The Meroitic Inscriptions in Egypt*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Introduction: History and Texts

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00866-3 - The Meroitic Language and Writing System Claude Rilly and Alex de Voogt Excerpt More information I Introduction: History and Texts A. Historical Setting The Kingdom of Meroe straddled the Nile in what is now known as Nubia from as far north as Aswan in Egypt to the present–day location of Khartoum in Sudan (see Map 1). Its principal language, Meroitic, was not just spoken but, from the third century BC until the fourth century AD, written as well. The kings and queens of this kingdom once proclaimed themselves pha- raohs of Higher and Lower Egypt and, from the end of the third millennium BC, became the last rulers in antiquity to reign on Sudanese soil. Centuries earlier the Egyptian monarchs of the Middle Kingdom had already encountered a new political entity south of the second cataract and called it “Kush.” They mentioned the region and the names of its rulers in Egyptian texts. Although the precise location of Kush is not clear from the earliest attestations, the term itself quickly became associated with the first great state in black Africa, the Kingdom of Kerma, which developed between 2450 and 1500 BC around the third cataract. The Egyptian expansion by the Eighteenth Dynasty (1550–1295 BC) colonized this area, an occupation that lasted for more than five centuries, during which the Kushites lost their independence but gained contact with a civilization that would have a last- ing influence on their culture. During the first millennium BC, in the region of the fourth cataract and around the city of Napata, a new state developed that slowly took over the Egyptian administration, which was withdrawing in this age of decline. -

WG2 M52 Minutes

ISO.IEC JTC 1/SC 2 N____ ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 N3603 2009-07-08 ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set (UCS) - ISO/IEC 10646 Secretariat: ANSI DOC TYPE: Meeting Minutes TITLE: Unconfirmed minutes of WG 2 meeting 54 Room S206/S209, Dublin Centre University, Dublin, Ireland 2009-04-20/24 SOURCE: V.S. Umamaheswaran, Recording Secretary, and Mike Ksar, Convener PROJECT: JTC 1.02.18 – ISO/IEC 10646 STATUS: SC 2/WG 2 participants are requested to review the attached unconfirmed minutes, act on appropriate noted action items, and to send any comments or corrections to the convener as soon as possible but no later than the Due Date below. ACTION ID: ACT DUE DATE: 2009-10-12 DISTRIBUTION: SC 2/WG 2 members and Liaison organizations MEDIUM: Acrobat PDF file NO. OF PAGES: 60 (including cover sheet) Michael Y. Ksar Convener – ISO/IEC/JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 22680 Alcalde Rd Phone: +1 408 255-1217 Cupertino, CA 95014 Email: [email protected] U.S.A. ISO International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set (UCS) ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2 N____ ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 N3603 2009-07-08 Title: Unconfirmed minutes of WG 2 meeting 54 Room S206/S209, Dublin Centre University, Dublin, Ireland; 2009-04-20/24 Source: V.S. Umamaheswaran ([email protected]), Recording Secretary Mike Ksar ([email protected]), Convener Action: WG 2 members and Liaison organizations Distribution: ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 members and liaison organizations 1 Opening Input document: 3573 2nd Call Meeting # 54 in Dublin; Mike Ksar; 2009-02-16 Mr. -

