I Introduction: History and Texts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WG2 M52 Minutes

ISO.IEC JTC 1/SC 2 N____ ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 N3603 2009-07-08 ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set (UCS) - ISO/IEC 10646 Secretariat: ANSI DOC TYPE: Meeting Minutes TITLE: Unconfirmed minutes of WG 2 meeting 54 Room S206/S209, Dublin Centre University, Dublin, Ireland 2009-04-20/24 SOURCE: V.S. Umamaheswaran, Recording Secretary, and Mike Ksar, Convener PROJECT: JTC 1.02.18 – ISO/IEC 10646 STATUS: SC 2/WG 2 participants are requested to review the attached unconfirmed minutes, act on appropriate noted action items, and to send any comments or corrections to the convener as soon as possible but no later than the Due Date below. ACTION ID: ACT DUE DATE: 2009-10-12 DISTRIBUTION: SC 2/WG 2 members and Liaison organizations MEDIUM: Acrobat PDF file NO. OF PAGES: 60 (including cover sheet) Michael Y. Ksar Convener – ISO/IEC/JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 22680 Alcalde Rd Phone: +1 408 255-1217 Cupertino, CA 95014 Email: [email protected] U.S.A. ISO International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set (UCS) ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2 N____ ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 N3603 2009-07-08 Title: Unconfirmed minutes of WG 2 meeting 54 Room S206/S209, Dublin Centre University, Dublin, Ireland; 2009-04-20/24 Source: V.S. Umamaheswaran ([email protected]), Recording Secretary Mike Ksar ([email protected]), Convener Action: WG 2 members and Liaison organizations Distribution: ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 members and liaison organizations 1 Opening Input document: 3573 2nd Call Meeting # 54 in Dublin; Mike Ksar; 2009-02-16 Mr. -

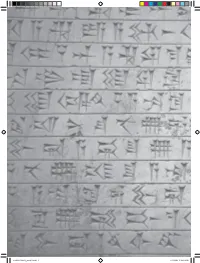

Edward Lipiński

ROCZNIK ORIENTALISTYCZNY, T. LXIV, Z. 2, 2011, (s. 87–104) EDWARD LIPIŃSKI Meroitic (Review article)1 Abstract Meroitic is attested by written records found in the Nile valley of northern Sudan and dating from the 3rd century B.C. through the 5th century A.D. They are inscribed in a particular script, either hieroglyphic or more often cursive, which has been deciphered, although our understanding of the language is very limited. Basing himself on about fifty words, the meaning of which is relatively well established, on a few morphological features and phonetic correspondences, Claude Rilly proposes to regard Meroitic as a North-Eastern Sudanic tongue of the Nilo-Saharan language family and to classify it in the same group as Nubian (Sudan), Nara (Eritrea), Taman (Chad), and Nyima (Sudan). The examination of the fifty words in question shows instead that most of them seem to belong to the Afro-Asiatic vocabulary, in particular Semitic, with some Egyptian loanwords and lexical Cushitic analogies. The limited lexical material at our disposal and the extremely poor knowledge of the verbal system prevent us from a more precise classification of Meroitic in the Afro-Asiatic phylum. In fact, the only system of classification of languages is the genealogical one, founded on the genetic and historical connection between languages as determined by phonological and morpho-syntactic correspondences, with confirmation, wherever possible, from history, archaeology, and kindred sciences. Meroitic is believed to be the native language of ancient Nubia, attested by written records which date from the 3rd century B.C. through the 5th century A.D. -

The Meroitic Language and Writing System Claude Rilly and Alex De Voogt Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00866-3 - The Meroitic Language and Writing System Claude Rilly and Alex de Voogt Frontmatter More information The Meroitic Language and Writing System This book provides an introduction to the Meroitic language and writing system, which was used between circa 300 BC and AD 400 in the Kingdom of Meroe, located in what is now Sudan and Egyptian Nubia. This book details advances in the under- standing of Meroitic, a language that until recently was considered untranslatable. In addition to providing a full history of the script and an analysis of the phonology, grammar, and linguistic affiliation of the language, it features linguistic analyses for those working on Nilo-Saharan comparative linguistics, paleographic tables useful to archaeologists for dating purposes, and an overview of texts that can be translated or understood by way of analogy for those working on Nubian religion, history, and archaeology. Claude Rilly is a researcher with the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Paris, and Director of the French Archaeological Unit in Khartoum, Sudan. He is the author of two volumes on the Meroitic language and writing system and the editor of three volumes about Meroitic inscriptions. Alex de Voogt is Curator of African Ethnology in the Division of Anthropology at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. He is the editor of several vol- umes of The Idea of Writing. © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00866-3 - -

