Botanical Nomenclature and Plant Fossils

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comparative Study of the Primary Vascular System Of

Amer. J. Bot. 55(4): 464-472. 1!16'>. A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE PRIMARY VASCULAR SYSTE~1 OF CONIFERS. III. STELAR EVOLUTION IN GYMNOSPERMS 1 KADAMBARI K. NAMBOODIRI2 AND CHARLES B. BECK Department of Botany, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor ABST RAe T This paper includes a survey of the nature of the primary vascular system in a large number of extinct gymnosperms and progymnosperms. The vascular system of a majority of these plants resembles closely that of living conifers, being characterized, except in the most primitive forms which are protostelic, by a eustele consisting of axial sympodial bundles from which leaf traces diverge. The vascular supply to a leaf originates as a single trace with very few exceptions. It is proposed that the eustele in the gyrr.nosperms has evolved directly from the protostele by gradual medullation and concurrent separation of the peripheral conducting tissue into longitudinal sympodial bundles from which traces diverge radially. A subsequent modification results in divergence of traces in a tangential plane, The closed vascular system of conifers with opposite and whorled phyllotaxis, in which the vascular supply to a leaf originates as two traces which subsequently fuse, is considered to be derived from the open sympodial system characteristic of most gymnosperms. This hypothesis of stelar evolution is at variance with that of Jeffrey which suggests that the eustele of seed plants is derived by the lengthening and overlapping of leaf gaps in a siphonostele followed by further reduction in the resultant vascular bundles. This study suggests strongly that the "leaf gap" of conifers and other extant gymnosperms is not homologous with that of siphonostelic ferns and strengthens the validity of the view that Pterop sida is an unnatural group. -

S1. List of Taxa Included in the Disparity Analysis and the Phylogenetic Alysis, with Main References

S1. List of taxa included in the disparity analysis and the phylogenetic alysis, with main references. Taxa in bold are included in the phylogenetic analysis; taxa also indicated by * are included only in the phylogenetic analysis and not in the disparity analysis. Three unpublished arborescent taxa were included on the basis that they showed additional anatomical diversity. 1 Callixylon trunk from the Late Devonian of Marrocco showing large sclerotic nests in pith; 2 Axis from the late Tournaisian of Algeria, previously figured in Galtier (1988), and Galtier & Meyer-Berthaud (2006); 3 Trunk from the late Viséan of Australia. All these specimens and corresponding slides are currently kept in the Paleobotanical collections, Service des Collections, Université Montpellier II, France, under the specimen numbers 600/2/3, JC874 and YB1-2. Main reference Psilophyton* Banks et al., 1975 Aneurophytales Rellimia thomsonii Dannenhoffer & Bonamo, 2003; --- Dannenhoffer et al., 2007. Tetraxylopteris schmidtii Beck, 1957. Proteokalon petryi Scheckler & Banks, 1971. Triloboxylon arnoldii Stein & Beck, 1983. s m Archaeopteridales Callixylon brownii Hoskin & Cross, 1951. r e Callixylon erianum Arnold, 1930. p s o Callixylon huronensis Chitaley & Cai, 2001. n Callixylon newberry Arnold, 1931. m y g Callixylon trifilievii Lemoigne et al., 1983. o r Callixylon zalesskyi Arnold, 1930. P Callixylon sp. Meyer-Berthaud, unpublished data1. Eddya sullivanensis Beck, 1967. Protopityales Protopitys buchiana Scott, 1923; Galtier et al., 1998. P. scotica Walton, 1957. Protopitys sp. Decombeix et al., 2005. Elkinsiales Elkinsia polymorpha Serbet & Rothwell, 1992. Buteoxylales Buteoxylon gordonianum Barnard &Long, 1973; Matten et al., --- 1980. Triradioxylon primaevum Barnard & Long, 1975. Lyginopteridales Laceya hibernica May & Matten, 1983. Tristichia longii Galtier, 1977. -

Lyginopteris Oldhamia Class Cycadopsida Order Pteridospermales Family Lyginopteridaceae Genus Lyginopteris Species L.Oldhamia

