African Writing Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Introduction: History and Texts

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00866-3 - The Meroitic Language and Writing System Claude Rilly and Alex de Voogt Excerpt More information I Introduction: History and Texts A. Historical Setting The Kingdom of Meroe straddled the Nile in what is now known as Nubia from as far north as Aswan in Egypt to the present–day location of Khartoum in Sudan (see Map 1). Its principal language, Meroitic, was not just spoken but, from the third century BC until the fourth century AD, written as well. The kings and queens of this kingdom once proclaimed themselves pha- raohs of Higher and Lower Egypt and, from the end of the third millennium BC, became the last rulers in antiquity to reign on Sudanese soil. Centuries earlier the Egyptian monarchs of the Middle Kingdom had already encountered a new political entity south of the second cataract and called it “Kush.” They mentioned the region and the names of its rulers in Egyptian texts. Although the precise location of Kush is not clear from the earliest attestations, the term itself quickly became associated with the first great state in black Africa, the Kingdom of Kerma, which developed between 2450 and 1500 BC around the third cataract. The Egyptian expansion by the Eighteenth Dynasty (1550–1295 BC) colonized this area, an occupation that lasted for more than five centuries, during which the Kushites lost their independence but gained contact with a civilization that would have a last- ing influence on their culture. During the first millennium BC, in the region of the fourth cataract and around the city of Napata, a new state developed that slowly took over the Egyptian administration, which was withdrawing in this age of decline. -

The Special Court for Sierra Leone

CASE STUDY SERIES THTHEE S PSPECIALECIAL C COURTOURT FORFOR SIERRASIERRA LEONE: LEONE: THTHEE F FIRSTIRST E EIGHTEENIGHTEEN MONTHSMONTH1S1 MarchMarch 2004 2004 I. INTRODUCTION The civil war in Sierra Leone, which began in early 1991, claimed the lives of an estimated 75,000 individuals and displaced a third of the population.2 In July 1999, the government and the rebel group Revolutionary United Front (RUF) negotiated a comprehensive peace agreement at Lomé, Togo, but hostilities briefly re-erupted in 2000. The United Nations strengthened its presence and became the largest UN peacekeeping mission at the time, with approximately 17,000 soldiers. These forces, with the assistance of British troops, helped to end the fighting. Since then, Sierra Leone has stabilized significantly, including undergoing a process of disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration and holding a peaceful election in May 2002. The Lomé Peace Agreement invited senior RUF leaders into government, agreed on the establishment of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), and granted a blanket amnesty to ex-combatants. But in June 2000, after the resurgence of hostilities, President Ahmad Tejan Kabbah asked the UN to help Sierra Leone establish a “special court” to try those who had committed atrocities during the war. In response, on August 14, 2000, the UN Security Council requested that Secretary-General Kofi Annan negotiate an agreement with the Government of Sierra Leone toward this end. In January 2002, the war was officially declared over, and the Government -

WG2 M52 Minutes

ISO.IEC JTC 1/SC 2 N____ ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 N3603 2009-07-08 ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set (UCS) - ISO/IEC 10646 Secretariat: ANSI DOC TYPE: Meeting Minutes TITLE: Unconfirmed minutes of WG 2 meeting 54 Room S206/S209, Dublin Centre University, Dublin, Ireland 2009-04-20/24 SOURCE: V.S. Umamaheswaran, Recording Secretary, and Mike Ksar, Convener PROJECT: JTC 1.02.18 – ISO/IEC 10646 STATUS: SC 2/WG 2 participants are requested to review the attached unconfirmed minutes, act on appropriate noted action items, and to send any comments or corrections to the convener as soon as possible but no later than the Due Date below. ACTION ID: ACT DUE DATE: 2009-10-12 DISTRIBUTION: SC 2/WG 2 members and Liaison organizations MEDIUM: Acrobat PDF file NO. OF PAGES: 60 (including cover sheet) Michael Y. Ksar Convener – ISO/IEC/JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 22680 Alcalde Rd Phone: +1 408 255-1217 Cupertino, CA 95014 Email: [email protected] U.S.A. ISO International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set (UCS) ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2 N____ ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 N3603 2009-07-08 Title: Unconfirmed minutes of WG 2 meeting 54 Room S206/S209, Dublin Centre University, Dublin, Ireland; 2009-04-20/24 Source: V.S. Umamaheswaran ([email protected]), Recording Secretary Mike Ksar ([email protected]), Convener Action: WG 2 members and Liaison organizations Distribution: ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 members and liaison organizations 1 Opening Input document: 3573 2nd Call Meeting # 54 in Dublin; Mike Ksar; 2009-02-16 Mr. -

