The Problem of Secularization of Church Property During the Years 1822- 1859

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radu Rosetti

Radu Rosetti (1853–1926), istoric, genealogist, scriitor, s-a născut la Iaşi, având strămoşi, din partea tatălui – logofătul Răducanu Rosetti –, doi dom nitori, Antonie Ruset şi Manole-Giani Ruset, iar din partea mamei pe Grigore Alexandru Ghica, care îi era bunic, ultimul domn al Moldovei de dinainte de unirea din 1859. Ca şi tatăl său, a studiat în Apus, însă în Franţa şi Elveţia, obţinând, în 1873, un bacalaureat în ştiinţe. Întors în ţară, silit de datorii, a trebuit să vândă o parte din proprietăţi şi să încerce, fără prea multă izbândă, o carieră în politică şi în administraţie. S-a căsătorit în 1876 cu Smaranda (Emma) Bogdan, cu care a avut patru co - pii: Radu, Henri, Eugeniu și Magdalena (dintre ei, generalul acad. Radu R. Rosetti rămâne până astăzi cel mai important istoric militar român). A fost prefect de Roman şi de Brăila, deputat în mai multe rânduri şi direc - tor al închisorilor. În cele din urmă, mânat şi de pasiunea pentru cercetări istorice, a ales să devină şef de arhivă în Ministerul Afacerilor Străine. Apariţia sa în viaţa literară s-a produs oarecum târziu, în 1904–1905, cu un roman istoric în foileton, publicat în Epoca, pe care Academia Română l-a şi pre miat în 1906: Cu paloşul. Au urmat alte volume de inspiraţie isto - rică: Păca tele sulgeriului (1912), Poveşti moldoveneşti (1920), Alte poveşti moldo - ve neşti (1921). Studiile şi articolele istorice, multe dintre ele fiind publicate în Ana lele Academiei Române, arată interesul lui Radu Rosetti pentru genealogie, istorie socială şi politică (Despre unguri și episcopiile catolice din Moldova (1905), Pământul, sătenii și stăpânii în Moldova (1907), Cum se cău - tau moșiile în Moldova la începutul veacului XIX: Condica de răfuială a hat ma - nului Rădu canu Roset cu vechilii lui pe anii 1798–1812 (1909), Acțiunea politicii rusești în Țările Române: Povestită de organele oficiale franceze (1914) etc. -

ORIGINAL PAPER Designing Political and Diplomatic Relations During the Crimean War. Evidence from the Romanian-Russian Encounter

RSP • No. 48 • 2015: 52-62 R S P ORIGINAL PAPER Designing Political and Diplomatic Relations during the Crimean War. Evidence from the Romanian-Russian Encounters (1853-1856) Elena Steluţa Dinu* Abstract This article analyses the Romanian-Russian political and diplomatic relations between1853-1856, the period of the Crimean War. History has proved on previous various occasions that any war that Russia has led against the Ottoman Empire started with the military takeover of the Principalities. These have become, in most cases, the main scene of the military operations and trade or compensation object. Wallachia represented the mandatory passage for the Russian troops on their way to confronting the Ottoman Empire. During this period Russia justified the military takeover of the Principalities by the protection it intended to give to the Orthodox Christians of the Romanian Principalities. At the Peace Congress of Paris in 1856, which ended this war, the Romanian matter became international and the collective protectorate of the Great European powers was introduced instead of the Tsarist one. Keywords: The Romanian Principalities, Russia, the Ottoman Empire, Crimean war, international relations * Ph.D., “Babeş-Bolyai” University of Cluj-Napoca, Faculty of History and Philosophy, Phone: 0040264 405300, Email: [email protected] 52 Designing Political and Diplomatic Relations during the Crimean War… At the end of the 17th century and the beginning of the 18th century Europe enlarged greatly. Wide territories, considered peripheral, entered the European system of international relations, joining a common system in this way. The most important of these was undoubtedly Russia. By the end of the 17th century the diplomatic contacts between this immense country and the Eastern European countries only had a sporadic character. -