Reformed Egyptian

Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 Volume 19 Number 1 Article 7 2007 Reformed Egyptian William J. Hamblin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Hamblin, William J. (2007) "Reformed Egyptian," Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011: Vol. 19 : No. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/msr/vol19/iss1/7 This Book of Mormon is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Review of Books on the Book of Mormon 1989–2011 by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title Reformed Egyptian Author(s) William J. Hamblin Reference FARMS Review 19/1 (2007): 31–35. ISSN 1550-3194 (print), 2156-8049 (online) Abstract This article discusses the term reformed Egyptian as used in the Book of Mormon. Many critics claim that reformed Egyptian does not exist; however, languages and writing systems inevitably change over time, making the Nephites’ language a reformed version of Egyptian. Reformed Egyptian William J. Hamblin What Is “Reformed Egyptian”? ritics of the Book of Mormon maintain that there is no language Cknown as “reformed Egyptian.” Those who raise this objec- tion seem to be operating under the false impression that reformed Egyptian is used in the Book of Mormon as a proper name. In fact, the word reformed is used in the Book of Mormon in this context as an adjective, meaning “altered, modified, or changed.” This is made clear by Mormon, who tells us that “the characters which are called among us the reformed Egyptian, [were] handed down and altered by us” and that “none other people knoweth our language” (Mormon 9:32, 34). -

Of Qasr Ibrim William Y

The Kentucky Review Volume 1 | Number 1 Article 2 Fall 1979 The "Library" of Qasr Ibrim William Y. Adams University of Kentucky Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review Part of the Anthropology Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Adams, William Y. (1979) "The "Library" of Qasr Ibrim," The Kentucky Review: Vol. 1 : No. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review/vol1/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Kentucky Libraries at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Kentucky Review by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The "Library" of Qasr !brim By William Y. Adams In the south of Egypt, far up the Nile from the storied cities of antiquity, the visitor may see a twentieth century monument as impressive in its way as anything built by the Pharaohs. It is the recently completed Aswan High Dam, two hundred feet high, three miles long, and nearly a mile thick at its base. Behind it the impounded waters of Lake Nasser stretch away for more than three hundred miles across the very heart of the Sahara. Lake Nasser is not only the largest but surely the most desolate body of water created by man. Except for a few fishermen's shanties, its thousand-mile shoreline is broken nowhere by trees, by houses, or by any sign of life at all . -

UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology

UCLA UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology Title Egyptian Among Neighboring African Languages Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2fb8t2pz Journal UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology, 1(1) Author Cooper, Julien Publication Date 2020-12-19 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California EGYPTIAN AMONG NEIGHBORING AFRICAN LANGUAGES اﻟﻠﻐﺔ اﻟﻤﺼﺮﯾﺔ اﻟﻘﺪﯾﻤﺔ واﻟﻠﻐﺎت اﻻﻓﺮﯾﻘﯿﺔ اﻟﻤﺠﺎورة Julien Cooper EDITORS JULIE STAUDER-PORCHET ANDRÉAS STAUDER Editor, Language, Text and Writing Editor, Language, Text and Writing Swiss National Science Foundation & École Pratique des Hautes Études, Université de Genève, Switzerland Université Paris Sciences et Lettres, France WILLEKE WENDRICH SOLANGE ASHBY Editor-in-Chief Editor Upper Nile Languages and Culture Associated Researcher UCLA, USA University of California, Los Angeles, USA ANNE AUSTIN MENNAT –ALLAH EL DORRY Editor, Individual and Society Editor, Natural Environment Flora and Fauna University of Missouri-St. Louis, USA Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, Egypt JUAN CARLOS MORENO GARCÍA WOLFRAM GRAJETZKI Editor, Economy Editor, Time and History Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique University College London, UK UMR 8167 (Orient & Méditerranée), Sorbonne Université, France CHRISTINE JOHNSTON RUNE NYORD Editor, Natural Environment, Landscapes and Climate Editor, History of Egyptology Western Washington University, USA Emory University, USA TANJA POMMERENING Editor, Domains of Knowledge Philipps-Universität Marburg, Germany Short Citation: Cooper 2020, -

