N3871R Proposal to Encode the Sindhi Script in ISO/IEC 10646

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Origins, Evolution and Decline of the Khojki Script

The origins, evolution and decline of the Khojki script Juan Bruce The origins, evolution and decline of the Khojki script Juan Bruce Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in Typeface Design, University of Reading, 2015. 5 Abstract The Khojki script is an Indian script whose origins are in Sindh (now southern Pakistan), a region that has witnessed the conflict between Islam and Hinduism for more than 1,200 years. After the gradual occupation of the region by Muslims from the 8th century onwards, the region underwent significant cultural changes. This dissertation reviews the history of the script and the different uses that it took on among the Khoja people since Muslim missionaries began their activities in Sindh communities in the 14th century. It questions the origins of the Khojas and exposes the impact that their transition from a Hindu merchant caste to a broader Muslim community had on the development of the script. During this process of transformation, a rich and complex creed, known as Satpanth, resulted from the blend of these cultures. The study also considers the roots of the Khojki writing system, especially the modernization that the script went through in order to suit more sophisticated means of expression. As a result, through recording the religious Satpanth literature, Khojki evolved and left behind its mercantile features, insufficient for this purpose. Through comparative analysis of printed Khojki texts, this dissertation examines the use of the script in Bombay at the beginning of the 20th century in the shape of Khoja Ismaili literature. -

WG2 M52 Minutes

ISO.IEC JTC 1/SC 2 N____ ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 N3603 2009-07-08 ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set (UCS) - ISO/IEC 10646 Secretariat: ANSI DOC TYPE: Meeting Minutes TITLE: Unconfirmed minutes of WG 2 meeting 54 Room S206/S209, Dublin Centre University, Dublin, Ireland 2009-04-20/24 SOURCE: V.S. Umamaheswaran, Recording Secretary, and Mike Ksar, Convener PROJECT: JTC 1.02.18 – ISO/IEC 10646 STATUS: SC 2/WG 2 participants are requested to review the attached unconfirmed minutes, act on appropriate noted action items, and to send any comments or corrections to the convener as soon as possible but no later than the Due Date below. ACTION ID: ACT DUE DATE: 2009-10-12 DISTRIBUTION: SC 2/WG 2 members and Liaison organizations MEDIUM: Acrobat PDF file NO. OF PAGES: 60 (including cover sheet) Michael Y. Ksar Convener – ISO/IEC/JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 22680 Alcalde Rd Phone: +1 408 255-1217 Cupertino, CA 95014 Email: [email protected] U.S.A. ISO International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set (UCS) ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2 N____ ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 N3603 2009-07-08 Title: Unconfirmed minutes of WG 2 meeting 54 Room S206/S209, Dublin Centre University, Dublin, Ireland; 2009-04-20/24 Source: V.S. Umamaheswaran ([email protected]), Recording Secretary Mike Ksar ([email protected]), Convener Action: WG 2 members and Liaison organizations Distribution: ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 members and liaison organizations 1 Opening Input document: 3573 2nd Call Meeting # 54 in Dublin; Mike Ksar; 2009-02-16 Mr. -