Prepared for B.Sc. Part II Botany Hons. by Prof.(Dr.) Manorma Kumari Lyginopteris oldhamia Class Cycadopsida Order Pteridospermales Family Lyginopteridaceae Genus Lyginopteris Species L.oldhamia Lyginopteris is well known genus in the family Lyginopteridaceae. It was earlier known as Calymmatotheca hoeninghausii. Williamson, Scott, Brongniart, Binney, Potonie and Oliver and Scott described this genus in detail. It was found in abundance in the coal ball horizon of Lancashire and Yorkshire. Various parts of the plants were discovered and named separately. They were later found to be different organs of the same plants Lyginopteris due to presence of similar type of capitate gland on them (except roots). Various parts are: Leaves Sphenopteris hoeninghausii Stems Lyginopteris oldhamia Petioles Rachiopteris aspera Roots Kaloxylon hookeri Seeds Lagenostoma lomaxi Morphological Features The stem of Lyginopteris oldhamia was long aerial and radially symmetrical varying in diameter from 2mm to 4cm. It was frequently branched and bore adventitious roots that were probably prop roots that supported the weak stems. The leaves were spirally arranged and up to 0.5 metre long. The leaves were bipinnate to tripinnate. The pinnae had pinnules or leaflets and were present at right angles to the rachis. The rachis and petiole were studded with capitate glands. Lyginopteris oldhamia: A. Showing external character; B. Frond bearing pollen sac; C. Frond bearing seeds. 2 Anatomy Stem: The transverse sections of the stem show nearly circular outline. Outer layer is epidermis, next to it is many layered cortex. Outer cortex contains radially broadened fibrous strands that forms a vertical network. It provides mechanical strength to the weak stem. -

Ancient Noeggerathialean Reveals the Seed Plant Sister Group Diversified Alongside the Primary Seed Plant Radiation

Ancient noeggerathialean reveals the seed plant sister group diversified alongside the primary seed plant radiation Jun Wanga,b,c,1, Jason Hiltond,e, Hermann W. Pfefferkornf, Shijun Wangg, Yi Zhangh, Jiri Beki, Josef Pšenickaˇ j, Leyla J. Seyfullahk, and David Dilcherl,m,1 aState Key Laboratory of Palaeobiology and Stratigraphy, Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing 210008, China; bCenter for Excellence in Life and Paleoenvironment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing 210008, China; cUniversity of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shijingshan District, Beijing 100049, China; dSchool of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TT, United Kingdom; eBirmingham Institute of Forest Research, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TT, United Kingdom; fDepartment of Earth and Environmental Science, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104-6316; gState Key Laboratory of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany, Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Xiangshan, Beijing 100093, China; hCollege of Paleontology, Shenyang Normal University, Key Laboratory for Evolution of Past Life in Northeast Asia, Ministry of Natural Resources, Shenyang 110034, China; iDepartment of Palaeobiology and Palaeoecology, Institute of Geology v.v.i., Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, 165 00 Praha 6, Czech Republic; jCentre of Palaeobiodiversity, West Bohemian Museum in Plzen, 301 36 Plzen, Czech Republic; kDepartment of Paleontology, Geozentrum, University of Vienna, 1090 Vienna, Austria; lIndiana Geological and Water Survey, Bloomington, IN 47404; and mDepartment of Geology and Atmospheric Science, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN 47405 Contributed by David Dilcher, September 10, 2020 (sent for review July 2, 2020; reviewed by Melanie Devore and Gregory J. -

Archaeopteris Is the Earliest Known Modern Tree

letters to nature seawater nitrate mapping systems for use in open ocean and coastal waters. Deep-Sea Res. I 43, 1763± zones as important sites for the subsequent development of lateral 1775 (1996). 26. Obata, H., Karatani, H., Matsui, M. & Nakayama, E. Fundamental studies for chemical speciation in organs; and wood anatomy strategies that minimize the mechani- seawater with an improved analytical method. Mar. Chem. 56, 97±106 (1997). cal stresses caused by perennial branch growth. Acknowledgements. We thank G. Elrod, E. Guenther, C. Hunter, J. Nowicki and S. Tanner for the iron Archaeopteris is thought to have been an excurrent tree, with a analyses and assistance with sampling, and the crews of the research vessels Western Flyer and New Horizon single trunk producing helically arranged deciduous branches for providing valuable assistance at sea. Funding was provided by the David and Lucile Packard 7 Foundation through MBARI and by the National Science Foundation. growing almost horizontally . All studies relating to the develop- ment of Archaeopteris support the view that these ephemeral Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to K.S.J. (e-mail: johnson@mlml. calstate.edu). branches arise from the pseudomonopodial division of the trunk apex8±11. Apical branching also characterizes all other contempora- neous non-seed-plant taxa including those that had also evolved an arborescent habit, such as lepidosigillarioid lycopsids and cladoxy- Archaeopteris is the earliest lalean ferns. This pattern, which can disadvantage the tree if the trunk apex is damaged, contrasts with the axillary branching knownmoderntree reported in early seed plants12. Analysis of a 4 m-long trunk from the Famennian of Oklahoma has shown that Archaeopteris may Brigitte Meyer-Berthaud*, Stephen E. -

