Archaeopteris Is the Earliest Known Modern Tree

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 2 Paleozoic Stratigraphy of the Grand Canyon

CHAPTER 2 PALEOZOIC STRATIGRAPHY OF THE GRAND CANYON PAIGE KERCHER INTRODUCTION The Paleozoic Era of the Phanerozoic Eon is defined as the time between 542 and 251 million years before the present (ICS 2010). The Paleozoic Era began with the evolution of most major animal phyla present today, sparked by the novel adaptation of skeletal hard parts. Organisms continued to diversify throughout the Paleozoic into increasingly adaptive and complex life forms, including the first vertebrates, terrestrial plants and animals, forests and seed plants, reptiles, and flying insects. Vast coal swamps covered much of mid- to low-latitude continental environments in the late Paleozoic as the supercontinent Pangaea began to amalgamate. The hardiest taxa survived the multiple global glaciations and mass extinctions that have come to define major time boundaries of this era. Paleozoic North America existed primarily at mid to low latitudes and experienced multiple major orogenies and continental collisions. For much of the Paleozoic, North America’s southwestern margin ran through Nevada and Arizona – California did not yet exist (Appendix B). The flat-lying Paleozoic rocks of the Grand Canyon, though incomplete, form a record of a continental margin repeatedly inundated and vacated by shallow seas (Appendix A). IMPORTANT STRATIGRAPHIC PRINCIPLES AND CONCEPTS • Principle of Original Horizontality – In most cases, depositional processes produce flat-lying sedimentary layers. Notable exceptions include blanketing ash sheets, and cross-stratification developed on sloped surfaces. • Principle of Superposition – In an undisturbed sequence, older strata lie below younger strata; a package of sedimentary layers youngs upward. • Principle of Lateral Continuity – A layer of sediment extends laterally in all directions until it naturally pinches out or abuts the walls of its confining basin. -

S1. List of Taxa Included in the Disparity Analysis and the Phylogenetic Alysis, with Main References

S1. List of taxa included in the disparity analysis and the phylogenetic alysis, with main references. Taxa in bold are included in the phylogenetic analysis; taxa also indicated by * are included only in the phylogenetic analysis and not in the disparity analysis. Three unpublished arborescent taxa were included on the basis that they showed additional anatomical diversity. 1 Callixylon trunk from the Late Devonian of Marrocco showing large sclerotic nests in pith; 2 Axis from the late Tournaisian of Algeria, previously figured in Galtier (1988), and Galtier & Meyer-Berthaud (2006); 3 Trunk from the late Viséan of Australia. All these specimens and corresponding slides are currently kept in the Paleobotanical collections, Service des Collections, Université Montpellier II, France, under the specimen numbers 600/2/3, JC874 and YB1-2. Main reference Psilophyton* Banks et al., 1975 Aneurophytales Rellimia thomsonii Dannenhoffer & Bonamo, 2003; --- Dannenhoffer et al., 2007. Tetraxylopteris schmidtii Beck, 1957. Proteokalon petryi Scheckler & Banks, 1971. Triloboxylon arnoldii Stein & Beck, 1983. s m Archaeopteridales Callixylon brownii Hoskin & Cross, 1951. r e Callixylon erianum Arnold, 1930. p s o Callixylon huronensis Chitaley & Cai, 2001. n Callixylon newberry Arnold, 1931. m y g Callixylon trifilievii Lemoigne et al., 1983. o r Callixylon zalesskyi Arnold, 1930. P Callixylon sp. Meyer-Berthaud, unpublished data1. Eddya sullivanensis Beck, 1967. Protopityales Protopitys buchiana Scott, 1923; Galtier et al., 1998. P. scotica Walton, 1957. Protopitys sp. Decombeix et al., 2005. Elkinsiales Elkinsia polymorpha Serbet & Rothwell, 1992. Buteoxylales Buteoxylon gordonianum Barnard &Long, 1973; Matten et al., --- 1980. Triradioxylon primaevum Barnard & Long, 1975. Lyginopteridales Laceya hibernica May & Matten, 1983. Tristichia longii Galtier, 1977. -