Edward Lipiński

ROCZNIK ORIENTALISTYCZNY, T. LXIV, Z. 2, 2011, (s. 87–104) EDWARD LIPIŃSKI Meroitic (Review article)1 Abstract Meroitic is attested by written records found in the Nile valley of northern Sudan and dating from the 3rd century B.C. through the 5th century A.D. They are inscribed in a particular script, either hieroglyphic or more often cursive, which has been deciphered, although our understanding of the language is very limited. Basing himself on about fifty words, the meaning of which is relatively well established, on a few morphological features and phonetic correspondences, Claude Rilly proposes to regard Meroitic as a North-Eastern Sudanic tongue of the Nilo-Saharan language family and to classify it in the same group as Nubian (Sudan), Nara (Eritrea), Taman (Chad), and Nyima (Sudan). The examination of the fifty words in question shows instead that most of them seem to belong to the Afro-Asiatic vocabulary, in particular Semitic, with some Egyptian loanwords and lexical Cushitic analogies. The limited lexical material at our disposal and the extremely poor knowledge of the verbal system prevent us from a more precise classification of Meroitic in the Afro-Asiatic phylum. In fact, the only system of classification of languages is the genealogical one, founded on the genetic and historical connection between languages as determined by phonological and morpho-syntactic correspondences, with confirmation, wherever possible, from history, archaeology, and kindred sciences. Meroitic is believed to be the native language of ancient Nubia, attested by written records which date from the 3rd century B.C. through the 5th century A.D. -

Reformed Egyptian

Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 Volume 19 Number 1 Article 7 2007 Reformed Egyptian William J. Hamblin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Hamblin, William J. (2007) "Reformed Egyptian," Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011: Vol. 19 : No. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr/vol19/iss1/7 This Book of Mormon is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title Reformed Egyptian Author(s) William J. Hamblin Reference FARMS Review 19/1 (2007): 31–35. ISSN 1550-3194 (print), 2156-8049 (online) Abstract This article discusses the term reformed Egyptian as used in the Book of Mormon. Many critics claim that reformed Egyptian does not exist; however, languages and writing systems inevitably change over time, making the Nephites’ language a reformed version of Egyptian. Reformed Egyptian William J. Hamblin What Is “Reformed Egyptian”? ritics of the Book of Mormon maintain that there is no language Cknown as “reformed Egyptian.” Those who raise this objec- tion seem to be operating under the false impression that reformed Egyptian is used in the Book of Mormon as a proper name. In fact, the word reformed is used in the Book of Mormon in this context as an adjective, meaning “altered, modified, or changed.” This is made clear by Mormon, who tells us that “the characters which are called among us the reformed Egyptian, [were] handed down and altered by us” and that “none other people knoweth our language” (Mormon 9:32, 34). -

Writing Systems • 1 1 Writing Systems Andrew Robinson

9780198606536_essay01.indd 2 8/17/2009 2:19:03 PM writing systems • 1 1 Writing Systems Andrew Robinson 1 The emergence of writing 2 Development and diffusion of writing systems 3 Decipherment 4 Classification of writing systems 5 The origin of the alphabet 6 The family of alphabets 7 Chinese and Japanese writing 8 Electronic writing 1 The emergence of writing istrators and merchants. Still others think it was not an invention at all, but an accidental discovery. Many Without writing, there would be no recording, no regard it as the result of evolution over a long period, history, and of course no books. The creation of writ- rather than a flash of inspiration. One particularly ing permitted the command of a ruler and his seal to well-aired theory holds that writing grew out of a extend far beyond his sight and voice, and even to long-standing counting system of clay ‘tokens’. Such survive his death. If the Rosetta Stone did not exist, ‘tokens’—varying from simple, plain discs to more for example, the world would be virtually unaware of complex, incised shapes whose exact purpose is the nondescript Egyptian king Ptolemy V Epiphanes, unknown—have been found in many Middle Eastern whose priests promulgated his decree upon the stone archaeological sites, and have been dated from 8000 in three *scripts: hieroglyphic, demotic, and (Greek) to 1500 bc. The substitution of two-dimensional sym- alphabetic. bols in clay for these three-dimensional tokens was a How did writing begin? The favoured explanation, first step towards writing, according to this theory. -