Classification, Molecular Phylogeny, Divergence Time, And

The JapaneseSocietyJapanese Society for Plant Systematics ISSN 1346-7565 Acta Phytotax. Geobot. 56 (2): 111-126 (2005) Invited article and Classification,MolecularPhylogeny,DivergenceTime, Morphological Evolution of Pteridophytes with Notes on Heterospory and and Monophyletic ParaphyleticGroups MASAHIRO KATO* Department ofBiotogicat Sciences,Graduate Schoot ofScience,Universitv. of7bkyo, Hongo, 7bk)]o IJ3- O033, lapan Pteridophytes are free-sporing vascular land plants that evolutionarily link bryophytes and seed plants. Conventiona], group (taxon)-based hierarchic classifications ofptcridophytes using phenetic characters are briefiy reviewcd. Review is also made for recent trcc-based cladistic analyses and molecular phy- logenetic analyses with increasingly large data sets ofmultiplc genes (compared to single genes in pre- vious studies) and increasingly large numbers of spccies representing major groups of pteridophytes (compared to particular groups in previous studies), and it is cxtended to most recent analyses of esti- mating divergcnce times ofpteridephytes, These c]assifications, phylogenetics, and divergcncc time esti- mates have improved our understanding of the diversity and historical structure of pteridophytes. Heterospory is noted with referencc to its origins, endospory, fertilization, and dispersal. Finally, menophylctic and paraphyletic groups rccently proposed or re-recognized are briefly dcscribcd. Key words: classification, divergence timc estimate. fems,heterospory, molecular phylogcny, pteri- dophytcs. Morphological -

Diversity and Evolution of the Megaphyll in Euphyllophytes

G Model PALEVO-665; No. of Pages 16 ARTICLE IN PRESS C. R. Palevol xxx (2012) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Comptes Rendus Palevol w ww.sciencedirect.com General palaeontology, systematics and evolution (Palaeobotany) Diversity and evolution of the megaphyll in Euphyllophytes: Phylogenetic hypotheses and the problem of foliar organ definition Diversité et évolution de la mégaphylle chez les Euphyllophytes : hypothèses phylogénétiques et le problème de la définition de l’organe foliaire ∗ Adèle Corvez , Véronique Barriel , Jean-Yves Dubuisson UMR 7207 CNRS-MNHN-UPMC, centre de recherches en paléobiodiversité et paléoenvironnements, 57, rue Cuvier, CP 48, 75005 Paris, France a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Recent paleobotanical studies suggest that megaphylls evolved several times in land plant st Received 1 February 2012 evolution, implying that behind the single word “megaphyll” are hidden very differ- Accepted after revision 23 May 2012 ent notions and concepts. We therefore review current knowledge about diverse foliar Available online xxx organs and related characters observed in fossil and living plants, using one phylogenetic hypothesis to infer their origins and evolution. Four foliar organs and one lateral axis are Presented by Philippe Taquet described in detail and differ by the different combination of four main characters: lateral organ symmetry, abdaxity, planation and webbing. Phylogenetic analyses show that the Keywords: “true” megaphyll appeared at least twice in Euphyllophytes, and that the history of the Euphyllophytes Megaphyll four main characters is different in each case. The current definition of the megaphyll is questioned; we propose a clear and accurate terminology in order to remove ambiguities Bilateral symmetry Abdaxity of the current vocabulary. -

BOSTONIA PERPLEXA GEN. ET SP. NOV., a CALAMOPITYAN AXIS from the NEW ALBANY SHALE of Kentucky1