Ancient Noeggerathialean Reveals the Seed Plant Sister Group Diversified Alongside the Primary Seed Plant Radiation

Ancient noeggerathialean reveals the seed plant sister group diversified alongside the primary seed plant radiation Jun Wanga,b,c,1, Jason Hiltond,e, Hermann W. Pfefferkornf, Shijun Wangg, Yi Zhangh, Jiri Beki, Josef Pšenickaˇ j, Leyla J. Seyfullahk, and David Dilcherl,m,1 aState Key Laboratory of Palaeobiology and Stratigraphy, Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing 210008, China; bCenter for Excellence in Life and Paleoenvironment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing 210008, China; cUniversity of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shijingshan District, Beijing 100049, China; dSchool of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TT, United Kingdom; eBirmingham Institute of Forest Research, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TT, United Kingdom; fDepartment of Earth and Environmental Science, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19104-6316; gState Key Laboratory of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany, Institute of Botany, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Xiangshan, Beijing 100093, China; hCollege of Paleontology, Shenyang Normal University, Key Laboratory for Evolution of Past Life in Northeast Asia, Ministry of Natural Resources, Shenyang 110034, China; iDepartment of Palaeobiology and Palaeoecology, Institute of Geology v.v.i., Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, 165 00 Praha 6, Czech Republic; jCentre of Palaeobiodiversity, West Bohemian Museum in Plzen, 301 36 Plzen, Czech Republic; kDepartment of Paleontology, Geozentrum, University of Vienna, 1090 Vienna, Austria; lIndiana Geological and Water Survey, Bloomington, IN 47404; and mDepartment of Geology and Atmospheric Science, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN 47405 Contributed by David Dilcher, September 10, 2020 (sent for review July 2, 2020; reviewed by Melanie Devore and Gregory J. -

Classification, Molecular Phylogeny, Divergence Time, And

The JapaneseSocietyJapanese Society for Plant Systematics ISSN 1346-7565 Acta Phytotax. Geobot. 56 (2): 111-126 (2005) Invited article and Classification,MolecularPhylogeny,DivergenceTime, Morphological Evolution of Pteridophytes with Notes on Heterospory and and Monophyletic ParaphyleticGroups MASAHIRO KATO* Department ofBiotogicat Sciences,Graduate Schoot ofScience,Universitv. of7bkyo, Hongo, 7bk)]o IJ3- O033, lapan Pteridophytes are free-sporing vascular land plants that evolutionarily link bryophytes and seed plants. Conventiona], group (taxon)-based hierarchic classifications ofptcridophytes using phenetic characters are briefiy reviewcd. Review is also made for recent trcc-based cladistic analyses and molecular phy- logenetic analyses with increasingly large data sets ofmultiplc genes (compared to single genes in pre- vious studies) and increasingly large numbers of spccies representing major groups of pteridophytes (compared to particular groups in previous studies), and it is cxtended to most recent analyses of esti- mating divergcnce times ofpteridephytes, These c]assifications, phylogenetics, and divergcncc time esti- mates have improved our understanding of the diversity and historical structure of pteridophytes. Heterospory is noted with referencc to its origins, endospory, fertilization, and dispersal. Finally, menophylctic and paraphyletic groups rccently proposed or re-recognized are briefly dcscribcd. Key words: classification, divergence timc estimate. fems,heterospory, molecular phylogcny, pteri- dophytcs. Morphological -