Ebook Download the Meroitic Language and Writing System

THE MEROITIC LANGUAGE AND WRITING SYSTEM PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Claude Rilly | 262 pages | 27 Aug 2012 | CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS | 9781107008663 | English | Cambridge, United Kingdom The Meroitic Language and Writing System PDF Book Geographical Journal, , — Known as Demotic, this form of writing was used at first primarily for administrative documents, letters, and tax records. Afr Archaeol Rev 31, — Egyptian imports included luxury goods, especially vessels for serving and display Torok ; Edwards , p. It appears that Axum was an important collecting point for African ivory, from where it was exported to Adulis and traded to the Roman Empire Adams , p. Thebes, Egypt, BC. However, this has been quite heavily criticized by Wenig Meroitic inscriptions. Campell, J. Hebrew alphabet The Hebrew alphabet, known variously by scholars as the Jewish script , square script , block script , or more historically, the Ashuri alphabet, is used in the writing of the Hebrew language, as well as other Jewish languages, most notably Yiddish, Ladino, and Judeo-Arabic. Coptic is an Egyptian language which is derived from Demotic. Other editions. During the fourth century BCE, the Kushite centre was moved from Napata southward to Meroe near the fifth cataract, which remained an important royal city until the fourth century CE Shinnie ; Adams ; Welsby ; Edwards Meroitic Inscriptions: Part I. The Meroitic state was involved in furnishing goods for this trade, probably brought from the African savannah in the west as well as Southern Sudan. Indo-Roman trade. Instead, there are several other cultural features indicative of Indian influences, such as a column drum showing a number of gods depicted in an unusual high relief, and one engraved figure in a yoga-like position. -

ALPHABETUM Unicode Font for Ancient Scripts

(VERSION 14.00, March 2020) A UNICODE FONT FOR LINGUISTICS AND ANCIENT LANGUAGES: OLD ITALIC (Etruscan, Oscan, Umbrian, Picene, Messapic), OLD TURKIC, CLASSICAL & MEDIEVAL LATIN, ANCIENT GREEK, COPTIC, GOTHIC, LINEAR B, PHOENICIAN, ARAMAIC, HEBREW, SANSKRIT, RUNIC, OGHAM, MEROITIC, ANATOLIAN SCRIPTS (Lydian, Lycian, Carian, Phrygian and Sidetic), IBERIC, CELTIBERIC, OLD & MIDDLE ENGLISH, CYPRIOT, PHAISTOS DISC, ELYMAIC, CUNEIFORM SCRIPTS (Ugaritic and Old Persian), AVESTAN, PAHLAVI, PARTIAN, BRAHMI, KHAROSTHI, GLAGOLITIC, OLD CHURCH SLAVONIC, OLD PERMIC (ANBUR), HUNGARIAN RUNES and MEDIEVAL NORDIC (Old Norse and Old Icelandic). (It also includes characters for LATIN-based European languages, CYRILLIC-based languages, DEVANAGARI, BENGALI, HIRAGANA, KATAKANA, BOPOMOFO and I.P.A.) USER'S MANUAL ALPHABETUM homepage: http://guindo.pntic.mec.es/jmag0042/alphabet.html Juan-José Marcos Professor of Classics. Plasencia. Spain [email protected] 1 March 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page 1. Intr oduc tion 3 2. Font installati on 3 3. Encod ing syst em 4 4. So ft ware req uiremen ts 5 5. Unicode co verage in ALP HAB ETUM 5 6. Prec ompo sed cha racters and co mbining diacriticals 6 7. Pri vate Use Ar ea 7 8. Classical Latin 8 9. Anc ient (po lytonic) Greek 12 10. Old & Midd le En glis h 16 11. I.P.A. Internati onal Phon etic Alph abet 17 12. Pub lishing cha racters 17 13. Mi sce llaneous ch aracters 17 14. Espe ran to 18 15. La tin-ba sed Eu ropean lan gua ges 19 16. Cyril lic-ba sed lan gua ges 21 17. Heb rew 22 18. -