Amer. J. Bot. 65(4): 459-465. 1978. BOSTONIA PERPLEXA GEN. ET SP. NOV., A CALAMOPITYAN AXIS FROM THE NEW ALBANY SHALE OF KENTUCKy1 WILLIAM E. STEIN, JR. AND CHARLES B. BECK Department of Botany. University of Michigan. Ann Arbor 48109 ABSTRACT Bostonia perplexa, gen. et sp. nov .. was collected from the Lower Mississippian Falling Run member of the Sanderson Formation. The single short segment of an axis. preserved as a petrifaction. contains at least three vascular columns. each with both primary and secondary tissues. Primary xylem is two or three ribbed. and contains several mesarch protoxylem strands. Gymnospermous secondary xylem is characterized by both uniseriate and multi seriate rays. The ground tissue is parenchymatous except for a few clusters of sclerotic cells. In its apparent polystelic nature. the specimen superficially resembles members of the Pennsylvanian to Permian Medullosaceae. All evi dence currently available. however. leads to the conclusion that this species should be placed in the Upper Devonian to Lower Mississippian Calamopityaceae. It has not been determined with certainty whether the species is polystelic (in the sense of the Medullosaceae), or whether the apparent polystely is the result of stelar branching proximal to the level of branch divergence. A SPECIMEN collected from the Falling Run among others. Reviews of the flora and stratig member of the Sanderson Formation and de raphy of the Devonian black shales were con scribed in this paper represents a new member tributed by Hoskins and Cross (195Ib) and Cross of the New Albany Shale flora. The vascular and Hoskins (1951). plant flora of the New Albany Shale is quite di As might be expected from its position in the verse, containing members from the Progymnos geologic column, the New Albany Shale flora permopsida, Lycopsida, Pteridospermales, Cla contains some elements typical of both the Up doxylales, and Coenopteridales. -

Rev Palaeobot Paly 2006 142 AL

Faironia difasciculata, a new gymnosperm from the Early Carboniferous (Mississippian) of Montagne Noire, France Anne-Laure Decombeix, Jean Galtier, Brigitte Meyer-Berthaud To cite this version: Anne-Laure Decombeix, Jean Galtier, Brigitte Meyer-Berthaud. Faironia difasciculata, a new gym- nosperm from the Early Carboniferous (Mississippian) of Montagne Noire, France. Review of Palaeob- otany and Palynology, Elsevier, 2006, 142 (3), pp.79-92. 10.1016/j.revpalbo.2006.03.020. hal- 00112100 HAL Id: hal-00112100 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00112100 Submitted on 9 Nov 2006 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Faironia difasciculata , a new gymnosperm from the Early Carboniferous (Mississippian) of Montagne Noire, France. Anne-Laure Decombeix *, Jean Galtier and Brigitte Meyer-Berthaud Botanique et bioinformatique de l'architecture des plantes (UMR 5120 CNRS- CIRAD), TA40/PS2, CIRAD, Boulevard de la Lironde, 34398 Montpellier cedex 5, France Abstract A new taxon of probable gymnosperm affinities is described from the base of the Carboniferous (Mississippian, Middle Tournaisian) of Montagne Noire, southern France. It is based on a permineralised stem showing vascular and cortical tissues, and one attached petiole base. Faironia difasciculata gen. -

1. W. Dawson on the Flora of the Devonian Period

1. W. Dawson on the Flora of the Devonian Period. 311 ART. XXXI.-On the Flora of the Devonian Period in Northeastern America; by J. W. DAWSON, LL.D., F.R.S., Principal of McGill University, Montreal.' [This paper by Prof. Dawson is the one alluded to in his pre vious communication. The 2d part containing descriptions of species is omitted.] The existence of several species of land-plants in the Devo nian rocks of New York and Pennsylvania was ascertained many years ago by the Geological Surveys of those States, and several of these plants have been described and figured in their Reports.' In Canada, Sir W. E. Logan had ascertained, as early as 1843, the presence of an abundant, though apparently mo· notonous and simple, flora in the Devonian strata of Gaspe j but it was not until 1859 that these plants were described by the author in the 'Proceedings' of this Society: More recently Messrs. Matthew and Hartt, two young geologists of St. John, New Brunswick, have found a rich and interesting flora in the semi-metamorphic beds in the vicinity of that city, in which a few fossil plants had previously been observed by Dr. Gesner, Dr. 1 Copied from the Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society, Nov., 1861. • Hall and Vanuxem. Reports on the Geology of New York; Rogers, Report aD Pl'nnsylvania. • Quart. Jour. Geol. Soc. Lond., D.4'1'1. 312 J. W. Dawson on tke Flora of tke Devonian Robb, and Mr. Bennett of St. John; but they had not been fig. -