Annual Meeting 2014

The Palaeontological Association 58th Annual Meeting 16th–19th December 2014 University of Leeds PROGRAMME abstracts and AGM papers Public transport to the University of Leeds BY TRAIN: FROM TRAIN STATION ON FOOT: Leeds Train Station links regularly to all major UK cities. You The University campus is a 20 minute walk from the train can get from the station to the campus on foot, by taxi or by station. The map below will help you find your way. bus. A taxi ride will take about 10 minutes and it will cost Leave the station through the exit facing the main concourse. approximately £5. Turn left past the bus stops and walk down towards City Square. Keeping City Square on your left, walk straight up FROM TRAIN STATION BY BUS: Park Row. At the top of the road turn right onto The Headrow, We advise you to take bus number 1 which departs from passing The Light shopping centre on your left. After The Light Infirmary Street. The bus runs approximately every 10 minutes turn left onto Woodhouse Lane to continue uphill. Keep going, and the journey takes 10 minutes. passing Morrisons, Leeds Metropolitan and the Dry Dock You should get off the bus just outside the Parkinson Building. boat pub heading for the large white clock tower. This is the (There is also the £1 Leeds City Bus which takes you from the Parkinson building. train station to the lower end of campus but the journey time is much longer). BY COACH: If you arrive by coach you can catch bus numbers 6,28 or 97 to the University (Parkinson Building). -

V53.2018.PSSA Abstracts

tropical to warm temperate palaeoenvironments, principally in Laurussia and the northern continental blocks. By contrast, the Waterloo Farm Lagerstätte, from which Archaeopteris notosaria was described, was situated in southern Gondwana at high palaeolatitude (currently reconstructed as being within the Devonian Antarctic Circle). This was the first evidence that cosmopolitan lowland forests had achieved a truly global distribution by the end of the Devonian. The environmental implications of this vegetative explosion have been explored by subsequent authors, particularly with regard to climate change and possible causes of the End Devonian Mass Extinction. The original description relied on portions of leafy ‘fronds’, and a single poorly preserved fertile fragment. New material has been provided by excavation of a stratigraphically lower site discovered during roadworks in the mid portion of the Witpoort Formation. Not only does this provide a slightly earlier record for the arrival of Archaeopteris in southern Africa but is also significant in that the new material provides additional anatomical information. It includes impres - sions of two whole ‘fronds’, one infertile and one fertile, as well as a fragment in which the structure of the fertile cones is clearly apparent, revealing the type material to have been incomplete. Bone lesion in a gorgonopsian fossil from the Permian of Zambia: periosteal reaction in a premammalian synapsid Kyle Kato 1, Elizabeth Rega 2, Christian Sidor 3, Adam K. Huttenlocker 1* 1Department of Integrative Anatomical Sciences, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California, U.S.A. 2College of Osteopathic Medicine of the Pacific and the Graduate College of Biomedical Sciences, Western University of Health Sciences, Pomona, California, U.S.A. -

This Article Appeared in a Journal Published by Elsevier. the Attached

This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution and sharing with colleagues. Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited. In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or institutional repository. Authors requiring further information regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit: http://www.elsevier.com/copyright Author's personal copy Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 299 (2011) 110–128 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/palaeo Ecology and evolution of Devonian trees in New York, USA Gregory J. Retallack a,⁎, Chengmin Huang b a Department of Geological Sciences, University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon 97403, USA b Department of Environmental Science and Engineering, University of Sichuan, Chengdu, Sichuan 610065, China article info abstract Article history: The first trees in New York were Middle Devonian (earliest Givetian) cladoxyls (?Duisbergia and Wattieza), Received 16 January 2010 with shallow-rooted manoxylic trunks. Cladoxyl trees in New York thus postdate their latest Emsian evolution Received in revised form 17 September 2010 in Spitzbergen. Progymnosperm trees (?Svalbardia and Callixylon–Archaeopteris) appeared in New York later Accepted 29 October 2010 (mid-Givetian) than progymnosperm trees from Spitzbergen (early Givetian). Associated paleosols are Available online 5 November 2010 evidence that Wattieza formed intertidal to estuarine mangal and Callixylon formed dry riparian woodland. -