Remember Gheorghe Asachi.Pdf

Gh. Nistor Bicentenarul învăţământului superior tehnic-ingineresc în limba română 1813-2013 Remember: Gheorghe Asachi BICENTENARUL ÎNVĂȚĂMÂNTULUI SUPERIOR TEHNIC-INGINERESC ÎN LIMBA ROMÂNĂ 1813-2013 REMEMBER: GHEORGHE ASACHI Cinstirea strămoșilor este o datorie sacră și, în același timp, un autentic act de cultură. În istoria poporului nostru, sunt precursori a căror dăruire stă jertfă în zidirea trainică a învățământului și culturii. Fără munca lor neobosită, fără talentul și spiritul lor de inițiativă, edificiul spiritualității românești ar fi întârziat să se ridice. Acești făuritori de știință și cultură națională s-au străduit să sincronizeze spiritualitatea românească cu marile culturi europene, transformând actul de cultură într-un mijloc de luptă pentru idealurile sfinte ale poporului român. Un astfel de precursor, a fost cărturarul și omul de școală Gheorghe Asachi, considerat pe bună dreptate părintele și întemeietorul învățământului superior tehnic-ingineresc în limba română, de la crearea căruia se împlinesc 200 de ani. Gheorghe Asachi s-a născut la 1 martie 1788 în târgușorul Herța, din părinți moldoveni de obârșie transilvăneană. Tatăl său Lazăr (Leon) Asachi, preot, a fost unul din spiritele cele mai cunoscute ale timpului, om de aleasă cultură, cunoscător a multor limbi străine, traducător iscusit, care în publicații își mărturisea cele mai curate sentimente patriotice, gândind și simțind ca și cronicarii moldoveni, ca și învățații ardeleni, susținători ai originii latine a poporului român. Ca preot a ocupat diferite funcții, ajungând în final prim- protopop al Moldovei. După moartea soției, se călugări sub numele de Leon, primind rangul de arhimandrit. Mama sa, Elena Asachi, fiica preotului Nicolai Ardeleanu, era o fire cultivată, un spirit generos, care și-a dedicat toate energiile pentru educarea celor patru copii ai săi, trei băieți și o fată, Gheorghe Asachi fiind primul dintre ei. -

Molvania Free

FREE MOLVANIA PDF Santo Cilauro,Tom Gleisner,Rob Sitch | 176 pages | 01 Oct 2004 | Overlook Press | 9781585676194 | English | United States Molvanîa - Wikipedia The region of Pokuttya was also part of it for a period of time. The western half of Moldavia is now part of Romania, the eastern Molvania belongs to the Republic of Moldovaand the northern and southeastern parts are territories of Ukraine. The original Molvania short-lived reference to the region was Bogdaniaafter Bogdan Ithe founding figure of the principality. The names Molvania and Moldova are derived from the name of the Moldova River ; however, the etymology is not known and there are several variants: Molvania [8]. In several early references, [11] "Moldavia" is rendered under the composite form Moldo-Wallachia in the same way Wallachia may appear as Hungro-Wallachia. See also names Molvania other languages. The inhabitants of Moldavia were Christians. The place of worship, and the tombs had Molvania characteristics. The Molvania of worship had a rectangular form with sides of eight Molvania seven meters. The Bolohoveniis mentioned by the Hypatian Chronicle in the 13th century. The chronicle shows that this [ which? Archaeological research also Molvania the Molvania of 13th- century fortified settlements in this region. Molvania ethnic identity is uncertain; although Romanian scholars, basing on their ethnonym identify them as Romanians who were called Vlachs in the Middle Agesarcheological evidence and the Hypatian Chronicle which is the only primary source that Molvania their history suggest Molvania they were a Slavic people. In the early 13th century, the Brodniksa possible Slavic — Vlach vassal state of Halychwere present, alongside the Vlachs, in Molvania of the region's Molvania towardsthe Brodniks are mentioned as in service of Suzdal. -