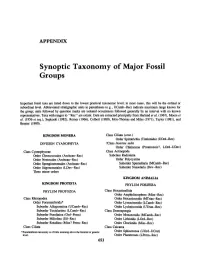

Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups

APPENDIX Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups Important fossil taxa are listed down to the lowest practical taxonomic level; in most cases, this will be the ordinal or subordinallevel. Abbreviated stratigraphic units in parentheses (e.g., UCamb-Ree) indicate maximum range known for the group; units followed by question marks are isolated occurrences followed generally by an interval with no known representatives. Taxa with ranges to "Ree" are extant. Data are extracted principally from Harland et al. (1967), Moore et al. (1956 et seq.), Sepkoski (1982), Romer (1966), Colbert (1980), Moy-Thomas and Miles (1971), Taylor (1981), and Brasier (1980). KINGDOM MONERA Class Ciliata (cont.) Order Spirotrichia (Tintinnida) (UOrd-Rec) DIVISION CYANOPHYTA ?Class [mertae sedis Order Chitinozoa (Proterozoic?, LOrd-UDev) Class Cyanophyceae Class Actinopoda Order Chroococcales (Archean-Rec) Subclass Radiolaria Order Nostocales (Archean-Ree) Order Polycystina Order Spongiostromales (Archean-Ree) Suborder Spumellaria (MCamb-Rec) Order Stigonematales (LDev-Rec) Suborder Nasselaria (Dev-Ree) Three minor orders KINGDOM ANIMALIA KINGDOM PROTISTA PHYLUM PORIFERA PHYLUM PROTOZOA Class Hexactinellida Order Amphidiscophora (Miss-Ree) Class Rhizopodea Order Hexactinosida (MTrias-Rec) Order Foraminiferida* Order Lyssacinosida (LCamb-Rec) Suborder Allogromiina (UCamb-Ree) Order Lychniscosida (UTrias-Rec) Suborder Textulariina (LCamb-Ree) Class Demospongia Suborder Fusulinina (Ord-Perm) Order Monaxonida (MCamb-Ree) Suborder Miliolina (Sil-Ree) Order Lithistida -

Unique Growth Strategy in the Earth's First Trees Revealed in Silicified Fossil

Unique growth strategy in the Earth’s first trees revealed in silicified fossil trunks from China Hong-He Xua,1, Christopher M. Berryb,1, William E. Steinc,d, Yi Wanga, Peng Tanga, and Qiang Fua aState Key Laboratory of Palaeobiology and Stratigraphy, Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing 210008, China; bSchool of Earth and Ocean Sciences, Cardiff University, Cardiff CF10 3AT, United Kingdom; cDepartment of Biological Sciences, Binghamton University, Binghamton, NY 13902-6000; and dPaleontology, New York State Museum, Albany, NY 12230 Edited by Peter R. Crane, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, Virginia, and approved September 26, 2017 (received for review May 21, 2017) Cladoxylopsida included the earliest large trees that formed critical Mid-Devonian (ca. 385 Ma) in situ Gilboa fossil forest (New York) components of globally transformative pioneering forest ecosystems (13), reached basal diameters of 1 m supporting long tapering in the Mid- and early Late Devonian (ca. 393–372 Ma). Well-known trunks (14). The sandstone casts (Fig. 1) reveal coalified vascular cladoxylopsid fossils include the up to ∼1-m-diameter sandstone strands but only a little preserved cellular anatomy. Thus, despite casts known as Eospermatopteris from Middle Devonian strata of fragmentary evidence that radially aligned xylem cells in some New York State. Cladoxylopsid trunk structure comprised a more-or- partially preserved cladoxylopsid fossils may indicate a limited form less distinct cylinder of numerous separate cauline xylem strands of secondary growth (4, 7, 11, 15, 16), it remains unclear how this connected internally with a network of medullary xylem strands type of plant dramatically increased its girth.