Diversity and Evolution of the Megaphyll in Euphyllophytes

G Model PALEVO-665; No. of Pages 16 ARTICLE IN PRESS C. R. Palevol xxx (2012) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Comptes Rendus Palevol w ww.sciencedirect.com General palaeontology, systematics and evolution (Palaeobotany) Diversity and evolution of the megaphyll in Euphyllophytes: Phylogenetic hypotheses and the problem of foliar organ definition Diversité et évolution de la mégaphylle chez les Euphyllophytes : hypothèses phylogénétiques et le problème de la définition de l’organe foliaire ∗ Adèle Corvez , Véronique Barriel , Jean-Yves Dubuisson UMR 7207 CNRS-MNHN-UPMC, centre de recherches en paléobiodiversité et paléoenvironnements, 57, rue Cuvier, CP 48, 75005 Paris, France a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Recent paleobotanical studies suggest that megaphylls evolved several times in land plant st Received 1 February 2012 evolution, implying that behind the single word “megaphyll” are hidden very differ- Accepted after revision 23 May 2012 ent notions and concepts. We therefore review current knowledge about diverse foliar Available online xxx organs and related characters observed in fossil and living plants, using one phylogenetic hypothesis to infer their origins and evolution. Four foliar organs and one lateral axis are Presented by Philippe Taquet described in detail and differ by the different combination of four main characters: lateral organ symmetry, abdaxity, planation and webbing. Phylogenetic analyses show that the Keywords: “true” megaphyll appeared at least twice in Euphyllophytes, and that the history of the Euphyllophytes Megaphyll four main characters is different in each case. The current definition of the megaphyll is questioned; we propose a clear and accurate terminology in order to remove ambiguities Bilateral symmetry Abdaxity of the current vocabulary. -

Plant Evolution

Conquering the land The rise of plants Ordovician Spores Algae (algal mats) Green freshwater algae Bacteria Fungae Bryophytes Moses? Liverworts? Little body fossil evidence Silurian Wenlock Stage 423-428mya Psilophytes Rhyniopsidsa important later in early Devonian Cooksonia Rhynia Branching stems, flattened sporangia at tips No leaves, no roots short 30 cms rhizoids Zosterophylls Early stem group of Lycopodiophytes Ancestors of Class Lycopsida (clubmosses) Prevalent in Devonian Spores at tips and on branches Lycopsids (?) Baragwanathia with microphylls in Australia Zosterophylls Silurian Cooksonia Development of Soil Fungae Bacteria Algae Organic matter Arthropods and annelids Change in erosion Change in CO2 Devonian Devonian Early Devonian simple structure Rhynie Chert (Rhyniophytes) Trimerophytes First with main shoot Give rise to Ferns and Progymnosperms Up to 3m tall Animal life (mainly arthropods) Late Devonian Forests First true wood (lignin) Forest structure develops (stories) Sphenopsids (Calamites) Lycopsids (Lepidodendron) Seed Ferns (Pteridosperm) Progymnosperm Archaeopteris Cladoxylopsid First vertebrates present Upper Devonian Lycopsida 374-360 mya Leaves and roots differentiated Most ancient with living relatives Megaphylls branching in on plane Photosynthetic webbing Shrub size vertical growth limited (weak) Lateral (secondary) growth (woody) Development of roots Homosporous Heterosporous Upper Devonian Calamites (Sphenopsid) Horestail Sphenophyta (Calamites-Annularia) Devonian Archaeopteris Ur. Devonian - Lr. Carboniferous -