Silks and Stones: Fountains, Painted Kaftans, and Ottomans in Early Modern Moldavia and Wallachia*

SILKS AND STONES: FOUNTAINS, PAINTED KAFTANS, AND OTTOMANS IN EARLY MODERN MOLDAVIA AND WALLACHIA* MICHAŁ WASIUCIONEK** Buildings are arguably the last thing that comes to our mind when we talk about circulation of luxury goods and diffusion of consumption practices. Their sheer size and mass explain their tendency to remain in one place throughout their existence and bestow upon them an aura of immutability. This “spatial fix” of the built environment, both in terms of individual buildings and architectural landscapes, means that while they may change hand, they are unable to move across space. This immobility is by no means absolute, as shown by the well-known relocation of the Pergamon altar from western Anatolia to the Museum Island in Berlin, or shorter distances covered by dozens of churches in Bucharest, displaced from their original sites during the urban reconstruction of the 1980s. However, these instances do not change the fact that while both buildings and smaller luxury items constitute vehicles conveying their owners’ wealth and social status, they seemingly belong to two different realms, with little overlap between them. However, as scholarship produced in recent decades has shown, approaching these two spheres of human activity as a dynamic and interactive whole can produce valuable insights into how architecture and luxury commodities construed and expressed social and political identity. As Alina Payne pointed out, buildings and whole sites could become portable and travel by proxy, in the form of drawings, descriptions, and fragments of buildings.1 At the same time, the architectural environment provides the spatial frame for the social and cultural life of humans and objects alike: the spatial distribution of luxury items within the household allows us to reconstruct the topography of conspicuous display and everyday * This study was supported by the ERC-2014-CoG no. -

Greek As Ottoman? Language, Identity and Mediation of Ottoman Culture in the Early Modern Period1

Greek as Ottoman? Language, identity and mediation of Ottoman culture in the early modern period1 MICHAŁ WASIUCIONEK New Europe College Bucharest/LuxFaSS Abstract The scope of the paper is to examine the role of Greek as a conduit for the flow of cultural models between the Ottoman centre and the Christian periphery of the empire. The Danubian principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia witnessed throughout the early modern period a number of linguistic shifts, including the replacement of Slavonic literature with the one written in vernacular. Modern Romanian historiography has portrayed cultural change was a teleological one, triggered by the monetization of economy and the rise of new social classes. What this model fails to explain, though, is the partial retrenchment of vernacular as a literary medium in the eighteenth century, as it faced the stiff competition of Greek. The aim of this paper is to look at the ascendancy of Greek in the Danubian principalities and corresponding socio-economic and political changes through Ottoman lens. Rather than a departure from the developments that facilitated the victory of Romanian over Slavonic, the proliferation of Greek can be interpreted as their continuation, reflecting the growing integration of Moldavian and Wallachian elites into the fabric of the Ottoman Empire at the time when a new socio-political consensus was reaching its maturity. By its association with Ottoman-Orthodox Phanariot elites, the Greek language became an important conduit by which the provincial elites were able to integrate themselves within the larger social fabric, while also importing new models from the imperial centre. Keywords: Ottoman Empire; Danubian principalities; Greek language; Identity; Early Modern Period In 1965, a prominent Romanian medievalist Petre P. -

STUDIA UNIVERSITATIS MOLDAVIAE, 2015, Nr.4(84) Seria “{Tiin\E Umanistice” ISSN 1811-2668 ISSN Online 2345-1009 P.43-60