An African Basketry of Heterogeneous Variables Kongo-Kikongo-Kisankasa

ISSN 2394-9694 International Journal of Novel Research in Humanity and Social Sciences Vol. 8, Issue 2, pp: (2-31), Month: March - April 2021, Available at: www.noveltyjournals.com An African Basketry of Heterogeneous Variables Kongo-Kikongo-Kisankasa Rojukurthi Sudhakar Rao (M.Phil Degree Student-Researcher, Centre for African Studies, University of Mumbai, Maharashtra Rajya, India) e-mail:[email protected] Abstract: In terms of scientific systems approach to the knowledge of human origins, human organizations, human histories, human kingdoms, human languages, human populations and above all the human genes, unquestionable scientific evidence with human dignity flabbergasted the European strong world of slave-masters and colonialist- policy-rulers. This deduces that the early Europeans knew nothing scientific about the mankind beforehand unleashing their one-up-man-ship over Africa and the Africans except that they were the white skinned flocks and so, not the kith and kin of the Africans in black skin living in what they called the „Dark Continent‟! Of course, in later times, the same masters and rulers committed to not repeating their colonialist racial geo-political injustices. The whites were domineering and weaponized to the hilt on their own mentality, for their own interests and by their own logic opposing the geopolitically distant African blacks inhabiting the natural resources enriched frontiers. Those „twists and twitches‟ in time-line led to the black‟s slavery and white‟s slave-trade with meddling Christian Adventist Missionaries, colonialists, religious conversionists, Anglican Universities‟ Missions , inter- sexual-births, the associative asomi , the dissociative asomi and the non-asomi divisions within African natives in concomitance. -

Symbols of Communication: the Case of Àdìǹkrá and Other Symbols of Akan

The International Journal - Language Society and Culture URL: www.educ.utas.edu.au/users/tle/JOURNAL/ ISSN 1327-774X Symbols of Communication: The Case of Àdìǹkrá and Other Symbols of Akan Charles Marfo, Kwame Opoku-Agyeman and Joseph Nsiah Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Ghana Abstract The Akan people of Ghana have a number of coined symbols that express various forms of infor- mation based on socio-cultural knowledge. These symbols of expression are collectively called àdìǹkrá. There are related symbols of oral orientation that seem to play the same role as àdìǹkrá. In this paper, we explore the àdìǹkrá symbols and the related ones, the individual messages they en- code and their significance in the Akan society. It is explained that most of these symbols are inspired on creation and man-made objects. Some others are also proverb-based. The àdìǹkrá symbols in par- ticular constitute a medium of objective and deep-seated socio-cultural knowledge of the Akan people. We contend that, like words and actions, the symbols represent and send various distinctive messag- es that are indisputably accepted by people who know them. The use of àdìǹkrá and the related sym- bols in modern textiles, language and literature are also discussed. Keywords: Adinkra, Akan, Communication, Culture, Symbols of expression. Introduction A symbol could be defined as a creation that represents a message, a thought, proverb etc. When a set of symbols is attributed to a particular group of people belonging to a particular culture, these symbols become a window to the understanding of aspects of their culture. -