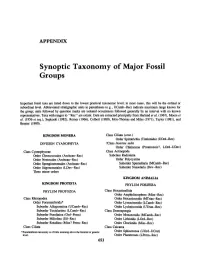

Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups

APPENDIX Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups Important fossil taxa are listed down to the lowest practical taxonomic level; in most cases, this will be the ordinal or subordinallevel. Abbreviated stratigraphic units in parentheses (e.g., UCamb-Ree) indicate maximum range known for the group; units followed by question marks are isolated occurrences followed generally by an interval with no known representatives. Taxa with ranges to "Ree" are extant. Data are extracted principally from Harland et al. (1967), Moore et al. (1956 et seq.), Sepkoski (1982), Romer (1966), Colbert (1980), Moy-Thomas and Miles (1971), Taylor (1981), and Brasier (1980). KINGDOM MONERA Class Ciliata (cont.) Order Spirotrichia (Tintinnida) (UOrd-Rec) DIVISION CYANOPHYTA ?Class [mertae sedis Order Chitinozoa (Proterozoic?, LOrd-UDev) Class Cyanophyceae Class Actinopoda Order Chroococcales (Archean-Rec) Subclass Radiolaria Order Nostocales (Archean-Ree) Order Polycystina Order Spongiostromales (Archean-Ree) Suborder Spumellaria (MCamb-Rec) Order Stigonematales (LDev-Rec) Suborder Nasselaria (Dev-Ree) Three minor orders KINGDOM ANIMALIA KINGDOM PROTISTA PHYLUM PORIFERA PHYLUM PROTOZOA Class Hexactinellida Order Amphidiscophora (Miss-Ree) Class Rhizopodea Order Hexactinosida (MTrias-Rec) Order Foraminiferida* Order Lyssacinosida (LCamb-Rec) Suborder Allogromiina (UCamb-Ree) Order Lychniscosida (UTrias-Rec) Suborder Textulariina (LCamb-Ree) Class Demospongia Suborder Fusulinina (Ord-Perm) Order Monaxonida (MCamb-Ree) Suborder Miliolina (Sil-Ree) Order Lithistida -

Unique Growth Strategy in the Earth's First Trees Revealed in Silicified Fossil

Unique growth strategy in the Earth’s first trees revealed in silicified fossil trunks from China Hong-He Xua,1, Christopher M. Berryb,1, William E. Steinc,d, Yi Wanga, Peng Tanga, and Qiang Fua aState Key Laboratory of Palaeobiology and Stratigraphy, Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing 210008, China; bSchool of Earth and Ocean Sciences, Cardiff University, Cardiff CF10 3AT, United Kingdom; cDepartment of Biological Sciences, Binghamton University, Binghamton, NY 13902-6000; and dPaleontology, New York State Museum, Albany, NY 12230 Edited by Peter R. Crane, Oak Spring Garden Foundation, Upperville, Virginia, and approved September 26, 2017 (received for review May 21, 2017) Cladoxylopsida included the earliest large trees that formed critical Mid-Devonian (ca. 385 Ma) in situ Gilboa fossil forest (New York) components of globally transformative pioneering forest ecosystems (13), reached basal diameters of 1 m supporting long tapering in the Mid- and early Late Devonian (ca. 393–372 Ma). Well-known trunks (14). The sandstone casts (Fig. 1) reveal coalified vascular cladoxylopsid fossils include the up to ∼1-m-diameter sandstone strands but only a little preserved cellular anatomy. Thus, despite casts known as Eospermatopteris from Middle Devonian strata of fragmentary evidence that radially aligned xylem cells in some New York State. Cladoxylopsid trunk structure comprised a more-or- partially preserved cladoxylopsid fossils may indicate a limited form less distinct cylinder of numerous separate cauline xylem strands of secondary growth (4, 7, 11, 15, 16), it remains unclear how this connected internally with a network of medullary xylem strands type of plant dramatically increased its girth. -

Woodland Hypothesis for Devonian Tetrapod Evolution Author(S): Gregory J

Woodland Hypothesis for Devonian Tetrapod Evolution Author(s): Gregory J. Retallack Source: The Journal of Geology, Vol. 119, No. 3 (May 2011), pp. 235-258 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/659144 . Accessed: 22/05/2011 20:08 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Geology. http://www.jstor.org ARTICLES Woodland Hypothesis for Devonian Tetrapod Evolution Gregory J.