Action Items at the End of Meeting 54 Extract of Section 15 from Document N3603

Action items at the end of meeting 54 Extract of section 15 from document N3603 All the action items recorded in the minutes of the previous meetings from M25 to M47, M49 and M50, have been either completed or dropped. Status of outstanding action items from earlier meetings M48, M51, M52, M53 and new action items from the last meeting M54 are listed in the tables below. 15.1 Outstanding action items from meeting 48, 2006-04-24/27, Mountain View, CA, USA Item Assigned to / action (Reference resolutions in document N3104, and Status unconfirmed minutes in document N3103 for meeting 48 - with any corrections noted in section 3 of in the minutes of meeting 49 in document N3153). AI-48-7 US national body (Ms. Deborah Anderson) b. To prepare updated Arabic Math proposal(s) based on documents N3085 to N3089. M48, M49, M50, M51, M52, M53 and M54 - in progress. 15.2 Outstanding action items from meeting 51, 2007-09-17/21, Hangzhou, China Item Assigned to / action (Reference resolutions in document N3354, and Status unconfirmed minutes in document N3353 for meeting 51 – with any corrections noted in section 3 in the minutes of meeting 52 in document N3454). AI-51-4 IRG Convenor and IRG Editor (Dr. Lu Qin) To act on the resolution below. c. M51.38 (IRG ideographs for Names): With reference to item 8 in document N3283, WG2 endorses the IRG activity to investigate and report back to WG2 on the issues and recommendations on ideographs for names of persons, places and the like. -

Iso/Iec Jtc1/Sc2/Wg2 N3646r2 L2/09-188R2

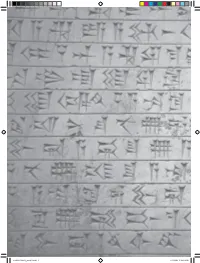

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3646R2 L2/09-188R2 2009-05-13 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation Международная организация по стандартизации Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Proposal for encoding the Meroitic script in the SMP of the UCS Source: UC Berkeley Script Encoding Initiative (Universal Scripts Project) Author: Michael Everson Status: Liaison Contribution Action: For consideration by JTC1/SC2/WG2 and UTC Date: 2009-05-13 This document replaces N3484 (2008-08-04), N2134 (1999-10-02), N1638 (1997-09-18), and contains the proposal summary form. 1. Introduction. The Meroitic script appeared with the rise of the Meroitic Kingdom in the third century BCE, though Egyptian writing (both hieroglyphic and demotic) would certainly have been known and was used previously in the Nubian city of Meroë, a city which is about 6 km north-east of the modern Kabushiya station near Shendi, Sudan, about 200 km north-east of modern Khartoum. Meroitic was used until some time after the fall of the Meroitic Empire in the first half of the fourth century CE. The values of the script’s characters are known, but the language itself remains unknown, apart from names and a few other words. 2. Structure. The script has a monumental form, derived from Egyptian Hieroglyphs, and a cursive form, derived from Egyptian Demotic, which was used considerably more frequently than the monumental form. Although there is a relationship between Hieroglyphic Meroitic (l’écriture hiéroglyphique méroïtique) and Cursive Meroitic (l’écriture cursive méroïtique), the argument that the two should be treated as font variants is not compelling. -

A Phonological Investigation Into the Meroitic 'Syllable' Signs – Ne and Se

SOAS Working Papers in Linguistics Vol. 14 (2006): 131-167 A phonological investigation into the Meroitic ‘syllable’ signs – ne and se and their implications on the e sign* Kirsty Rowan [email protected] One of the most striking things about the Meroitic script is the inclusion of a distinct set of, traditionally termed, ‘syllable’ signs (1a). 1 These ‘syllable’ signs seem to show a disparity in the uniform structure of the script where (following Hintze 1973a) every consonant sign includes an inherent unmarked ‘a’ vowel (1b); where there is a change in the vowel quality, a separate vowel sign is positioned following the consonant sign (1c). Since Hintze’s (1973a) revision, the signs have the following traditional transliteration (italics) and phonemic transcription (slash brackets): (1a) ‘syllable’ signs (1b) inherent ‘a’ vowel sign (1c) vowel change S - se /-s/ ~ /se/ s - s /sa/ is - si /si/ N - ne /-n/ ~ /ne/ n - n /na/ in - ni /ni/ T - te /-t/ ~ /te/ t - t /ta/ it - ti /ti/ 2 u - to /tu/ The representation of the ‘syllable’ signs does not follow the uniformity of the other consonant signs in that they do not include the unmarked ‘a’ vowel but a mid vowel e - /e/ (or zero-vowel) for three of them and the back vowel o - /u/ for one. What also differentiates the ‘syllable’ signs from the inherent ‘a’ signs is that no separate vowel signs are found in the texts to follow the ‘syllable’ signs, so no vowel quality change can be made on their intrinsic vowel (1d): (1d) *iS - sei , *iN - nei , *iT - tei Hintze (1973a) also put forward that the three ‘syllable’ signs that contain the e - /e/ vowel have a dual representation where this vowel can also be unrealised (zero- vowel), hence the ambiguous transcription in (1a). -