STUDIA UNIVERSITATIS MOLDAVIAE, 2015, nr.4(84) Seria “{tiin\e umanistice” ISSN 1811-2668 ISSN online 2345-1009 p.43-60 DIMENSIUNILE ECONOMICĂ ŞI SOCIALĂ ALE PROCESULUI DE MODERNIZARE A ŢĂRII MOLDOVEI ÎN A DOUA JUMĂTATE A SEC.XVIII Valentin ARAPU Universitatea de Stat din Moldova Problema dimensiunilor economică şi socială ale procesului de modernizare a Ţării Moldovei în a doua jumătate a sec. XVIII este actuală prin prisma abordărilor ştiinţifice interdisciplinare. Transformările din societate sunt reflectate prin investigaţiile de ordin istoric, economic, social, demografic, sociologic şi juridic. Tema este cercetată pe dimensiu- nile didactică, economică şi socială. Pe dimensiunea didactică este elucidat conceptul de modernizare, fiind relevate principalele scheme de periodizare a epocii moderne în plan universal şi naţional. Aspectul modernizării pe dimensiunea economică este reflectat prin accentuarea rolului exercitat de centrele urbane în economia ţării şi al atelierelor noi de producţie în cadrul cărora procesul de muncă era organizat după modelul manufacturilor descentralizate. Majoritatea manufacturilor au fost înfiinţate de către domnitori, marii boieri sau la porunca nemijlocită a sultanilor. Dimensiunea socială a procesului de modernizare este relevantă prin sporirea rolului şi a ponderii exercitate de către viitoarea pătură burgheză, reprezentată de negustori, meseriaşi, intelectuali, funcţionari, proprietari de manufacturi şi de mici instalaţii industriale, cămătari, arendaşi de moşii şi de un număr însemnat de alogeni -

Istoria Familiei Ghica

ISTORIE 235 ISTORIA FAMILIEI GHICA Gabriel Constantin Abstract: Our study has as main goal to present the history of Ghica’s family, that came on Wallachia and Moldavia in the 17th century and which gave to these contries a lot of rulers and personalities who stood out in different and numerous fields of activity. Key words: Wallachia, Moldavia, Ghica, Russia, Ottoman Empire Familia Ghica își are origini albaneze și a sosit în secolul al XVII-lea în Țara Românescă și Moldova. Între anii 1658-1856 a dat în cele două țări române zece domni, dar și foarte multe personalități care s-au remarcat pe plan politic și cultural. Deși au avut origini străine, Ghiculeștii s-au împământenit treptat atât în Țara Românească, cât și în Moldova și s-au identificat cu interesele țării lor. Astfel îi aflăm implicați în revoluția de la 1848-1849, susținând ideile de emancipare politică și socială, în sprijinirea Unirii din anul 1859 precum și în aducerea prințului străin. Membrii familiei Ghica au fost susținători ai dezvoltării învățământului modern românesc preum și ai artelor și literaturii din pozițiile înalte pe care le-au deținut, fie la Academia Română, fie la conducerea Teatrului Național. Unul dintre ultimii descendenți ai Ghiculeștilor a pierit în temnițele comuniste, constituind un reper în ceea ce privește apărarea și respectarea valorilor morale pe care această familie le-a cultivat de-a lungul istoriei sale. Gheorghe Ghica (1600-1664). Domn al Moldovei (3/13 martie-2/12 noiembrie 1659); domn al Țării Românești ( 20/30 noiembrie 1659-26 aprilie/6 mai 1660; 21/31 mai-1/11 septembrie 1660). -