N3596 Proposal to Encode the Khojki Script in ISO/IEC 10646

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3596 L2/09-101 2009-03-25 Proposal to Encode the Khojki Script in ISO/IEC 10646 Anshuman Pandey University of Michigan Ann Arbor, Michigan, U.S.A. [email protected] March 25, 2009 Contents Proposal Summary Form i 1 Introduction 1 2 Background 1 3 Characters Proposed 5 3.1 Character Set . 5 3.2 Basis for Character Set and Glyph Shapes . 6 3.3 Characters Not Proposed . 8 4 The Writing System 10 4.1 General Features . 10 4.2 Inadequacies of the Script . 10 4.3 Supression of Inherent Vowel . 11 4.4 Consonant-Vowel Ligatures . 11 4.5 Consonant Conjuncts . 12 4.6 Nasalization . 13 4.7 Consonant Gemination . 13 4.8 Creation of New Characters . 13 4.9 Punctuation . 14 4.10 Abbreviations . 15 4.11 Number Forms and Unit Marks . 16 4.12 Variant Forms of Characters . 16 5 Implementation 16 5.1 Encoding Model . 16 5.2 Collation . 16 5.3 Character Properties . 17 5.4 Outstanding Issues . 18 6 References 19 List of Tables 1 Glyph chart for Khojki . 2 2 Names list for Khojki . 3 3 Transliteration of Khojki characters and Sindhi-Arabic analogues . 4 List of Figures 1 Inventory of Khojki vowel letters from Grierson (1905) . 20 2 Inventory of Khojki consonant letters from Grierson (1905) . 21 3 Inventory of Khojki consonant letters from Grierson (1905) . 22 4 Inventory of Khojki independent vowel letters from Asani (1992) . 23 5 Inventory of Khojki dependent vowel signs from Asani (1992) . 24 6 Inventory of Khojki consonants (b to dy) from Asani (1992) . -

KALĀM-E-MAWLĀ (Hindi – Gujarati Sayings of Hazrat Mawlana Ali A.S)

KALĀM-E-MAWLĀ (Hindi – Gujarati sayings of Hazrat Mawlana Ali A.S) With the introduction, annotation, transliteration, translation and approximated Arabic sayings and Quranic verses By Dr. Amin Valliani, ITREB (Pakistan), Karachi. 1 Ever-Blessing Words From the very beginnings of Islam, the search for knowledge has been central to our cultures. I think of the words of Hazrat Ali ibn Abi Talib, the first hereditary Imam of the Shia Muslims, and the last of the four rightly-guided Caliphs after the passing away of the Prophet (may peace be upon Him). In his teachings, Hazrat Ali emphasized that “No honour is like knowledge.” And then he added that “No belief is like modesty and patience, no attainment is like humility, no power is like forbearance, and no support is more reliable than consultation.” Notice that the virtues endorsed by Hazrat Ali are qualities which subordinate the self and emphasize others ---modesty, patience, humility, forbearance and consultation. What he thus is telling us, is that we find knowledge best by admitting first what it is we do not know, and by opening our minds to what others can teach us. Mawlana Hazar Imam, Address at the Commencement Ceremony of the American University in Cairo, dated 15th June, 2006. 2 This book is a humble tribute to my late teacher Itmadi Noor Din H.Bakhsh (d.2000) who inspired me to undertake this research based academic exercise. 3 Acknowledgments Upon completion of this project on Kālām-e-Mawlā, I bow my head and heart to thank the He, who made me able to undertake the academic task. -

Typographic Development of the Khojki Script and Printing Affairs at the Turn of the 19Th Century in Bombay by Juan Bruce

Typographic development of the Khojki script and printing affairs at the turn of the 19th century in Bombay by Juan Bruce Khōjā Studies Conference, cnrs-ceias, París, December 2016. Paper based on the dissertation The origins, evolution and decline of the Khojki script submitted in September of 2015 by the same author as part of the requirements of the Master of Arts in Typeface Design at the University of Reading, uk. overview The Khojki script is an Indian script whose origins are in Sindh (now south of Pakistan), a region that has witnessed more than 1,200 years of interplay between Islam and Hinduism. After the gradual occupation of the region by Muslims from the 8th century onwards, the script took on different usages among its community, the Khojas. Sindh, Punjab and Gujarat, were the first places that received gradual Muslim religious incursions into Hindu communities, to which language and writing constituted the first barrier for conversion. It is believed that one prominent Muslim pir (Pir Sadruddin) was very much active inside the Hindu Lohana community in the 14th century, a caste of merchants and traders. As a way to approach and transmit the teachings to the people, the pir adopted the Lohānākī script of this community. Later on, the converted came to be known as the Khoja caste. Significantly, a totally different creed, known as Satpanth, grew inside the community after the blend of these cultures. Academic interest has been stimulated by the special nature of the Satpanthi literature and its place in the Indian subcontinent. It has emerged as a fascinating example of an Islamic religious movement expressing itself within a local Indian religious culture. -