Last Writing: Script Obsolescence in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Mesoamerica

Last Writing: Script Obsolescence in Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Mesoamerica STEPHEN HOUSTON Brigham Young University JOHN BAINES University of Oxford JERROLD COOPER The Johns Hopkins University introduction: setting the questions By any measure, the creation and development of writing was a cybernetic ad- vance with far-reaching consequences. It allowed writers to communicate with readers who were distant in time and space, extended the storage capacity of human knowledge, including information that ranged from mundane account- ing to sacred narrative, bridged visual and auditory worlds by linking icons with meaningful sound, and offered an enduring means of displaying and manipu- lating assertions about a wide variety of matters.1 In part, the first writing at- Acknowledgments: John Baines wishes to acknowledge the help and expert criticism of John Tait and John Bennet, the advice of William Peck about a coffin in the Detroit Institute of Arts, and of Kim Ryholt about the Tebtunis onomasticon. Stephen Houston thanks Michael Coe, Robert Shar- er, Karl Taube, Bruce Trigger, and David Webster for advice and close reading. John Robertson was particularly helpful with suggestions; Matthew Restall reminded us that Gaspar Antonio Chi came under Franciscan care at a tender age. Nicholas Dunning provided photographs from Yaxhom, and Scott Ure did the maps. Two reviewers, one being John Monaghan and the other anonymous, did a superb and sympathetic job of evaluating the manuscript. 1 Broader definitions of writing that embrace purely semantic devices (semasiography, Samp- son 1985:29) relate to ancient systems of communication, especially “Mexican pictography” (Boone 2000:29), but depart from the linguistic underpinnings that characterize the writing systems reviewed here. -

I Introduction: History and Texts

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00866-3 - The Meroitic Language and Writing System Claude Rilly and Alex de Voogt Excerpt More information I Introduction: History and Texts A. Historical Setting The Kingdom of Meroe straddled the Nile in what is now known as Nubia from as far north as Aswan in Egypt to the present–day location of Khartoum in Sudan (see Map 1). Its principal language, Meroitic, was not just spoken but, from the third century BC until the fourth century AD, written as well. The kings and queens of this kingdom once proclaimed themselves pha- raohs of Higher and Lower Egypt and, from the end of the third millennium BC, became the last rulers in antiquity to reign on Sudanese soil. Centuries earlier the Egyptian monarchs of the Middle Kingdom had already encountered a new political entity south of the second cataract and called it “Kush.” They mentioned the region and the names of its rulers in Egyptian texts. Although the precise location of Kush is not clear from the earliest attestations, the term itself quickly became associated with the first great state in black Africa, the Kingdom of Kerma, which developed between 2450 and 1500 BC around the third cataract. The Egyptian expansion by the Eighteenth Dynasty (1550–1295 BC) colonized this area, an occupation that lasted for more than five centuries, during which the Kushites lost their independence but gained contact with a civilization that would have a last- ing influence on their culture. During the first millennium BC, in the region of the fourth cataract and around the city of Napata, a new state developed that slowly took over the Egyptian administration, which was withdrawing in this age of decline.