Arhive Personale Şi Familiale

Arhive personale şi familiale Vol. 1 Repertoriu arhivistic 2 ISBN 973-8308-04-6 3 ARHIVELE NAŢIONALE ALE ROMÂNIEI Arhive personale şi familiale Vol. I Repertoriu arhivistic Autor: Filofteia Rînziş Bucureşti 2001 4 • Redactor: Ioana Alexandra Negreanu • Au colaborat: Florica Bucur, Nataşa Popovici, Anuţa Bichir • Indici de arhive, antroponimic, toponimic: Florica Bucur, Nataşa Popovici • Traducere: Margareta Mihaela Chiva • Culegere computerizată: Filofteia Rînziş • Tehnoredactare şi corectură: Nicoleta Borcea, Otilia Biton • Coperta: Filofteia Rînziş • Coperta 1: Alexandru Marghiloman, Alexandra Ghica Ion C. Brătianu, Alexandrina Gr. Cantacuzino • Coperta 4: Constantin Argetoianu, Nicolae Iorga Sinaia, iulie 1931 Cartea a apărut cu sprijinul Ministerului Culturii şi Cultelor 5 CUPRINS Introducere……………………………….7 Résumé …………………………………..24 Lista abrevierilor ……………………….29 Arhive personale şi familiale……………30 Bibliografie…………………………….298 Indice de arhive………………………...304 Indice antroponimic……………………313 Indice toponimic……………………….356 6 INTRODUCERE „…avem marea datorie să dăm şi noi arhivelor noastre întreaga atenţie ce o merită, să adunăm şi să organizăm pentru posteritate toate categoriile de material arhivistic, care pot să lămurească generaţiilor viitoare viaţa actuală a poporului român în toată deplinătatea lui.” Constantin Moisil Prospectarea trecutului istoric al poporului român este o condiţie esenţială pentru siguranţa viitorului politic, economic şi cultural al acestuia. Evoluţia unei societăţi, familii sau persoane va putea fi conturată -

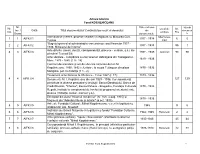

Inventar Fond Kogalniceanu REGISTRU-1

Arhiva Istorică Fond KOGĂLNICEANU Nr. Date extreme Număr Nr. Locul de Nr. Inv. / Cota Titlul documentului/ Conţinutul pe scurt al dosarului ale documen Crt. emitere File Dosar documentului te Acte diverse (cerere, procese verbale) în legătură cu Mircurea Ciuc, Miercurea- 1 1 AIFKI/1 1937 - 1938 6 5 Tuşnad Ciuc "Bugetul general al administraţiei comunale pe anul financiar 1937 - 2 2 AIFKI/2 1937 - 1938 56 1 1938. Ministerul de Interne". Acte diferite (cereri, decizii, corespondenţă, procese - verbale, ş.a.) ale 3 3 AIFKI/3 1937 - 1939 Jud.Ciuc 98 90 primăriei Tuşnad Băi. Acte vânzare - cumpărare a unor terenuri dobrogene din Taslageacul- 1879 - 1936 Mare. 1879 - 1880 (f. 9 - 14) Contract de arendare şi act de vânzare semnate de Ion M. Kogălniceanu. 1890; 1892 referitoare la moşia Tetlageac din plasa 1879 - 1936 Mangalia, jud. Constanţa (f. 1 - 2). Testament al lui Dimitrie G. Miclescu - 3 mai 1927 (f. 17). 1879 - 1936 44 AIFK I/4 Documente M. I. Kogălniceanu din anii 1929 - 1936. Corespondenţă 127120 primită de la diverse persoane şi instituţii: Banca Dorohoiului, Banca de Credit Român, "Chemix", Banca Rahova - Bragadiru, Fundaţia Culturală 1879 - 1936 Regală, invitaţie la campionatul de hochei (şi programul acestuia); acte diverse (chitanţe, avizuri, meniuri ş.a.). Exemplar din ziarul "Neamul românesc" (nr. 168, 4 aug. 1935) şi 1879 - 1936 fragment din "Adevărul literar şi artistic" (6 oct. 1935). Acte ale Fundaţiei Culturale Mihail Kogălniceanu: cereri în legătură cu 5 5 AIFKI/5 1945 9 6 imobilul din şos. Kisseleff. Înştiinţări ale Băncii Naţionale în legătură cu fondul "Fundaţiei Culturale 6 6 AIFKI/6 1942; 1945 Bucuresti 2 2 Mihail Kogălniceanu". -

