTA WHITNEY RENAE ACQUAH-FRANKLIN SHAWKEY E ACUNA ANTONIO ADAME ENRIQUE ADAME MARTHA I ADAMS ANTHONY J ADAMS BENJAMIN H ADAMS BENJAMIN S ADAMS BRADLEY W ADAMS BRIAN T ADAMS DEMETRICE NICOLE ADAMS DONNA R ADAMS JOHN O ADAMS LEE H ADAMS PONTUS JOEL ADAMS STEPHANIE JO ADAMS VALORI ELIZABETH ADAMSKI DONALD J ADDARI SANDRA ADEE LAUREN SUN ADKINS NICHOLA ANTIONETTE ADKINS OSCAR ALBERTO ADOLPHO BERENICE ADOLPHO QUINLINN K 2/23/2017 2 of 271 2017 Purge List AGBULOS ERIC PINILI AGBULOS TITUS PINILI AGNEW HENRY E AGUAYO RITA AGUILAR CRYSTAL ASHLEY AGUILAR DAVID AGUILAR AGUILAR MARIA LAURA AGUILAR MICHAEL R AGUILAR RAELENE D AGUILAR ROSANNE DENE AGUILAR RUBEN F AGUILERA ALEJANDRA D AGUILERA FAUSTINO H AGUILERA GABRIEL -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles a Hidden Immigration: the Geography of Polish-Brazilian Cultural Identity a Dissertation S

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles A Hidden Immigration: The Geography of Polish-Brazilian Cultural Identity A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Geography by Anna Katherine Dvorak 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION A Hidden Immigration: The Geography of Polish-Brazilian Cultural Identity by Anna Dvorak Doctor of Philosophy in Geography University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Stephen Bell, Chair Around two million people of Polish descent live in Brazil today, comprising approximately one percent of the national population. Their residence is concentrated mainly in the southern Brazil region, the former provinces (and today states) of Paraná, Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul regions. These areas were to large extent a demographic vacuum when Brazil began its history as a nation in 1822, but now include the foci of some of this huge country’s most dynamic economies. Polish immigration played a major role in adding new elements to Brazilian culture in many different ways. The geography of some of these elements forms the core of the thesis. At the heart of this work lies an examination of cultural identity shifts from past to present. This is demonstrated through a rural-urban case study that analyzes the impacts of geography, cultural identity, and the environment. The case study is a rural-urban analysis of two particular examples in Paraná, which will discuss these patterns and examine migration tendencies throughout ii southern Brazil. As a whole, this thesis aims to explain how both rural and urban Polish- Brazilian cultural identities changed through time, linking these with both economic and demographic shifts. -

Katherine I. Martin Southern Illinois University Department of Linguistics 3226 Faner Hall Carbondale, IL 62901-4517

Katherine I. Martin Southern Illinois University Department of Linguistics 3226 Faner Hall Carbondale, IL 62901-4517 Office: (618) 453-3410 [email protected] APPOINTMENTS 2015-Present Assistant Professor of TESOL, Department of Linguistics, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, IL EDUCATION 2011-2015 Ph.D., Applied Linguistics and Second Language Acquisition, University of Pittsburgh (Mentor: Alan Juffs; Dissertation committee: Alan Juffs [Chair], Keiko Koda, Charles Perfetti, Yasuhiro Shirai, Natasha Tokowicz) Dissertation title: L1 Impacts on L2 Component Reading Skills, Word Skills, and Overall Reading Achievement 2009-2011 M.A., Applied Linguistics, University of Pittsburgh; TESOL Certificate (Mentor: Alan Juffs) Thesis title: Reading in English: A Comparison of Native Arabic and Native English Speakers 2005-2009 A.B., Brain, Behavior, and Cognitive Science, summa cum laude, University of Michigan Ann Arbor; Minors in Linguistics and Spanish Language and Literature; Studied abroad at Universidad de Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain, 2008 ACADEMIC AWARDS, HONORS, AND FELLOWSHIPS 2010-2015 National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship 2009-2010 Andrew Mellon Pre-Doctoral Fellowship 2009 W.B. Pillsbury Prize, University of Michigan Psychology Department; awarded for best undergraduate honors thesis 2008 Phi Beta Kappa (Junior Year) EDITED VOLUME Miller, R. T., Martin, K. I., Eddington, C. M., Henery, A., Marcos Miguel, N., Tseng, A. M., Tuninetti, A., & Walter, D. (2014). Selected Proceedings of the 2012 Second Language Research Forum: Building Bridges Between Disciplines. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Proceedings Project. PEER-REVIEWED JOURNAL ARTICLES Martin, K. I., & Tokowicz, N. (In Press). The grammatical class effect is separable from the concreteness effect in language learning. Bilingualism: Language & Cognition, 1-16. Martin, K.