General Historical and Analytical / Writing Systems: Recent Script

9 Writing systems Edited by Elena Bashir 9,1. Introduction By Elena Bashir The relations between spoken language and the visual symbols (graphemes) used to represent it are complex. Orthographies can be thought of as situated on a con- tinuum from “deep” — systems in which there is not a one-to-one correspondence between the sounds of the language and its graphemes — to “shallow” — systems in which the relationship between sounds and graphemes is regular and trans- parent (see Roberts & Joyce 2012 for a recent discussion). In orthographies for Indo-Aryan and Iranian languages based on the Arabic script and writing system, the retention of historical spellings for words of Arabic or Persian origin increases the orthographic depth of these systems. Decisions on how to write a language always carry historical, cultural, and political meaning. Debates about orthography usually focus on such issues rather than on linguistic analysis; this can be seen in Pakistan, for example, in discussions regarding orthography for Kalasha, Wakhi, or Balti, and in Afghanistan regarding Wakhi or Pashai. Questions of orthography are intertwined with language ideology, language planning activities, and goals like literacy or standardization. Woolard 1998, Brandt 2014, and Sebba 2007 are valuable treatments of such issues. In Section 9.2, Stefan Baums discusses the historical development and general characteristics of the (non Perso-Arabic) writing systems used for South Asian languages, and his Section 9.3 deals with recent research on alphasyllabic writing systems, script-related literacy and language-learning studies, representation of South Asian languages in Unicode, and recent debates about the Indus Valley inscriptions. -

Khojki Script in ISO/IEC 10646

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3978 L2/11-021 2011-01-28 Final Proposal to Encode the Khojki Script in ISO/IEC 10646 Anshuman Pandey Department of History University of Michigan Ann Arbor, Michigan, U.S.A. [email protected] January 28, 2011 1 Introduction This is a proposal to encode the Khojki script in the Universal Character Set (ISO/IEC 10646). It replaces the following documents: • L2/08-201: “Towards an Encoding for the Khojki Script in ISO/IEC 10646” • N3596 L2/09-101 “Proposal to Encode the Khojki Script in ISO/IEC 10646” • N3883 L2/10-326 “Revised Proposal to Encode the Khojki Script in ISO/IEC 10646” This document is a revision of N3883 L2/10-326. Major changes from the previous proposal include the removal of some vowel and consonant letters, the reassignment of glyphs for some consonant letters, revision of the code chart, and the inclusion of new specimens. The ISO proposal summary form is enclosed. 2 Overview Khojki is a writing system used by the Nizari Ismaili community of South Asia for recording religious literature. It was developed in Sindh, now in Pakistan, for representing the Sindhi language. The script spread to surrounding regions and was used for writing Gujarati, Punjabi, and Siraiki, as well as several languages allied with Hindi. It was also used for writing Arabic and Persian. The name ‘Khojki’ (ሉሲሐ ,k̲ h̲ wājah “master خواجه khojakī, Devanagari खोजक khojakī) is derived from the Persian honorific title lord”. It is a translation of the Sanskrit ठाकुर ṭhākura, which was used as a title of address by the Lohānạ̄ community, who were were among the early Hindu converts to the Nizari Ismaili tradition in South Asia.1 Khojki is a Brahmi-based script of the Sindhi branch of the Landa family, which is a class of mercantile scripts related to Sharada.2 It is considered to be a refined version of the Lohānākị̄ script that was developed as a liturgical script for recording Ismaili literature. -