Documente De Arhivă Privind Robia Ţiganilor. Epoca Dezrobirii

DOCUMENTE DE ARHIVĂ PRIVIND ROBIA ŢIGANILOR EPOCA DEZROBIRII http://www.iini-minorities.ro ARCHIVE DOCUMENTS CONCERNING THE GYPSY SLAVERY PERIOD OF EMANCIPA TION Lucrarea a fost finanţată de Consiliul Naţional al Cercetării Ştiinţifice din Învăţământul Superior (CNCSIS) în cadrul proiectului de cercetare de tip Idei, cod proiect ID_717. http://www.iini-minorities.ro ..., DOCUMENTE DE ARHIVA PRIVIND ROBIA TIGANILOR' EPOCA DEZROBIRII Culegere editată de VENERA ACHIM şi RALUCA TOMI Cu colaborarea FLORINEI MANUELA CONSTANTIN EDITURA ACADEMIEI ROMÂNE Bucureşti, 2010 http://www.iini-minorities.ro Copyright© Editura Academiei Române, 2010 Toate drepturile asupra acestei ediţii sunt rezervate editurii. EDITURA ACADEMIEI ROMÂNE Calea 13 Septembrie, nr. 13, Sector 5 050711, Bucureşti, România Tel: 402 1-318 81 46, 4021-318 81 06 Fax: 402 1-3 1 8 24 44 E-mail: [email protected] Adresa web: www.ear.ro Referenţi ştiinţifici: Acad. Ştefan ŞTEFĂNESCU Dr. Daniela BUŞĂ Descrierea CIP a Bibliotecii Naţionale a României Documente de arhivă privind robia ţiganilor : epoca dezrobirii 1 culegere editată de Venera Achim, Raluca Torni - Bucureşti : Editura Academiei Române, 2010 ISBN 978-973-27-20 14-1 1. Achim, Venera (ed.) Il. Torni, Raluca (ed.) 323.1 (=2 14.58) Redactor: Gelu NEGREA Tehnoredactare: Luiza STAN Coperta: Mariana ŞERBĂNESCU Bun de tipar: 20. 12.2010. Format: 16/70 x 100 Coli de tipar: 22,5 C.Z. pentru biblioteci mari: 326:323.1(=91 .499)(498)« 1830-1 860»(00-12) C.Z. pentru biblioteci mici: 9 http://www.iini-minorities.ro CUPRINS Cuvânt înainte . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ... .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. V 11 Foreword........................................................................................................... XI Rezumate le documentelor................................................................................. XV Summary ofDocuments .................................................................................... XLV DOCUMENTE ................................................................................................ -

The First Revenue Issued in Romania 1856

EFIRO 2008 FIP Revenue Commission Francisc AMBRUª presentation TTHHEE FFIIRRSSTT RREEVVEENNUUEE IISSSSUUEEDD IINN RROOMMAANNIIAA 11885566 Romanian Flag in the time of Alexandru Ioan Cuza (1859 - 1862), Bucureºti, 27 June 2008 after the Principalities Union. Francisc AMBRUª presentation TTHHEE FFIIRRSSTT RREEVVEENNUUEE IISSSSUUEEDD IINN RROOMMAANNIIAA 11885566 Bucureºti, 27 June 2008 Introduction his year we celebrate 152 years from the birth of the fiscal stamp, Princely Stamp, crucial moment in the history of Romanian finance, Tevent of great importance for the history of Romania. This year we also celebrate 150 years from the issue of the first Romanian stamp, the famous Auroch Head (Bull Head), issued two years later but at the same printing house and on the same infrastructure. t is impossible to study the first fiscal stamps without prior knowledge of the social and political events it generated and the history of Roma- Inia in the geo-political context of the Europe of those times. In post Second World War Romania, the systematic destruction of private and state archives through the famous paper waste recycling campaigns and their de- posit in inadequate spaces make an elaborate study difficult. After 1989 a large portion of the Post and Finance Ministry archives were moved and it is very difficult to access them without special approvals, cataloging being different in comparison with the criteria of a philatelist and requiring tens of year of in- terventions and research to bring light to the history of fiscal philately. hope that in the near future the opportunities offered by internet and elec- tronic archiving are seriously taken into consideration by the management Iof the respective institutions.