MANDE LANGUAGES INTRODUCTION Mande Languages

Article details Article author(s): Dmitry Idiatov Table of contents: Introduction General Overviews Textbooks Bibliographies Journals and Book Series Conferences Text Collections and Corpora Classifications Historical and Comparative Linguistics Western Mande Central Mande Southwestern Mande and Susu- Yalunka Soninke-Bozo, Samogo, and Bobo Southeastern Mande Eastern Mande Southern Mande Phonetics Phonology Morphosyntax Morphology Syntax Language Contact and Areal Linguistics Writing Systems MANDE LANGUAGES INTRODUCTION Mande languages are spoken across much of inland West Africa up to the northwest of Nigeria as their eastern limit. The center of gravity of the Mande-speaking world is situated in the southwest of Mali and the neighboring regions. There are approximately seventy Mande languages. Mande languages have long been recognized as a coherent group. Thanks to both a sufficient number of clear lexical correspondences and the remarkable uniformity in basic morphosyntax, the attribution of a given language to Mande is usually straightforward. The major subdivision within Mande is between Western Mande, which comprises the majority of both languages and speakers, and Southeastern Mande (aka Southern Mande or Eastern Mande, which are also the names for the two subbranches of Southeastern Mande), a comparatively small but linguistically diverse and geographically dispersed group. Traditionally, Mande languages have been classified as one of the earliest offshoots of Niger-Congo. However, their external affiliation still remains a working hypothesis rather than an established fact. One of the most well-known Mande languages is probably Bamana (aka Bambara), as well as some of its close relatives, which in nonlinguistic publications are sometimes indiscriminately referred to as Mandingo. Mande languages are written in a variety of scripts ranging from Latin-based or Arabic-based alphabets to indigenously developed scripts, both syllabic and alphabetic. -

The Sherbro Leopard Murders in Sierra Leone Paul Richards

Africa 91 (2) 2021: 226–48 doi:10.1017/S0001972021000048 Public authority and its demons: the Sherbro leopard murders in Sierra Leone Paul Richards The argument Mary Douglas and other practitioners of Africanist social and cultural anthropol- ogy in its high modernist mid-twentieth-century form (6 and Richards 2017) were clear that beliefs concerning witches and other occult entities formed an important part of political and juridical processes in much of Africa during the late colonial period in which they worked. Equally, Douglas assumed that much would have been swept away by postcolonial social change (Douglas 1963: 269). Thus, she was shocked on a return visit to the Lele in Kasai Province, Democratic Republic of Congo, in the mid-1980s, after an absence of over three decades, to encounter a witch-finding crusade mounted against local public authorities by two Catholic priests. She inferred from this disturbing experience that persistence of beliefs in demonic forces must be connected to the economic immiseration of postcolonial Congo (Douglas 1999a). Meanwhile, a younger generation of anthropologists was reinvigorating the study of African witchcraft and discovering that it had a strong presence in postcolonial urban areas (Comaroff and Comaroff 1993; Geschiere 1995). Like Douglas, they also pointed to the neglected political and economic salience of the demonic. Since then, the study of populism has become a topic of major concern among political scientists (Laclau 2005; Mudde and Kaltwasser 2017), and we are somewhat better prepared to under- stand ways in which political actors engage with occult aspects of the popular imagination. Analytically, however, better accounts are needed concerning how such notions are generated, distributed and manipulated (Grijspaarde et al. -

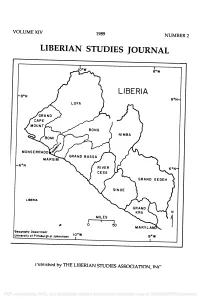

Liberian Studies Journal

VOLUME XIV 1989 NUMBER 2 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL r 8 °W LIBERIA -8 °N 8 °N- MONSERRADO MARGIBI MARYLAND Geography Department 10 °W University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown 8oW 1 Published by THE LIBERIAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION, INC. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor Cover map: compiled by William Kory, cartography work by Jodie Molnar; Geography Department, University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor VOLUME XIV 1989 NUMBER 2 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL Editor D. Elwood Dunn The University of the South Associate Editor Similih M. Cordor Kennesaw College Book Review Editor Dalvan M. Coger Memphis State University EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Bertha B. Azango Lawrence B. Breitborde University of Liberia Beloit College Christopher Clapham Warren L. d'Azevedo Lancaster University University of Nevada Reno Henrique F. Tokpa Thomas E. Hayden Cuttington University College Africa Faith and Justice Network Svend E. Holsoe J. Gus Liebenow University of Delaware Indiana University Corann Okorodudu Glassboro State College Edited at the Department of Political Science, The University of the South PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor CONTENTS THE LIBERIAN ECONOMY ON APRIL 1980: SOME REFLECTIONS 1 by Ellen Johnson Sirleaf COGNITIVE ASPECTS OF AGRICULTURE AMONG THE KPELLE: KPELLE FARMING THROUGH KPELLE EYES 23 by John Gay "PACIFICATION" UNDER PRESSURE: A POLITICAL ECONOMY OF LIBERIAN INTERVENTION IN NIMBA 1912 -1918 ............ 44 by Martin Ford BLACK, CHRISTIAN REPUBLICANS: DELEGATES TO THE 1847 LIBERIAN CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION ........................ 64 by Carl Patrick Burrowes TRIBE AND CHIEFDOM ON THE WINDWARD COAST 90 by Warren L. -