List of Ancient Indian Scripts - GK Notes for SSC & Banking

List of Ancient Indian Scripts - GK Notes for SSC & Banking India is known for its culture, heritage, and history. One of the treasures of India is its ancient scripts. There are a huge number of scripts in India, many of these scripts have not been deciphered yet. Most Indian languages are written in Brahmi-derived scripts, such as Devanagari, Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Odia etc. Read this article to know about a List of Ancient Indian Scripts. Main Families of Indian Scripts All Indian scripts are known to be derived from Brahmi. There are three main families of Indian scripts: 1. Devanagari - This script is the basis of the languages of northern India and western India: Hindi, Gujarati, Bengali, Marathi, Panjabi, etc. 1 | P a g e 2. Dravidian - This script is the basis of Telugu, Kannada. 3. Grantha - This script is a subsection of the Dravidian languages such as Tamil and Malayalam, although it is not as important as the other two. Ancient Indian Scripts Given below are five ancient Indian scripts that have proven to be very important in the history of India - 1. Indus Script The Indus script is also known as the Harappan script. It uses a combination of symbols which were developed during the Indus Valley Civilization which started around 3500 and ended in 1900 BC. Although this script has not been deciphered yet, many have argued that this script is a predecessor to the Brahmi Script. 2. Brahmi Script Brahmi is a modern name for one of the oldest scripts in the Indian as well as Central Asian writing system. -

SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY Feature Extraction and Classification

Pertanika J. Sci. & Technol. 27 (4): 1649 - 1669 (2019) SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY Journal homepage: http://www.pertanika.upm.edu.my/ Review article Feature Extraction and Classification Techniques of MODI Script Character Recognition Solley Joseph1,2* and Jossy George1 1Department of Computer Science Christ (Deemed to be University), Bangalore, Karnataka, 560029 India 2Carmel College of Arts, Science and Commerce for Women, Goa, 403713 India ABSTRACT Machine simulation of human reading has caught the attention of computer science researchers since the introduction of digital computers. Character recognition is the process of recognizing either printed or handwritten text from document images and converting it into machine-readable form. Character recognition is successfully implemented for various foreign language scripts like English, Chinese and Latin. In the case of Indian language scripts, the character recognition process is comparatively difficult due to the complex nature of scripts. MODI script - an ancient Indian script, is the shorthand form for the Devanagari script in which Marathi was written. Though at present, the script is not used officially, it has historical importance. MODI character recognition is a very complex task due to its variations in the writing style of individuals, shape similarity of characters and the absence of word stopping symbol in documents. The advances in various machine learning techniques have greatly contributed to the success of various character recognition processes. The proposed work provides -

Towards an Encoding for the Khojki Script in ISO/IEC 10646

Towards an Encoding for the Khojki Script in ISO/IEC 10646 Anshuman Pandey University of Michigan Ann Arbor, Michigan, U.S.A. [email protected] May 5, 2008 Contents Proposal Summary Form i 1 Introduction 1 2 Request for Allocation 1 3 Justification for Encoding 1 4 Characters Proposed 3 5 Technical Features 4 5.1 Name ............................................ 4 5.2 Classification ................................... ....... 4 5.3 Allocation...................................... ...... 4 5.4 EncodingModel................................... ...... 4 5.5 CharacterProperties. .......... 4 6 Orthography 6 6.1 GeneralFeatures ................................. ....... 6 6.2 Vowels.......................................... .... 6 6.3 OtherSigns ...................................... ..... 7 6.4 Gemination ...................................... ..... 7 6.5 Nukta ........................................... ... 7 6.6 WordBoundaries .................................. ...... 7 6.7 SentenceBoundaries .............................. ........ 7 List of Tables 1 Preliminary glyph chart for the Khojki script. .................. 2 ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 PROPOSAL SUMMARY FORM TO ACCOMPANY SUBMISSIONS FOR ADDITIONS TO THE REPERTOIRE OF ISO/IEC 106461 Please fill all the sections A, B and C below. Please read Principles and Procedures Document (P & P) from http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/principles.html for guidelines and details before filling this form. Please ensure you are using the latest Form from http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/summaryform.html. See also http://www.dkuug.dk/JTC1/SC2/WG2/docs/roadmaps.html for latest Roadmaps. A. Administrative 1. Title: Towards an Encoding for the Khojki Script in ISO/IEC 10646 2. Requester’s name: Anshuman Pandey ([email protected]) 3. Requester type (Member Body/Liaison/Individual contribution): Individual contribution 4. Submission date: May 5, 2008 5. Requester’s reference (if applicable): N/A 6. -

ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 N3950 Date: 2011-02-19

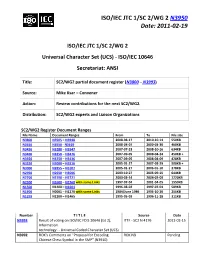

ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 N3950 Date: 2011-02-19 ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 2/WG 2 Universal Character Set (UCS) - ISO/IEC 10646 Secretariat: ANSI Title: SC2/WG2 partial document register (N3800 – N3993) Source: Mike Ksar – Convener Action: Review contributions for the next SC2/WG2. Distribution: SC2/WG2 experts and Liaison Organizations SC2/WG2 Register Document Ranges File Name Document Ranges From To File size N3800 N3505 – N3948 2008-08-17 2010-10-14 550KB N3550 N3550 - N3599 2008-04-07 2009-03-30 460KB N3450 N3288 – N3547 2007-07-23 2008-10-16 634KB N3400 N3250 – N3476 2007-09-05 2008-04-24 450KB + N3350 N3250 – N3436 2007-09-05 2008-04-09 428KB N3250 N3000 – N3316 2005-01-27 2007-08-29 508KB + N3000 N2855 – N3107 2005-01-27 2006-01-10 278KB N2950 N2650 – N3006 2003-10-27 2005-09-15 644KB N2700 N2190 – N2721 2003-03-14 2004-02-09 1220KB N2300 N1600 – N2360 with some Links 1997-07-04 2001-04-05 1550KB N1500 N1400 – N1604 1996-08-02 1997-07-04 589KB N1300 N0001 – N1270 with some Links 1984/June 1986 1995-10-20 255KB N1299 N1200 – N1465 1995-05-03 1996-11-28 311KB Number T I T L E Source Date N3993 Result of voting on ISO/IEC FDIS 10646 (Ed 2), ITTF - SC2 N 4176 2011-02-15 Information technology -- Universal Coded Character Set (UCS) N3992 ROK's Comments on “Proposal for Encoding ROK NB Pending Chinese Chess Symbol in the SMP” (N3910) N3991 Comments on Bassa Vah Comma Charles Riley 2011-02-14 N3990 Final Proposal to Encode Coptic Epact Numbers in Script Encoding Initiative 2011-02-14 ISO/IEC 10646 (SEI)- Anshuman Pandey N3989 Proposal to add ARABIC MARK SIDEWAYS NOON Lorna A. -

L2/10-012 2010-01-25

L2/10-012 2010-01-25 Title: Preliminary Proposal to Encode the Sindhi Script in ISO/IEC 10646 Source: Script Encoding Initiative (SEI) Author: Anshuman Pandey ([email protected]) Status: Liaison Contribution Action: For consideration by UTC Date: 2010-01-25 1 Introduction This is a proposal to encode the Sindhi script in the Universal Character Set (UCS). Sindhi is a sub-class of the Landa family of scripts, which is discussed in “A Roadmap for Scripts of the Landa Family” (L2/10-011). As recommended in L2/10-011, Sindhi should be encoded as an independent script. 2 Background Sindhi is a Brahmic script that belongs to the Landa family of scripts. It was used primarily throughout Sindh for writing Sindhi and other Indo-Aryan languages found in adjacent regions such as Gujarati. The writing system is known colloquially as ‘Baniyā̃’ or ‘Wānikọ̄ ’,1 which refer to the usage of the script by mercantile communities. There are several varieties of Sindhi, which are associated with regions within Sindh or par- ticular Sindhi communities. In Grammar of the Sindhi Language (1849), George Stack illustrated twelve local forms of Sindhi (Figure 3, Figure 4, and Figure 5). Several other local forms of Sindhi are presented in William Leitner’s “A Collection of Specimens of Commercial and Other Alphabets” (1882). Of these various regional scripts of Sindh, the Khudawadi and Khojki forms gained the most prominence. In 1868, an official committee of the Government of Bombay devised a standard script known as ‘Hindi Sindhi’ or ‘Hindu Sindhi’. The basis for this standardized script was the Khudawadi, or Khudabadi, form of Landa.2 The purpose of introducing a reformed Sindhi script was to standardize education and to develop a uniform medium for court records.