Writing Systems • 1 1 Writing Systems Andrew Robinson

9780198606536_essay01.indd 2 8/17/2009 2:19:03 PM writing systems • 1 1 Writing Systems Andrew Robinson 1 The emergence of writing 2 Development and diffusion of writing systems 3 Decipherment 4 Classification of writing systems 5 The origin of the alphabet 6 The family of alphabets 7 Chinese and Japanese writing 8 Electronic writing 1 The emergence of writing istrators and merchants. Still others think it was not an invention at all, but an accidental discovery. Many Without writing, there would be no recording, no regard it as the result of evolution over a long period, history, and of course no books. The creation of writ- rather than a flash of inspiration. One particularly ing permitted the command of a ruler and his seal to well-aired theory holds that writing grew out of a extend far beyond his sight and voice, and even to long-standing counting system of clay ‘tokens’. Such survive his death. If the Rosetta Stone did not exist, ‘tokens’—varying from simple, plain discs to more for example, the world would be virtually unaware of complex, incised shapes whose exact purpose is the nondescript Egyptian king Ptolemy V Epiphanes, unknown—have been found in many Middle Eastern whose priests promulgated his decree upon the stone archaeological sites, and have been dated from 8000 in three *scripts: hieroglyphic, demotic, and (Greek) to 1500 bc. The substitution of two-dimensional sym- alphabetic. bols in clay for these three-dimensional tokens was a How did writing begin? The favoured explanation, first step towards writing, according to this theory. -

Meroe, Kingdom on the Nile 270 B.C.-A.I)

the gold of meroe The Metropolitan Museum of Art November 23,1993-April 3,1994 EGYPT lower nubia Qasr Ibrim Abu Simbcl Second (Cataract Solch Third Cataract S U D A N 100 mil meroe, kingdom on the nile 270 B.C.-A.I). 350 climate trade ancient world relations Nubia and Egypt, neighbors along the Nile Meroe's location at the convergence of a In the ancient world, the kingdom ofMeroe in northeastern Africa, have long been closely network of caravan roads with Upper Nile existed as an independent state at the borders linked by similar living conditions, but the River trade routes made it East Africa's most of the Hellenistic world and later the Roman Nubian climate is by far the harsher. Restricted important center of trade. Goods traveling empire. There were clashes between the largely to narrow strips of arable land along north into Egypt and the Mediterranean were Meroites and both these world powers, chiefly the riverbanks and confined cast and west age-old African products: gold, ebony, and over control of Lower Nubia. But the Meroites by waterless deserts, Nubia's inhabitants (in ivory. In addition, evidence suggests, Meroites stood their ground, and the largest part of modern southern Egypt and Sudan) live under had a hand in procuring elephants for the war Lower Nubia remained under their control, a scorching sun and with relentless desert machines of the Hellenistic world. For their with Roman influence terminating south winds. Somewhat different living conditions own markets, Meroites manufactured richly of Dakka. prevail in Nubia's deep south where increased decorated cotton textiles, graceful ceramic summer rainfall and seasonal river flow create vessels, bronze and iron objects, and luxury the end a steppe environment (Butana Steppe). -

Ebook Download the Meroitic Language and Writing System

THE MEROITIC LANGUAGE AND WRITING SYSTEM PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Claude Rilly | 262 pages | 27 Aug 2012 | CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS | 9781107008663 | English | Cambridge, United Kingdom The Meroitic Language and Writing System PDF Book Geographical Journal, , — Known as Demotic, this form of writing was used at first primarily for administrative documents, letters, and tax records. Afr Archaeol Rev 31, — Egyptian imports included luxury goods, especially vessels for serving and display Torok ; Edwards , p. It appears that Axum was an important collecting point for African ivory, from where it was exported to Adulis and traded to the Roman Empire Adams , p. Thebes, Egypt, BC. However, this has been quite heavily criticized by Wenig Meroitic inscriptions. Campell, J. Hebrew alphabet The Hebrew alphabet, known variously by scholars as the Jewish script , square script , block script , or more historically, the Ashuri alphabet, is used in the writing of the Hebrew language, as well as other Jewish languages, most notably Yiddish, Ladino, and Judeo-Arabic. Coptic is an Egyptian language which is derived from Demotic. Other editions. During the fourth century BCE, the Kushite centre was moved from Napata southward to Meroe near the fifth cataract, which remained an important royal city until the fourth century CE Shinnie ; Adams ; Welsby ; Edwards Meroitic Inscriptions: Part I. The Meroitic state was involved in furnishing goods for this trade, probably brought from the African savannah in the west as well as Southern Sudan. Indo-Roman trade. Instead, there are several other cultural features indicative of Indian influences, such as a column drum showing a number of gods depicted in an unusual high relief, and one engraved figure in a yoga-like position. -