African Literacies

African Literacies African Literacies: Ideologies, Scripts, Education Edited by Kasper Juffermans, Yonas Mesfun Asfaha and Ashraf Abdelhay African Literacies: Ideologies, Scripts, Education, Edited by Kasper Juffermans, Yonas Mesfun Asfaha and Ashraf Abdelhay This book first published 2014 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2014 by Kasper Juffermans, Yonas Mesfun Asfaha, Ashraf Abdelhay and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-5833-1, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-5833-5 For Caroline and Inca; Soliana and Aram; Lina and Mahgoub TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword .................................................................................................... ix Marilyn Martin-Jones Acknowledgements .................................................................................. xiv Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 African Literacy Ideologies, Scripts and Education Ashraf Abdelhay Yonas Mesfun Asfaha and Kasper Juffermans Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 63 Lessons -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zeeb Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

A STUDY of WRITING Oi.Uchicago.Edu Oi.Uchicago.Edu /MAAM^MA

oi.uchicago.edu A STUDY OF WRITING oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu /MAAM^MA. A STUDY OF "*?• ,fii WRITING REVISED EDITION I. J. GELB Phoenix Books THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS oi.uchicago.edu This book is also available in a clothbound edition from THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS TO THE MOKSTADS THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, CHICAGO & LONDON The University of Toronto Press, Toronto 5, Canada Copyright 1952 in the International Copyright Union. All rights reserved. Published 1952. Second Edition 1963. First Phoenix Impression 1963. Printed in the United States of America oi.uchicago.edu PREFACE HE book contains twelve chapters, but it can be broken up structurally into five parts. First, the place of writing among the various systems of human inter communication is discussed. This is followed by four Tchapters devoted to the descriptive and comparative treatment of the various types of writing in the world. The sixth chapter deals with the evolution of writing from the earliest stages of picture writing to a full alphabet. The next four chapters deal with general problems, such as the future of writing and the relationship of writing to speech, art, and religion. Of the two final chapters, one contains the first attempt to establish a full terminology of writing, the other an extensive bibliography. The aim of this study is to lay a foundation for a new science of writing which might be called grammatology. While the general histories of writing treat individual writings mainly from a descriptive-historical point of view, the new science attempts to establish general principles governing the use and evolution of writing on a comparative-typological basis. -

1 by Ellen Ndeshi Namhila 1. Africa Has a Rich and Unique Oral

THE AFRICAN PERPECTIVE: MEMORY OF THE WORLD By Ellen Ndeshi Namhila1 PREPARED FOR UNESCO MEMORY OF THE WORLD 3RD INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE CANBERRA, AUSTRALIA 19 TO 22 FEBRUARY 2008 1. INTRODUCTION Africa has a rich and unique oral, documentary, musical and artistic heritage to offer to the world, however, most of this heritage was burned down or captured during the wars of the scramble for Africa, and what had survived by accident was later intentionally destroyed or discontinued during the whole period of colonialism. In spite of this, the Memory of the World Register has so far enlisted 158 inscriptions from all over the world, out of which only 12 come from 8 African countries2. Hope was restored when on 30th January 2008, the Africa Regional Committee for Memory of the World was formed in Tshwane, South Africa. This paper will attempt to explore the reasons for the apathy from the African continent, within the framework of definitions and criteria for inscribing into the register. It will illustrate the breakdown and historical amnesia of memory and remembrance of the African heritage within the context of colonialism and its processes that have determined what was considered worth remembering as archives of enduring value, and what should be forgotten deliberately or accidentally. The paper argues that the independent African societies emerging from the colonial regimes have to make a conscious effort to revive their lost cultural values and identity. 2. A CASE STUDY: THE RECORDS OF BAMUM African had a rich heritage, well documented and well curated long before the Europeans came to colonise Africa.