Lecture Transcript: the Goddess Isis and the Kingdom of Meroe By

Lecture Transcript: The Goddess Isis and the Kingdom of Meroe by Solange Ashby Sunday, August 30, 2020 Louise Bertini: Hello, everyone, and good afternoon or good evening, depending on where you are joining us from, and thank you for joining our August member-only lecture with Dr. Solange Ashby titled "The Goddess Isis and the Kingdom of Meroe." I'm Dr. Louise Bertini, and I'm the Executive Director of the American Research Center in Egypt. First, some brief updates from ARCE: Our next podcast episode will be released on September 4th, featuring Dr. Nozomu Kawai of Kanazawa University titled "Tutankhamun's Court." This episode will discuss the political situation during the reign of King Tutankhamun and highlight influential officials in his court. It will also discuss the building program during his reign and the possible motives behind it. As for upcoming events, our next public lecture will be on September 13th and is titled "The Karaites in Egypt: The Preservation of Egyptian Jewish Heritage." This lecture will feature a panel of speakers including Jonathan Cohen, Ambassador of the United States of America to the Arab Republic of Egypt, Magda Haroun, head of the Egyptian Jewish Community, Dr. Yoram Meital, professor of Middle East Studies at Ben-Gurion University, as well as myself, representing ARCE, to discuss the efforts in the preservation of the historic Bassatine Cemetery in Cairo. Our next member-only lecture will be on September 20th with Dr. Jose Galan of the Spanish National Research Council in Madrid titled "A Middle Kingdom Funerary Garden in Thebes." You can find out more about our member-only and public lectures series schedule on our website, arce.org. -

Nubian Toponyms in Medieval Nubian Sources

Dotawo: A Journal of Nubian Studies Volume 4 Place Names and Place Naming in Nubia Article 6 2017 Nubian Toponyms in Medieval Nubian Sources Richard Pierce [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/djns Recommended Citation Pierce, Richard (2017) "Nubian Toponyms in Medieval Nubian Sources," Dotawo: A Journal of Nubian Studies: Vol. 4 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/djns/vol4/iss1/6 This item has been accepted for inclusion in DigitalCommons@Fairfield by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Fairfield. It is brought to you by DigitalCommons@Fairfield with permission from the rights- holder(s) and is protected by copyright and/or related rights. You are free to use this item in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses, you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 35 Nubian Toponyms in Medieval Nubian Sources Richard Holton Pierce Place names are meaningful. In discourse, they function as lexical pointers to extra-linguistic entities and in context can call to mind or even bring into being conceptual landscapes. In itself the etymol- ogy of a toponym may tell something about the place it refers to: what sort of place it is (green, arid), what happens there (bordel or house of prayer), or who named it (Nubian or Meroite). The same is to be expected of toponyms in Old Nubian, but with the strong limitation that they are removed from whatever oral so- cial context once gave rise to them and are only found embalmed in written sources. -

Égypte\/Monde Arabe, 27-28

Égypte/Monde arabe 27-28 | 1996 Les langues en Égypte Old Nubian and Language Uses in Nubia Mokhtar Khalil et Catherine Miller Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ema/1032 DOI : 10.4000/ema.1032 ISSN : 2090-7273 Éditeur CEDEJ - Centre d’études et de documentation économiques juridiques et sociales Édition imprimée Date de publication : 31 décembre 1996 Pagination : 67-76 ISSN : 1110-5097 Référence électronique Mokhtar Khalil et Catherine Miller, « Old Nubian and Language Uses in Nubia », Égypte/Monde arabe [En ligne], Première série, Les langues en Égypte, mis en ligne le 08 juillet 2008, consulté le 30 avril 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ema/1032 ; DOI : 10.4000/ema.1032 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 30 avril 2019. © Tous droits réservés Old Nubian and Language Uses in Nubia 1 Old Nubian and Language Uses in Nubia Mokhtar Khalil et Catherine Miller 1 The geographical boundaries of modem Nubia extend from the 1st cataract (Dabôd village) in Egypt to Ad-Dabba between the 3rd and 4th cataracts in Sudan. After the construction of the High Dam in Aswan in 1964, a large part of Nubia has been flooded and the Nubians have been relocated around Kom Ombo in Egypt and around Halfa el Jadida in Eastern Sudan (Kassala State}. In Antiquity and Medieval times, Nubia used to extend further to Soba (South of KhartoLim in Sudan). The human settlement of Nubia goes back very far in prehistoric time (4th millenium BC) and the history of the area is well attested throughout the Pharaonic period, where Nubia and Egypt had a long and quite complicated relationship: at some periods, Nubia was independent and developed powerful kingdoms (cf.